Investigating Environmental Crimes: The Huntington Oil Spill

FBI, partners used groundbreaking techniques and technology in 2021 case

On October 3, 2021, a thick black sheen of oil reached the shores of Huntington Beach, California. It spanned nearly six nautical miles and reached as far south as San Diego. Over three days, 25,000 gallons of oil leaked from a pipeline eight miles offshore. As the beaches closed, city businesses lost money—and local wildlife sustained immeasurable damage.

While the San Pedro pipeline had begun leaking in October, the initial damage to the pipeline had occurred months earlier. The FBI, in partnership with the U.S. Attorney’s Office, the U.S. Coast Guard, the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management (BOEM), the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), and others, would use groundbreaking investigative techniques and advanced technology to successfully identify when the pipe had been ruptured and who was at fault and, ultimately, earn financial restitution to the affected victims.

Elly, operated by Beta Operating Company, a subsidiary of Amplify Energy Corporation, was built in 1980. She and her sister rig, Ellen, pump crude oil to shore via the 17.5-mile long San Pedro pipeline along the ocean floor. To protect it from the elements, the pipeline is wrapped in tar and encased in concrete.

When the oil spill occurred, the most plausible explanation for how it had happened became known as the "anchor strike" theory. It supposed that a cargo ship's anchor had struck and possibly dragged the pipeline out of alignment. The protective concrete would have been damaged or even broken off, allowing seawater to eventually corrode the pipe and cause the leak.

The Coast Guard was among the first U.S. agencies to investigate the spill. They sent a robotic-operated vehicle into the water and found one of the spots where a break had occurred and, nearby, chunks of the concrete encasement lying on the ocean floor.

By now, the FBI Los Angeles Field Office had gotten involved with the investigation. The FBI’s Underwater Search and Evidence Response Team (USERT) was brought in to review the Coast Guard’s footage. Ty Summers, the USERT team lead, watched their video, looking for any kind of evidence to use to build a case.

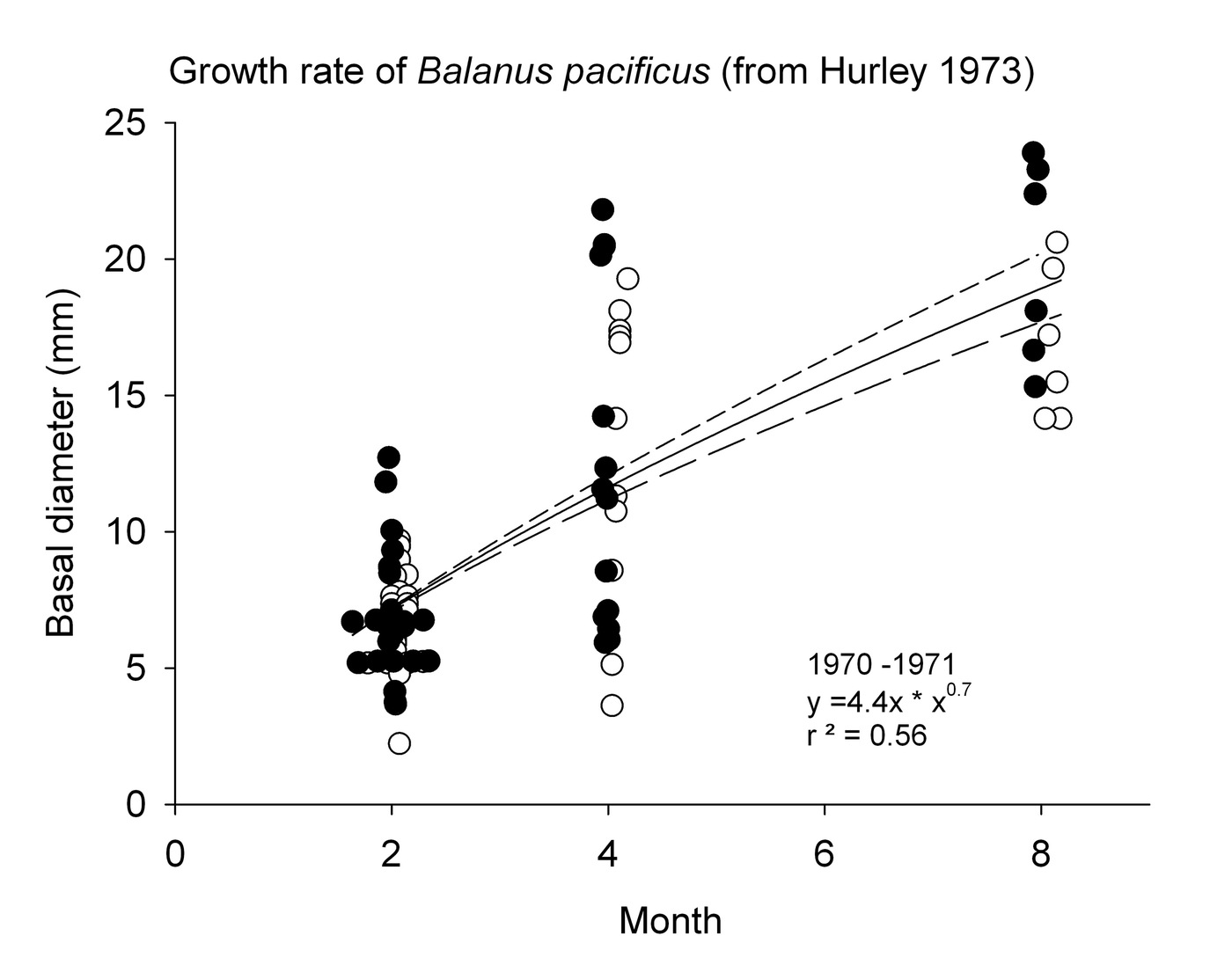

Summers noticed signs of marine life were present on the exposed part of the pipeline. Specifically, there were two invertebrate marine life forms, barnacles and tube worms. And they were seen in two obvious locations: on the concrete chunks that had broken off and on the exposed pipeline.

By contrasting the marine life on the pipe and on the concrete, the investigative team determined they could establish a timeline for when the pipe had broken. To do so, the FBI would need to conduct dives to collect samples of the marine life alongside BOEM.

"The federal diving community is very small," said Donna Schroeder, who, along with Susan Zaleski, is a marine biologist and research diver at the BOEM. Among their research areas, Zaleski and Schroeder study the impacts of manmade structures (like oil pipelines and wind farms) on the marine environment. In particular, they study the exact kind of marine life invertebrates Summers had seen on the video.

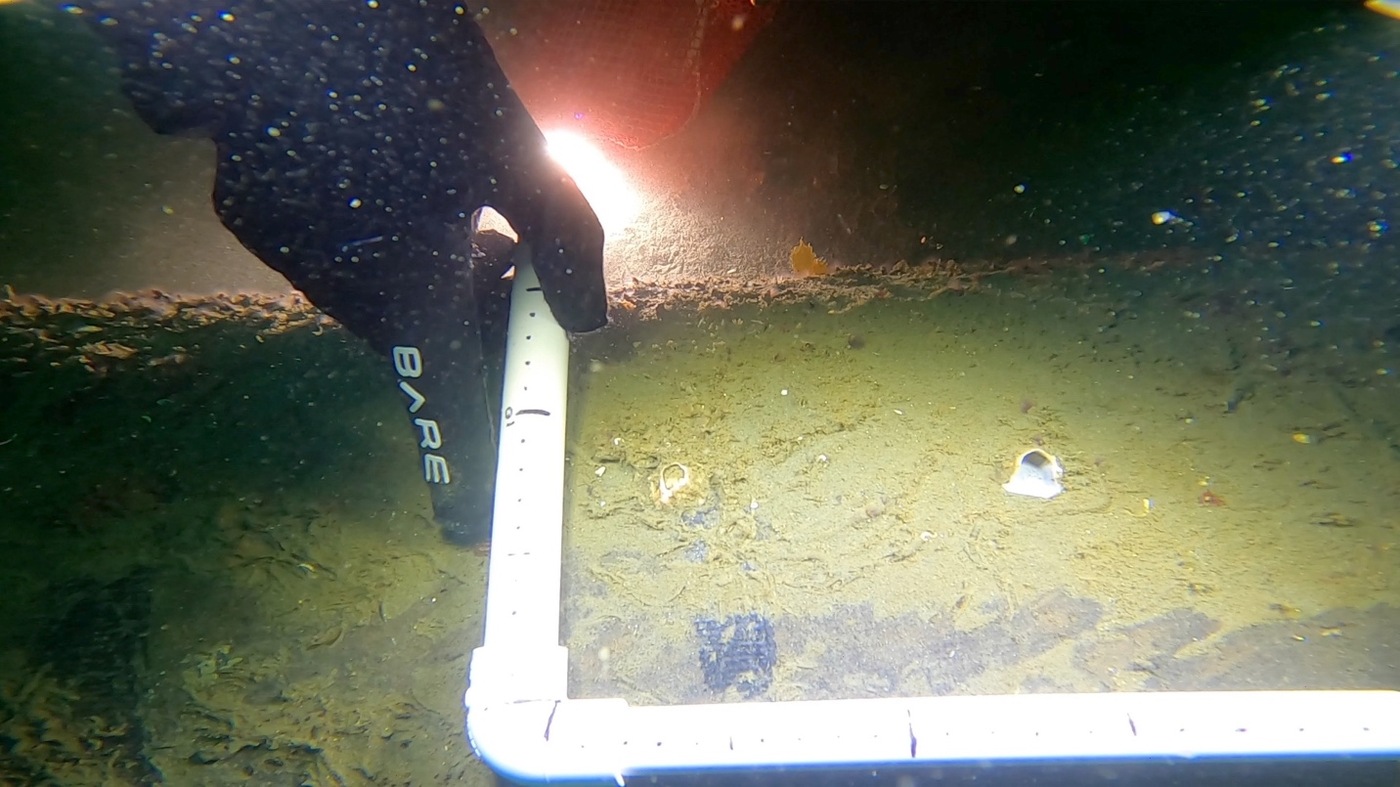

The BOEM divers partnered with USERT to go to the point of the break and collect samples of the marine life there. Zaleski and Schroeder had the expertise with the species being collected and USERT would support and observe them on the dive as evidence collectors. USERT’s presence would allow the FBI to attest that the evidence was collected appropriately. "It was a great experience to work with the USERT team," Schroeder tells of the experience. "They were very professional. It was a real highlight."

The dive needed to happen quickly. Amplify was eager to conduct their own research into the break and fix the damaged pipeline and the FBI couldn’t afford to stall. And at depths of over a hundred feet, the time of the dives was limited.

"It was a great experience to work with the USERT team."

Donna Schroeder, marine biologist and research diver, Bureau of Ocean Energy Management

Together, they conducted two dives. First was a reconnaissance dive. They visited the site to observe the conditions and what evidence could be collected. The information gathered would directly inform the dive plan for their second dive, during which they would collect samples.

The FBI worked with Dr. Mark Page, a marine biologist and researcher at the University of California, Santa Barbara. Using the information gathered from the reconnaissance dive, Dr. Page helped identify which samples should be collected and from where.

"The dive was really challenging because we were going in deep water," Zaleski explained about the 100-foot dive. "When you're down at that depth, we really only had 12 minutes of bottom time to get done all the tasks that we need.

"So, before you go down, you need a thorough dive plan as to what each person is going to do for the sampling, because we can communicate underwater only via hand signals. And so, we had a strategy and a plan for how we were going to sample before we got down there so that we wouldn't waste any seconds."

The dive was ultimately successful. The samples were collected and presented officially to the FBI. The next step would be to age them. For this, the FBI would once again consult Dr. Page.

The samples taken from the concrete showed how old the marine life in the area was. By comparing the type and sizes of the marine life to what was on the recently exposed concrete, and consulting scientific literature, Dr. Page proved that the break had happened at least eight months earlier.

Photos from Zaleski and Schroeder's dives showing the sample collection from the pipeline. Additionally, a part of Dr. Page's findings, which demonstrates the age of the samples found.

In January 2021, the Los Angeles Port, one of the country’s largest and busiest shipping hubs, had effectively become a parking lot. COVID-19 had significantly slowed shipping rates globally, and dozens of 150,000-ton cargo ships were backed up and anchored in tight proximity to one another, creating a dangerous situation with little room for error. One or more of these ships was suspected to have damaged the pipeline. But the FBI would need to collect more data to narrow the list of which ships it could have potentially been.

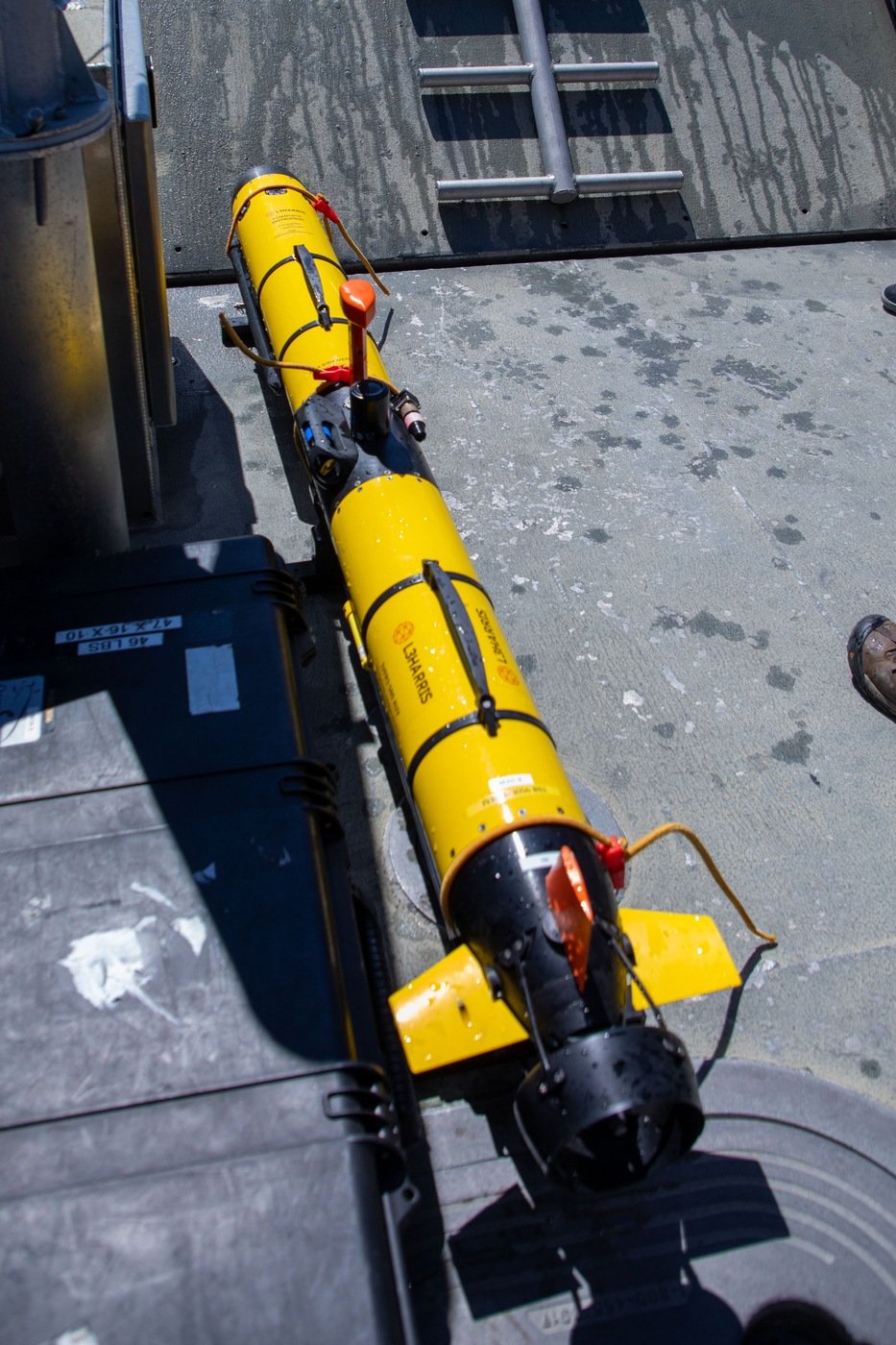

In addition to assisting in the sample collection, USERT also worked to map the impact site. At 100 feet down with little natural light and murky ocean environments, the human eye could not effectively observe the surrounding area.

To address this, the FBI used sidescan sonar. Deployed from a remotely operated vehicle, the sonar would be pinged repeatedly. The intent was to divide the area into grids and use multiple sidescan sonar launches to fill in the grids. Dozens of missions over time would yield data for the entire area.

There are several things one can infer from sonar data, including the time it takes the sound to return gives depth. And the strength of the return can tell you what kind of material the sound is reflecting off of. A weak signal indicates muddy, sedimentary ocean floor. Stronger signals can indicate rocky bottom or foreign objects such as metal and concrete.

Summers turned the raw sonar data into a picture of the ocean floor around the break site that showed a few key details. First, the pipeline indeed was out of alignment from where it should have been, another indication it had been dragged. Second, in the soft ocean floor were furrows—scars left by an anchor that had dragged across the ocean floor and ultimately had snagged on the San Pedro pipeline.

The FBI used sidescan sonar, seen here, to help provide data to map the ocean floor surrounding the break.

A sample of the sonar data provided back. The long horizontal rows show the path of the sidescan sonar. Each section was laid side-by-side to produce a larger image of the ocean floor at the break site.

Left: Susan Zaleski, a USERT diver, and Donna Schroeder pose for a photo in front of the FBI boat. Right: photos from the USERT and BOEM dives to investigate the pipelines.

To help interpret this data, the FBI turned to another contact provided by BOEM: Dr. Guy Cochrane, a research marine geophysicist with the U.S. Geological Survey. The FBI presented the sonar data to Dr. Cochrane for review, as well as wind data, tidal data, and ships' GPS data.

On January 25, 2021, eight months before the spill, a massive thunderstorm hit the shore. High winds and choppy seas took a toll on the cargo ships backed up there. In an effort to avoid a collision, ships dropped their anchors and engaged their engines in an attempt to stay in place. In spite of this, the winds blew two ships so strongly that their anchors were dragged—and ultimately hit the San Pedro pipeline.

Dr. Cochrane combined the automatic identification system (AIS) navigation data into a geographic information system and illustrated the activities of the ships relative to pipeline damage locations, anchor furrows in the seafloor, wind speed and direction, and substrate information. Analysis showed both ships—MCS Danit and the Beijing—went through similar activities at similar times.

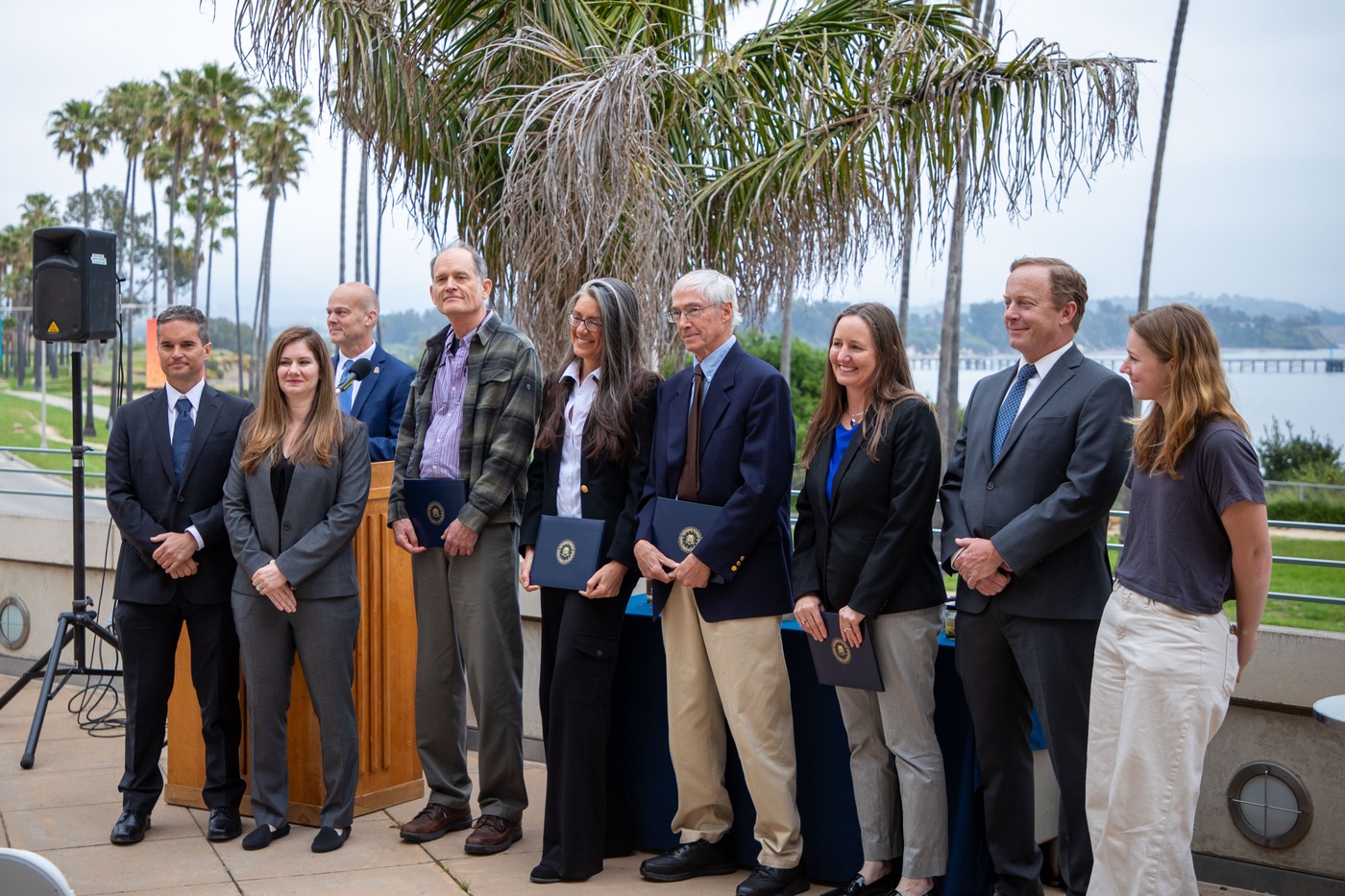

On April 19, 2024, in Santa Barbara, California, Susan Zaleski, Donna Schroeder, Dr. Guy Cochrane, and Dr. Mark Page all received FBI Director’s Awards for their participation in this case. From left to right, USERT lead Ty Summers, Special Agent Ketrin Adam, Assistant Agent in Charge Sean Haworth, Dr. Guy Cochrane, Donna Schroeder, Dr. Mark Page, Susan Zaleski, Assistant U.S. Attorney Matt O'Brien, and lab technician Makenna Colucci.

With the successful identification of the ships at fault, the FBI and U.S. attorney’s office pursued legal action within a year of the spill.

Amplify Energy Corporation was charged with negligent discharge of oil. Further investigations showed that Amplify did not take appropriate action when initial signs of the spill were first observed on October.

As a result of the investigation, Amplify and the vessels were charged a total of $210 million in civil and criminal penalties. Amplify was charged $12 million in criminal fees and an additional $5.9 million in clean up costs. Amplify and the vessels also agreed to pay $95 million to the victims at Huntington Beach affected by the spill.

By collaborating with government agencies and state and local partners, the FBI assisted in the expedient and successful prosecution. Dr. Cochrane said, "This kind of multidisciplinary approach to science and investigation, it’s really where it’s at."