Civil Rights in the '60s

Part 2: Retired Investigators Reflect on 16th Street Baptist Church Bombing

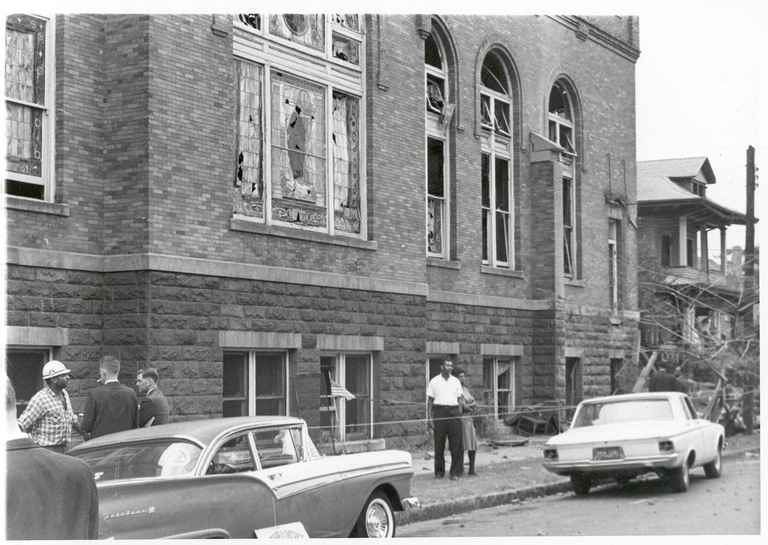

Investigators at the 16th Street Baptist Church after it was bombed on September, 15, 1963.

On September 15, 1963—50 years ago this Sunday—five young girls preparing for Sunday worship services were in the basement of the 16th Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, Alabama, when a bomb tore through the church’s east wall, killing four of them.

The blast at the African-American church—a popular meeting place for civil rights leaders like the Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr.—was a turning point in the civil rights movement. The killing of young innocents—Addie Mae Collins, Denice McNair, Carole Robertson, and Cynthia Wesley—drew national attention to Birmingham...a city some already called “Bombingham” because of its volatile pattern of racially motivated attacks.

The FBI sent dozens of agents to investigate, but reluctant witnesses and a lack of prosecutable evidence made it hard to bring the bombers to justice. It wasn’t until a decade later in 1977 that one of the bombers, Robert “Dynamite” Chambliss, was convicted for his role in the case, but evidence still suggested more conspirators. In the mid-‘90s FBI Birmingham Special Agent in Charge Rob Langford reopened the case, assigning senior agent Bill Fleming and recruiting Birmingham Police Department Sgt. Ben Herren to work it full time.

“It pretty much looked like an uphill battle,” said Herren, who is now retired and living in Birmingham. He and Fleming were initially reluctant to take the case, given that more than 100 potential witnesses had died in the decades since the bombing. In 1996, Herren recalled thinking it was the ultimate cold case. “But if we’re going to do it,” he said at the time, “we need to do it right, because this is the last time that it would be feasible to try to reinvestigate.”

For nearly 15 months, the two scoured the case files with a singular focus on finding new leads. “I didn’t read anything else about it,” Herren said. “I wanted the files to lead me through the investigation instead of me trying to lead the investigation.” The files led them back to familiar names from earlier probes.

They tracked down Bobby Cherry, a known Birmingham Ku Klux Klan member who had moved to Texas, and interviewed him for four hours. The exchange so incensed Cherry that he called a press conference to loudly proclaim his innocence. It made national news, and the FBI’s phones started ringing. “This was the best thing to happen to our investigation,” Fleming said, “because we started getting witnesses and people that were able to give us information.” The witness accounts would eventually implicate Cherry at trial.

They tracked down Bobby Cherry, a known Birmingham Ku Klux Klan member who had moved to Texas, and interviewed him for four hours. The exchange so incensed Cherry that he called a press conference to loudly proclaim his innocence. It made national news, and the FBI’s phones started ringing. “This was the best thing to happen to our investigation,” Fleming said, “because we started getting witnesses and people that were able to give us information.” The witness accounts would eventually implicate Cherry at trial.

As tips rolled in and more witnesses stepped forward, Fleming and Herren expanded their focus to Tommy Blanton, who was suspected in the early investigation—enough so that agents had planted listening devices at his home. Fleming tracked down the old reel-to-reel tapes, which revealed Blanton in scratchy audio explaining to his wife and another man the details of how the bomb plot unfolded.

Relying heavily on the tapes, a jury in 2001 needed only a couple hours to render a guilty verdict against Blanton on state murder charges. He was sentenced to life in prison, where he remains today. Cherry was convicted in 2002 for his role as a co-conspirator and sentenced to life in prison, where he died in 2004.

Fleming and Herren, who remain close friends today, have been lauded for their tireless work. But they are quick to credit others who stepped forward in the course of their investigation.

“If it was not for the people who read the paper and [saw] the TV spot—and all we had was the file—I don’t know that we would have ever accomplished anything,” Fleming said.

Both have said the investigation was the most rewarding case they ever worked. “You feel like you have done the job,” Herren said. “Even though it looked like a tremendous uphill battle, we finally got justice for the little girls.”

View files related to the Birmingham bombing investigation at the FBI Vault

Interviewing Witnesses

Many of the witnesses tracked down by Bill Fleming and Ben Herren were eager to talk. In one example, Herren described how one of Cherry’s granddaughters met them at the door and began talking even before introductions. “Oh my gosh, I’m glad y’all are investigating,” she said. “You ought to hear what he talks about at family reunions.”

Interviews with the suspects’ former associates were notably less fruitful, even with the passage of time. More than once the investigators sat in former Klan members’ living rooms marveling at the presence of a family Bible during their interviews. “I always kept thinking maybe one person—one who hadn’t cleared their conscience a little bit—would tell us what they know about it because they’re getting up in age, getting ready to meet their maker,” Herren said. That never happened.