FBI San Francisco History

Early 1900s

The FBI opened an office in San Francisco during its earliest days as an organization, and one has been in continuous operation ever since. The first known special agent in charge was E.M. Blanford in 1911.

During these early years, the San Francisco Division handled many important matters for the Bureau, including some of its most significant national security cases. In 1916, for instance, San Francisco agents investigated German Consul General Franz Bopp and his assistants—as well as a number of Indian-born residents—for violating the Neutrality Act and the Sherman Anti-Trust Act. In what became known as the Hindu Conspiracy case, German nationals sought to help Indian nationals plan, fund, and carry out an uprising against British colonial rule in India. Bopp and his fellow Germans were convicted in January 1917 and were later interned as alien enemies when the U.S. declared war on Germany in April 1917.

In August 1920, San Francisco was named one of nine divisional headquarters in the Bureau, with administrative charge over a number of other field offices in the western United States.

Thanks to expanded federal legislation, the transportation of stolen cars across state lines became an important responsibility of the division and the rest of the Bureau in the 1920s, as did kidnapping in 1932. The division later played a key role in solving an extortion case following the kidnapping of three-year-old Marc de Tristan Jr., the son of Count and Countess de Tristan. One month after the boy had been safely recovered, an attempt was made to extort money from the family, threatening harm to the child. Special agents investigated and obtained a confession from a man named Raymond Parker.

Early San Francisco Field Office building

1940s

The onset of World War II led to a significant increase in the responsibilities of the San Francisco Division. The great majority of its cases during this time involved counterespionage and domestic security issues; agents, for example, monitored the activities of Japanese language students possibly engaged in espionage and of German Consular Officer Fritz Wiedemann, who was suspected of being an intelligence officer.

The division also worked closely with local industry to protect factories from sabotage, helping set up appropriate security measures and protocols. It also coordinated with other federal agencies to monitor and uncover spies operating in this country and to gather intelligence on foreign espionage activities.

Even before the war was over, San Francisco agents began noticing an increase in Soviet espionage. At the end of the war, the division began to reprioritize its counterintelligence work by tracking Soviet consular officials and the Communist Political Association (later the U.S. Communist Party) and its connection to Soviet intelligence in the Bureau’s Comintern Apparatus case.

Despite the strong focus on national security, interstate transportation of stolen motor vehicles, violations of the Selective Service Act, anti-trust matters, and many other violations were of significant concern to San Francisco in the post-war period.

By 1949, the San Francisco Division covered the entire Northern Judicial District of California, an area of 73,274 square miles with an estimated population of nearly four million people. Its territory included 41 of the 58 counties of the state of California, plus Yosemite National Park. In addition to its office in the city of San Francisco, the division operated a total of 21 satellite offices, or resident agencies, including in Alameda, Berkeley, Carmel, Chico, Eureka, Hayward, Kentfield, Marysville, Modesto, Oakland, Palo Alto, Redding, Richmond, Sacramento, Salinas, San Jose, Santa Cruz, Santa Rosa, Stockton, Vallejo, and Walnut Creek.

1950s

With the onset of the Cold War, the 1950s were a busy time for the San Francisco Division. A number of high-priority espionage and domestic security cases led to the apprehension of several foreign agents. The division, for example, investigated communist labor leader Harry Bridges and nuclear physicist J. Robert Oppenheimer in what became major cases. In the latter investigation, the FBI discovered evidence that called into question the veracity of Oppenheimer’s statements about his ties to communism and led to his security clearance being revoked by the Atomic Energy Board. The Bureau did not find evidence that Oppenheimer had betrayed American nuclear secrets to the Soviets, and evidence suggests that he cut his ties to communist influences when approached by people who encouraged him to spy.

At the same time, the division continued its work to investigate and deter crime. In one case, a San Jose man went on a crime spree—stealing cars, robbing banks, and ultimately killing two people. San Francisco Special Agent C. Darwin Marron persuaded the man’s mother to help catch him. When Marron returned to town, his mother told the FBI, and the man was arrested two days later. The killer ultimately confessed to the crimes.

Another case—investigated in conjunction with the FBI’s Los Angeles Division—focused on numerous thefts from McClellan Air Force Base in Sacramento (a separate case was opened in that city in 1967). Seven subjects were indicted on charges of bribery, theft of government property, and conspiracy. By April 1959, all seven had either pled guilty or were convicted at trial.

Alcatraz Island in San Francisco Bay in 1932

1960s

By the end of 1960, the San Francisco Division had 270 special agents and 155 clerks on board and was handling nearly 4,700 cases. The division still worked on espionage and domestic security cases, but major crime investigations were growing in importance.

In 1962, the division became involved in one of the most famous prison break investigations in U.S. history when three inmates at Alcatraz pulled off an elaborate escape. As part of their plan, the three men fashioned dummy heads, a homemade drill, makeshift life preservers, and a rubber raft built out of more than 50 stolen raincoats. Investigators reconstructed their meticulous plot, but to this day we don’t know where the men are or whether they survived their passage across the cold waters of the Pacific that surrounded Alcatraz.

Other fugitives weren’t so successful. In 1961, San Francisco agents captured an impostor attorney who called himself Daniel Jackson Oliver Wendell Homes Morgan. Another fugitive, Arthur Vernon Watson, was apprehended without incident in a heavily crowded bus terminal. The dangerous fugitive was a habitual criminal, convicted earlier of second degree murder. In November 1963, working with agents from Atlanta, the division tracked down Top Ten Fugitive John B. Everhart—who was wanted for murder—while he was painting a house in San Francisco. The following year, it captured two more Top Ten fugitives—murder suspect John Robert Bailey and bank robber George Zavada.

The division also assisted in the investigation into the May 7, 1964 crash of Pacific Air Flight 773 that killed 44 people. Investigators recovered the gun at the crash site near San Ramon and were able to identify the suspect, Francisco Gonzalez, who had stormed the cockpit and shot the pilot and first officer. The Bureau also helped to identify the victims.

By the end of 1960s, the San Francisco Division employed 270 agents and 155 clerks and was handling nearly 4,700 cases.

1970s

During the turbulent 1970s, domestic terrorism became a key focus of the San Francisco Division, which was instrumental in investigating such groups as the Symbionese Liberation Army and the New Dawn.

One of the most famous cases in U.S. history—the kidnapping of newspaper heiress Patty Hearst—took place in San Francisco in February 1974. Two months later, Hearst emerged during a local bank robbery, apparently working as a member of the Symbionese Liberation Army, the domestic terrorist group that had kidnapped her. After a massive search led by the San Francisco Division, Hearst was located and arrested by San Francisco agents in September 1975 and convicted of bank robbery. She was later pardoned by President Carter.

Meanwhile, San Francisco personnel kept working to protect the country from foreign espionage. The division handled several major spy cases during the 1970s. In 1977, for example, Christopher John Boyce was arrested in California and Andrew D. Lee in Mexico on charges arising from their involvement in Soviet espionage. A few months later, Park Tong Sun (also known as Tongsun Park) was indicted on 36 felony counts in an influence-buying conspiracy that involved several South Korean intelligence officers.

In November 1978, the San Francisco Division helped investigate the tragic mass suicide at Jonestown in Guyana, South America, including the murder of California Congressman Leo Ryan. Jim Jones, the leader of the cult-like settlement, was found dead as well after ordering his followers to drink a cyanide-laced drink. San Francisco investigators helped unravel the chain of events and make the case against Jones’ associate Larry Layton, who was ultimately convicted and sentenced to life in prison.

Patty Hearst

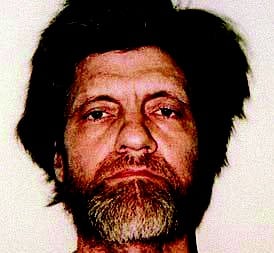

Ted Kaczynski

1980s and 1990s

During the 1980s, government-wide efforts against espionage and foreign intrigue quickened in the Bureau and the San Francisco Division. In 1983, San Francisco agents arrested James Durward Harper, Jr., who was charged with providing classified documents to Polish intelligence beginning in 1975. The next year, investigators arrested Jerry Whitworth for feeding naval cryptographic secrets to John Walker, who sold them to the Soviet Union for many years. And in 1986, an Air Force clerk/airman named Bruce D. Ott was arrested and charged with attempting to pass national defense information to undercover San Francisco agents posing as Soviets. Ott was found guilty and sentenced to 25 years in prison.

One of the most important cases that the division contributed to during the 1980s and 1990s was the search for the elusive “Unabomber”—ultimately identified as Ted Kaczynski—who killed three and injured two dozen from 1978 until his capture in 1996. Three of Kaczynski’s bombs targeted victims in San Francisco—two professors and one graduate student of the University of California, Berkeley—and FBI investigators correctly assumed that Kaczynski had ties to the Bay area (he had been a professor at Berkeley). For many years, the San Francisco Division led the multi-agency “UNABOM” Task Force investigation. Kaczynski was arrested by the FBI in his secluded Montana cabin in April 1996 after his brother recognized writings that the bomber had asked to be published in The New York Times and The Washington Post in September 1995. Kaczynski was ultimately sentenced to life in prison.

The division also investigated the 1984 murder of Taiwanese journalist Henry Liu in a suburb of San Francisco. The case resulted in the conviction in Taiwan of several members of the United Bamboo gang—a violent Asian criminal enterprise—as well as one conviction in California. The United States later held the government of Taiwan responsible for the slaying. The FBI’s case also led to several spin-off investigations of high-ranking crime bosses and corrupt officials in Taiwan.

After the Soviet Union collapsed in 1991, the FBI in San Francisco and nationwide began to focus more of its attention on domestic crime issues. For its part, the division started dismantling many underground crime networks and clamping down on white-collar crime. In 1994, for example, the division began investigating an upstart San Francisco company called Golden Ada that specialized in cutting and polishing rough diamonds from Russia. The expanding multi-agency case—which grew to include Russian law enforcement—revealed that the company had orchestrated a scheme to defraud the Russian government out of some $170 million in diamonds and other valuables through illegal agreements with other companies. Several individuals pled guilty or were convicted in the case, including in Moscow.

One of the most successful cases was “Operation Bytes Dust,” a multi-agency investigation into an international heroin trafficking ring that began in December 1994. Thanks to a confidential informant, we learned that the ring was importing the narcotic into San Francisco, Boston, and Toronto from Thailand and Vietnam. The expanding investigation revealed that the enterprise was responsible for an unprecedented crime wave across the country during the mid-90s. In addition to drug trafficking, the organization was involved in murder, kidnapping, alien smuggling, home invasion and business robberies, extortion, credit card fraud, firearms trafficking, and the exporting of stolen luxury vehicles to Asia. The most lucrative of these activities were takeover-type armed robberies of computer companies, during which employees were bound, gagged, and held at gunpoint while computer chips and related products were stolen. In April 1996, 24 principal suspects were arrested in eight states and charged with racketeering , robbery, drug trafficking, and other offenses. Additional indictments followed, resulting in some 200 more arrests. In June 2000, the four leaders of this criminal enterprise were convicted.

Post-9/11

After the attacks of 9/11, the San Francisco Division responded by lending its personnel and resources to the unfolding investigation. One of the hijacked planes—United Flight 93—was actually scheduled to fly to San Francisco before it crashed into a field in rural Pennsylvania. The division sent a number of its Evidence Response Team experts to New York to work at the scene of the World Trade Center. Members of its Hazardous Materials Response Team traveled to the East Coast to support the anthrax investigation in October 2001. Soon after the attacks, the San Francisco Division also warned the California governor of credible terrorist threats against the Golden Gate Bridge.

At the same time, the division made significant operational changes like the rest of the FBI as a result of its new overriding mandate to prevent terrorist attacks. It quickly doubled the number of agents working terrorism matters, strengthened its San Francisco Joint Terrorism Task Force (JTTF), and added terrorism squads in Oakland and San Jose. To boost its intelligence capabilities, the division integrated the California Anti-Terrorism Information Center into the San Francisco JTTF to provide law enforcement agencies in the state with timely and valuable intelligence relating to terrorism. In 2003, the San Francisco Division also created a Field Intelligence Group to bolster its ability to share information and take proactive steps against both national security and criminal threats.

The division’s growing capabilities were put to use in tracking the activities of international terrorists both here and abroad. In one case, the San Francisco JTTF and partner agencies gathered evidence that led to the 2007 indictment of two brothers for providing material support to global terrorists. One brother was arrested; the other remains a fugitive, most likely in the Philippines.

In 2002, the law finally caught up with the last Symbionese Liberation Army fugitive, James Kilgore, when he was arrested in South Africa and extradited to San Francisco. He was convicted of second-degree murder in 2003 and federal passport and explosives charges in 2004.

In 2003, San Francisco agents began investigating an animal rights extremist named Daniel Andreas San Diego, who allegedly bombed two area office buildings and went into hiding. In April 2009, San Diego was added to the FBI’s Most Wanted Terrorists list—the first domestic terrorist to be added to that list.

The division has continued to address criminal threats as well, targeting such violent street gangs as Mara Salvatrucha, or MS-13; identifying corrupt public figures like Ed Jew of the San Francisco Board of Supervisors, who pled guilty in 2008 to extorting local small businesses; helping to investigate a massive price-fixing scheme involving LCD panels; and participating in the probe of steroids in Major League Baseball. San Francisco investigators have also led a number of white-collar crime cases, including major corporate fraud investigations.

The San Francisco Division remains committed to protecting the people and defending the nation while upholding the rule of law and the civil liberties of all.