The Hoover Legacy, 40 Years After

Part 3: Another Side of J. Edgar

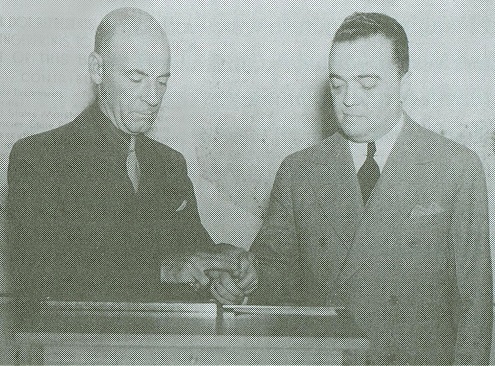

Courtney Ryley Cooper rolls J. Edgar Hoover’s fingerprints, circa 1936. National Archives photo

The mid-1930s were an important turning point for J. Edgar Hoover’s Bureau. It had just defeated a series of dangerous gangsters. Its agents were now heralded as “G-Men.” And it was no longer one of several indistinct “Divisions of Investigation.” In July 1935, it was given a new name to go with its rising success—the Federal Bureau of Investigation.

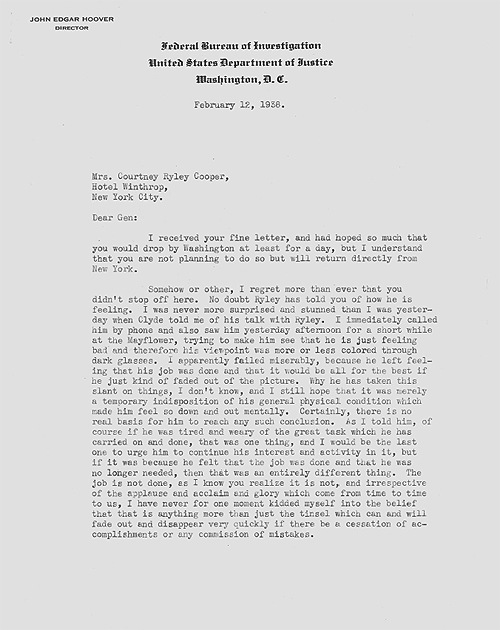

View 1938 letter from J. Edgar Hoover to Genevieve Cooper.

Still, the young FBI faced plenty of criticism, some justified and some not. During this time, it worked closely with the Department of Justice (Attorney General Homer Cummings was leading a “war on crime” publicity campaign with respected reporter Henry Suydam) and the news media to tell its story accurately and favorably.

In 1933, Hoover began working with Courtney Ryley Cooper. In the early 1930s, Cooper—a veteran author, reporter, and publicist—began writing about the problem of crime in the U.S. and the FBI’s growing role in addressing it, including a series of articles for American Magazine. His FBI-centered books included Ten Thousand Public Enemies (on the criminal underworld), Here’s to Crime (various criminal activities), and Designs in Scarlet (prostitution).

Hoover admired Cooper. The two shared an interest in denouncing the scourge of crime and a vision that the FBI was performing an important public service. As a result, Ryley Cooper (as he was known) came to be a good friend of J. Edgar and a key influence in shaping the Bureau’s public image during an often trying time.

Evidence of this relationship is seen in a February 1938 letter that Hoover sent to Cooper’s wife, Genevieve—or Gen, as Hoover called her. Ryley had just left D.C. after giving a talk at a joint session of the FBI National Academy and the current new agent training class. Hoover told Gen he found Ryley “feeling bad” and thought his viewpoint was “colored through dark glasses.” The Director says he tried unsuccessfully to cheer Ryley up.

In what remains of Hoover’s writings, the letter is unique. It shows a friendly and personal side of Hoover, who was genuinely concerned about an apparent streak of depression in his friend. The Director himself admits to being “terribly weary and terribly tired,” with “tremendous and almost overwhelming worries pressing in on me,” but still committed to carrying forward. He signed the letter “Jayee,” a nickname used by very few people in Hoover’s life, again suggesting his close ties to the Coopers.

It’s not clear what happened over the next several years. In 1940, Ryley Cooper began traveling in Mexico and California, digging up information for a story or series on Nazi propaganda and espionage in the United States.

Tragically, after returning to New York in September 1940, Ryley Cooper committed suicide in a hotel room. Initial press reports indicated that Mrs. Cooper thought Ryley might have been depressed on account of an FBI snub. There is no evidence of this, and Hoover thought it unlikely, noting that he hadn’t met with Cooper after he returned from his travels nor had he discussed his recent Nazi research with him. Although the 1938 letter hints Ryley’s issues with depression were longstanding, the mystery remains as to why he took his own life and what Hoover made of the loss of his friend.

The story of Cooper and Hoover is not well known, but it does shed important light on both Hoover’s personality and the FBI’s evolving image during a pivotal time in FBI history.