A New Era of National Security, 2001-2008

American Airlines Flight 11 had just left Boston and was climbing to its final flying altitude in the clear blue skies over central Massachusetts when a handful of Middle Eastern terrorists suddenly stormed the cockpit and took control of the aircraft.

It was 8:14 in the morning on September 11, 2001.

By 9:37 a.m., Flight 11 and two more hijacked planes had slammed into the twin towers of the World Trade Center and the Pentagon. By 10:03, terrorists had dive-bombed a fourth plane into a rural field in Pennsylvania after its passengers and crew heroically rebelled. By 10:30, nearly 3,000 men, women, and children had been killed—many in the most horrific of ways, in fierce fireballs and falling towers.

In the world of crime, you’d call it first-degree murder: deliberate, premeditated, cold-blooded.

The terrorist attacks that unfolded on the morning of 9/11—carried out by al Qaeda operatives under orders from Usama bin Laden—were that and much more. They were the largest mass murder in American history, a calculated slaughter of civilians, an overt act of aggression and war that took more lives and did more damage than the sneak attack at Pearl Harbor.

For the FBI—and the nation—a new era of national security had begun.

Two FBI agents at the site of the World Trade Center in New York on September 16, 2001. Reuters.

The second hijacked airplane moments before it crashes into the south tower of the World Trade Center at 9:03 a.m. AP Photo.

That reality was certainly clear to Robert Mueller—the newly-minted director of the FBI. He’d walked in the door on September 4, 2001 with a mandate to reform and modernize the Bureau—particularly following debacles involving FBI agent-turned-Soviet mole Robert Hanssen, the botched Wen Ho Lee espionage investigation, and shoddy record-keeping in the Oklahoma City bombing case. But exactly one week later, his job description underwent a seismic shift.

On the morning of 9/11 and in the days that followed, Mueller focused the energies of the Bureau on the unfolding, around-the-clock investigation—soon to be the largest in its history, with a quarter of all FBI agents and personnel directly involved—and more importantly, into making sure that a second wave of terrorists wasn’t waiting in the wings to strike the country again.

The FBI succeeded on both counts. Agents and analysts identified the 19 hijackers within days, learned everything they could about them and the 9/11 plot, and gathered definitive proof linking the attacks to al Qaeda—all while helping to harden security vulnerabilities and prevent any further attacks.

But the Director also knew that when the dust settled, the FBI would never be the same again.

If 9/11 was a failure of imagination—as journalist Tom Friedman put it, referring to America’s inability to conceive of such a horrific plot—Mueller and his top brass recognized that they would have to re-imagine the FBI for the 21st century. The Bureau’s range of capabilities and its tactical response to the crime and crisis of the moment were still first rate, but the attacks showed that its strategic capabilities had to improve. The FBI needed to be more forward-leaning, more predictive, a step ahead of the next germinating threat. And most importantly, it needed to become adept at preventing terrorist attacks, not just investigating them after the fact.

The key to that new mandate, Director Mueller knew, was intelligence—the holy grail of national security work, the ability to collect and connect the dots, to know your enemies and the threats they pose inside and out, to arm everyone from leaders in the Oval Office to police officers on the street with information that enables them to stop terrorist and criminal plots before they are carried out.

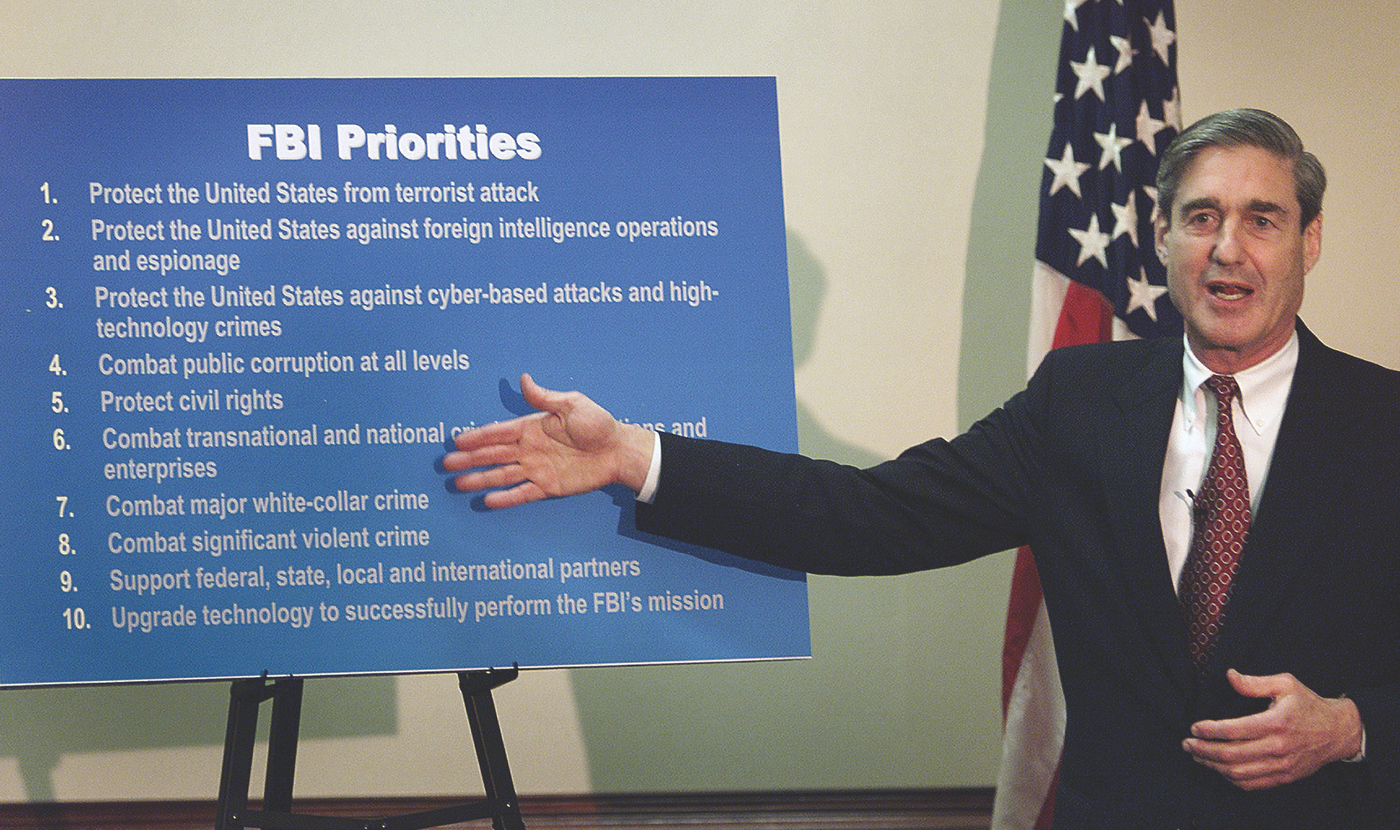

On May 29, 2002, Director Mueller announced a new set of 10 priorities for the FBI and discussed the reorganization of the Bureau in response to the 9/11 attacks. AP Photo.

The Bureau has been in the intelligence business since its earliest days. It used intelligence and intelligence-led strategies to knock out emerging threats in World War I; to dismantle Nazi and Soviet spy rings in the U.S. during World War II and the Cold War; to penetrate and take down entire organized crime families; and to head off dozens of terrorist plots before 9/11.

But, over the years, the FBI had often focused on making quick arrests rather than turning suspects into opportunities to collect every scrap of information about a threat…on developing comprehensive cases rather than on making prevention the overarching prime directive behind all cases. Because of longstanding neglect of information technology, the Bureau lacked the capacity to “know what it knows”—to turn all the bits of intelligence streaming in from around the world into meaningful assessments and actionable information. And it wasn’t generating nearly enough quality analysis or sharing information as much as it could both inside and outside its own walls.

In the weeks and months following the attacks, all of this began to change—in a big way. Working from its own conclusions and, later, from the comprehensive reports prepared by the 9/11 Commission and other independent bodies, the FBI immediately started reshaping itself into an intelligence-driven agency and strengthening its counterterrorism operations.

The Threat of Threats: WMD

| ||||||

| ||||||

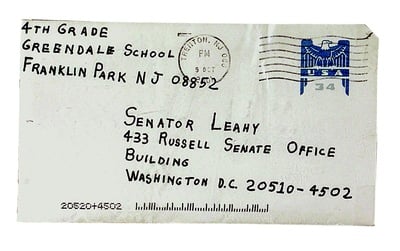

A letter addressed to Senator Patrick Leahy being opened by experts |

It’s what Director Mueller says keeps him awake at night: terrorists or other dangerous actors getting their hands on weapons of mass destruction—whether biological, chemical, radiological, or nuclear—and using them against the United States.

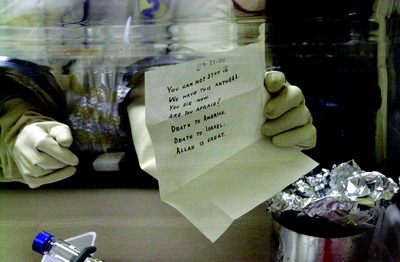

The threat is real. Al Qaeda has openly pursued WMD. And just days after 9/11, America experienced the worst biological attack in its history when letters laced with a highly potent strain of anthrax suddenly began appearing in the U.S. mail. By month’s end, five Americans were dead and many more sickened. The complex FBI-led investigation—code-named “Amerithrax”—grew into a massive operation and led to scientific advances that greatly strengthened the nation’s ability to prepare for and investigate biological attacks. In the summer of 2008, the FBI was preparing to indict anthrax researcher Dr. Bruce Ivins in connection with the mailings, but he took his own life before charges could be filed.

In July 2006, as part of its evolving response to terrorism threats, the FBI consolidated all of its WMD operations into a new Weapons of Mass Destruction Directorate within its National Security Branch.

The Directorate has since spearheaded new outreach initiatives with private industry and public partners to build awareness and encourage information sharing, including teaching companies and universities what they need to know to help prevent WMD attacks and providing them with vulnerability assessments.

The Directorate has also developed proactive, multi-layered preparedness strategies with academia, government agencies, and strategic global allies and integrated intelligence into its daily work to help FBI agents and the nation as a whole to better understand and counter evolving threats.

The pieces soon began falling into place.

Structurally, the entire counterterrorism operation was reorganized and expanded, with FBI Headquarters taking on oversight of terrorism cases nationwide to strengthen accountability and coordination with other agencies and governments. In September 2005, by presidential directive, this restructuring took another step forward with the creation of the National Security Branch, which consolidated FBI counterterrorism, counterintelligence, and intelligence responsibilities into a single “agency within an agency.”

Operationally, the FBI started adding and augmenting capabilities at every turn. At the field office level, the Bureau quickly doubled and ultimately tripled the number of its multi-agency Joint Terrorism Task Forces—teams of highly-trained, passionately-committed investigators, analysts, linguists, bomb experts and others from dozens of law enforcement and intelligence agencies—mandating them to run down any and all leads and to become intelligence-gathering hubs. Back in Washington, these task forces were supported by a new National Joint Terrorism Task Force working in the heart of FBI Headquarters to cycle information among local task forces and participating agencies. The FBI also created, for the first time, a dedicated team of financial experts to follow terrorist money trails and a global command center called “Counterterrorism Watch” to assimilate and triage emerging threats and suspicious activities. And it started using sophisticated risk assessments and tracking tools to stop terrorists at the border and to track their footprints within the United States.

Technologically, the Bureau began putting sophisticated new IT tools in the hands of its agents, analysts, and other professionals—from easily searchable electronic warehouses of terrorism data to a web-based information management system that makes it easier to keep tabs on cases and share and access records. New information pipelines were also built so that the FBI could speed classified materials along to its partners.

All the while, an intelligence-driven approach was being ingrained into the FBI in important new ways.

A new Office of Intelligence—later expanded into a full-fledged Directorate of Intelligence—was created in December 2001 to lay the right foundation: to standardize policies and processes; to recruit new talent and improve training; to develop career tracks for analysts; and to create reports officers who could scrub intelligence of sources and methods and share it far and wide. Within two years, new field intelligence groups had been established in every field office to take raw information from local cases and make big-picture sense of it, to fill gaps in national cases with local information, and to share their findings and assessments as widely as possible. The growing result was that the FBI really began to flex its intelligence muscle—creating more and better analytical products, sharing information more widely at all levels, connecting dots in ways it could have never done before.

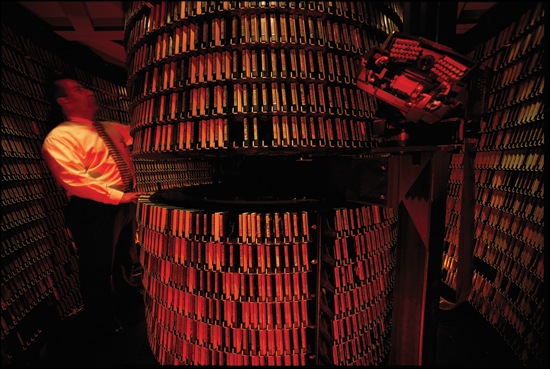

A robotic arm retrieves and re-files magnetic tapes containing fingerprint records at the FBI’s Criminal Justice Information Services Division in West Virginia in 2002. Bettmann/Corbis photo.

One key breakthrough came at the hands of Congress and the courts. In part because of prevailing interpretations, a legal “wall” existed between intelligence and criminal investigations prior to 9/11—which kept FBI agents and analysts in the dark about the work of their own colleagues and prevented important evidence from ever reaching the courtroom. Following the attacks, thanks to new legislation and court decisions, that wall came down, and the impact has been profound. The Bureau is now free to coordinate intelligence operations and criminal cases and to use the full range of investigative tools against a suspected terrorist. The right hand now knows what the left hand is doing—an imperative for prevention.

Another imperative is partnerships. The FBI has spent a century building many positive law enforcement and intelligence-based relationships across every level of government and even across borders. Since 9/11, thanks to a new collective determination to defeat terrorism and the growing globalization of crime, these relationships are broader and deeper than ever before. They’ve improved at every level: with state, local, and tribal law enforcement; with foreign governments; with intelligence community partners like the CIA; with the U.S. military; and with the private sector and academia. Today, more information and intelligence is shared more freely with more partners. More agents and officers and analysts physically sit together, including in dozens of intelligence fusion centers nationwide and in the new multi-agency National Counterterrorism Center. Joint investigations and joint task forces are the norm, especially in the U.S. and increasingly overseas, and the FBI is working alongside U.S. forces in war zones overseas for the first time in history. Effective partnerships don’t make news, but they have truly been a game changer for the FBI and its colleagues across the globe.

The cumulative impact of all these changes and reforms has been some major operational successes in the U.S. and overseas. Sometimes by providing vital bits of intelligence, sometimes by joining dangerous raids overseas, the FBI has helped capture key al Qaeda leaders—from 9/11 mastermind Khalid Shaikh Mohammed to operations chief Abu Zubaydah—in Pakistan and elsewhere. Quite often, one terrorist has led to another and to another—yielding new streams of intelligence on terrorist threats and leads that exposed operatives and cells, some in the process of planning attacks.

Most importantly, the Bureau’s work helped prevent dozens of terrorist strikes around the globe—in ways that could not always be made public. Working through its terrorism task forces, the FBI stopped homegrown plots to bomb military bases and Jewish synagogues in Los Angeles; to blow up fuel tanks at J.F.K. Airport in New York; to shoot up soldiers at Fort Dix in New Jersey; and to attack suburban malls in Illinois and Ohio. It rolled up cells in places like Buffalo, Portland, and Northern Virginia. And it helped put behind bars extremists like Richard Reid, the so-called “Shoe Bomber,” who attempted to blow up an airliner in mid-flight over the Atlantic Ocean; Iyman Faris, an Ohio truck driver who was feeding information on U.S. targets to al Qaeda; and a variety of other terrorist supporters and financiers.

Partnerships: The Next Generation

| |||

The National Counterterrorism Center—led by the Director of National |

In this complex, globalized, post-9/11 world, the FBI’s operational partnerships have never been more important to its efforts to protect the nation.

Today, the FBI works with colleagues at every level of government—local, state, tribal, federal, even international—across the law enforcement, intelligence, and first responder communities. It leads and participates in multi-agency task forces, intelligence groups and fusion centers, and public and private sector alliances. Many partners sit shoulder-to-shoulder with agents and analysts in FBI space, just as just as the Bureau shares its agents and analysts with other agencies. The FBI works on countless joint investigations—sometimes taking the lead, sometimes taking a back seat to others, sometimes contributing equally among many agencies. The Bureau’s work with its colleagues is so intertwined that it’s often nearly impossible to separate the contributions of one agency—and one nation—from the next.

A few examples of how the FBI’s relationships have been lifted to entirely new levels since 9/11, especially in the fight against terrorism:

Law Enforcement: More than ever, local and state law enforcement is an integral part of FBI counterterrorism efforts. The FBI now provides its police partners with more and better information, such as new intelligence bulletins that detail emerging trends on terrorism and potential issues to look out for. A new FBI Office of Law Enforcement Coordination, headed by a former police chief, has built stronger relationships with national law enforcement organizations. The FBI has provided its partners with a variety of new tools and resources, too—including the Terrorist Screening Center, which enables police officers to find out right in their squad cars whether individuals they have detained have terrorist links or are wanted by the FBI for questioning.

The CIA: For the first time, the FBI and CIA are working off the same page—literally—through a common daily threat matrix that lays out every current terrorist threat and through regular briefings with other members of the intelligence community. The two agencies have integrated not only their intelligence but also their operations, swapping many more executives and analysts and even working together in a common space—symbolically, without walls—at the National Counterterrorism Center, the country’s new focal point for synthesizing terrorism intelligence.

The U.S. Military: Since 9/11, the FBI has worked side-by-side with the military in theaters of war. Hundreds of FBI employees have been embedded with armed forces in Iraq and Afghanistan on a rotating basis, working together to interview detainees, collect fingerprints and DNA samples, gather intelligence, analyze information and explosive devices, conduct raids, and secure terrorist safe houses.

International Liaison: A new spirit of teamwork has emerged overseas since 9/11. More cases are being worked jointly, more information and intelligence is being shared, and overall cooperation is greater than ever before. Just as nations around the world have provided unprecedented support to the Bureau since the attacks, the FBI has been able to return the favor through its growing expertise—providing vital bits of intelligence that has turned up terrorists across the globe and sending teams to help investigate bombings and attacks in Pakistan, Kenya, Spain, Morocco, Indonesia, Bali, the U.K., and elsewhere.

Even as the Bureau was making terrorism its top priority—and fundamentally changing the way it does business—its traditional criminal threats were mutating and growing in dangerous ways and demanding plenty of attention of their own. Street gangs—as destructive and violent as ever—were multiplying and migrating to new parts of the nation. Accounting shenanigans in corporate suites led to the fall of some big businesses—Enron, WorldCom, Qwest, to name a few—ringing up tens of billions of dollars in shareholder losses along the way. Public corruption, deemed the FBI’s top criminal priority because it tears at the fabric of American democracy, continued to rear its ugly head, with FBI cases finding evidence of graft and greed among sitting U.S. Congressmen, state governors, and big city mayors. Even levels of violent crime, long in decline nationwide, crept upward in many cities for a few years starting in 2004.

In the days following 9/11, the FBI had to make some hard choices about resources. Its prevention and counterterrorism mandates required it to move more than a thousand agents to national security programs. This meant that the FBI had to leave some crimes—like local bank robberies, smaller ticket frauds, and certain drug investigations—to its partners.

After the Storm

Hurricane Katrina was one of the strongest storms in history—and it struck the Gulf Coast with a vengeance in late August 2005.

Hurricane Katrina was one of the strongest storms in history—and it struck the Gulf Coast with a vengeance in late August 2005.

As Katrina made landfall in the city of New Orleans, the FBI stood its ground—with several agents staying behind to look after the office. The Bureau has worked ever since to help with recovery efforts and to combat the rising tide of crime and corruption that followed in the wake of the hurricane.

Hours after Katrina struck, the FBI had some 500 agents and other personnel from around the country helping to secure the city, answer emergency calls, patrol the streets, conduct search and rescue operations, and identify victims.

In the months that followed, the Bureau led a series of public safety initiatives to support area law enforcement and teamed up with local and federal authorities in the region and around the nation to stem the flood of scams preying on hurricane victims.

Early on, Director Mueller decided that the Bureau’s role on the criminal side of the house had to shift to targeting the largest threats—the major national and international illicit enterprises and mega-crimes that the FBI is best suited to address. Its strategy, as in counterterrorism, has been to let intelligence lead the way and to leverage the expertise of its many partners.

This strategy has been visible in just about every investigative program—from the new Law Enforcement Retail Partnership Network that tackles the burgeoning problem of organized retail theft…to the National Gang Intelligence Center that targets the most dangerous street gangs using integrated information from around the world…to the raft of new and improved cyber programs, initiatives, and multi-national alliances that tap into the collective wisdom of the public and private sectors.

On the Ground in Iraq and Afghanistan

| ||||

| ||||

Top: The aftermath of a car bombing in Baghdad in August 2003. |

Outside of its limited work following World War II, the FBI has never gathered intelligence quite like this—in war zones, working right alongside the military, scooping up everything from pocket litter to entire buildings full of seized documents.

When U.S. forces entered Afghanistan shortly after 9/11 and Iraq in March 2003, a team of FBI agents, analysts, and translators were right there with them, whether in caves or palaces, combing for terrorism information. FBI personnel seized vital documents, made a first-cut analysis of their value, and then shipped them back home for further study. Thousands of investigative leads and troves of intelligence resulted from these efforts.

In March 2005, the FBI put down official roots in Iraq, opening an office in the U.S. Embassy in Baghdad. Today, the Bureau has dozens of special agents, intelligence analysts, and other professionals in the country—one of its largest international contingents. The FBI’s work there includes:

- Interviewing suspected terrorists captured by the military for information about terrorist operatives and operations both inside and outside Iraq and possibly even in the United States;

- Gathering intelligence, which is quickly processed, analyzed, and shared, sometimes leading to still more intelligence, creating a lightning fast real-time intel cycle;

- Collecting evidence from crime scenes—whether from a massive car bomb or a mass grave;

- Helping to rescue kidnapped Americans;

- In concert with other U.S. agencies, investigating crimes committed by Americans against the Iraqi people, as well those Iraqis commit against their fellow citizens; and

- Helping to train police and intelligence forces in Iraq.

At the invitation of the Afghanistan government, the FBI also established a Legal Attaché office in Kabul in 2005. The FBI’s role in the country is primarily counterterrorism-based: interviewing members of al Qaeda and the Taliban who are captured by U.S. and international security forces and addressing terrorism leads and issues developed in the country and elsewhere.

In April 2003, the FBI Laboratory moved into its first standalone facility. The building, located on the campus of the FBI Training Academy in Quantico, Virginia, tripled the Lab’s workspace and included new state-of-the-art technologies and equipment.

On a larger scale, the Bureau began accelerating its evolution into a single, unified law enforcement and intelligence enterprise by standardizing operations and processes in the field and integrating intelligence activities into all investigative efforts. Each Bureau field office was tasked to systematically identify threats and vulnerabilities in their domain, to proactively direct resources to collect against those threats, to quickly share information with partners locally and nationally, and to evaluate the implications of that information on the larger threat picture. Through this continuous intelligence cycle and feedback loop, the FBI has been better able to adapt itself to emerging and evolving threats.

In the seven years following the 9/11 attacks, the Bureau has come a long way. It has taken its counterterrorism capabilities to an entirely new level. It has built the strongest set of multi-agency and multi-national partnerships in its history. It has created a set of modern tools and technologies for its agents and professional staff. As a result, the FBI has become an agency that is skilled at both preventing and investigating attacks—and at using intelligence to be a step ahead of the bad guys. Despite the nearly constant adjustments the Bureau has made over the past century, the post 9/11 shift has represented one of the most dynamic transformations in the history of the FBI.

And yet, the FBI realizes that the journey is far from over. There are more improvements to make, more technologies to be rolled out, more scientific tools to be pioneered, more capabilities to be developed and refined. And if the Bureau has learned anything over the last 100 years, it is that there is always a new security threat just around the corner. In the FBI’s business, there is no room for complacency.

What will the next century bring for the FBI? Only time will tell, but the men and women of the Bureau move forward building on a solid foundation—on a century’s worth of innovation and leadership, on a track record of crime-fighting that is perhaps second to none. Along the way, the FBI has shown that it is resilient and adaptable, able to learn from its mistakes. It has built up a full complement of investigative and intelligence capabilities that can be applied to any threat. And it has gained plenty of experience in balancing the use of its law enforcement powers with the need to uphold the cherished rights and freedoms of the American people.

The FBI can look back proudly on a long history of protecting the people and defending the nation…and it can look confidently to the future, ready for the challenges ahead.

Interviewing Saddam: Teasing Out the Truth

An FBI agent fingerprints Saddam Hussein shortly after his capture in Iraq in December 2003.

Imagine sitting across from Saddam Hussein every day for nearly seven straight months—slowly gaining his trust, getting him to spill secrets on everything from whether he gave the order to gas the Kurds (he did) to whether he really had weapons of mass destruction on the eve of war (he didn’t). All the while gathering information that would ultimately be used to prosecute the deposed dictator in an Iraqi court.

That was the job of FBI Special Agent George Piro, who told his story on the TV news program 60 Minutes in January 2008.

Soon after Saddam was pulled out of a spider hole on December 13, 2003, the CIA—knowing the former dictator would ultimately have to answer for his crimes against the Iraqi people—asked the FBI to debrief Hussein because of its respected work in gathering statements for court.

That’s when the Bureau turned to Piro, an experienced counterterrorism investigator who was born in Beirut and speaks Arabic fluently. Piro was supported by a team of CIA analysts, as well as FBI agents, intelligence analysts, language specialists, and a behavioral profiler.

Piro knew getting Saddam to talk wouldn’t be easy. He prepped by studying the former dictator’s life so he could better connect with Saddam and more easily determine if he was being honest. It worked: during the first interview on January 13, 2004, Piro talked with the dictator about his four novels and Iraqi history. Hussein was impressed and asked Piro to come back.

From that day forward, everything Piro did was designed to build an emotional bond with Saddam to get him to talk truthfully. To make Hussein dependent on him and him alone, Piro became responsible for virtually every aspect of the ex-ruler’s life, including his personal needs. He always treated Saddam with respect, knowing he would not respond to threats or tough tactics. As part of his plan, Piro also never told Hussein that he was an FBI field agent, instead letting him believe, for the sake of building credibility, that he was a high-level official who reported directly to the President.

It took time. Piro spent five to seven hours a day with Saddam for months, taking advantage of every small opportunity that presented itself, including listening to Hussein’s poetry. Eventually, Saddam began to open up.

Among Saddam’s revelations:

- Saddam misled the world into believing that he had weapons of mass destruction in the months leading up to the war because he feared another invasion by Iran, but he did fully intend to rebuild his WMD program.

- Saddam considered Usama bin Laden “a fanatic” and a threat who couldn’t be trusted.

- The former dictator admitted “initially miscalculating President Bush and President Bush’s intentions,” Piro said, thinking the war would be more like the shortened air campaign of the Gulf War.

- Saddam never used look-alikes or body doubles as widely believed, thinking no one could really play his part.

- Hussein made the decision to invade neighboring Kuwait in 1990 following an insulting comment by one of its emirs.

Piro was so successful at befriending Saddam that the former dictator was visibly moved when they said goodbye. “I saw him tear up,” Piro said during the television interview. And for the FBI, which gathered vital intelligence and evidence along the way, it was time well spent.