World War, Cold War, 1939-1953

Heading into the late 1930s, fresh off a victory over the gun-slinging gangsters, the FBI hardly had time to catch its collective breath.

The Bureau had reformed itself on the fly; it was stronger and more capable than ever. But now, with the world rushing headlong into war and the pendulum swinging back towards national security concerns, the FBI would need to refocus and retool its operations once again.

At the start of the decade, the public enemies were almost entirely homegrown—from “Scarface” to “Baby Face.” The next wave of villains would come primarily from afar, and they were in many respects bigger and badder still. They were hyper-aggressive fascist dictators, fanatical militarists, and revolution-exporting communists—along with their legions of spies, saboteurs, and subversive agents—who sought to invade, infiltrate, or even conquer entire swaths of territory, if not the world. They threatened not only the fate of peoples and nations, but the survival of democracy itself.

Across the Atlantic in Europe, 1939 was a dark turning point. Five years earlier, less than a month after a cornered Dillinger had reached for his gun the last time, a power-hungry Adolph Hitler had declared himself “Führer” and taken total control of Germany. Hitler wasted little time rearming the country. He meant to build an empire—the Third Reich—and within a few years he’d annexed Austria and the Sudetenland, a German-speaking region in Czechoslovakia. England and France, hoping to cut their losses through appeasement, acceded to the takeovers. But in 1939, Hitler seized the rest of the Czechoslovakia and invaded Poland. England and France had seen enough and declared war.

Dueling dictators: Hitler and Mussolini in 1940. AP Photo.

Dark days: A mass roll call of Nazi troops in Nuremberg, November 9, 1935. National Archives.

In the Far East, Japan was making military waves as well. It invaded China in 1937, seized its northern capital, began taking control of coastal areas and nearby islands dotting the Pacific, and even deliberately sank an American gunboat. It formally joined with Germany and Mussolini’s Italy to form the Axis powers in September 1940.

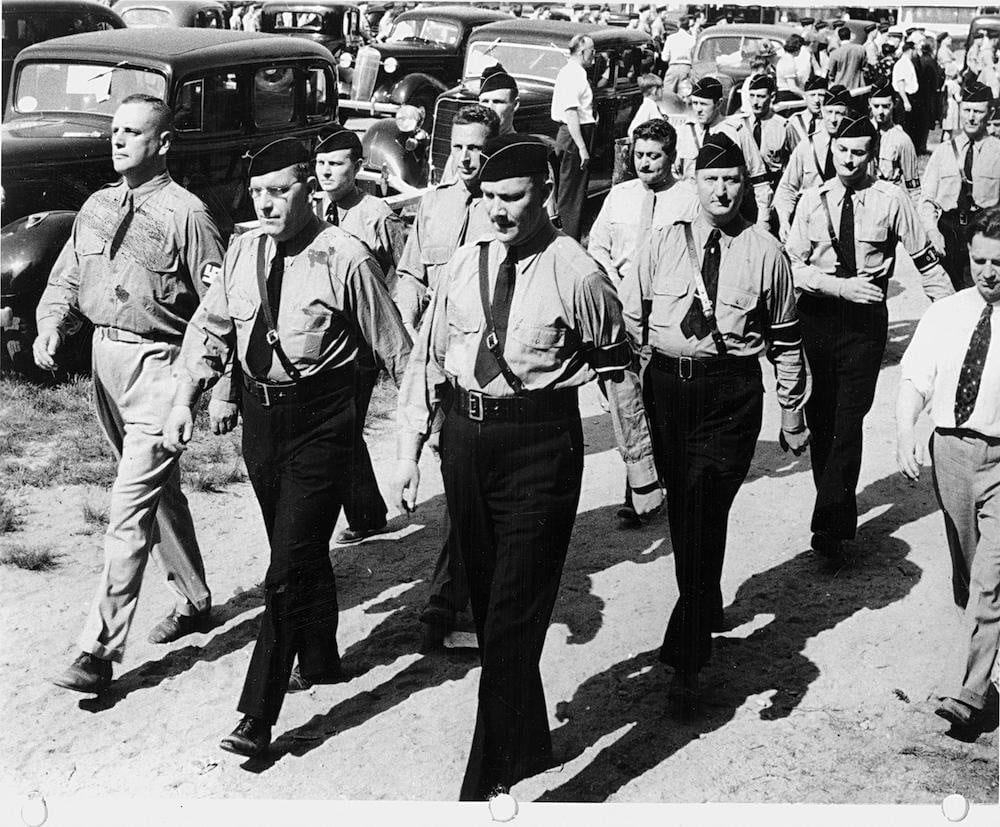

Cushioned by twin oceans, an isolationist America was staying out of the fray—for the time being. But, remembering how helpless it was against German sabotage in the years leading up to World War I, the nation wasn’t taking any chances at home. The lingering Great Depression provided fertile ground for fascism. Groups like the German American Bund and the Silver Shirts that embraced the Nazi vision were becoming more and more vocal. And Americans were increasingly becoming enamored of communism and its seductive promise of a classless state; the Communist Party of the United States and other like-minded organizations soon boasted more than a million members.

President Roosevelt was concerned—he suspected these groups were allying themselves to foreign political movements seeking to overturn democracy and were crossing the line into criminal activity. In 1934, he had first asked the FBI to determine if American Nazi groups were working with foreign agents. In 1936, the President and Secretary of State tasked the Bureau with gathering intelligence on the potential threats to national security posed by fascist and communist groups.

Members of the German American Bund parade through the streets of New York in the 1940s. Anastase Vonsiatsky on the far left pled guilty to espionage in 1942.

Meanwhile, Nazi espionage on U.S. soil had become a real threat. The intelligence arms of the Army and Navy had noticed increased activity by German and Japanese spies in the late 1930s and began working with the Bureau to disrupt it. Learning the counterintelligence ropes as it went along, the FBI was ultimately given the lead in these cases and uncovered some 50 spies operating in America before the nation entered the war, including a massive ring led by long-time German agent Fritz Duquesne.

As the new decade opened, the nation was drifting towards war and increasingly supporting the Allied cause. It clearly needed more and better intelligence to understand the threats posed by the Axis powers. The Bureau had been put in charge of domestic intelligence and had already built an extensive network of sources, with law enforcement around the country serving as an important set of eyes and ears. It had also begun developing connections abroad with Canadian and British intelligence and law enforcement.

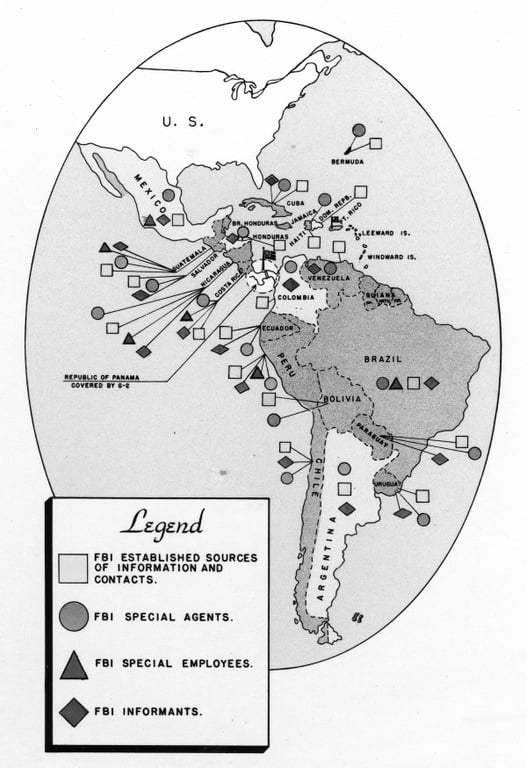

But who would handle overseas intelligence? There was no CIA in 1940—and its predecessor, the Office of Strategic Services, would not be launched until June 1942. Roosevelt decided to assign intelligence responsibilities for different parts of the globe to various agencies. The Bureau landed the area closest to home—the Western Hemisphere.

The Special Intelligence Service

| ||||

| ||||

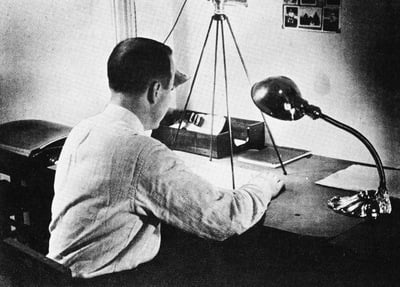

Top: An FBI agent in Brazil uses a desktop lab to photograph |

Who was the “golfer” who easily won a local championship overseas and went on to become personal friends with the country’s political leaders?

Who was the “traveling companion” of a South American police official—an official who boasted that he “could spot any FBI undercover man on sight”?

Who was the “visitor” to a foreign country who drew up legislation that improved that nation’s ability to protect itself against Axis intelligence activities?

They were all FBI agents, working undercover in Central and South America during World War II as part of the Bureau’s “Special Intelligence Service,” established in 1940 as a response to an order of President Roosevelt.

It was a vital mission. By 1940, South America had become a hotbed of German intrigue. More than half-a-million German emigrants—many supporters of the Third Reich—had settled in Brazil and Argentina alone. In line with the Bureau’s earlier intelligence work on threats posed by Germany, Roosevelt wanted to keep an eye on Nazi activities in our neighbors to the south. And when the U.S. joined the Allied cause in 1941, the President wanted to protect the nation from Hitler’s spies and collect intelligence on Axis activities to help win the war.

Over the next seven years, the FBI sent more than 340 agents and support professionals undercover into Central and South America as part of the Special Intelligence Service.

There was a significant learning curve—it took some time for the FBI to get undercover operatives in place and to master the languages. But within months, the Special Intelligence Service was working well. The service was gathering information and sending it back to FBI Headquarters in Washington, where it was crafted into useful intelligence for the military and others. And overseas, it developed ways of sharing crucial information with law enforcement and intelligence services there so they could round up Axis spies and saboteurs.

How successful was the Special Intelligence Service? The numbers speak for themselves. By 1946, it had identified 887 Axis spies, 281 propaganda agents, 222 agents smuggling strategic war materials, 30 saboteurs, and 97 other agents. It had located 24 secret Axis radio stations and confiscated 40 radio transmitters and 18 receiving sets. And the FBI had even used some of these radio networks to pass false and misleading information back to Nazi Germany.

The Special Intelligence Service was disbanded after the war, and the newly formed CIA was asked to take over its operations and expand U.S. intelligence activities worldwide. But the intelligence operation served the nation well: it helped protect the homeland, provided valuable lessons in intelligence and undercover operations for the Bureau for years to come, and set the stage for the FBI’s overseas Legal Attaché program.

Masters of Disaster: In August 1940, the FBI created a “Disaster Squad” to help identify victims of airline crashes and other events. It’s gear are shown here.

Strategically, it made sense—South and Central America were fast becoming staging grounds for the Nazis to send spies into the U.S. and hubs for relaying information back to Germany. In one of the least well known success stories in Bureau history, the FBI responded to the President’s charge by setting up a Special Intelligence Service in June 1940 that sent scores of agents undercover to knock out the Axis spy nests. Around that time, it also started officially stationing agents as diplomatic liaisons in U.S. embassies—the forerunner of today’s Legal Attachés—to coordinate international leads arising from the Bureau’s work.

When war finally did come to America—with a bang at Pearl Harbor—the Bureau was ready. In fact, as the bombs fell, Honolulu Special Agent in Charge Robert Shivers was on the phone with FBI Headquarters and Director Hoover, who quickly implemented the war plans the FBI already had in place and put the organization on a 24/7 schedule.

The Case of the Treasonous Dolls

| ||||

| ||||

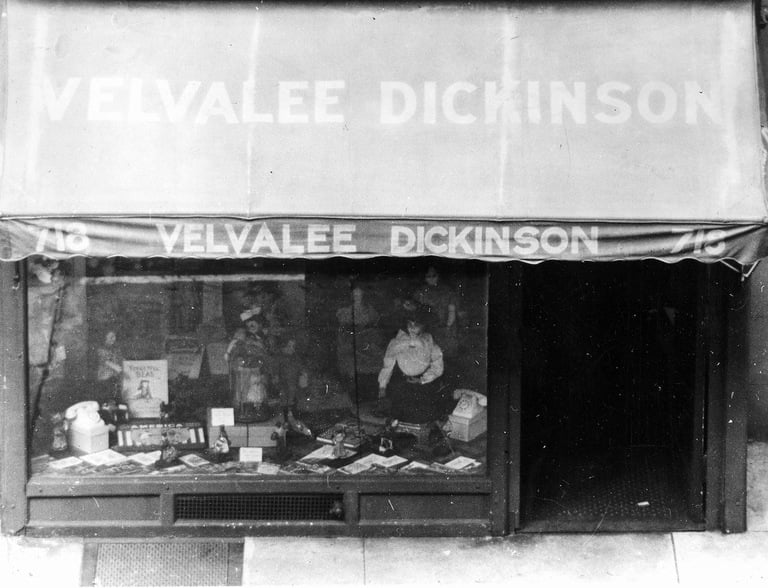

Above: Dickinson’s doll shop in New York City in 1937 and one of |

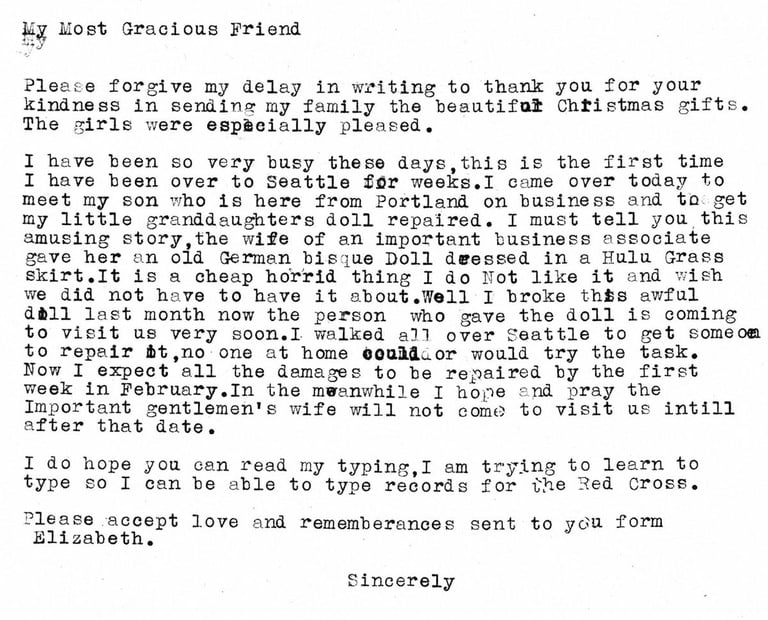

In early 1942, five letters were written and mailed by seemingly different people in different U.S. locations to the same person at an address in Buenos Aires, Argentina. Even more strangely, all of them bounced “Return to Sender”—and the “senders” on the return address (women in Oregon, Ohio, Colorado, and Washington state) knew nothing about the letters and had not sent them.

The FBI learned about all this when wartime censors intercepted one letter postmarked in Portland, Oregon, puzzled over its strange contents, and referred it to cryptographers at the FBI Laboratory. These experts concluded that the three “Old English dolls” left at “a wonderful doll hospital” for repairs might well mean three warships being repaired at a west coast naval shipyard; that “fish nets” meant submarine nets; and that “balloons” referred to defense installations.

The FBI immediately opened an investigation.

It was May 20, 1942, when a woman in Seattle turned over the crucial second letter. It said, “The wife of an important business associate gave her an old German bisque Doll dressed in a Hulu Grass skirt...I broke this awful doll...I walked all over Seattle to get someone to repair it....”

In short order, the FBI turned up the other letters. It determined that all five were using “doll code” to describe vital information about U.S. naval matters. All had forged signatures that had been made from authentic original signatures. All had typing characteristics that showed they were typed by the same person on different typewriters. How to put these clues together?

It was the woman in Colorado who provided the big break. She, like the other purported letter senders, was a doll collector, and she believed that a Madison Avenue doll shop owner, Mrs. Velvalee Dickinson, was responsible. She said Ms. Dickinson was angry with her because she’d been late paying for some dolls she’d ordered. That name was a match: the other women were also her customers.

Who was Velvalee Malvena Dickinson? Basically, a mystery. She was born in California and lived there until she moved with her husband to New York City in 1937. She opened a doll shop on Madison Avenue that same year, catering to wealthy doll collectors and hobbyists, but she struggled to keep it afloat. It also turned out that she had a long and close association with the Japanese diplomatic mission in the U.S.—and she had $13,000 in her safe deposit box traceable to Japanese sources.

Following her guilty plea on July 28, 1944, Ms. Dickinson detailed how she’d gathered intelligence at U.S. shipyards and how she’d used the code provided by Japanese Naval Attaché Ichiro Yokoyama to craft the letters. What we’ll never know is why the letters had been, thankfully, incorrectly addressed.

One important step the Bureau had taken in the run-up to war was to put together a list of German, Italian, and Japanese aliens in the U.S. who posed a clear threat to the country. Under presidential order issued on the evening of December 7, the Bureau moved to arrest these enemies and present them to immigration officials for hearings (represented by counsel) and for possible deportation. Within 72 hours, more than 3,800 aliens had been taken into custody without incident.

Remembering the civil rights lessons of the “Palmer Raids” in 1920, Hoover wanted nothing to do with the hysteria that called for rounding up Japanese-Americans on a much wider scale. He opposed that step, arguing that the Bureau had already moved against the real threats. But fear and prejudice prevailed, and in early 1942, some 120,000 Japanese—more than half U.S. citizens—were hastily detained and interred by the military under executive order.

The FBI Lab continued to grow in size and strength during the war.

For the FBI, life during wartime was incredibly busy. The Bureau had a vital role to play in protecting the homeland and supporting the war effort—from rounding up draft dodgers to investigating companies that deliberately supplied defective war materials just to turn a tidier profit. The FBI continued performing background checks on federal workers to keep criminals from entering the government. It kept working to head off espionage and stepped up its efforts to gather and analyze intelligence and to feed it to policymakers. The FBI Laboratory, growing stronger and more capable by the year, played a pioneering role by helping to break enemy codes and by engineering sophisticated intercepts.

An FBI agent unearths materials buried by the Nazi saboteurs in 1942.

The FBI was also in charge of preventing sabotage at home, and that meant running to ground every hint and rumor of potential attack. None of the reports the Bureau received and investigated—more than 20,000 in all—ultimately panned out; not a single act of enemy-directed sabotage was carried out on U.S. soil during the conflict. But that was hardly an accident. Before the country had entered the war, the FBI had surveyed more than 2,000 major industrial plants in the country and provided a series of suggestions on tightening their security, including lessons agents learned from the British.

That didn’t mean the Nazis didn’t try to attack the homeland directly. In June 1942, for example, German subs dropped off four saboteurs each in Long Island and northeastern Florida. The Nazis had trained these men in explosives, chemistry, and secret writing. But one of the men—George Dasch—got cold feet and turned himself in to the FBI in New York City. Agents quickly tracked down and arrested the remaining seven saboteurs before any harm was done.

The Mysterious Russian Letter

In the summer of 1943, an anonymous typewritten letter in Russian suddenly appeared at FBI Headquarters.

Talk about intrigue: the disgruntled writer accused more than ten Soviet diplomats in the U.S. of being spies, including the Soviet Vice-Consuls in San Francisco and New York and the Second Secretary of the Soviet Embassy in Washington— Vasilli Zubilin. The author even claimed (falsely) that Zubilin was spying for the Nazis.

Vasilli Zubilin. The author even claimed (falsely) that Zubilin was spying for the Nazis.

The charges were hard to believe. The Russians—our country’s allies in World War II—spying on the U.S.?

At the time, the FBI had only just begun investigating the extent of Soviet operations in America, with most resources heavily dedicated to Axis espionage and sabotage cases.

Now, this letter. What to make of it? Parts of it were strange and unbelievable, like the Nazi connections, but other parts confirmed things the FBI already knew or suspected. It was clear that its author was credible and well versed in Soviet intelligence in the United States.

Four months earlier, in fact, agents had learned that Zubilin had spoken with—and slipped money to—a Communist Party official named Steve Nelson. Zubilin’s aim? To infiltrate a Berkeley, California, lab doing work for the Manhattan Project, America’s secret atomic bomb program. The FBI passed what it learned about Zubilin’s spying to the War Department, which had primary investigative jurisdiction on the project. After the war ended, agents would investigate other, more serious attempts to steal U.S. A-bomb secrets, but that’s another story.

In the meantime, the Bureau had a predicate to take a closer look at Soviet espionage. Agents launched a major investigation to discover the potential interrelationships of Soviet diplomats, the Communist Party of the United States, and the Communist International party, or Comintern.

Through the case—called COMRAP, for “Comintern Apparatus”—the FBI learned that Soviet spying was a significant threat, which helped the Bureau prepare for the Cold War to come.

The Bureau’s domestic counterintelligence work continued full force as well, with plenty of successes. The FBI employed a variety of double agents to disrupt enemy espionage, set up radio networks to gather intelligence and spread disinformation, and used its growing scientific capabilities to track down spies like Velvalee Dickinson.

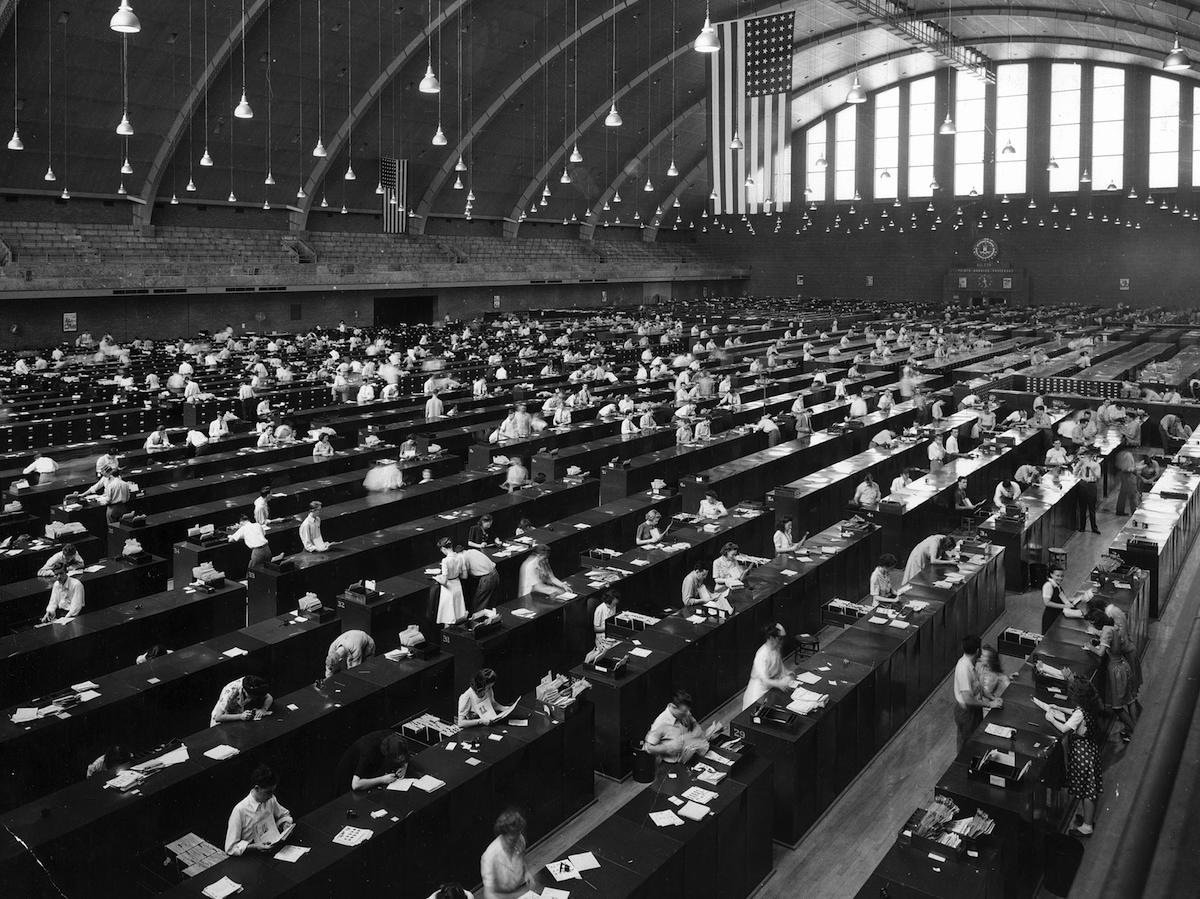

All of these new responsibilities required an influx of manpower—and Congress readily delivered the resources. The FBI’s rolls swelled from just 2,400 agents and support employees in 1940 to a war-time peak of more than 13,000 in 1944. Because of its National Academy training regimen for law enforcement executives, the Bureau had a ready pool of experienced graduates that it could tap into for new special agents. The FBI also brought on board huge numbers of professionals for its fingerprinting, scientific, and records management operations; its Identification Division grew so large that it had to be moved to a federal armory larger than a football field.

The FBI’s fingerprinting work grew so massive during the war that it had to be moved to a federal armory larger than a football field.

The nation breathed a sigh of relief when the Axis powers finally collapsed. Germany—with most of its troops captured and Berlin surrounded by advancing American and Soviet forces—was the first to raise the white flag, in May 1945. After being soundly defeated in the field and experiencing the horror of two A-bombs, Japan surrendered in August.

War was over. At least for the moment.

A more insidious, protracted conflict, it turns out, would soon be underway. The ambitious Soviets had snapped up several Eastern European countries as war prizes, and its “Iron Curtain” would soon descend, physically and symbolically dividing east and west, communism and democracy. The U.S. and Soviet Union—the two primary superpowers on the block—would spend the next four decades trying to gain the military and political upper hand. With both countries stockpiling nuclear weapons, the stakes were high.

The FBI’s growing national security capabilities would be crucial in the coming Cold War, but it quickly realized that it had a lot of catching up to do with the U.S.S.R. Although the Bureau had learned of Soviet espionage during World War II through its investigation of Russian diplomat and spy Vasili Zubilin and others, its war-time counterintelligence resources were overwhelmingly and understandably focused on the Axis threats. Our “allies” the Soviets, meanwhile, had used the war years to sneak agents into sensitive positions in our government. They had even subverted some of our nation’s policies and sought to influence our intelligence practices.

The defections of Soviet code clerk Igor Guzenko in the late summer of 1945 and U.S. citizen turned Soviet spy Elizabeth Bentley a few weeks later led to the FBI’s first major breaks in learning how much damage had been done to national security. In 1948, revelations on Soviet espionage triggered congressional hearings and front-page headlines when Time magazine editor Whittaker Chambers accused a prominent New Deal attorney named Alger Hiss of spying for the Russians; challenged by Hiss to prove his claims, Chambers produced solid evidence that Hiss had passed him classified information for the Soviets.

Carefully hollowed containers for transmitting microfilmed messages to Moscow.

Ultimately, the tide began turning. Using strong detective work and cutting-edge intelligence collection and analysis tools, the FBI and its partners in the intelligence community—along with allies in Canada and Great Britain—began dismantling Soviet spy networks. An Army Signal Corps project—later code-named Venona—helped this effort a great deal, providing the FBI with intelligence-rich telegrams sent from Soviet spies back to Moscow. Over the course of the project, which ran from 1943 until 1980, the FBI and its partners identified some 350 persons connected with Soviet intelligence. Venona was so sensitive that it was kept under wraps for some four decades; its information was not even used in court cases to keep from tipping off the Russians. The Bureau quietly used Venona intelligence, for example, to uncover an espionage ring run by Julius and Ethel Rosenberg that passed secrets on the atomic bomb to the Soviet Union.

By the early 1950s, the FBI and its allies had largely purged the federal government of dangerous moles and moved to become more proactive in infiltrating and deceiving Soviet intelligence. These successes forced the Soviets to retool their espionage efforts and begin relying on “illegal” agents—professional spies using various covers to hide in society at large. A good example was William Fisher (aka Rudolf Abel), who posed as a retired photographer while secretly recruiting and supervising Soviet spies. The FBI captured him in 1957.

The Bureau’s traditional criminal work, of course, continued during the early Cold War—from the Brinks robbery in 1950 to the kidnapping and murder of young Bobby Greenlease in 1953. The FBI also launched a key crime-fighting tool in March 1950—the “Ten Most Wanted Fugitives” list—which has since enlisted the help of a ubiquitous news media and a watchful public to capture more than 450 of the nation’s most dangerous criminals.

As the FBI headed into the middle of the decade, though, a rising criminal challenge based on an age-old problem—racial prejudice—would soon dominate the national stage and require the Bureau’s growing involvement.

The Black Dahlia

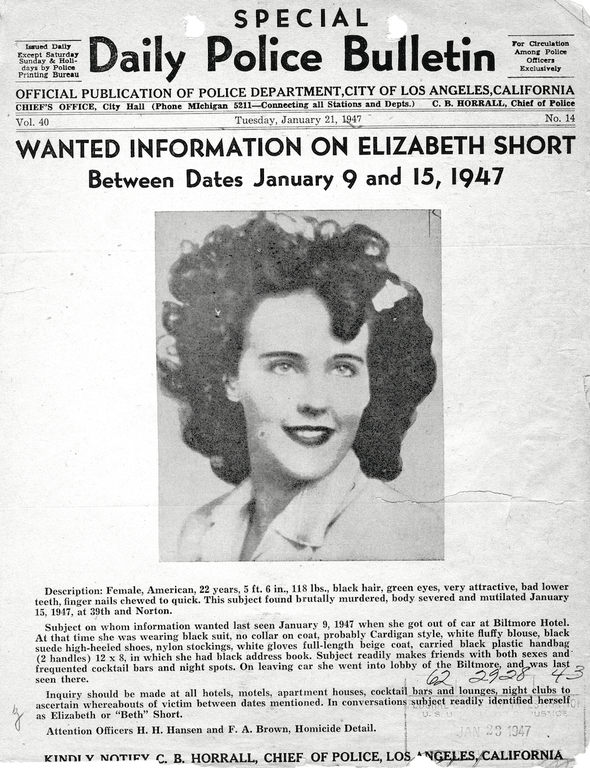

On the morning of January 15, 1947, a mother taking her child for a walk in a Los Angeles neighborhood stumbled upon a gruesome sight: the body of a young naked woman sliced clean in half at the waist.

On the morning of January 15, 1947, a mother taking her child for a walk in a Los Angeles neighborhood stumbled upon a gruesome sight: the body of a young naked woman sliced clean in half at the waist.

The body was just a few feet from the sidewalk and posed in such a way that the mother reportedly thought it was a mannequin at first glance. Despite the extensive mutilation and cuts on the body, there wasn’t a drop of blood at the scene, indicating that the young woman had been killed elsewhere.

The ensuing investigation was led by the L.A. Police Department. The FBI was asked to help, and it quickly identified the body—just 56 minutes, in fact, after getting blurred fingerprints via “Soundphoto” (a primitive fax machine used by news services) from Los Angeles.

The young woman turned out to be a 22-year-old Hollywood hopeful named Elizabeth Short—later dubbed the “Black Dahlia” by the press for her rumored penchant for sheer black clothes and for the Blue Dahlia movie out at that time.

Short’s prints actually appeared twice in the FBI’s massive collection (more than 100 million were on file at the time)—first, because she had applied for a job as a clerk at the commissary of the Army’s Camp Cooke in California in January 1943; second, because she had been arrested by the Santa Barbara police for underage drinking seven months later. The Bureau also had her “mug shot” in its files and provided it to the press.

In support of L.A. police, the FBI ran records checks on potential suspects and conducted interviews across the nation. Based on early suspicions that the murderer may have had skills in dissection because the body was so cleanly cut, agents were also asked to check out a group of students at the University of Southern California Medical School. And, in a tantalizing potential break in the case, the Bureau searched for a match to fingerprints found on an anonymous letter that may have been sent to authorities by the killer, but the prints weren’t in FBI files.

Who killed the Black Dahlia and why? It’s a mystery. The murderer has never been found, and given how much time has passed, probably never will be. The legend grows…