Alcatraz Escape

Aerial view of Alcatraz Island in January 1932. The island was used as a maximum security federal prison from 1934 to 1963.

View of the interior of the Alcatraz Island prison in 1986, looking south from the third level guard station with cell block B on the left and cell block C on the right. Library of Congress photograph.

In its heyday, it was the ultimate maximum security prison.

Located on a lonely island in the middle of San Francisco Bay, Alcatraz—aka “The Rock”—had held captives since the Civil War. But it was in 1934, the highpoint of a major war on crime, that Alcatraz was re-fortified into the world’s most secure prison.

Its eventual inmates included dangerous public enemies like Al Capone and George “Machine Gun” Kelly, criminals who had a history of escapes, and the occasional odd character like the infamous “Birdman of Alcatraz.”

In the 1930s, Alcatraz was already a forbidding place, surrounded by the cold, rough waters of the Pacific. The redesign included tougher iron bars, a series of strategically positioned guard towers, and strict rules, including a dozen checks a day of the prisoners. Escape seemed near impossible.

Despite the odds, from 1934 until the prison was closed in 1963, 36 men tried 14 separate escapes. Nearly all were caught or didn’t survive the attempt.

The fate of three particular inmates, however, remains a mystery to this day. Here is their story.

The Escapees

Frank Morris arrived at Alcatraz in January 1960 after convictions for bank robbery, burglary, and other crimes and repeated attempts to escape various prisons. Later that year, a convict by the name of John Anglin was sent to Alcatraz, followed by his brother Clarence in early 1961. All three knew each other from previous stints in prison.

Assigned to adjoining cells, they began hatching a plan to escape. Morris, known for his intelligence, took the lead in the planning. They were aided by another inmate, Allen West.

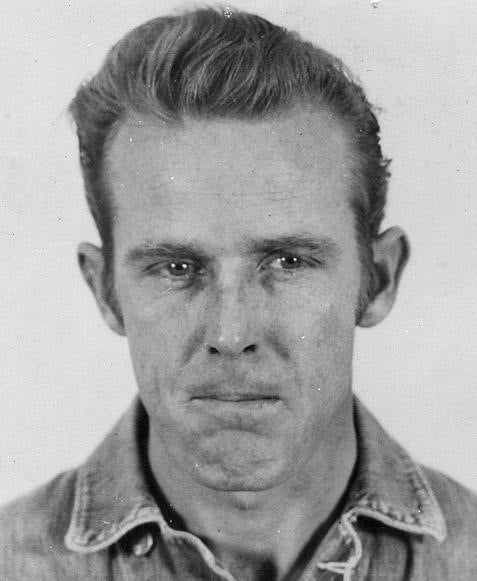

John Anglin

Clarence Anglin

Frank Morris

Missing

On June 12, 1962, the routine early morning bed check turned out to be anything but. Three convicts were not in their cells: John Anglin, his brother Clarence, and Frank Morris.

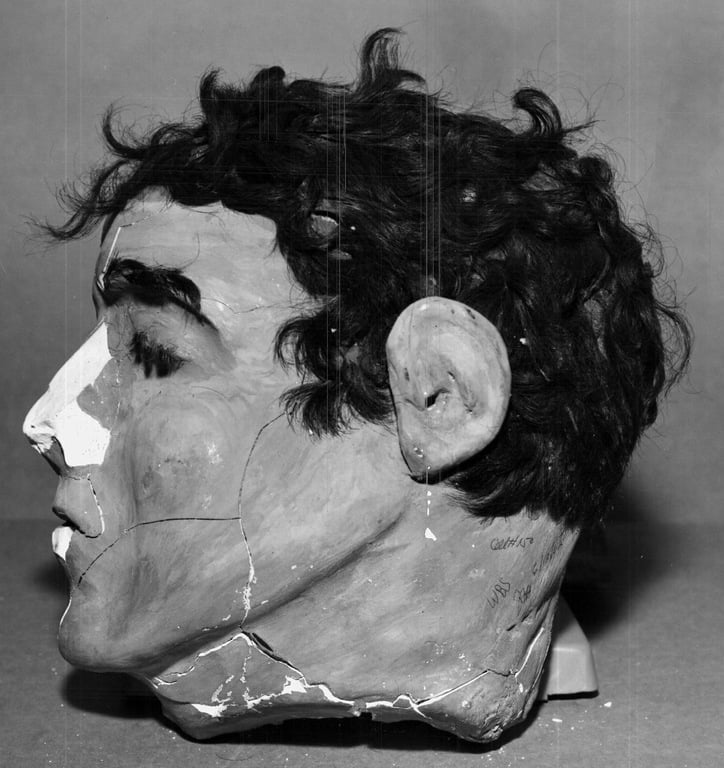

In their beds were cleverly built dummy heads made of plaster, flesh-tone paint, and real human hair that apparently fooled the night guards. The prison went into lock down, and an intensive search began.

Profile of the dummy head found in Morris’ cell. The broken nose resulted when the head rolled off the bed and struck the floor after a guard reached through the bars and pushed it.

This photo, taken in Clarence Anglin’s cell, shows how the dummy heads were arranged to fool the guards into thinking the inmates were asleep.

Gathering the Clues

We were notified immediately and asked to help.

Our office in San Francisco set leads for offices nationwide to check for any records on the missing prisoners and on their previous escape attempts (all three had made them). We also interviewed relatives of the men and compiled all their identification records and asked boat operators in the Bay to be on the lookout for debris.

Within two days, a packet of letters sealed in rubber and related to the men was recovered. Later, some paddle-like pieces of wood and bits of rubber inner tube were found in the water. A homemade life-vest was also discovered washed up on Cronkhite Beach, but extensive searches did not turn up any other items in the area.

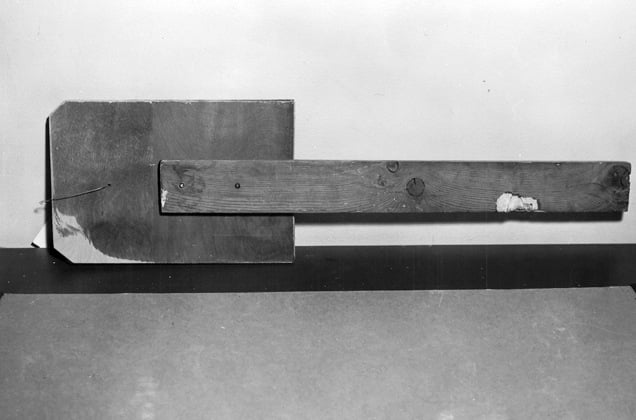

Homemade paddle recovered at prison. A similar one was recovered on Angel Island.

One of the life vests made by the inmates

Piecing Together the Plan

As the days went by, the FBI, the Coast Guard, Bureau of Prison authorities, and others began to find more evidence and piece together the ingenious escape plan. We were aided by inmate Allen West, who didn’t make it out of his cell in time and began providing us with information. Here’s what we learned.

- The group had begun laying plans the previous December when one of them came across some old saw blades.

- Using crude tools—including a homemade drill made from the motor of a broken vacuum cleaner—the plotters each loosened the air vents at the back of their cells by painstakingly drilling closely spaced holes around the cover so the entire section of the wall could be removed. Once through, they hid the holes with whatever they could—a suitcase, a piece of cardboard, etc.

- Behind the cells was a common, unguarded utility corridor. They made their way down this corridor and climbed to the roof of their cell block inside the building, where they set up a secret workshop. There, taking turns keeping watch for the guards in the evening before the last count (see the crude “periscope” they constructed for the lookouts), they used a variety of stolen and donated materials to build and hide what they needed to escape. More than 50 raincoats that they stole or gathered were turned into makeshift life preservers and a 6x14 foot rubber raft, the seams carefully stitched together and “vulcanized” by the hot steam pipes in the prison (the idea came from magazines that were found in the prisoners’ cells). They also built wooden paddles and converted a musical instrument into a tool to inflate the raft.

- At the same time, they were looking for a way out of the building. The ceiling was a good 30 feet high, but using a network of pipes they climbed up and eventually pried open the ventilator at the top of the shaft. They kept it in place temporarily by fashioning a fake bolt out of soap.

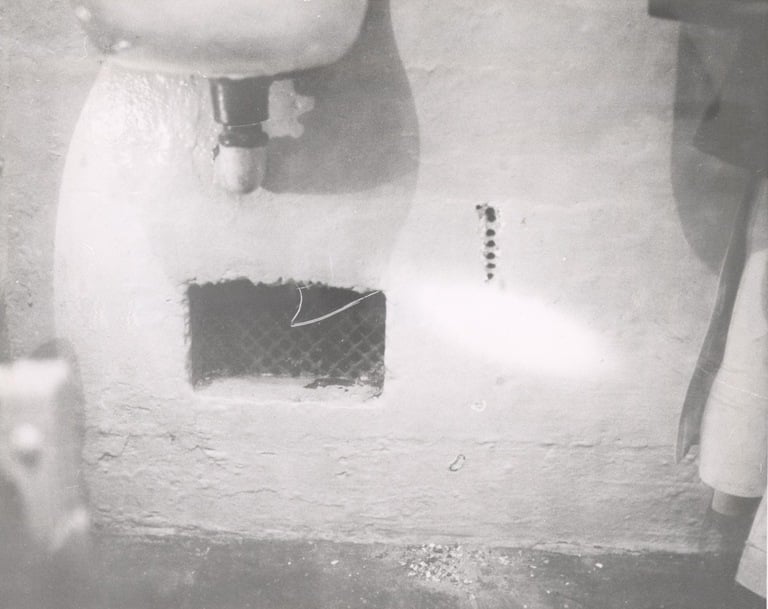

Ventilation grate through which prisoners gained access to the utility corridor behind Cell Block “B.”

Portion of concealed area on top of Cell Block “B” Prisoners constructed tools for their escape here.

The Escape

On the evening of June 11, they were ready to go.

West, though, did not have his ventilator grill completely removed and was left behind.

The three others got into the corridor, gathered their gear, climbed up and out through the ventilator, and got on to the prison roof. Then, they shimmied down the bakery smoke stack at the rear of the cell house, climbed over the fence, and snuck to the northeast shore of the island and launched their raft.

View from catwalk above Cell Block B showing route prisoners took to access the roof of Cell House

Ventilator cover on the roof of the Alcatraz prison through which the inmates made their escape

Plenty of people have gone to great lengths to prove that the men could have survived, but the question remains: did they? Our investigation at the time concluded otherwise, for the following reasons:

- Crossing the Bay. Yes, youngsters have made the more than mile-long swim from Alcatraz to Angel Island. But with the strong currents and frigid Bay water, the odds were clearly against these men.

- Three if by land. The plan, according to our prison informant, was to steal clothes and a car once on land. But we never uncovered any thefts like this despite the high-profile nature of the case.

- Family ties. If the escapees had help, we couldn’t substantiate it. The families appeared unlikely to even have the financial means to provide any real support.

- Missing in action. For the 17 years we worked on the case, no credible evidence emerged to suggest the men were still alive, either in the U.S. or overseas.

For more information:

- Vault records on the Alcatraz Escape

- More pictures in our Multimedia website