A Byte Out of History

The Alger Hiss Story

The jury returned from its deliberations on January 21, 1950—63 years ago this month. The verdict? Guilty on two counts of perjury.

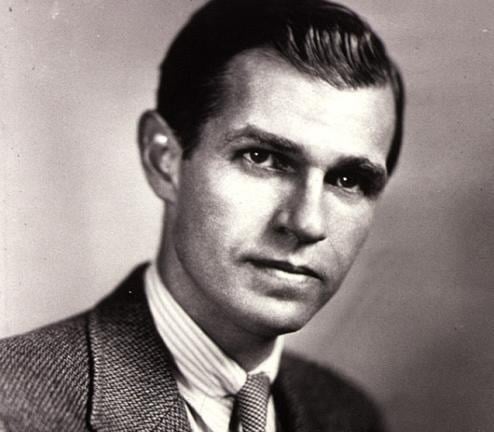

Alger Hiss, a well-educated and well-connected former government lawyer and State Department official who helped create the United Nations in the aftermath of World War II, was headed to prison in Atlanta for lying to a federal grand jury.

The central issue of the trial was espionage. In August 1948, Whittaker Chambers—a senior editor at Time magazine—was called by the House Committee on Un-American Activities to corroborate the testimony of Elizabeth Bentley, a Soviet spy who had defected in 1945 and accused dozens of members of the U.S. government of espionage. One official she named as possibly connected to the Soviets was Alger Hiss.

The central issue of the trial was espionage. In August 1948, Whittaker Chambers—a senior editor at Time magazine—was called by the House Committee on Un-American Activities to corroborate the testimony of Elizabeth Bentley, a Soviet spy who had defected in 1945 and accused dozens of members of the U.S. government of espionage. One official she named as possibly connected to the Soviets was Alger Hiss.

The FBI immediately began probing her claims to ensure those who were credibly named—including Hiss—did not continue to have access to government secrets or power. As the investigation into Bentley and related matters deepened in 1946 and 1947, Congress became aware of and concerned about the case. Details leaked to the press, and the investigation became national news and embroiled in partisan politics in the run up to the 1948 presidential election.

Chambers, who had renounced the Communist Party in the late 1930s, testified reluctantly that hot summer day. He ultimately acknowledged he was part of the communist underground in the 1930s and that Hiss and others had been members of the group.

In later testimony, Hiss vehemently denied the accusation. After all, Chambers had offered no proof that Hiss had committed espionage or been previously connected to Bentley or the communist group.

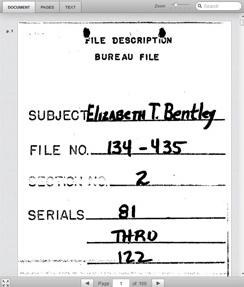

View Soviet spy Elizabeth Bentley’s FBI file.

It could have ended there, but members of the committee—especially then-California Congressman Richard Nixon—prodded Chambers into disclosing information suggesting there was more to his story and his relationship with Hiss. In later testimony, Hiss admitted knowing Chambers in the 1930s, but he continued to deny any ties to communism and later filed a libel suit against his accuser.

The committee was torn. Who was telling the truth, Hiss or Chambers? And should either be charged with perjury?

A key turn of events came in November 1948, when Chambers produced documents showing both he and Hiss were committing espionage. Then, in early December, Chambers provided the committee with a package of microfilm and other information he had hidden inside a pumpkin on his Maryland farm. The two revelations, which became known as the “Pumpkin Papers,” contained images of State Department materials—including notes in Hiss’ own handwriting.

It was the smoking gun the Justice Department needed. Hiss was charged with perjury; he could not be indicted for espionage because the statute of limitations had run out. An extensive FBI investigation helped develop a great deal of evidence verifying Chambers’ statements and revealing Hiss’ cover-ups.

In 1949, the first trial resulted in a hung jury, but in 1950, Hiss was convicted. Sixty-three years ago today, he was sentenced to five years in prison, ending an important case that helped further confirm the increasing penetration of the U.S. government by the Soviets during the Cold War.