FBI Returns 16th-Century Letter from Spanish Conquistador to Mexican Government

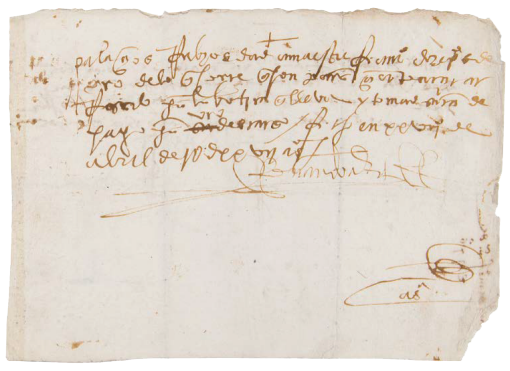

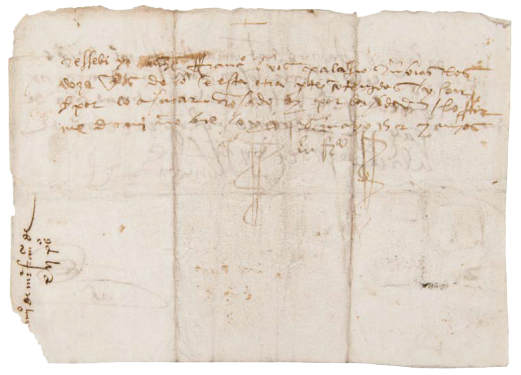

These photos show the front and back of a document signed by Spanish conquistador Hernán Cortés. The FBI repatriated the document to the Mexican government on July 19, 2023. Photo credit: FBI Boston

On July 19, the FBI returned a letter signed by Spanish conquistador Hernán Cortés to the government of Mexico. An investigation by the FBI Boston Division in collaboration with our legal attaché office in Mexico City and our international partners made the repatriation possible.

"We are incredibly honored to be able to assist in the return of this national treasure to the people of Mexico," said Christopher DiMenna, acting special agent in charge of the FBI Boston Division. "This manuscript, which is nearly five centuries old, preserves an important part of Mexico’s history and reflects the FBI’s ongoing commitment to protect cultural heritage, not only in the United States but around the world. The recovery of this priceless artifact is a direct result of our close and ongoing collaboration with the government of Mexico, and we are very thankful for their partnership.”

According to Supervisory Special Agent Kristin Koch, who manages the FBI’s Art Crime Program and led the FBI Boston Division’s investigation, the letter dates back to April 1527. It was signed by Cortés, whose large-scale expedition from Spain to Mexico about eight years earlier eventually led to the downfall of the Aztec Empire.

“The document itself is a payment order that he signed authorizing the purchase of rose sugar for the pharmacy in exchange for 12 gold pesos,” Koch said.

The Disappearing Letter

The letter was originally in the possession of Mexico’s national archives, formally known as El Archivo General de la Nación, Koch said. However, she explained it was among a batch of 15 historic documents—all signed by the Spanish explorer—that were looted from the institution "sometime in the late '80s or early '90s."

The letter was rediscovered at a Massachusetts-based auction house in 2022, decades after it had gone missing. After the company’s website put the letter up for auction, a representative of Mexico’s national archives reached out to FBI for help.

According to Koch, neither the FBI nor the Mexican government know when or how the document was stolen, nor how it made its way onto American soil. “But we do know that it ended up in an auction house in California in the early '90s, and it moved through several different hands until it reached the person that consigned it to the auction house in Massachusetts,” Koch said.

"This manuscript, which is nearly five centuries old, preserves an important part of Mexico’s history and reflects the FBI’s ongoing commitment to protect cultural heritage, not only in the United States but around the world.”

Acting Special Agent in Charge Christopher DiMenna, FBI Boston Division

Koch said the FBI authenticated the artifact through a process known as the mutual legal assistance treaty process, which allows “law enforcement authorities and prosecutors to obtain evidence, information, and testimony abroad in a form admissible in the courts of the Requesting State,” according to the Department of Justice.

From left to right: FBI Supervisory Special Agent Angel Catalan of Legat Mexico City; U.S. Ambassador to Mexico Ken Salazar; Dr. Carlos Enrique Ruiz Abreu, director general del Archivo General de la Nación; Lic. Miguel Ángel Méndez Buenos Aires, coordinador de asuntos internacionales y agregadurías de la Fiscalía General de la Republica; Mtro. Alejandro Celorio Alcántara, consultor jurídico de la Secretaría de Relaciones Exteriores; and Manuel Zepeda, director general de comunicación social de la Secretaria de Cultura pose for a photo at a repatriation ceremony in Mexico on July 19, 2023. During the ceremony, the FBI repatriated a document signed by Spanish conquistador Hernán Cortés to the government of Mexico. Photo credit: U.S. State Department

"Through the mutual legal assistance treaty process, the Mexican government provided us with official documentation outlining exactly why they believed that this document belonged to them,” Koch explained.

The Mexican government didn’t have a photograph of the letter but knew its specific dimensions, as well as information about the letter’s exact verbiage. “That gave us enough probable cause to obtain a seizure warrant to take the document from the auction house and bring it into our custody,” Koch said.

When the FBI seizes an artifact, the Bureau’s priority becomes establishing provenance—or an item’s origin—as well as determining how it arrived at its new location, Koch explained. In this case, FBI Boston invited personnel from Mexico’s national archives to Massachusetts to determine the letter’s authenticity via an in-person examination.

That analysis proved that the letter was genuine, and the FBI investigation determined that neither the person who put the letter up for auction, nor its previous owner, had known it was stolen. The Bureau then began the process of repatriating the artifact to the Mexican government.

How Repatriation Works

While the legal process behind a cultural repatriation can be complex, in this case, it essentially consisted of two phases.

The first phase was civil forfeiture—or the process by which a court deems an item official property of the United States government.

The second phase was a petition of remission. This gives the U.S. government permission to return an artifact to a foreign government. After a defined waiting period—designed to let people with legal claims to an artifact appeal the civil forfeiture—passes, the petition of remission is granted, and the repatriation can proceed.

At that point, the FBI can organize an artifact’s return to its country of origin.

“In this case, I hand-carried the object with me and was met at the airport by the Mexican authorities and the legal attaché,” Koch recalled. “In other instances, if the objects are very large, the case agents work with both fine-art shipping companies to have the items properly crated and shipped and with the local U.S. embassy or consulate to have those shipments made into diplomatic pouches to get those items returned to the country.”

From start to finish, the repatriation process can take years. But in the case of Cortés letter, Koch said, it took just over 13 months.

“I want to thank our colleagues at the Archivo General de la Nacion [Mexican National Archives], the Fiscalia General de la Republica [Mexican Federal Prosecutor’s Office], and the Department of Justice for the swift actions taken on this case to bring home an invaluable piece of Mexican history,” said Supervisory Special Agent Angel Catalan, who leads the FBI legal attaché in Mexico City. "The FBI will continue to collaborate with Mexican entities to identify, trace, and repatriate other items of immeasurable value that belong to Mexico's historical and cultural patrimony.”

“Mexico’s General Archive is grateful to the Federal Bureau of Investigation for the assistance, coordination, dedication, and effort they showed in defending the interests of Mexico's national memory, which resulted in the repatriation of the payment order signed by Hernán Cortes in 1527," said Dr. Carlos Enrique Ruiz Abreu, director general del Archivo General de la Nación. "I am sure that by working together, the United States and Mexican authorities, we will continue protecting the historical legacy of our peoples, acting as authentic guardians of their cultural heritage.”

Recovering the Remaining Documents

According to Koch, 14 other documents signed by Cortés are still missing.

If you are within the United States and have any information about the other documents’ whereabouts, submit a tip to the FBI by calling 1-800-CALL-FBI (1-800-225-5324) or visiting tips.fbi.gov.

"The FBI will continue to collaborate with Mexican entities to identify, trace, and repatriate other items of immeasurable value that belong to Mexico's historical and cultural patrimony.”

Supervisory Special Agent Angel Catalan, Legat Mexico City