FBI Portland History

Early 1900s

The Portland Division has been open since the earliest years of the FBI. In August 1920, it was named one of nine divisional headquarters, and its special agent in charge, F.A. Watt, was placed in administrative charge of a number of other field offices in the Northwest. Except for a short period between 1930 and 1932 when the office was relocated to Seattle, the Portland Division has been in continuous service since the Bureau’s earliest years.

In its first decades, the Portland Division investigated a wide range of matters, such as anti-trust issues, prostitution cases, and subversion.

With the expansion of the federal criminal law, interstate automobile cases became an important responsibility for the Portland Division and the rest of the nation in the 1920s, and kidnapping came under the Bureau’s jurisdiction in 1932 when the federal Kidnapping Act was passed. Within a few years, the Portland Division played a key role in solving the 1935 kidnapping of nine-year old George Weyerhaeuser, the son of a wealthy Tacoma businessman. The crime gained nationwide notoriety, with Portland agents working diligently on the case until a ransom exchange led to the release of the young victim. When ransom money began to turn up in Salt Lake City, the Bureau’s Salt Lake Division and local police scoured the city and eventually arrested Margaret Waley for passing the money. Waley’s husband was arrested shortly after, and a third and final kidnapper was identified and later captured in 1936 by agents in San Francisco.

1940s

World War II led to a significant increase in the work and responsibility of the Portland Division. By 1942, the division was operating one of the FBI’s key radio stations, which not only maintained contact with FBI Headquarters and undercover agents in South and Central America, but also helped to intercept Japanese radio traffic in order to identify and thwart Japanese intelligence missions in South and Central America as well as on the West Coast of America. While the Portland Division continued handling its wide range of federal criminal matters, it also provided expert anti-sabotage advice and inspections at major manufacturing plants in the area, conducted numerous counterespionage investigations, and investigated a late-war Japanese campaign to send bomb-bearing balloons aloft to the United States. Given weather patterns, the few bombs that made it to U.S. soil landed in the Pacific Northwest.

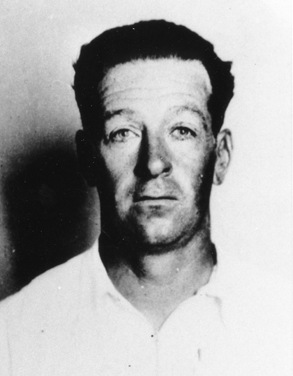

Special Agent in Charge F.A. Watt

Even before World War II was over, Portland agents began noticing an increase in Soviet espionage. At the end of the war, they began to reprioritize their counterintelligence work and concentrate on the activities of Soviet spies and the Communist Political Association (the U.S. Communist Party’s name at the time) and its connections to Soviet intelligence. Despite this intense focus on national security, interstate transportation of stolen motor vehicles, violations of the Selective Service Act, anti-trust matters, and many other violations were of significant concern to Portland in the post-war period.

By 1948, the Portland Division’s office was located in the U.S. Courthouse. In 1951, the division was maintaining satellite offices, or resident agencies, in Pendleton, Grants Pass, Salem, Eugene, and Klamath Falls. Most of these smaller offices were actually operated out of agents’ homes, but soon these home offices began sharing space in U.S. Postal Service facilities before eventually moving into separate offices. As time passed, some new resident agencies opened and others closed, including offices in Astoria, The Dalles, Coos Bay, Ontario, and Medford, to meet fluctuating investigative demands. Today, the division has five resident agencies—Bend, Eugene, Medford, Pendleton, and Salem.

Thomas James Holden

1950s and 1960s

With the 1950 launch of the FBI’s Ten Most Wanted Fugitives program, Portland gained a new ally in its criminal work—the American people. Three of the first ten of the Most Wanted Fugitives had Portland connections. Thomas James Holden, number one on the list, was a career criminal who was sought for a triple homicide. Agents of the Portland Division caught him on June 23, 1951 near Beaverton, Oregon. In total, 11 Top Ten fugitives were either from Oregon or were caught in Oregon. Of the original Top Ten fugitives, the Portland Division played a significant role in tracking down Thomas James Holden, Omar August Pinson, and Orba Elmer Jackson.

In October 1962, a hurricane hit Portland, killing 17 and injuring more than 100 people. Bureau personnel responded immediately, supporting the larger efforts of the leaders of the city and the state of Oregon.

At the same time, the political and cultural changes of that era created new challenges for the division. In 1969, for instance, Portland personnel were called upon to investigate a series of bombings in Eugene, Oregon. Similar violent extremist investigations became a key part of the division’s work in the latter half of the decade.

1970s

In 1971, the Portland office moved to its current location in the Crown Plaza Office Building at SW 1st and Clay. At this time, the division handled an average annual workload of 1,446 criminal cases, 832 security cases, and 84 applicant/other cases. The division had grown to 60 agents and 36 support employees.

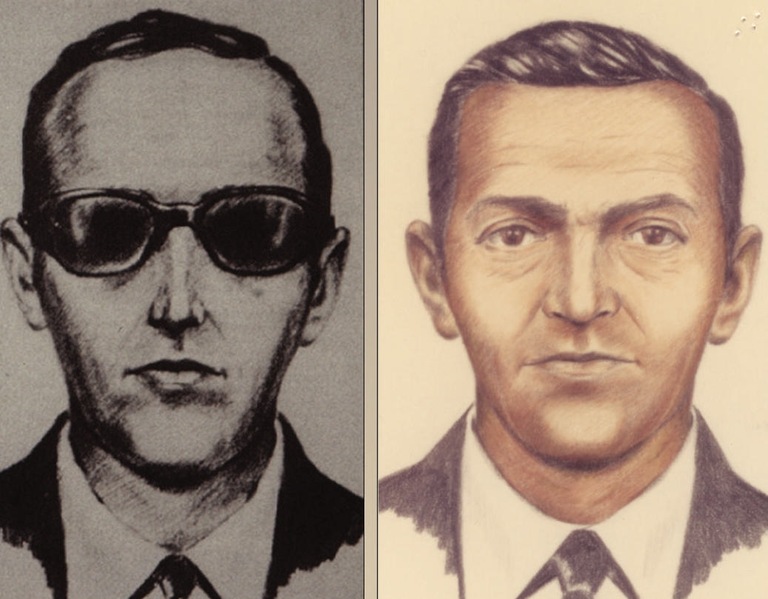

Portland continued to receive interesting cases, most of which it solved. One interesting matter that remains open is the so-called D.B. Cooper hijacking case. On November 24, 1971, a man calling himself Dan Cooper hijacked Northwest Orient Airlines Flight 727 as it left Portland International Airport. Mistakenly identified as D.B. Cooper, the man eventually jumped out over Southwest Washington with $200,000 in cash and a parachute. Although some of the money was recovered in 1980 along the Columbia River, Cooper’s disappearance remains a mystery.

In 1974, the Portland Division handled an extortion case involving the Bonneville Power Administration (BPA). That year, the FBI and BPA started receiving threatening letters stating that if the latter didn’t pay a $1 million ransom, a man by the name of “J. Hawker” would knock out power to Portland and set fire to the watershed that provided drinking water to the area. On October 4, 1974, explosions at three power transmission towers near Maupin did extensive damage. A few weeks later, three more damaged towers were found in both Brightwood and Parkdale, and two more damaged towers were found in the Bull Run Reservoir. Despite the bomber’s use of a complicated communications system in his demands—including citizen’s band (CB) radios, morse code, and duck calls—the FBI tracked him down. Agents arrested David Heesch and his wife, Sheila Heesch (who was also involved), of Beavercreek, Oregon, on November 8, 1974. A judge sentenced David Heesch to 20 years in prison and Sheila Heesch to 14 months.

Portland continued to contribute to other significant Bureau investigations. In June 1975, Minneapolis Division agents Jack R. Coler and Ronald A. Williams were killed in a shootout with members of a violent radical group called the American Indian Movement, or AIM. A short time later, an Oregon State Police trooper attempted to stop two of AIM’s leaders—Dennis Banks and Leonard Peltier—as they were driving down Interstate 84. The men were in a vehicle leading a small caravan, including a motor home owned by actor Marlon Brando. During a shootout with the state trooper, Banks and Peltier escaped. The Portland Division conducted the investigation and developed key evidence against the two men. One of the murdered agents’ weapons was found in the roadway, and Peltier’s bloody fingerprints were found in a building in eastern Oregon that he stopped at following the shootout. Dynamite, timing devices, ammunition, and weapons were found in the vehicles. After a 10-year legal battle—including an appeal to the U.S. Supreme Court—Banks pled guilty to weapons and explosives charges. Peltier, who had fled to Canada, was eventually captured and convicted in the murder of the agents.

Sketches of D.B. Cooper

Starting in 1979, a violent gang of criminals committed a string of bank robberies and other crimes tied to a heroin trafficking ring in Oregon. Stephen Michael Kessler led the distribution ring. After a federal grand jury indicted him in 1982 for these crimes, Kessler was sent to the Rocky Butte Jail in Portland. On July 25, 1982, Kessler and five others escaped from Rocky Butte using a small .22 caliber revolver that had been smuggled inside. A 61-year-old guard, Irv Burkett, was shot and permanently disabled during the escape. (Rocky Butte has since been torn down.) Kessler was captured a few weeks later in Missouri. Eventually, dozens of people faced charges due to their involvement with the Kessler gang crimes and/or the escape. There were more than 40 federal convictions (three-quarters of those in FBI cases) and more than 15 state convictions.

1980s and 1990s

Violent crime continued to be a concern of Portland into the 1980s. In January 1983, a 20-year-old Washington man, Glen Kurt Tripp, boarded a Northwest Orient jetliner and demanded that he be flown to Afghanistan. He falsely asserted that he had a bomb in a box he was carrying. After a three-hour standoff, two Portland FBI agents snuck on board. One shot and killed Tripp to prevent him from harming the 35 passengers and six crew members.

In the early 1980s, a man by the name of Robert Mathews founded “The Order,” a supremacist group intent on creating a “White American Bastion” in the Pacific Northwest. The group turned to violent criminal activity to fund its work—including robbing banks and armored cars. Its members also were implicated in the murder of a controversial talk radio host. In 1984, while investigating Mathews and his group for their various crimes, agents from Portland were fired upon at the Capri Motel in northeast Portland; a shootout ensued. One agent was wounded, but Mathews escaped. He was killed a few weeks later during a raid at a cabin on Whidbey Island, Washington. Eventually, dozens of members of The Order were tried and convicted on charges ranging from counterfeiting and conspiracy to racketeering and robbery.

The year 1984 also brought the first modern bio-terror attack on U.S. soil, and it happened in Oregon. The Rajneeshees, a cult dedicated to the Bagwan Shree Rajneesh, lived in a commune near the town of Antelope, Oregon. The group spread salmonella bacteria over salad bars at restaurants in The Dalles, a city in Wasco County, Oregon. They were testing a plan to make enough people sick so that they could influence the vote for the county commissioner position later that year. Although more than 750 people fell ill during the test run, the group did not follow through with another attack near election day. Initially, health officials thought the outbreak was the result of unsanitary conditions at the restaurants. But, in 1985, when the Bhagwan Rajneesh announced that some of his followers were responsible, a joint Oregon State Police and Portland Division investigation turned up salmonella samples and other evidence at the commune. It also uncovered plans to kill then-U.S. Attorney Charles Turner. Two cult officials were convicted for their role in planning and implementing the bio-poisoning.

The Portland Division also became involved in the growing national savings and loan crisis at its onset. In December 1985, the State Federal Savings and Loan in Corvallis, Oregon collapsed, due mostly to fraud; the losses topped $150 million. The Portland Division was called in to investigate a variety of potential crimes. One of the most prevalent frauds was the use of “straw borrowers”—people who borrowed money not for themselves, but for others. While the defendants argued that they were just trying to help the S&L by increasing its loan portfolio, three different juries disagreed. The first case went to trial in 1989. In the end, four people pled guilty and four more were convicted.

Some crimes touched even closer to home. In May 1987, a man entered the Portland Division building with a loaded 9 mm pistol and a box of ammunition. He held five unarmed agents hostage, refused to talk to negotiators, and said that if anyone came in, he would start shooting. When rescuing agents entered the room, the man fired on them, but was shot and killed. No FBI employees were hurt.

In 1982, the FBI gained concurrent jurisdiction with the Drug Enforcement Agency (now the Drug Enforcement Administration) over federal drug violations. Given its location as a coastal state, drug trafficking was a serious concern to all Oregon law enforcement and especially the Portland Division. The late 1980s and early 1990s brought a number of high-profile drug cases to the Portland Division. In 1988, for example, Operation Forceout resulted in the seizure of 22 kilos of cocaine, 1.5 pounds of tar heroin, and about $1.5 million worth of real estate and personal property. A trafficking ring had been responsible for moving about 50 kilos of cocaine between Los Angeles and Portland each month. Another case—Operation Tarport—grew out of Forceout and targeted continuing drug activity. It led to 31 federal narcotics convictions, including a 20-year sentence for the group’s leader. Prosecutors said that the ring had sold more than $50 million worth of cocaine and heroin in 1988 and 1989. And in September 1991, more than 200 federal agents and local officers arrested 28 people as part of Operation Sintrak. During this year-long investigation, seven undercover agents bought large quantities of drugs from members of the ring on more than 100 occasions.

Another Portland Division case pushed the office into the national spotlight. On January 6, 1994, a male attacker clubbed figure skater Nancy Kerrigan in the knee during the U.S. Figure Skating Championships. He was quickly linked to Kerrigan’s fierce competitor Tonya Harding, and because of where Harding lived and trained, it was the responsibility of Portland Division to interview her about the crime. On January 18, 1994, national media satellite trucks gathered as Harding met with FBI agents in Portland for more than 10 hours as part of the investigation. A few months later, she pled guilty to hindering the investigation and was sentenced to probation and community service. Three others served jail time.

On May 29, 1996, Kathleen McChesney was appointed special agent in charge of the Portland Division. She was the first female appointed to head the division and the second woman to achieve that rank in Bureau. After her time in Portland, she continued to advance, becoming the highest-ranking woman in FBI history when she was appointed to the position of executive assistant director for Law Enforcement Services in December 2001.

Post-9/11

Christian Longo

The attacks of September 11 immediately made preventing terrorist attacks the top priority of the FBI and the Portland Division. In response, Portland worked diligently to expand its intelligence capabilities, to improve cooperation and coordination with other law enforcement agencies in its jurisdiction (especially through its Joint Terrorism Task Forces), and to re-allocate its resources to address a changed and changing series of threats.

Criminal investigative work continued to be a key focus of the Portland Division. During the 2001 holiday season, for example, Christian Longo murdered his wife and three children, placed their bodies in suitcases, and dumped them in the bay at Newport, Oregon. He fled the country, and Oregon law enforcement quickly linked him to the violent murders. On January 11, 2002, the Portland office announced that the FBI was adding Longo to its Ten Most Wanted Fugitives list. Thanks in part to the media coverage, Longo was quickly tracked down in Mexico and taken into custody. He was back in the U.S. by January 14, 2002 and ultimately convicted and sentenced to death for his family’s murder.

Another example of the Portland Division’s work was in the January 2002 disappearance of Ashley Pond. The young girl had disappeared on her way to school in Oregon City. In March 2002, the same thing happened to her classmate, Miranda Gaddis. The Portland Division and other Oregon law enforcement agencies conducted an exhaustive eight-month search for the girls and their abductor that led them to the property of Ward Weaver, a neighbor of the two. Portland Division personnel and Oregon City Police recovered both girls’ bodies, and Weaver eventually pled guilty. The horrible crime gained international attention.

Counterterrorism, though, has remained Portland’s top charge. Because of Oregon’s key role in international commerce and U.S. border security, the division has conducted numerous investigations into potential terrorist threats. One of the most serious involved a group of Americans who sought to join international terrorists in attacking the United States. On October 3, 2002, following an extensive Portland Division investigation later dubbed the “Portland Seven” case, a federal grand jury indicted five men with Portland ties—Jeffrey Leon Battle, Patrice Lumumba Ford, Ahmed Bilal, Muhammad Bilal, and Habis al Saoub—on charges that they planned to travel to Afghanistan to wage war against U.S. troops. Also indicted was a Portland woman, October Lewis, on money laundering charges related to the conspiracy. In March 2002, a seventh subject, Maher Hawash, was picked up as material witness and then later charged in the case following a more detailed investigation of his connections to the other six. All pled guilty except for al Saoub, who was killed fighting along the Pakistani-Afghani border.

The Portland Division has also worked domestic terrorism cases. In January 2006, a federal grand jury indicted 11 people as part of Operation Backfire, a nine-year FBI investigation into nearly 20 crimes committed by eco-terrorists across the western United States. The crimes, mostly arsons, caused tens of millions of dollars in damage. As the months passed, more indictments and arrests followed. A total of 10 members of “The Family” pled guilty. One was convicted at trial, and four remain fugitives. The Portland Division played a crucial role in this multi-division investigation as several crimes occurred in its jurisdiction and a number of the terrorists involved were eventually found in the Portland area.

Another top priority since 9/11 has been preventing cyber crime. On September 9, 2005, the Portland Division and other Northwest law enforcement agencies took a large step in increasing their collective ability to deal with this growing threat by opening the Northwest Regional Computer Forensic Laboratory, or RCFL. The Northwest RCFL, which is run by a board of directors made up of local participating law enforcement agencies, processes all kinds of digital evidence from law enforcement agencies throughout Oregon and Southwest Washington.

On July 25, 2008, to coincide with the Bureau’s 100th anniversary, the Portland Division celebrated the grand opening of a new regional training facility in Columbia County. With its strong tradition of investigative success, the Portland Division looks forward to the next century as it continues to serve the people of Oregon and the wider population of the United States.