FBI Memphis History

Early 1900s

The Bureau’s first field office in Memphis was opened prior to 1925, although the exact date is unknown. From February 1925 to December of that year, the special agent in charge was T.M. Daniel.

In 1930, the office closed, and its territory was split between the Dallas and Oklahoma City Divisions. The Bureau’s responsibilities began to ramp up as hostilities increased in Europe. As a result, the Memphis Division reopened in 1937, with Special Agent in Charge T.N. Stapleton at its helm. It has been in continuous operation since then.

1940s and 1950s

During the 1940s, national security issues became a priority throughout the FBI. Memphis agents investigated internal security matters, Selective Service Act violations, and a few sabotage and espionage cases.

In 1941, part of Memphis’ territory and cases were transferred to the new Jackson, Mississippi Division; the total number of agents in Memphis was reduced from 47 to 24. However, over the course of World War II—and especially after passage of the Atomic Energy Act in 1946—the division’s personnel complement and case load rose steadily.

Also in 1941, Special Agent Julius Lopez was named Assistant Special Agent in Charge in Memphis. He is recognized as the first person of Hispanic heritage to rise to that position in the Bureau. Lopez served from 1941 to 1942, when he was promoted to acting Special Agent in Charge of San Juan Division. After holding other positions, he returned to Memphis as Special Agent in Charge in 1957.

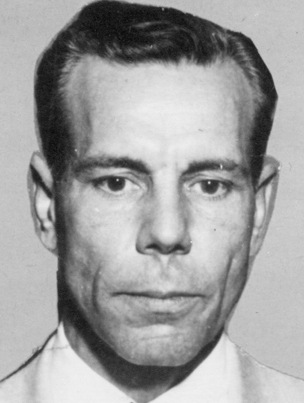

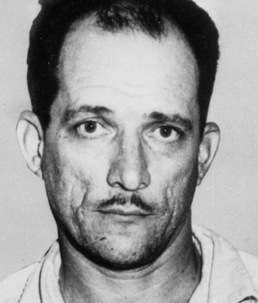

In March 1950, the FBI launched its Ten Most Wanted Fugitives program. Over the next seven years, Memphis agents captured four of the notorious fugitives on the list. The first came in 1953, when agents apprehended Arnold Hinson in Memphis. Hinson had killed a co-worker in Montana. Kenneth Carpenter—who violated his release terms from a bank robbery conviction—was the next fugitive captured. He was arrested in Arlington, Tennessee in 1955 after an alert agent recognized the unusual “Love” tattoo on his hand as he sat in a parked car. The next year, Memphis agents arrested Nick Montos, who had been jailed for armed robbery and sexual assault and was one of a few fugitives who made the Top Ten list twice. And in 1957, division agents nabbed Alfred James White in Memphis after being tipped off by a citizen who had seen his mug shot on a wanted poster. White was wanted for robbing a lumberyard and shooting a police officer while fleeing.

During the 1950s, bank robberies and stolen motor vehicle cases increased in Memphis, as did overall convictions and recoveries.

Early Memphis field office

Arnold Hinson

Kenneth Carpenter

Nick Montos

Alfred James White

1960s and 1970s

FBI Memphis stayed extremely busy with civil rights matters during the turbulent 1960s. Agents investigated assaults on African-Americans (including some by law enforcement); racial and housing discrimination; election law irregularities (denials to vote or register to vote); and riots or other results of desegregation. These cases were complicated and sensitive and required more manpower than many previous crimes. In 1963, for example, civil rights and racial matters accounted for only four percent of the division’s cases, but the investigations required almost 25 percent of its manpower and 30 percent of its overtime.

Special Agent in Charge Karl Dissly, who served in the early 1960s

A key leader during this period was Clarence M. Kelley. He served as the Memphis Special Agent in Charge from 1960 to 1961, when he retired to become the police chief in Kansas City, Missouri. Kelley returned to the FBI in 1973 to serve as Director, a position he held until 1978.

In the late 1960s, the division worked a number of cases involving cotton production, a vital industry in the Memphis area. Since cotton’s quality and value deteriorate over time, the grading of cotton stock was crucial, and fraudulently graded cotton could cost the federal government up to $15 per bale. In 1967, the Memphis Division learned that a Kempner Cotton Company purchaser was paying bribes so that 14,000 bales would be improperly downgraded. Agents conducted exhaustive interviews and physical surveillance, leading to the arrest of a dozen U.S. Department of Agriculture employees and cotton buyers on bribery and fraud charges. The division’s thorough investigation saved the U.S. government $200,000 and heightened awareness of need for stringent monitoring of potential fraud.

The next year, the division investigated its most famous case—the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. In April 1968, Dr. King had stopped in Memphis to support a sanitary workers’ strike for improved treatment. While standing on the balcony of the Lorraine Motel, King was shot by James Earl Ray, a known racist with a lengthy criminal record. Memphis agents responded immediately, tracking down clues that pinpointed Ray as the culprit. Agents determined that Ray, using an alias, had purchased a rifle and rented a hotel room near the crime scene. Agents also found his fingerprints on a rifle and in a car. With assistance from Scotland Yard, the FBI tracked down Ray in London two months later. He initially confessed to the assassination—possibly to avoid the death penalty—then recanted and claimed he was set up by a mysterious individual named “Raoul.” The Department of Justice reviewed this conspiracy theory but found no evidence “Raoul” existed or that others were involved.

In the 1970s, Memphis also worked a case that would be significant for its innovations in voice identification and corroboration—and the first use of these techniques in federal court. The investigation centered on professional bank extortionists Larry Nein and Leonard Petersimes, who had extorted over $500,000 in 20 schemes across the nation. Their luck ran out in Memphis in 1976, when they threatened to bring harm to a banker’s family and bomb his bank. Quick-acting agents caught the pair retrieving a $100,000 payoff from the banker. Voice identifications nailed the extortionists by identifying them as the source of the threats. FBI Headquarters noted that the techniques Memphis applied would promptly solve 30 similar pending cases and countless more in the future.

The Memphis Division handled other financial industry related crimes as well. The city of Memphis was world’s third largest municipal bond center, so the office remained busy chasing check kiters and other white-collar criminals. In one late 1970s investigation, agents uncovered evidence that L.O.C. Industries was running a multi-million dollar scheme to fraudulently sell more than 1,000 distributorships and bilk victims (mainly small businesses) out of $50,000-$70,000 per day.

Bank robberies were also a serious concern for the division at this time. During the mid-1970s, twenty-year-old Billy Ray Dawson led a gang in 30 heists across the southeastern United States; each robbery yielded between $50,000-100,000. The gang wore ski masks and jumpsuits, carried semiautomatic rifles and Bushmaster pistols, and assaulted bank employees as they committed their robberies. FBI Memphis and other southeastern offices spent many hours trying to catch the gang. They finally did following the robbery of the McEwan bank in Memphis. Although the gang got away with more than $59,000, law enforcement was close on their tail following the robbery. The criminals hid in nearby woods, but local authorities and Memphis agents brought in tracking dogs and quickly pinpointed their location. A gunfight ensued, but the firepower of the agents and police forced the gang to surrender.

Another significant area of crime for the Memphis Division was public corruption. In the late 1970s, the office began receiving a number of calls from state and local government officials about corruption issues. These tips led to a number of Memphis area sheriffs and deputies being convicted of taking payoffs for not enforcing state and local liquor laws. In another investigation code-named SHELBCO (short for the Shelby County Case), county and city employees were convicted for giving public works construction and paving contracts to select contractors in exchange for payoffs and “Christmas gifts.”

1980s and 1990s

In the coming decade, the number of corruption cases grew more widespread and began to reach higher levels of government—even touching Tennessee Governor Leonard Ray Blanton and members of his administration. In 1980, Blanton and two of his aides were indicted for their roles in a scheme to provide liquor licenses to those who agreed to pay a portion of their profits from the licenses. Another serious investigation involving Blanton and his cronies was TENNPAR (short for Tennessee Pardon), which investigated the large-scale illegal release of serious offenders from the state penitentiary by the state parole board in exchange for bribes. Blanton was convicted and sent to prison.

During the 1980s, Memphis ran Operation Rocky Top with the Tennessee Bureau of Investigation and the IRS. This joint effort found illegalities and bribery among charity bingo operators, lobbyists, regulators, and state legislators. State Congressman Randy McNally and House Speaker—and later Governor—Ned McWherter helped the Bureau in the case and received praise for their support. By the end of the operation, more than 50 individuals—included state legislators—were convicted.

To deal with so many serious public corruption investigations, the Memphis Division had to close or reduce staffing levels at several resident agencies in order to assign enough agents to the cases. Other FBI divisions sent reinforcements as well. At this time, corruption cases accounted for about half of Memphis Division’s work hours; at least 100 subjects were under investigation and 11 new corruption cases needed to be initiated.

FBI Memphis also handled other types of investigations. In one operation, agents discovered that the National Coal Exchange was operating nationwide organized “boiler rooms,” selling coal contracts without the raw supplies to back them up. Hundreds of investors committed millions of dollars to phantom commodities. Following the division’s investigations, dozens of subjects pled guilty, and local fines reached $150,000. The IRS and the U.S. Attorney’s Office estimated that the case saved the government $5 million in lost revenue from an illegal tax shelter and $25 million in potential economic losses. Intelligence developed during the investigation resulted in numerous other investigations.

In one mid-1980s case worked with the Memphis Police Department, the division investigated two partners who operated a fictitious chop shop targeting commercialized auto stripping. Investigators uncovered 21 chop shops in Tennessee and Arkansas and arrested 146 individuals, 120 of whom were convicted. The case also led to the recovery of 265 vehicles valued over $3.6 million; stolen parts worth more than $100,000; 1,300 pounds of stolen dynamite; 166 pounds of marijuana; and automatic and other weapons.

In 1996, Memphis agents caught another Ten Most Wanted fugitive—Rickey Allen Bright. Wanted for the kidnapping, rape, and sexual assault of a minor, Bright was featured on an episode of America’s Most Wanted. The show received many calls, and one indicated that the fugitive was playing drums in a Nashville band. Agents and other investigators in the division’s Violent Crimes Task Force followed up the tip and found Bright playing at a local hotel with his band. He had changed his appearance and was using an alias, but when agents asked for identification, he admitted, “I’m the one you’re looking for.”

Post-9/11

Following the events of 9/11, preventing terrorist attacks became the overriding priority of the FBI—including the Memphis Division. In 2002, the division created a Joint Terrorism Task Force to combine the skills and resources of partner government agencies. It also began to reengineer its intelligence operations, creating a Field Intelligence Group to more effectively gather, share, and analyze intelligence on international and domestic threats.

In one domestic terror case, agents investigated the violent threat posed by a local white supremacist named Demetrius Van Crocker. A Tennessee farmer and former member of the right-wing National Socialist Movement, Van Crocker made no secret that he hated the government. In 2004, he devised a plan to build a “dirty bomb” to blow up a state or federal courthouse. A concerned citizen took him seriously enough to contact state authorities, who called the FBI. Van Crocker paid an undercover agent for what he thought was a nerve toxin and the explosives to disperse it. When Van Crocker showed up to finalize the deal, he was arrested. A search of his home turned up pipe bomb components, loaded weapons, and right-wing paraphernalia. He was convicted in 2006 sentenced to more than 28 years in prison.

FBI Memphis continues to investigate all nature of crimes under the FBI’s jurisdiction, such as bank robbery, gang violence, cargo theft, illegal drugs, and civil rights. Public corruption continued to be a key issue as well. In 2002, Memphis agents launched the Tennessee Waltz investigation based on a tip from an employee of the Shelby County Juvenile Court. The individual alleged that a local lobbyist acted as a “bagman” who paid lawmakers for favorable votes on legislation benefiting his clients. Memphis agents created a fictitious surplus recycling company and spread the word they wanted exclusive contracts and laws passed that would favor the company. Bribes of over $150,000 were paid out to corrupt politicians who took the bait. A dozen state legislators, county commissioners, and school board members were convicted or pled guilty. Tennessee Waltz’s outcome led to the passage of new state ethics laws and the creation of an independent ethics commission.

In keeping with the FBI’s mission, the Memphis Division has helped protect local communities and the nation for decades, and it is committed to carrying out this tradition in the coming years.

Surveillance photo from Tennessee Waltz investigation