The Flying Bank Robber

How a Resourceful Thief Was Captured 60 Years Ago

On April 15, 1959, six decades ago today, the FBI officially put the cuffs on Ten Most Wanted Fugitive Frank Sprenz, aka the “Flying Bank Robber,” in Laredo, Texas.

But Sprenz’s flight from the law had actually ended across the border some days earlier, thanks in part to Mexican authorities and, of all things, a meandering cow.

Sprenz had been in trouble with the law at an early age. By his late 20s, he had landed in federal prison in Akron, Ohio. In April 1958, he fashioned a key out of a piece of metal from his bed and managed to unlock his cell door. Sprenz and four of his fellow convicts overwhelmed the guards and fled. All but Sprenz were quickly killed or captured.

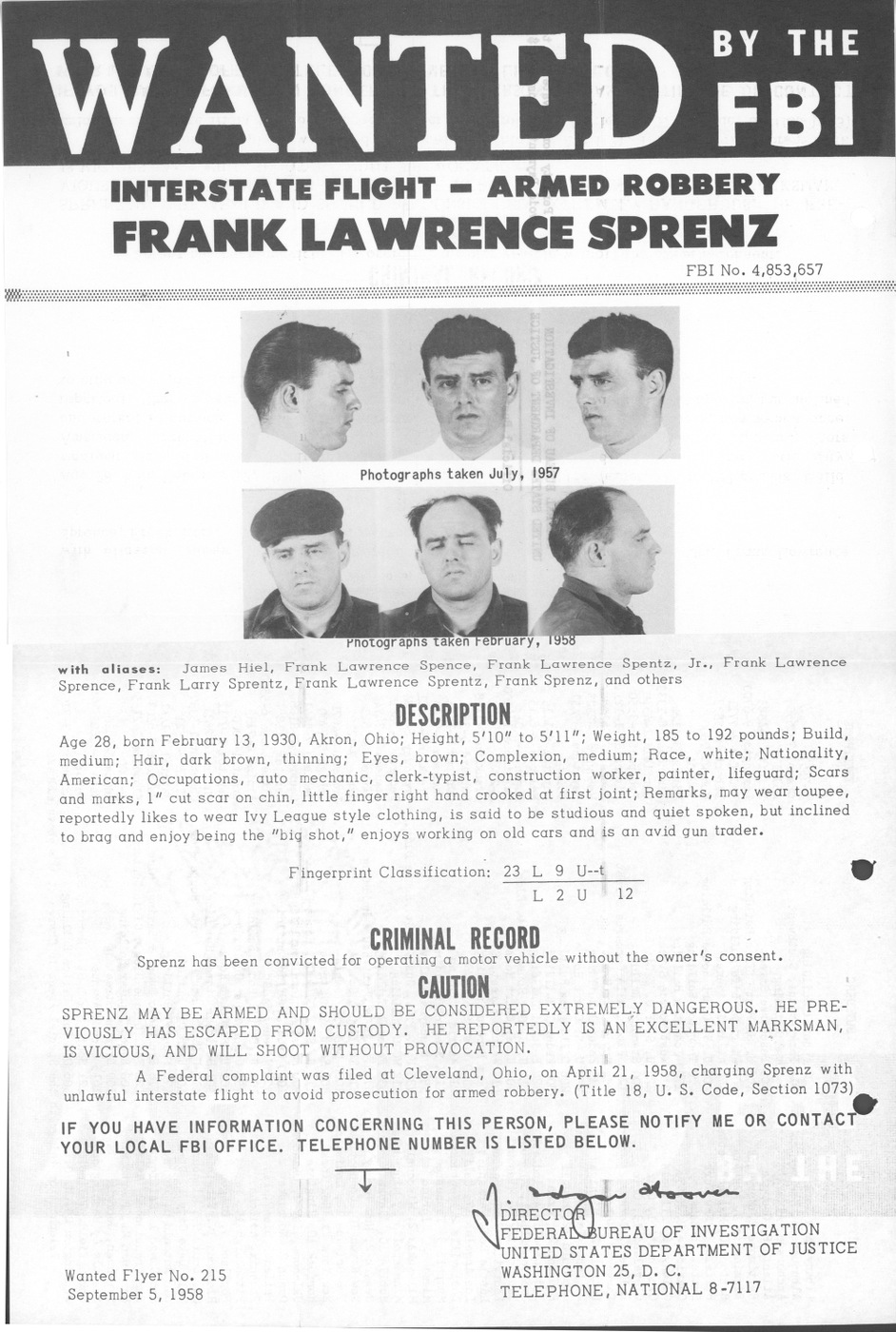

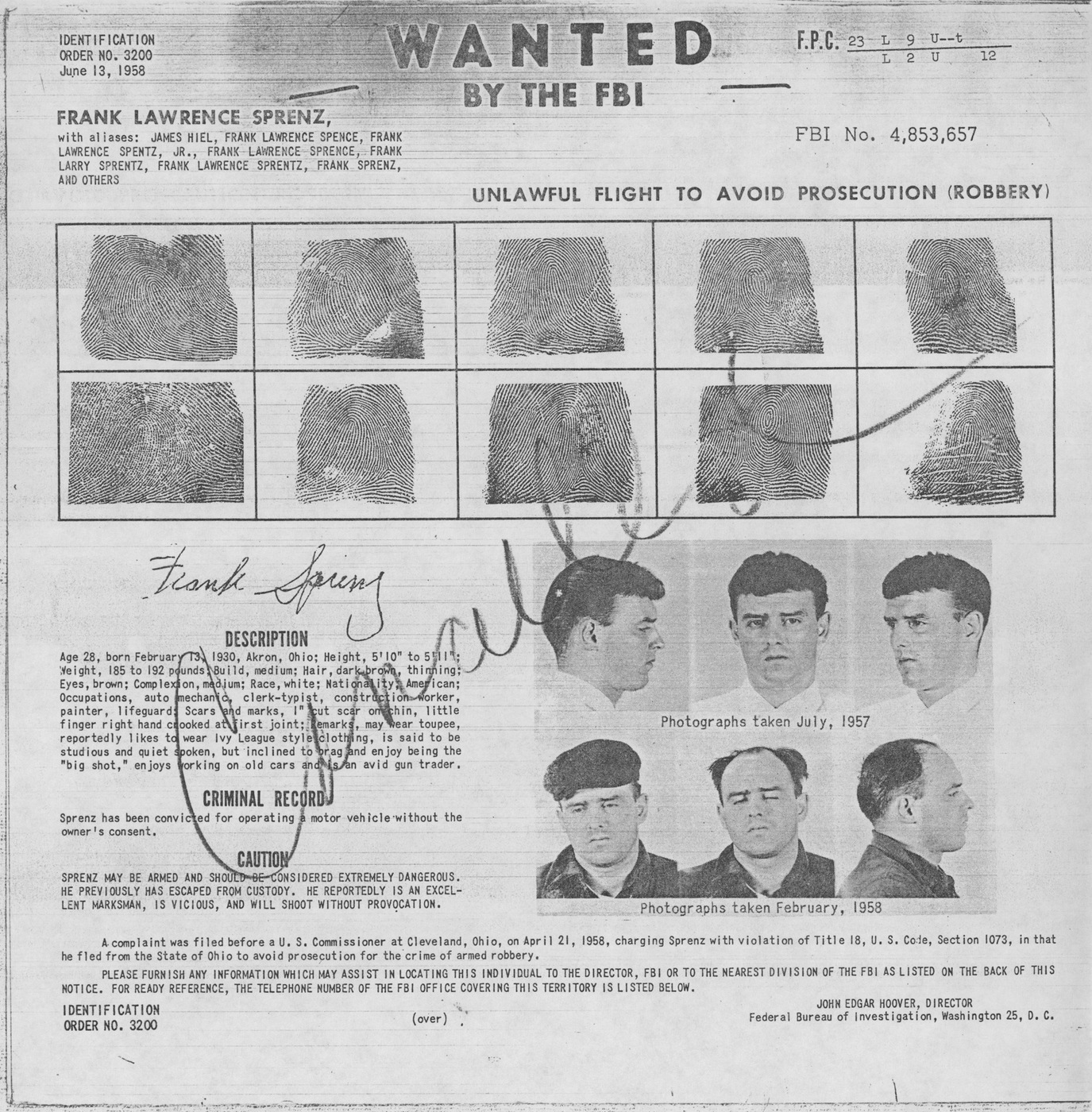

Following his jailbreak, Sprenz crossed state lines, giving the FBI jurisdiction in the case. Using a variety of aliases, stealing more than two dozen cars, and crisscrossing the country, Sprenz proved elusive. On September 10, 1958, the FBI added Sprenz to its Ten Most Wanted Fugitives list, and the hunt intensified.

Meanwhile, Sprenz continued his bank robbery spree. At one point, he traveled to Washington state, where he took flying lessons using the proceeds from one of his thefts. Now he was able to put into place a novel crime strategy that kept him a step ahead of law enforcement: He would steal a car, rob a bank, drive to the airport, snatch a plane, fly to a distant city, and repeat the process.

The plan worked, for a time at least.

In February 1959, Sprenz pilfered a plane in Scranton, Pennsylvania, and flew to Colchester, Vermont. The next month, he robbed a bank in Hamilton, Ohio, stealing around $25,000.

By this point, the FBI and its partners were in full pursuit. The Bureau’s office in Cleveland had the investigative lead, with offices around the nation providing crucial support. The FBI had already been working with international authorities, including in Canada, where Sprenz had reportedly stolen a plane.

When the news media further increased Sprenz’s notoriety by dubbing him the “Flying Bank Robber,” he decided to flee the country. Using a small plane he purchased with stolen money, he eventually flew to Raymondville, Texas, near the border of Mexico. Fearing he had been recognized, he quickly flew on to Mexico.

Sprenz was right—he had been spotted. Authorities contacted the FBI. The Bureau’s international office, or legal attaché, in Mexico City was put on alert.

Sprenz had refueled and was taking off for Cuba when fate intervened: A cow stepped in front of his plane, causing him to swerve and hit a tree. His plane was damaged beyond repair. An FBI legal attaché agent assisted Mexican authorities in tracking down Sprenz, and he was arrested and later returned to the U.S. He was found guilty of various crimes and sentenced to 25 years in jail. He was paroled in 1970 but later returned to his life of crime, and, ultimately, died in prison.

The capture of Frank Sprenz was a testament to two major pillars of the FBI’s work, then and now. First, it demonstrated the power of national and international cooperation, with both Mexican and Canadian authorities supporting the investigation. Second, the FBI’s Ten Most Wanted Fugitives program was crucial in his capture.

As Sprenz told the news media after his arrest, “Ever since I made the list, I've felt like I was walking down a glass sidewalk that might break at any minute. I'm glad it’s over.”

While partnerships with law enforcement and the public are instrumental to catching felons and fugitives like Sprenz, in this case, at least, an assist from a four-legged beast certainly didn’t hurt, either.