Crime and Corruption Across America, 1972-1988

A night guard at the Watergate Complex was making his rounds early one Saturday morning when he came across an exit door that had been taped open. He was immediately suspicious.

It was June 17, 1972, and he’d just uncovered what would become the most famous burglary in U.S. history.

Five men were arrested by police a few minutes later for breaking into the Democratic National Committee Headquarters inside the Watergate. Police also found fake IDs, bugging equipment, and lookouts in the motel across the street.

Things snowballed from there. President Richard Nixon’s reelection campaign had not only been caught committing an illegal political dirty trick, but the administration reacted by lying and covering up the crime and others. Two years later, President Nixon resigned rather than face certain impeachment.

From the moment that police realized the Watergate break-in was no ordinary burglary, the FBI was on the case. But the timing couldn’t have been worse. It had been less than five weeks since J. Edgar Hoover—the only Director FBI employees had known—had died in his sleep. For years, criticism of the Bureau and Hoover had been building. There was dissatisfaction with Hoover’s age, increasing political disagreement over the Bureau’s tactics and techniques, and widespread unease over the chaos and violence of the late 1960s.

Acting FBI Director L. Patrick Gray testifies. AP Photo.

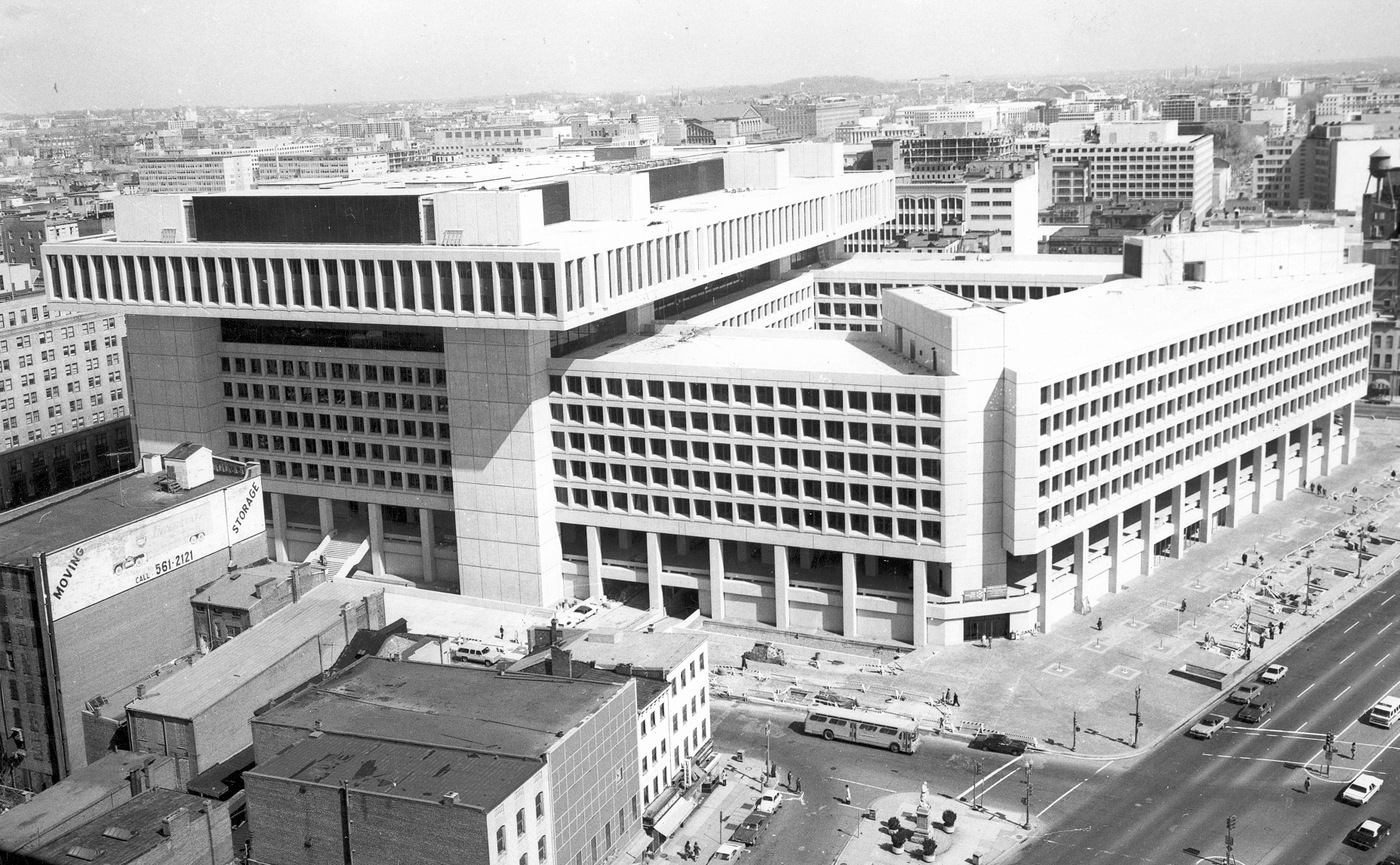

The Watergate Complex. The break-ins occurred in the office building in the center.

Now, the FBI was about to become involved in the most politically sensitive investigation in its history.

During the Watergate scandal, the FBI faced political pressure from the White House and even from within its own walls—Acting Director L. Patrick Gray was accused of being too pliable to White House demands and resigned on April 27, 1973. And throughout, a high-ranking official—dubbed “Deep Throat” and ultimately identified in 2005 as FBI Deputy Director Mark Felt—was leaking investigative information to the press.

Still, FBI agents diligently investigated the crime and traced its hidden roots, working closely with the special prosecutor’s office created by the Attorney General and with the Senate Select Committee on Presidential Campaign Activities. Nearly every Bureau field office was involved in the case. Agents prepared countless reports and conducted some 2,600 interviews requested by the special prosecutor. The FBI Laboratory and Identification Division also lent their services. In the end, the Bureau’s contributions to unraveling the Watergate saga were invaluable.

In the midst of Watergate, the Bureau had gained new leadership. Clarence Kelley, a former FBI agent and Kansas City, Missouri, Chief of Police, took office on July 9, 1973. Kelley had the tough task of moving the FBI into the post-Hoover era. He did an admirable job of restoring public trust in the agency, frankly admitting that mistakes had been made and leading a number of far-reaching and necessary reforms.

FBI Deputy Director Mark Felt, who later admitted to being “Deep Throat.”

During the 1970s, more women began joining the ranks of the FBI, including (for the first time since the 1920s) as special agents.

In response to criticism of the Bureau’s Cointelpro operation, for example, he reorganized FBI intelligence efforts. In February 1973, the General Investigations Division took over responsibility for investigating domestic terrorists and subversives, working under more strict guidelines and limiting its efforts to actual criminal violations. The Intelligence Division retained foreign counterintelligence responsibilities but was renamed the National Security Division

Kelley’s most significant management innovation was shifting the FBI’s longstanding investigative focus from “quantity” to “quality,” directing each field office to set priorities based on the most important threats in its territory and to concentrate their resources on those issues.

And what were those threats? During the 1970s, domestic terrorism and foreign intrigue remained key concerns, as the radical unrest of the 1960s had spilled into the next decade and the Cold War was still raging. The FBI had its hands full with homegrown terrorist groups like the Symbionese Liberation Army—which wanted to lead a violent revolution against the U.S. government and kidnapped newspaper heiress Patty Hearst to help its cause—and the Weather Underground, which conducted a campaign of bombings that targeted everything from police stations to the Pentagon. And spy cases still abounded—from the “Falcon and the Snowman” investigation that uncovered two former altar boys from wealthy families selling secrets to the Soviets…to “Operation Lemon-Aid,” where the FBI used a double agent to unmask Soviet diplomats working as KGB spies.

The FBI Academy at Quantico

In 1972, today’s FBI Academy—which trains not only Bureau personnel but also law enforcement professionals from around the globe—opened its doors on a sprawling 385-acre campus carved out of the Quantico Marine Corps base in rural Virginia.

How did the Bureau end up at Quantico? It all started in 1934, when Congress gave agents the authority to carry firearms and make arrests. The Bureau needed a safe, out-of-the-way place to learn marksmanship and to take target practice. The U.S. Marine Corps was ready to help, loaning a firing range at its base in Quantico, about 35 miles southwest of Washington, D.C.

| ||||

| ||||

Top: An aerial view of the FBI Academy Above: A few buildings at “Hogan’s Alley,” |

By the late 1930s, the FBI needed a central place to instruct and house the growing number of police officers and special agents it was training, along with a range that met the Bureau’s more specialized law enforcement work. So in 1939, the Marine Corps loaned the Bureau land to build its own training facility and firing range. The first FBI classroom building opened on the main section of the base in 1940. The FBI Academy was born.

Over the next two decades, the FBI added to the original building. But it still wasn’t enough. Eight people shared a single dorm room. The lack of classroom space limited the size of training classes. The firing range was a bumpy bus ride away. The FBI needed the facilities to match its vision for world-class training. In 1965, the FBI got approval to build a brand new complex at Quantico. The Marine Corps obliged once again, loaning more acres on the outskirts of the base.

On May 7, 1972, the new, expanded, and modernized FBI Academy was opened. Talk about a major upgrade: the complex included more than two dozen classrooms, eight conference rooms, twin seven-story dormitories, a 1,000-seat auditorium, a dining hall, a full-sized gym and swimming pool, a fully equipped library, and new firing ranges. Not to mention much-needed enhancements like specialized classrooms for forensic science training, four identification labs, more than a dozen darkrooms, and a simulated-city and crime scene room for practical exercises.

Since 1972, the Academy has continued to grow and evolve, both in terms of its training and its facilities. In 1976, the FBI created the National Executive Institute for the heads of the nation’s largest law enforcement agencies. More leadership training programs have followed. In 1987, the Bureau built a mock town on campus called “Hogan’s Alley,” providing a realistic training ground for agents.

Joining the Academy complex in the 1980s and 1990s were the Engineering Research Facility and the Critical Incident Response Group, which includes the FBI’s Hostage Rescue Team and behavioral scientists. In 2002, the FBI also launched the College of Analytical Studies—now called the Center for Intelligence Training—to develop and train its cadre of intelligence analysts. The following year, the Bureau opened its first ever standalone Laboratory building, a state-of-the-art facility that helps the FBI continue its pioneering work in forensic science.

The Bureau was also increasingly turning its focus to big-time crime and corruption across the nation. For the first time, Kelley made combating organized crime and white-collar crime national investigative priorities. And the Bureau went after them in a big way.

Organized crime was certainly nothing new in America. The Italian imported “La Cosa Nostra”—literally translated as “this thing of ours”—had come to the nation’s attention in 1890, when the head of the New Orleans police department was murdered execution-style by Italian and Sicilian immigrants. In the 1930s, Charles “Lucky” Luciano had set up the modern-day La Cosa Nostra, creating the family structure (led by “dons” or “bosses”) and ruling body (“the Commission”) and running the entire operation like a business.

The FBI moved into its massive new Headquarters building in Washington, D.C., beginning in June 1974.

By the 1950s and 1960s, organized crime had become entrenched in many major cities, and the collective national impact was staggering. Mobsters were feeding American vices like gambling and drug use; undermining traditional institutions like labor unions and legitimate industries like construction and trash hauling; sowing fear and violence in communities; corrupting the government through graft, extortion, and intimidation; and costing the nation billions of dollars through lost jobs and tax revenues.

Though somewhat limited in its authorities, the Bureau had begun targeting mobsters early as the 1930s, using a mixture of investigations and intelligence to break up mob rackets. Following revelations at Apalachin, New York, the FBI had stepped up its efforts. By 1970, the FBI had gained some important new tools to go after mobsters—including court-authorized wiretaps, jurisdiction over mob-infiltrated businesses, and the ability to target entire crime families and their leaders instead of just bit players and isolated wise guys.

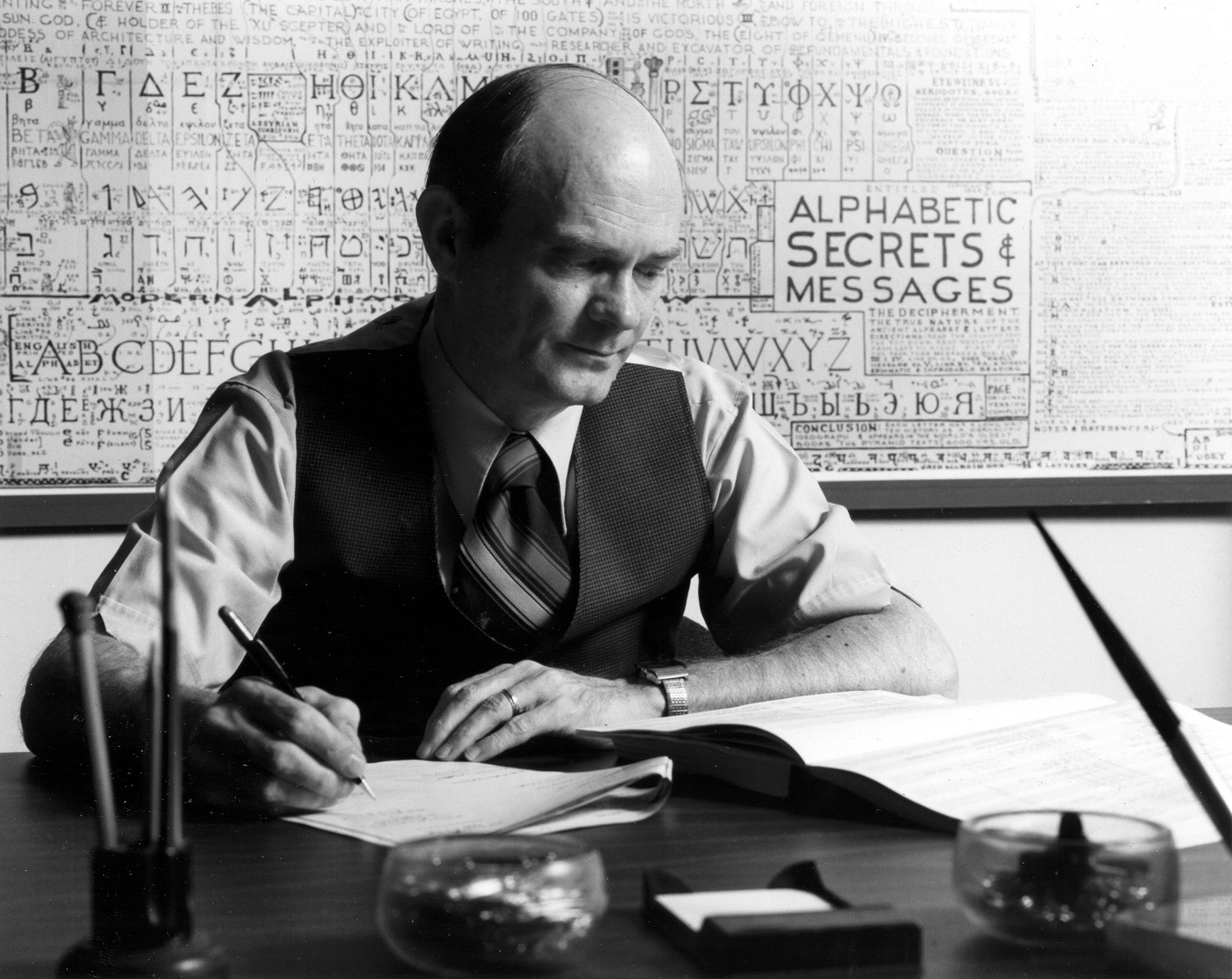

An cryptologist at the FBI Laboratory works to break codes in the 1970s.

In the mid-1970s, the FBI began pioneering some tools and strategies of its own. It started turning high-level mobsters into secret informants, breaking the code of silence, or “Omerta,” that had protected top Mafioso for so long. And it began using long-term undercover operations—governed by new guidelines and policies—to penetrate the inner circles of organized crime. The courageous work of undercover agents like Joe Pistone—who almost became a “made” Mafia member while gathering invaluable intelligence as “Donnie Brasco” for nearly six years—and of cooperating witnesses like businessman Lou Peters—whose Cadillac dealership became the basis for a long-term operation that targeted the Bonnano crime family in California—injected new energy into FBI investigations and intelligence work.

Using these strategies and tools, the Bureau started racking up unprecedented successes against organized crime. Beginning in 1975, for example, a case code-named “Unirac” (for union racketeering) broke the mob’s broad stranglehold on the shipping industry, leading to more than 100 convictions. In a two-part operation launched in 1978, the FBI struck a major blow against organized crime leadership in Cleveland, Milwaukee, Chicago, Kansas City, and Las Vegas through an investigation that uncovered the mob’s corrupt influence in Las Vegas and in the Teamsters Union. And in the 1980s, the groundbreaking “Commission” case led to the convictions of the heads of the five Mafia families in New York City—Bonnano, Colombo, Gambino, Genovese, and Lucchese.

The so-called “Pizza Connection” case in the 1980s was a another key organized crime success—a joint investigation conducted by the FBI, New York and New Jersey police, federal and state prosecutors, and Italian law enforcement officials that cracked an intercontinental heroin smuggling ring run by the Sicilian Mafia. This case not only proved the effectiveness of undercover agents, wiretaps, and enterprise investigations, it also highlighted the increasingly important role of cooperation with international law enforcement.

From 1981 to 1987 alone, more than 1,000 Mafia members and associates were convicted following investigations by the FBI and its partners, decimating the hierarchies of crime families in New York City, Boston, Cleveland, Denver, Kansas City, Milwaukee, St. Louis, and the state of New Jersey. The Bureau also disrupted the activities of other organized criminal groups, tackling outlaw motorcycle gangs like Hells Angels and various Asian criminal enterprises that were beginning to take root in America.

At the same time, the FBI was tackling white-collar crime in a more systematic, comprehensive way.

The term “white-collar criminal” had been coined in 1939 by an American sociologist named Edwin Sutherland; a decade later, he defined a white-collar crime as one “committed by a person of respectability and high social status in the course of his occupation.”

From the days of Charles Ponzi—whose bogus investment scheme in 1919 has been replicated thousands of times since—white-collar crime has evolved into a significant national threat. Over time, more and more Americans have traded their factory and farm jobs for a seat in corporate America; by the beginning of the 21st century, some 60 percent of all workers had white-collar jobs, up from 17 percent a century earlier. White-collar crimes today include everything from anti-trust violations to bank fraud, from embezzlement to environmental crimes, from insider stock trades to health care fraud, from public corruption to property and mortgage scams. These crimes siphon billions of dollars from the pockets of the American people, hurt the economy by undercutting consumer confidence and legitimate commerce, and threaten the very health of our democracy.

FBI agents arrest a member of the New York Mafia in March 1988. Robert Maass/CORBIS.

A New Era in Domestic Intelligence

In the early 1970s, the nation began to learn about secret and sometimes questionable activities of the U.S. intelligence community—including the CIA and FBI—especially during the turbulent 1960s. In response, a Senate committee chaired by Frank Church, which later came to be known as the Church Committee, held a series of hearings in 1975 to explore the issue.

During the hearings on the FBI, the Bureau was criticized for its Cointelpro program, its investigation of Dr. King, its surveillance techniques, and the use of FBI information by politicians.

In his testimony before the committee, Director Kelley explained that Cointelpro represented only a small fraction of the FBI’s overall work. He also pointed out that the nation expected the FBI to respond vigorously to the violence and chaos of the 1960s, but that it was given few investigative guidelines by Congress. Still, the FBI recognized that it needed to reform its domestic security investigations and had already begun to do so before the hearings.

In 1976, Attorney General Edward Levi and the FBI came up with a series of guidelines on how the FBI should conduct domestic security operations. The key change: to only investigate radicals breaking the law or clearly engaging in violent activity. The reforms had an immediate and far-reaching impact: the number of FBI domestic security cases fell from over 21,000 in 1973 to just 626 by September 1976.

In 1978, partly in response to the Church Committee hearings, the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act, or FISA, was enacted. The law set rules for physical and electronic surveillance and the collection of foreign intelligence and established a special court to hear requests for warrants.

These changes established clearer parameters for FBI investigations and made agents more respectful than ever of the need to protect constitutional rights. At the same time, the criticism and ensuing reforms had a chilling effect on the Bureau’s intelligence work in the years to come, making the FBI more cautious and more willing to strictly delineate between national security and criminal investigations.

Among white-collar crimes, public corruption remains the most insidious. Watergate had opened the nation’s eyes to the seriousness of crime in government, and the FBI became convinced that it must be a leader in addressing the problem. Using many of the same tools as in its battle against organized crime, including large-scale undercover operations, it began working to root out crookedness in government.

One major undercover operation, code-named “Abscam,” led to the convictions of six sitting members of the U.S. Congress and several other elected officials in the early 1980s. “Operation Greylord” put 92 crooked judges, lawyers, policemen, court officers, and others behind bars in the mid-1980s. The “Brilab” (Bribery/Labor) investigation begun in Los Angeles in 1979 revealed how the Mafia was bribing government officials to award lucrative insurance contracts, and a major case called “Illwind,” culminating in 1988, unveiled corruption in defense procurement.

Other kinds of white-collar crime began to mushroom in the 1980s. As the United States faced a financial crisis with the failures of savings and loan associations during the 1980s, for example, the FBI uncovered many instances of fraud that lay behind many of those failures. In the coming years, frauds involving health care, telemarketing, insurance, and stocks would become major crime problems.

All during this time period, the FBI also had been expanding its capabilities and technologies and integrating new responsibilities into its work.

In 1978, the same year that Judge William Webster became Director, for instance, the Bureau began using laser technology to detect nearly invisible or “latent” crime scene fingerprints. At the new, modern FBI Academy, the Behavioral Sciences Unit pioneered work in criminal profiling—applying psychological insights to solving violent crimes. In 1984, the National Center for the Analysis of Violent Crime was established to further this research and to provide services to local and state police in identifying suspects and predicting criminal behavior.

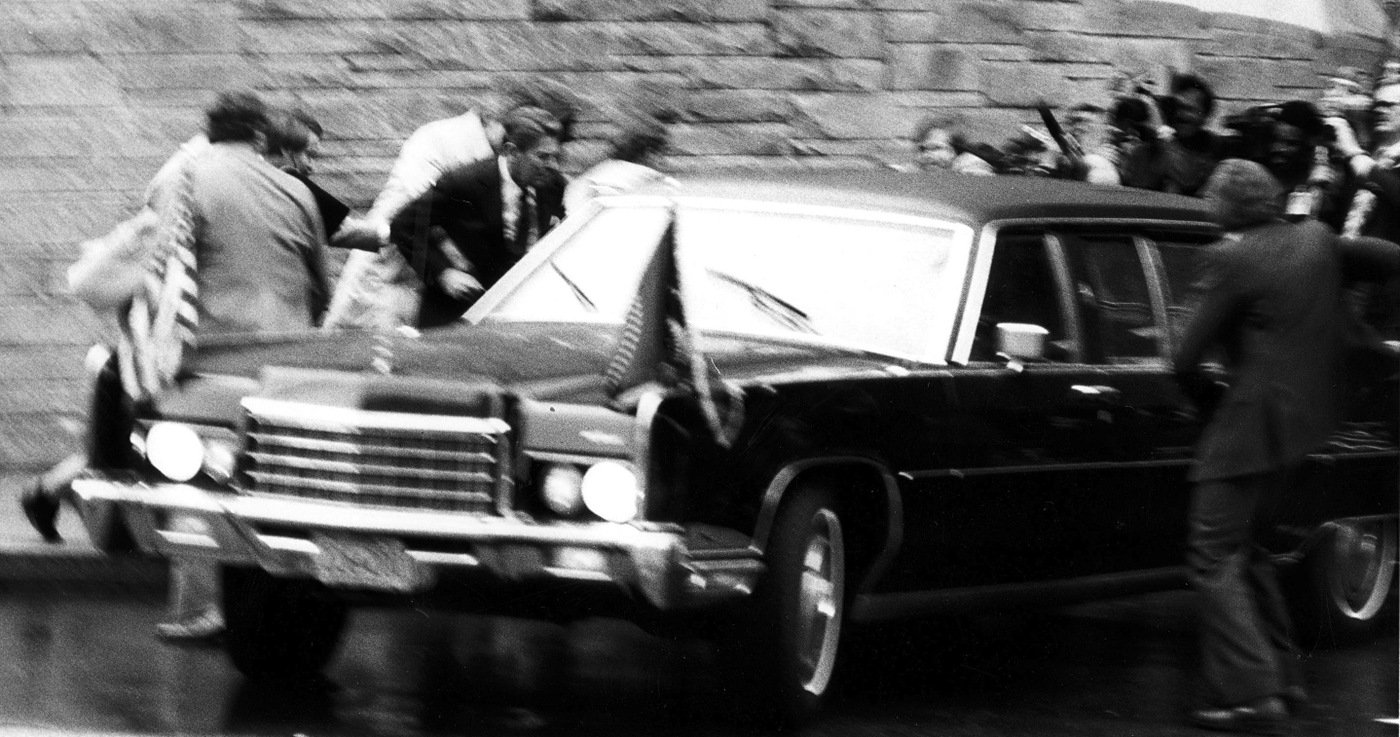

President Ronald Reagan right after being shot by John Hinckley on March 30, 1981. Following the attack, the FBI launched a massive investigation to determine Hinckley’s motives and whether or not others were involved in the assassination attempt. Tracing Hinckley’s life and movements across the country, the FBI concluded that he had acted on his own.

In 1982, the FBI was given concurrent jurisdiction with the Drug Enforcement Agency over federal anti-narcotics laws, which led to stronger liaison and division of labor in tackling the growing drug problem in America. That same year, following an explosion of terrorist incidents worldwide, Director Webster made counterterrorism the FBI’s fourth national priority. The Bureau was ready: it had already begun building new partnerships and skills to respond to and prevent both domestic and international terrorist attacks. The first Joint Terrorism Task Force in the nation, for example, had been created with the New York Police Department in 1980 to serve as the front-line defense against terrorism in the city. And in 1983, the Bureau had stood up a specially-trained Hostage Rescue Team to use negotiation and tactical response techniques to save lives during terrorist attacks and other hostage situations.

Director Webster also pressed for changes in the rules covering FBI national security investigations. In 1983, Attorney General William French Smith modified the guidelines for conducting intelligence investigations; the next year, Congress authorized the Bureau to pursue criminals who attacked Americans beyond our shores. That paid off quickly with the arrest of Fawaz Younis, who in 1987 became the first international terrorist to be apprehended overseas and brought back to the U.S. for trial. And with the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act that had been passed in 1978 and new laws that protected classified information in trials, so many moles in the U.S. government were arrested in the mid-1980s that the press dubbed 1985 the “Year of the Spy.”

The Hostage Rescue Team, created in 1983, trains at Quantico. The team has been involved in many high-profile cases and deployed on more than 200 missions in the U.S. and abroad.

The FBI Laboratory continued to break new ground as well. By researching processes to match DNA samples obtained from evidence at a crime with samples obtained from suspects, FBI scientists contributed to a whole new field of forensic science that helps catch the guilty and free the innocent. In 1988, the FBI Lab became the first facility in the nation to perform DNA analysis for criminal investigations, and it launched a national DNA database as a pilot program three years later.

By this time, Director Webster had left the Bureau—he was asked to serve as the Director of Central Intelligence and head of the CIA in the summer of 1987. He was replaced later that year by another federal judge, William Sessions, who would oversee the Bureau as the Cold War ended and its priorities gave way to the challenges of a multi-polar, globalized world.

Profiling: Inside the Criminal Mind

For 16 long years, a serial bomber had been terrorizing New York City by setting off bombs in public places around town. Having exhausted every investigative angle, police turned to a Greenwich Village psychiatrist named James Brussels in 1956 for his insights into the so-called “Mad Bomber.”

For 16 long years, a serial bomber had been terrorizing New York City by setting off bombs in public places around town. Having exhausted every investigative angle, police turned to a Greenwich Village psychiatrist named James Brussels in 1956 for his insights into the so-called “Mad Bomber.”

By analyzing the bomber’s letters and targets and studying crime scene photos, Brussels came up with a profile of the bomber. It was remarkably accurate—down to the buttoned, double-breasted suit that Brussels theorized the bomber would wear. This portrait soon led police to a disgruntled power company employee named George Metesky, who immediately confessed.

From these first few modern-day steps—further developed in New York and in other cities and used in such cases as the “Boston Strangler”—the art and science of what is now called criminal profiling or behavioral analysis started to develop in a piecemeal fashion.

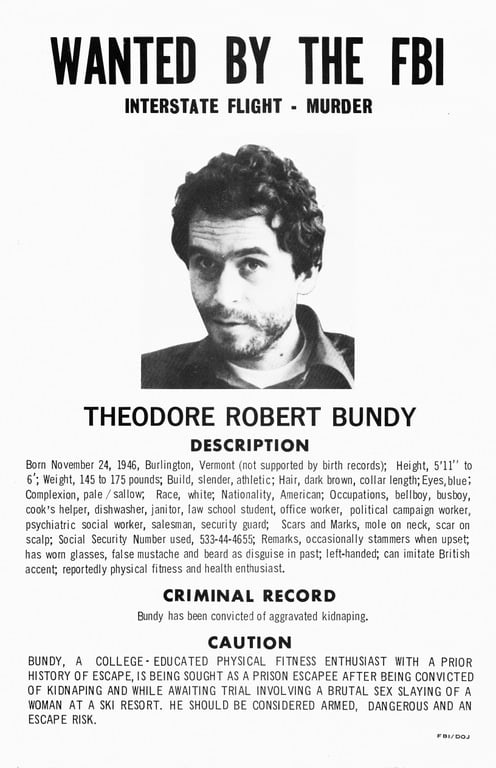

In the early 1970s, Special Agent Howard Teten and others in the Bureau began to apply the insights of psychological science to violent criminal behavior in a more comprehensive way. In 1972, the FBI Academy launched a Behavioral Science Unit—later called the Behavioral Analysis Unit—which began looking for patterns in the behavior of serial rapists and killers. Agents John Douglas and Robert Ressler conducted systematic interviews of serial killers like John Wayne Gacy, Ted Bundy, and Jeffrey Dahmer to gain insight into their modus operandi, motivations, and backgrounds. This collected information helped agents draw up profiles of violent criminals eluding law enforcement.

By the 1980s, the concept of criminal investigative analysis was maturing into a full-fledged investigative tool for identifying criminals and their future actions by studying their behaviors, personalities, and physical traits. Accordingly, in July 1984, the Bureau opened the National Center for the Analysis of Violent Crime (NCAVC) on the campus of the FBI Academy to provide sophisticated criminal profiling services to state and local police for the first time.

Today, the center includes several Behavioral Analysis Units and the Violent Criminal Apprehension Program, which helps law enforcement investigate and track violent serial offenders. NCAVC provides a variety of services to law enforcement and offers research into a range of crime problems—from serial arsonists to child molesters to school shooters.

Over the years, FBI behavioral experts have contributed to the hunt for the following serial killers:

- Wayne Williams, who preyed on African American children in Atlanta during the 1980s.

- Andrew Phillip Cunanan, a Top Ten Fugitive wanted for the murder of fashion designer Gianni Versace and several others in the late 1990s.

- The D.C. Snipers—John Allen Mohammed and Lee Boyd Malvo—who terrorized the nation’s capital with random shooting for 23 days in 2002.

- Dennis Rader—aka the BTK killer, for “Bind them, Torture them, Kill them”—who murdered 10 people in Kansas between 1974 and 1991 before his arrest in 2005.