Historic Firearms Returned to Philadelphia Museum

FBI Philadelphia seeks help recovering more Revolutionary War relics

The FBI, along with partners from the Department of Justice and the Upper Merion Township Police Department (UMTPD) in Pennsylvania, recently helped recover stolen Revolutionary War-era U.S. firearms that were a part of a string of thefts in the 1960s and 1970s in and around Valley Forge Park. The items were returned during a repatriation ceremony held at the Museum of the American Revolution in Philadelphia. The recovered firearms were among a wider swath of items looted during these robberies, for which little evidence as to the perpetrators had been uncovered in the past.

"We were all committed to seeing justice—not just bringing the objects back home, but seeking a proper prosecution of those who perpetrated these crimes," said Special Agent Jake Archer, a member of the FBI’s Art Crime Team who worked this case for FBI Philadelphia.

The Bureau’s role in this investigation was multipronged, Archer said. "We brought our investigative labor, first and foremost," he explained. "Secondly, we brought our multijurisdictional apparatus where we could cover leads in other parts of the country in a fast and orderly fashion. As well, we brought forth our evidence-response capabilities and that art crime-specific knowledge of how these cases should be investigated, and how the objects should be cared for."

Since the investigation into these thefts started in 2009, three men—Michael Corbett, Scott Corbett, and Thomas Gavin— have admitted taking items from the park and from the Valley Forge Historical Society located within Washington Memorial Chapel and helped investigators locate stolen items.

But the whereabouts of 10 additional items that these men, and perhaps other individuals, were involved in looting—from Valley Forge Park and elsewhere—remain unknown. Now, FBI Philadelphia and our partners are seeking the public’s help in tracking them down.

"We were all committed to seeing justice—not just bringing the objects back home, but seeking a proper prosecution of those who perpetrated these crimes."

Jake Archer, special agent, FBI Philadelphia

(From left to right) Assistant U.S. Attorney K.T. Newton of the U.S. Attorney's Office for the Eastern District of Pennsylvania, FBI Philadelphia Special Agent Jake Archer, Detective Andy Rathfon of the Upper Merion Township Police Department in Pennsylvania, Museum of the American Revolution President and CEO Scott Stephenson, and Upper Merion Township Police Detective Brendan Dougherty pose alongside Revolutionary War-era firearms they collectively helped recover. The photo was captured in January 2024 at the museum in Philadelphia.

In January 2009, a senior citizen visited a police station in Upper Merion Township, Pennsylvania—about 40 minutes outside of Philadelphia—to report that he’d spotted a stolen gun at an area antique show.

The tipster told UMTPD Detectives Andy Rathfon and Brendan Dougherty that the firearm had been taken from a museum located within Washington Memorial Chapel in Valley Forge in the 1960s or 1970s.

"Having not been born at the time, I didn’t know what he was talking about and had never heard any stories about these break-ins," Rathfon recalled. So, he thanked the tipster and did more digging.

Rathfon and Dougherty soon discovered that case files for minor crimes from that era would’ve already been discarded, and that no departmental records about burglaries at the historical site existed. Nonetheless, he and fellow UMTPD Detective Brendan Dougherty contacted the Valley Forge Historical Society—the organization that had administered the museum to learn more.

They soon found out the Valley Forge Historical Society had dissolved—but it had passed its collection and archives to a group that was attempting to build a museum dedicated to the American Revolution.

So, they met with the head of that organization’s curatorial team—Dr. Scott Stephenson, who now serves as president and CEO of the Museum of the American Revolution in Philadelphia—to see if they could lend their expertise to the budding investigation.

The meeting filled in the historical blanks the detectives needed.

The tipster’s hunch had been wrong: The firearm he’d spotted was never part of the Valley Forge Historical Society’s collection. But he was right about the break-ins at the historical park. As it turned out, there’d been three separate incidents over the course of approximately a decade, all of them still unsolved.

The detectives worked with Stephenson’s staff to compile a list of items believed to have been stolen from the Valley Forge Park and the Historical Society, along with descriptions and photos of the items.

A Museum of the American Revolution employee handles two firearms recovered during an art crime investigation conducted by FBI Philadelphia and our local law enforcement partners, with help from the museum and the U.S. Attorney's Office for the Eastern District of Pennsylvania. Members of the Royal Highland Regiment, part of the British Army sent to suppress the American rebellion, carried these steel pistols.

Their next task was determining who might’ve been responsible for the thefts.

“So, we started: Two detectives with a diaper box filled with files that Scott Stephenson and the Museum of the American Revolution were generous enough to give us,” Rathfon said.

The detectives traveled to multiple states to interview anyone who may have information. The more people they interviewed, though, the more they realized the case required outside resources and expertise to solve.

At this point, they had the name of one potential perpetrator—Michael Corbett. But an outreach attempt failed, and he declined to speak with detectives or to accept immunity in the case, explained Assistant U.S. Attorney K.T. Newton, who handled the case for the U.S. Attorney’s Office for the Eastern District of Pennsylvania.

Since the detectives didn’t have the out-of-state jurisdiction needed to investigate—Michael Corbett lived in Delaware—they spoke with Corbett’s brother, Scott.

After receiving immunity in the case, Scott Corbett told authorities that his brother had stolen multiple firearms from multiple museums and that he himself had participated in some of those thefts, too. Scott Corbett suspected that his brother either had the items in his possession or was storing them in a safe deposit box.

At this juncture, the detectives approached the FBI Art Crime Team and the U.S. Attorney’s Office about collaborating on the investigation, especially since the teamwork would solve their jurisdictional hurdles.

The FBI Art Crime Team generally investigates three major types of violations: theft, frauds and forgeries, and the illicit trafficking of cultural property. “Detectives Dougherty and Rathfon had done such a great job, already getting this case underway, and once we realized that this was certainly a multi-jurisdictional matter involving many, many important pieces of American history, we realized that we had to join in and act,” explained Special Agent Archer.

A federal warrant was obtained to search Michael Corbett’s Delaware residence. And while they found multiple firearms, none of them were the stolen ones the authorities had been searching for.

"Detectives Dougherty and Rathfon had done such a great job, already getting this case underway, and once we realized that this was certainly a multi-jurisdictional matter involving many, many important pieces of American history, we realized that we had to join in and act."

Jake Archer, special agent, FBI Philadelphia

A Museum of the American Revolution employee points out a detail of the brass inlay of a Revolutionary War-era musket that was recovered as part of a joint art crime investigation by FBI Philadelphia and our law enforcement partners, with significant assistance from the U.S. Attorney's Office for the Eastern District of Pennsylvania and the Museum of the American Revolution. A Massachusetts gunsmith manufactured the musket in 1775, and it was likely used in the earliest battles of the Revolutionary War.

Now, investigators had to determine what these items were and where they had been stolen from.

Some of these answers came from Scott Corbett, AUSA Newton said. “He had a very good memory and could tell us where Michael had stolen some of the firearms,” she noted.

The investigative team also traveled to Cody, Wyoming, to attend a national museum curator’s meeting to see if any experts could help identify these mystery items.

“It turns out Michael stole these items from museums from Massachusetts to as far south as Mississippi,” Newton said. "A lot of them were stolen from Pennsylvania. We believe he was responsible for two of the thefts at Valley Forge. He was also responsible for a theft at the U.S. Army War College Museum in Carlisle, Pennsylvania. So, we were able to identify some of these firearms.”

Based on the evidence at hand, AUSA Newton explained, “We couldn't charge him with the thefts, but what we could charge him with was possession of stolen property that had been transported interstate because he's in Delaware.”

Michael Corbett was indicted and pleaded guilty. As part of his plea, he agreed to help recover some of the items that the investigators were initially looking for when they searched his Delaware residence.

“Leads in the Corbett case took the FBI Art Crime Team as far west as San Francisco,” Archer added.

Coincidentally, during the investigation, a concerned collector called Dr. Stephenson because he believed he might’ve accidentally purchased a stolen rifle.

The collector initially purchased the gun from a man named Thomas Gavin, believing it to be a copy of a famous rifle built by Moravian gunsmith John Christian Oerter. But the more he researched, the more he suspected he had the genuine article. The collector turned the rifle over to the authorities.

Thomas Gavin turned out to be “a significant museum thief” in his own right, having robbed items from the Valley Forge Park, the Philadelphia Museum of Art, the Academy of Natural Sciences of Drexel University, and additional museums in the greater Philadelphia area. “But he too cooperated and told us what he had stolen,” AUSA Newton said.

“We had to then stop, solve that case in order to figure out who stole what from where, in order to then pick the Corbett case back up and bring it home,” Archer recalled of the Gavin section of the overall investigation. “So, it was staggeringly complex across space and time and material.”

But just like in Corbett’s case, investigators are still searching for items that Gavin stole, including a rifle that was once owned by naturalist John James Audubon.

Even though the investigators’ work is ongoing, the impact of the partnership and the recovery of the artifacts cannot be overstated.

“With the 250th anniversary of the American Revolution coming up,” said James Taub, an associate curator at the museum, “the teamwork and partnership between local police and the FBI have given us in Philadelphia and the historical community at large a really strong opportunity to reach people in ways that we haven't before, through objects that people of my generation haven't seen and that previous generations might not have seen since before the 200th anniversary of the American Revolution.”

Dr. Stephenson echoed that sentiment, noting that “for us, as educator- and preservation-oriented institutions, these objects are irreplaceable.”

Stephenson says the museum’s work isn’t done. “It may be that the person who stole an object say 50 years ago may have passed away long ago. In many cases, families may have things that they don't realize where they came from, how they came into that collection, or things that were sold and passed around.”

For this reason, he said, the museum is reexamining how it describes the missing objects, to highlight any valuable details that might spark someone’s memory. The museum is also spreading the word about the stolen items to antique enthusiasts and collectors.

"The fact is, the vast majority of people want to do the right thing,” he said.

But the FBI stands ready to investigate anyone who knowingly holds onto looted artifacts.

“Ultimately,” said Special Agent Archer, “people who know that they are in possession of these stolen items and do the wrong thing, we certainly are prepared to investigate.”

"With the 250th anniversary of the American Revolution coming up, the teamwork and partnership between local police and the FBI have given us in Philadelphia and the historical community at large a really strong opportunity to reach people in ways that we haven't before, through objects that people of my generation haven't seen and that previous generations might not have seen since before the 200th anniversary of the American Revolution."

James Taub, associate curator, Museum of the American Revolution

The Missing Pieces

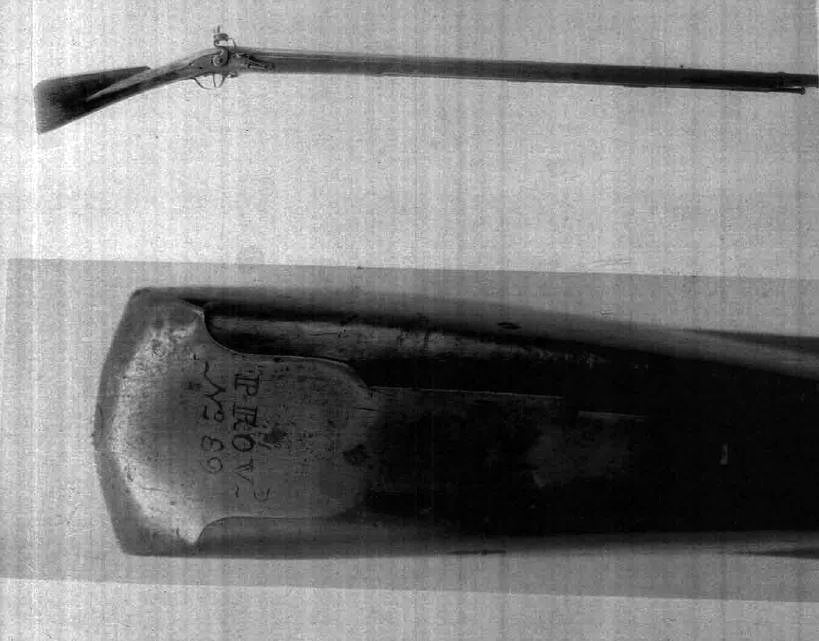

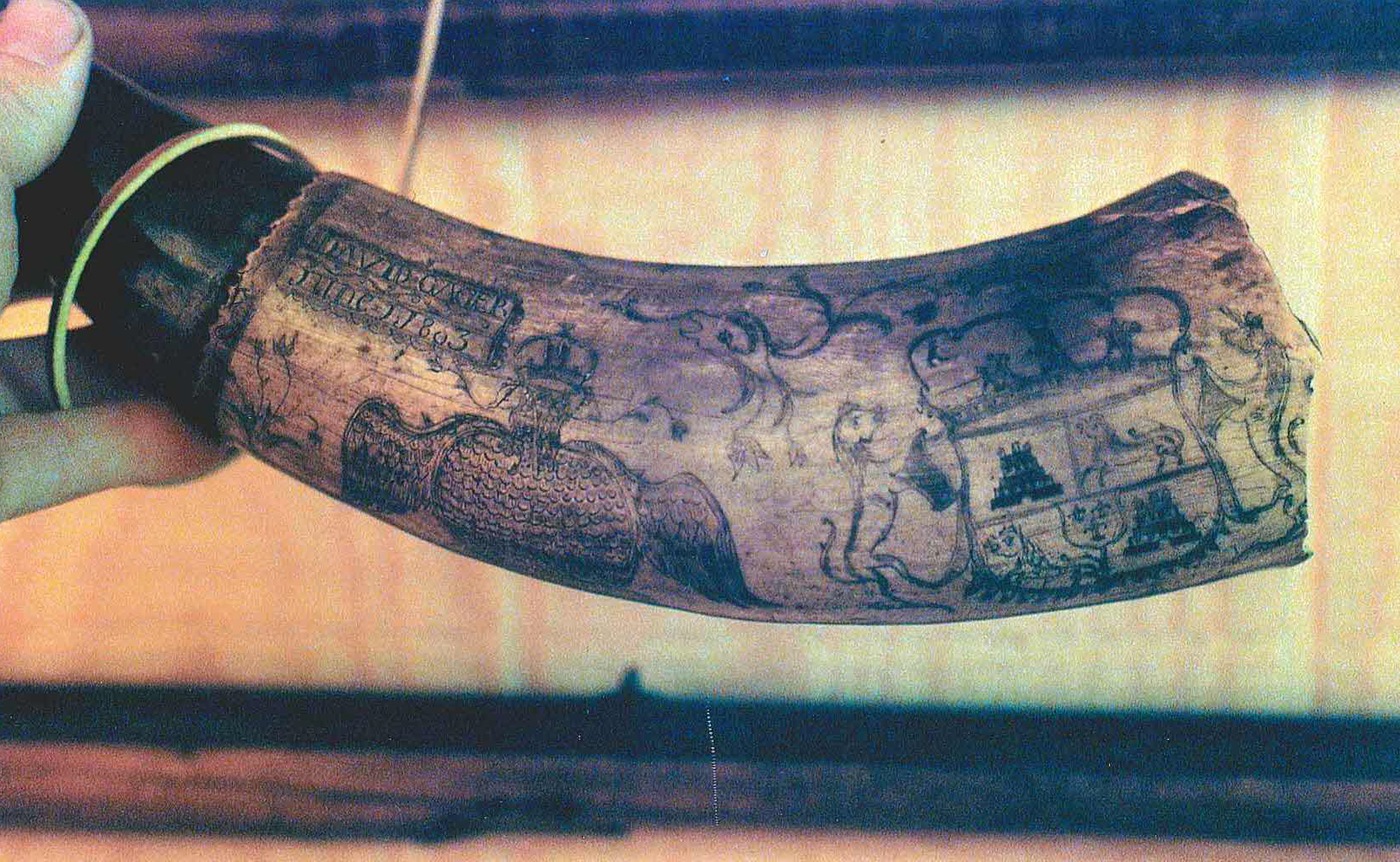

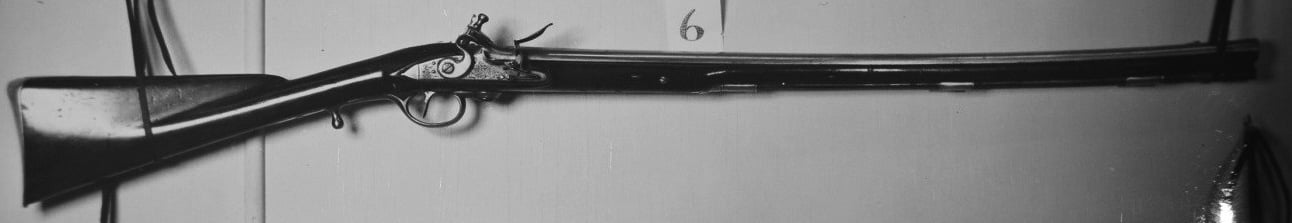

The FBI and our partners are still searching for four Revolutionary War-era firearms that were stolen from Valley Forge on October 24, 1968. Law enforcement is also searching for six additional items that were looted from different locations in Pennsylvania and New York.

Photos and/or descriptions of the 10 items are featured below. Click on the images below to view them in high resolution and read detailed descriptions of each item.

If you recognize any of the items, you should contact the FBI by calling 1-800-CALL-FBI (1-800-225-5324) or by visiting tips.fbi.gov. You can submit tips anonymously.

Six of the 10 items aren't pictured above, but also remain missing:

- American “Kentucky” musket

- This item was stolen from Valley Forge on October 24, 1968.

- This gun’s lock was created by James Golcher.

- Its patchbox is engraved with text reading “Presented by J. Kahn to President Geo. Washington, Mount Verson, Virginia – July 4, 1790.”

- Its octagonal barrel features engraving reading “J * Phil Py”—also listed as “J * Phil Pa.”

- The .55 caliber musket is 50 inches long, its barrel is 42.5 inches long, and its lock is 4 inches long.

- It has a curly maple stock and a plain wood ramrod.

- Its trigger guard, butt plate, and patchbox are all made of brass.

- John James Audubon shotgun

- This 12-or 16-gauge double-hammer, double-barreled shotgun once belonged to John James Audubon.

- The gun was stolen from the Academy of Natural Sciences of Drexel University in March 1972.

- It may have been sold at auction after the year 2000.

- The gun is 4.5 feet long.

- Smaller Schimmel eagle

- This carving was created by Wilhem Schimmel.

- This item was stolen from the York County Historical Society in Pennsylvania in January 1979.

- It may have later been sold at auction after April 1998.

- The carving has a 10-inch wingspan and stands 6.5 inches tall.

- It’s painted brown with white and black spots.

- The item is missing a small piece of wood on its cross-hatched head feathers.

- Larger Schimmel eagle

- This carving was created by Wilhem Schimmel.

- This item was stolen from the Reading Public Museum in Reading, Pennsylvania, in February 1979.

- It may have been sold at auction after April 1998.

- The carving has a wingspan of 17 inches and stands 9.5 inches tall.

- It’s painted black and has a cross-hatched carved body. It also has a green base and pastel yellow and orange paint over its wings.

- The item is missing wood on the tip of its head and feathers.

- Carved powder horn dated 1776 with deer and Native American scene

- This powder horn was stolen from the Old Stone Fort Museum in Schoharie, New York, in June 1971.

- It’s golden colored, about 13.5 inches long, and has a flat pine butt.

- The powder horn features a “CDM” monogram and “1776” above the drawing of a snake and the initials “JW” above a drawing of a buck with antlers.

- 1690 English oak Bible box

- This box was stolen from the Haverford Township Historical Society in Pennsylvania on April 14, 1979.

- The Bible box is made of oak wood.

- The date “1690” is carved on its front panel.