Forging Papers to Sell Fake Art

Many Victims May Unknowingly Own Phony Works

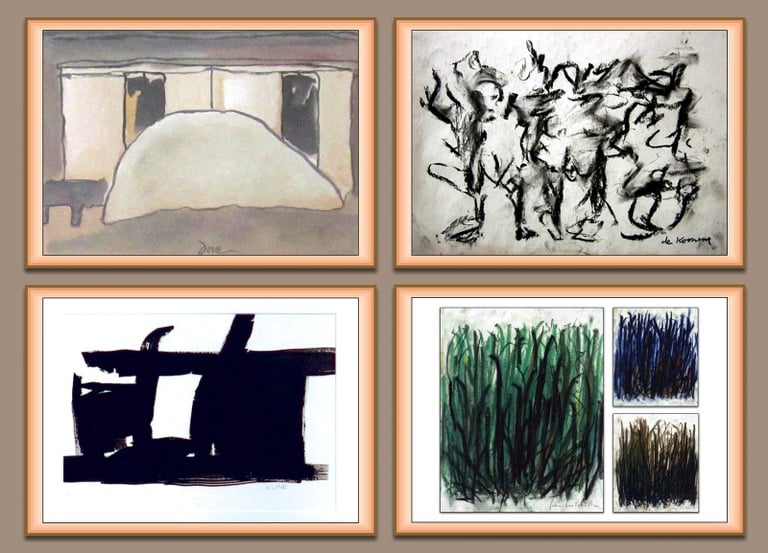

Eric Ian Hornak Spoutz offered fake works like these for sale, accompanied by forged paperwork to make them appear authentic. Spoutz offered works attributed to (clockwise from top left) American artists Arthur Dove, Willem de Kooning, Joan Mitchell, and Franz Kline.

Michigan art dealer Eric Ian Hornak Spoutz grew up in a family of artists. His namesake uncle, Ian Hornak, was famous among Hyperrealist and Photorealist painters, and his mother was a gifted painter as well.

Spoutz became an artist in his own right—a con artist peddling fakes. His specialty was forging the paperwork that he used as proof of authenticity to sell bogus works.

His deceit finally caught up to him on February 16, when he was sentenced in New York to 41 months in prison on one count of wire fraud for defrauding art collectors of $1.45 million. The judge also ordered Spoutz, 34, of Mount Clemens, Michigan, to forfeit the $1.45 million and to pay $154,100 in restitution.

Spoutz’s scam was straightforward but well executed. He contacted art galleries or auction houses and offered for sale previously unknown works by artists such as American abstract impressionists Willem de Kooning, Franz Kline, and Joan Mitchell. The art did not appear in any catalogs or collections of the artists’ known works, said Special Agent Christopher McKeogh from the FBI’s Art Crime Team in our New York Field Office.

“He was selling lower-level works by known artists,” explained McKeogh, who worked the case for more than three years with fellow agent Meridith Savona and forensic accountant Maria Font. “If it’s a direct copy of a real one, the real one is going to be out there and the fraud would be discovered.”

Before paying thousands of dollars for works of art, collectors and brokers want assurance the work is real—especially if the work is previously unknown, McKeogh said. Among other things, they look at the provenance—the paper history of an item that traces its ownership back to the original artist—for proof.

Spoutz, who also owned a legitimate art gallery, understood the value of provenance. He forged receipts, bills of sale, letters from dead attorneys, and other documents. Some of the letters dated back decades and looked authentic, referencing real people who worked at real galleries or law firms. Spoutz also used a vintage typewriter and old paper for his documentation.

The old typewriter turned out to be the smoking gun in the case. “We could tell all of these letters had been typed on the same typewriter,” McKeogh said. The type of a letter allegedly sent from a business in the 1950s matched the type in a letter allegedly sent by a firm in a different state three decades later. Spoutz also mistakenly added a ZIP Code to the letterhead of a firm on a letter dated four years before ZIP Codes were created.

Another red flag was that many of the people referenced in the letters were dead. And some of the addresses were in the middle of an intersection, or didn’t exist at all. “All these dead ends helped prove a fraud was being committed,” McKeogh said.

When marketing his fakes, Spoutz stopped just short of saying the works were authentic. “He tried to give himself an out and said they were ‘attributed to’ an artist,” McKeogh said.

Spoutz used sellers all over the country to move his forgeries, some of them fetching more than $30,000. “He looked for people that were not as familiar with a particular artist. Spoutz came across as very scholarly and knowledgeable,” McKeogh said.

He also used a number of aliases in the roughly 10 years he ran his scam, and he moved around, from Michigan to Florida to California. He changed the scam over time, selling the works of one artist, then switching to a different artist using a different alias. He was arrested in Los Angeles and charged in February 2016, and pleaded guilty to a single charge of wire fraud in June.

Spoutz produced the fake provenance, but not the fake art. “Spoutz was not known as an artist. He had a source he kept going back to,” McKeogh said. The FBI used experts in the field and artist foundations to determine the works Spoutz sold were forgeries.

Many of the fakes passed through auction houses in New York City, McKeogh said, and a suspicious victim eventually contacted the FBI. McKeogh inherited the case about three years ago, when another agent retired.

Although Spoutz has been sentenced, McKeogh and Savona do not believe they have seen the last of the fakes he peddled. The FBI recovered about 40 forgeries; there could be hundreds more that were sold to unsuspecting victims. “This is a case we’re going to be dealing with for years. Spoutz was a mill,” McKeogh said.

Protecting the integrity of America’s art—in all its forms—is a special priority for the FBI and our dedicated Art Crime Team. “It’s our heritage; it’s who we are. We have to protect it,” McKeogh says. “Fake art and fraud schemes like this damage that heritage.”

Did You Buy a Fake?

The New York Art Crime Team believes there may be more victims of Eric Ian Hornak Spoutz who unknowingly bought fake works. Spoutz forged documents using historical names such as the “Betty Parsons Gallery,” “Larry Larkin,” “Henry Hecht,” and “Julius or Jay Wolf.” His known aliases include “Robert Chad Smith” and “John Goodman.”

If you believe you are a victim and purchased a fraudulent painting, please call the New York Art Crime Team at (212) 384-1000 or submit a tip at tips.fbi.gov.

“He looked for people that were not as familiar with a particular artist. Spoutz came across as very scholarly and knowledgeable.”

Christopher McKeogh, special agent, FBI New York, Art Crime Team