SWAT at 50

FBI tactical teams evolve to meet threats

In early 1973, the FBI dispatched agents from across the country to Wounded Knee, South Dakota, where followers of the American Indian Movement staged a monthslong occupation of the Native American town on the Pine Ridge Reservation.

Agents set up roadblocks to isolate the protesters but discovered quickly how woefully unprepared they were for the violent, prolonged occupation. For starters, many agents were lawyers and accountants and had never managed a traffic stop, let alone a roadblock. Some arrived on the frozen windswept hills in their typical suits and wingtips.

The agents were armed but severely outgunned. Some found themselves pinned down by enemy fire until they could be rescued.

The 71-day occupation was a catalyst for development of the FBI’s Special Weapons and Tactics—or SWAT—program 50 years ago. Agents who were at Wounded Knee said it was a clarifying moment. Retired Special Agent Jim Huggins, a Marine Corps veteran assigned to the Minneapolis Field Office, which covers the Pine Ridge tribal lands, remembers it vividly.

"This was a really new experience, and we were not equipped for it, uniform-wise or clothing-wise or weapon-wise," Huggins said, recalling the nightly exchanges of gunfire with the occupiers. "It was totally foreign to anything we've done before. We were kind of learning as we went along. It was a very dangerous situation and nothing we'd ever prepared for."

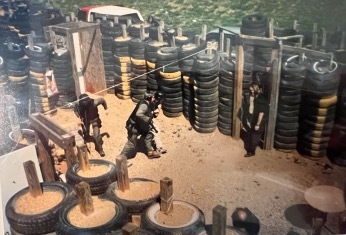

FBI SWAT exercises and equipment have evolved over the years. As shown, the team's "shooting house" at the FBI Training Academy in Quantico, Virginia, was a maze of old tires and beams in 1991. Today, it is fully enclosed and includes movable walls that can be configured to help SWAT teams train for specific conditions and operations. The facility allows teams to conduct live-fire training exercises to enhance their shooting and tactical skills.

Retired Special Agent Jim Horn, who earned a Silver Star in Vietnam in 1969 before joining the Bureau the following year, was there, too. He was assigned to the Denver Field Office when he deployed to South Dakota.

"It just wasn't very professional,” Horn recalled. “And we told them we were uncomfortable with it. Those of us who had a background of combat in Vietnam and police work in tough places were uncomfortable with that. We needed to be better at responding to things like that. It wasn't that much longer that they said, 'We're going to have a SWAT program.'"

In the summer of 1973, six field offices established SWAT teams of five members. The teams went to Quantico to train for a few weeks with the FBI Firearms Training Unit and also spent some time with military Special Forces.

Ongoing training at the home field offices was more limited in the early days as skeptical supervisors worried that training hours would cut into case work. Then, as now, an agent’s SWAT commitments are considered a "collateral duty," meaning they still have to manage all their cases in addition to deployments that can happen at any time.

"We had no equipment, we had no special weapons, we had no uniforms," recalled Tase Bailey, a former Marine who joined the Bureau as an agent in 1969 and worked out of the Washington Field Office. "We basically scrounged for whatever we had."

Then, SWAT started getting call-outs for airline hijackings, hostage-takings, and unique situations requiring special weapons and tactics (SWAT). Seeing the need, more field offices established teams and formalized training for breachers, assaulters, snipers, medics, and bomb technicians.

Retired Special Agent Dave Kirchner, a former SWAT team leader in Chicago, said it was gratifying to see how FBI supervisors at active crime scenes responded when his team arrived to assist. "They leaned on us completely," he said.

"We had no equipment, we had no special weapons, we had no uniforms. We basically scrounged for whatever we had."

Tase Bailey, special agent from 1969 to 1994, and member of original SWAT team, Spider One

In Their Own Words

Retired members of the FBI's SWAT program, including operators on the original SWAT teams (Spider One) in 1973, share recollection of the tactical program's early days.

Tase Bailey joined the FBI in 1969 and served in St. Louis and Washington, D.C., before working in the Firearms Training Unit at the FBI Training Academy. He was on one of the original SWAT teams in 1973 and retired out of the Dallas Field Office in 1994. Transcript

Kenneth Parkerson joined the FBI in 1966 as a night clerk in San Diego and became a special agent in 1971, working in Phoenix, Denver, and Miami. The former Navy corpsman was a member of the original FBI SWAT team in 1973. He retired from the Miami Division in 1996. Transcript

Steve Tidwell joined the FBI as a special agent in the Dallas Field Office in 1983, later rising to assistant director in charge of the Los Angeles Field Office and executive assistant director of the Bureau’s Criminal, Cyber, Response, and Services Branch (CCRSB) before retiring in 2009. Transcript

Today, the FBI has SWAT team members across all 56 field offices. Agents are selected for field offices SWAT teams and then go through a three-week course at the FBI Training Academy at Quantico to get certified. This standardized training means an agent stationed in San Juan, for example, will have the same skills and operating philosophy as an agent in New York City.

Paul Haertel has spent his career working with the SWAT program, from working an operator in the Lexington Field Office for eight years to serving as assistant director of the Bureau’s Critical Incident Response Group (CIRG), which oversees the FBI SWAT and Hostage Rescue Team (HRT) programs. He’s seen SWAT evolve from scrappy and under-resourced to what is now the largest tactical force in the United States. The teams have deployed more than 1,600 times in the past year alone.

“I've been fortunate to see the professionalization of the SWAT team,” he said at a recent meeting of the Society of Former Special Agents of the FBI. The annual conference's honorees included a handful of original SWAT team members, who called themselves Spider One—a reference to the spider-crawl that was part of their early training.

“We’re pushing all of our capabilities out to the field so that everybody’s trained in the same way so they can integrate operationally," said Brian Driscoll, a former FBI New York SWAT member who now commands the Bureau’s Hostage Rescue Team. “We are one tribe now instead of 56 silos of excellence, of 56 SWAT teams doing things 56 different ways. Everybody is on the same page and able to be integrated.”

"We are one tribe now instead of 56 silos of excellence. Everybody is on the same page and able to be integrated."

Brian Driscoll, commander, FBI Hostage Rescue Team

In Their Own Words

Jim Horn joined the FBI in 1970 as a special agent and retired in 1996. A Silver Star recipient for his heroic service during the Vietnam War as a Marine Corps officer, Horn was a member of one of the Bureau’s original SWAT teams in 1973. Transcript

Bob Foster joined the FBI in 1972 as a physical training assistant at the new Training Academy in Quantico, Virginia. He went on to become an HRT operator and team leader, and serve on SWAT in Louisville, Kentucky, before retiring in 2002. Transcript

Jim Huggins joined the FBI in 1967 as a special agent who served in the Minneapolis, Denver, and Louisville field offices. The former U.S. Marine was a member of one of the original SWAT teams in 1973 and retired in 1995. Transcript

Here's a brief look at the history of FBI SWAT:

1973

The first FBI SWAT teams receive training in advanced weaponry, rappelling, entries, orienteering, and scaling. Later teams train for specialized roles, such as snipers and assaulters.

1975

SWAT teams return to the Pine Ridge Reservation in South Dakota after Special Agents Jack Coler and Ronald Williams are killed while trying to serve a federal arrest warrant. The agents were shot at close range by a .223-type bullet. Witnesses tied Leonard Peltier—a fugitive who travelled to the reservation—to the weapon, an AR-15. He was convicted of two counts of first-degree murder in 1977 and sentenced to life in prison.

1981

The FBI establishes the Special Operations and Research Unit in the Training Division to develop the FBI’s crisis-response capabilities. It unites SWAT training, crisis management, and negotiations. The researchers in the group begin publishing their findings and recommendations, not only in law enforcement publications, but also in psychology journals.

1983

With an eye to preventing a hostage incident like the one at the 1972 Munich Olympics, the FBI stands up the Hostage Rescue Team (HRT), a "super SWAT team," in time for the 1984 Olympics in Los Angeles.

In Their Own Words

Tom Linn-Lim joined the FBI as a special agent in 1976 and was a firearms instructor at the FBI Training Academy before moving to the Oklahoma City Field Office. There, he served on SWAT from 1990 until he retired in 2001. Transcript

Dave Kirchner joined the FBI as a special agent in 1980. He worked in Kansas City for eight months before moving to the Chicago Field Office, where he was a SWAT operator for 21 years before retiring in 2003. Transcript

Brian Jerome joined the FBI in 1979 as a special agent in the Miami Field Office. He spent his 32-year career there as a case agent—including three decades as a SWAT operator—before retiring in 2011. Transcript

1986

A manhunt for two violent bank robbers and murderers ends in a high-speed car chase and shootout that leaves Special Agents Ben Grogan and Jerry Dove dead, and five other agents wounded—three seriously. The Miami shootout, as it’s later called, is the bloodiest in FBI history. A subsequent Bureau study concludes FBI handguns are no match for easily available high-power weapons. Many upgrades are made to weapons, body armor, and training.

1987

Upwards of 125,00 Cubans migrate to the U.S. in 1980 during the Mariel boatlift. Several thousand are detained as inadmissible under immigration law or, later, for crimes committed on U.S. soil. To avoid deportation to Cuba in 1987, the Marielitos riot at federal facilities in Atlanta and Oakdale, Louisiana.

Hundreds of SWAT team members and HRT deploy to extremely volatile standoffs that includes rioters dousing hostages—guards and prison staff—with gasoline and threatening to set them on fire. Deep cooperation between tactical teams and negotiators results in negotiated resolutions for one of the FBI's largest-ever crisis-management mobilizations.

The original SWAT team operators, seen here in July 1973, came from six field offices (Albuquerque, Denver, Kansas City, Omaha, Phoenix and Washington Field Office) with each field office team consisting of five agents. Highlighted above are (from left) Roger DePue, Kenneth Parkerson, Jim Horn, Tase Bailey, Jim Huggins and D. Michael Griffin.

Early 90s

In 1992 and 1993, respectively, multiple SWAT teams respond to the 11-day Ruby Ridge and 51-day Waco standoffs, following unsuccessful arrest efforts by the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms, and Explosives. Neither is resolved without loss of life, including the lives of small children at Waco after the Branch Davidians set fire to the compound. It becomes a time of deep reevaluation at the FBI.

1994

As a result of Ruby Ridge and Waco, the FBI stands up the Critical Incident Response Group (CIRG) as the FBI’s preeminent response group. For the first time, all critical incident components are housed together and can coordinate rapidly: crisis managers, tactical teams, crisis negotiators, behavioral analysts, bomb techs and aviation, and surveillance and strategic information groups.

1996

The 81-day standoff with the Freemen of Montana, one of the longest in FBI history, unfolds under heavy international media scrutiny—and in the light of Waco. The Freemen are wanted for a host of white-collar crimes related to sovereign-citizen ideology, for refusing to vacate foreclosed land, and for threatening to kill local officials.

Able to bring CIRG capabilities to bear, FBI tactical teams, negotiators, and profilers work together and with other agencies to pressure the heavily armed group—including by eventually staging two armored personnel carriers, borrowed from the Las Vegas Police Department and stenciled with “FBI” in large letters, in plain sight of the compound. In ones and twos, the occupants exit the compound, with the last Freemen surrendering peacefully on June 13.

1997 and beyond

SWAT teams are critical to the FBI’s response to all major incidents in the U.S. and overseas when Americans are concerned, including the World Trade Center bombing in 1993, the Oklahoma City bombing two years later, the East Africa embassy bombings in 1998, and 9/11. SWAT teams are also part of all major special events, including the Olympics in Atlanta and Salt Lake City, and they are deployed in the aftermath of major hurricanes. Enhanced teams deploy with HRT and are embedded with the military on deployments during the global war on terror.

Today

Today SWAT is changing with the times. The CIRG National Tactical Training Unit (NTTU), which administers SWAT, is re-envisioning what it means to be selected for a team, to be an operator on a team, and to be part of the larger National Tactical Program.

The changing nature of SWAT demands it. Callouts surged to approximately 1,600 in 2022, operations are increasingly complex, and the potential for violence during a callout has risen significantly.

NTTU Unit Chief Dave Spies said, as a result, today’s SWAT teams operators must not only meet the physical and intellectual demands of the job but also the mental and emotional demands. “It’s raising an already high bar,” he said.

For this reason, many teams are taking a more holistic approach to the rigors of the job and maximizing performance by incorporating tactics taken directly from military operators and elite athletes.

They are also looking to increase diversity on teams—people who are capable of making the team but potentially never thought of SWAT as an option before.

“Diversity in everything is a strength,” Spies said. “We’re looking for a group of people who are like-minded in that they want to work together and solve the hardest problems of the FBI.”

Another push has been standardizing field office tryouts, which include firearms proficiency and physical challenges like running and climbing, as well as stamina exercises. Additionally, agents are evaluated on their ability to make decisions and exhibit good judgement under stress.

SWAT senior team leaders and NTTU have worked out the critical skills every team needs to test for, while leaving flexibility for teams to tailor to their own needs. In this way, they ensure as much national uniformity of teams as possible.

At the 50-year mark, SWAT is evolving, yet staying true to its roots. “The people who come to SWAT are always the same,” said NTTU Supervisory Special Agent Scott Mitchell. “They’re high-achieving, self-motivated individuals who are performance-driven and never give up.”

Spies agrees, adding that good SWAT operators have the “hard skills, like close-quarter battle and firearms, but also soft skills: loyalty, trustworthiness, and a good balance of drive and determination.”

HRT’s Brian Driscoll described SWAT much as the original team members—Spider One—would have described themselves.

"We’re looking for a group of people who are like-minded in that they want to work together and solve the hardest problems of the FBI."

Dave Spies, unit chief, National Tactical Training Unit

“We are a collection of selected individuals,” Driscoll said. “We're forged on diverse experience, sustained on a culture of mutual support and collective success, purpose-driven to win every fight we get into. And we do get in a lot of fights. What we do boils down to this: we solve problems. We solve the most complex, unpredictable, asymmetrical, and dangerous problems in law enforcement in a time-compressed environment.”

Retired SWAT agent and Tom Linn-Lim added that despite common perceptions, SWAT teams from day one have always had a straightforward goal.

“The goal is to resolve the dangerous situation and as peacefully as possible,” said Linn-Lim, who joined the Bureau in 1976 in Oklahoma before becoming a firearms instructor helping train SWAT operators. “A successful mission is when you bring it to conclusion without anyone getting hurt, to include us.”