The Real Crime Scene Investigators

How the FBI trains its evidence response teams

Rush into a crime scene and you may destroy the tread marks the suspect left in the dirt. Handle a glass carelessly and you can mar the fingerprints left on it. Fail to notice a closet’s false back wall and you could leave behind suitcases of hidden cash. Seal a blood-soaked sock into a plastic bag and your evidence may mold before it reaches the crime lab.

The skill, knowledge, care, and precision of an evidence team can make or break a case. “If you mishandle a piece of evidence, it’s someone’s life. It is justice served or not served,” said Kari Shorr, an instructional systems design specialist for the FBI’s Evidence Response Team (ERT) Training Unit. “If these teams don’t do their jobs correctly, the impact on the back end is overwhelming.”

The FBI trains its evidence collection teams to be the best in the world. ERT Basic is where that training begins.

Evidence Response Team Basic Course

Inside what looks like an airplane hangar is a classroom with 26 students from FBI field offices across the country. Some are special agents. Others are intelligence analysts, forensic accountants, and computer experts. They are all here to learn how to process a crime scene—document it and gather and package the evidence—so the experts at the FBI Laboratories in Quantico, Virginia, and Huntsville, Alabama, can assess the evidence for forensic information. Everything they do has to be able to stand up to the scrutiny of a judge and a jury.

After taking an intensive online course, they will spend five days here. Some of the time will be in lectures, but most is spent on practical exercises that will test what they have learned and prepare them to take the skills back into the field to support the evidence response teams that deploy from every FBI field office.

Because every crime scene is unique—think about Unabomber’s 6x12 foot cabin and then the 845-mile-wide debris field after the bombing of Pan Am Flight 103—the teams learn an adaptable, iterative process and a set of fundamental skills. This includes when to call in specialists like forensic canines, dive teams, or bomb technicians.

Documenting a Scene

The course teaches students how to use photography combined with a sketch to document every aspect of a scene. Crime scene photographers capture a comprehensive view of the scene before the search process begins and after its completion. Each piece of evidence must also be photographed from three positions (long, medium, and close range) and then a fourth time with a ruler or scale that documents the item’s size.

The sketch provides the dimensions and distances that photographs can’t depict. The sketch will show, for example, exactly how far the gun was from the dead body.

If they are done properly, the photographs and the sketch together should give a prosecutor or investigators the ability to re-create the scene exactly or describe it in detail to a jury.

Interlaced within the meticulous documentation of a scene through photos, sketching, and evidence logs comes the part of the work that some team members describe as an odd type of treasure hunt. What will they find behind a door or buried in the field? What evidence will help tell the story of what happened?

Gathering Evidence

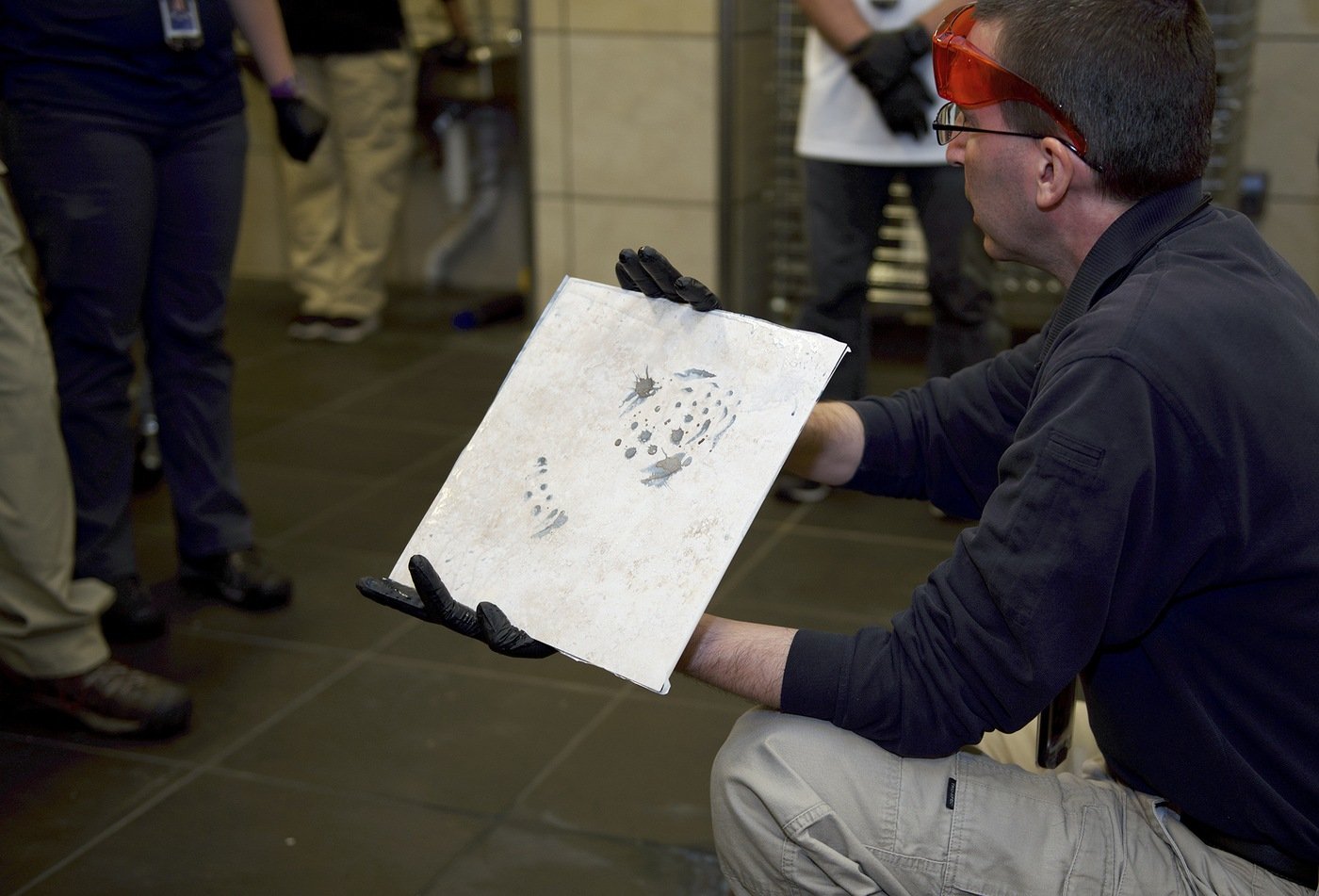

The French criminologist Edmond Locard, considered a pioneer in modern forensic science, asserted that every contact leaves a trace. Meaning any presence on a scene will leave evidence behind—fingerprints, blood, saliva, hairs and fibers, footprints, or tire treads. The job of a crime scene team is to find or uncover those points of contact.

Some evidence will clearly come to the fore—it will be visible to the naked eye or easily uncovered in a careful search. Other evidence will need to be coaxed into view. Evidence teams carry special light sources, chemicals, and tools to help illuminate, reveal, and gather what is invisible—faint dust trails from a person’s shoes, fingerprints on a soda can, or hidden stains.

This part of the job requires creativity, imagination, and extreme attention to detail. Does one wall look freshly painted when the others are worn? Could there be a reason the clutter is cleared off one area of the floor. Using the right tools, the evidence team may find the layer of fresh paint is covering up some writing and the oddly clear section of floor was wiped clean, but trace blood evidence remains.

The ERT Toolbox

Peer into the Evidence Response Team toolbox to see how everyday items and specialized equipment help the team process a scene.

“The FBI hires people for their intelligence, their integrity, their ability to think on their feet,” said Supervisory Special Agent Heather Thew. Thew serves as a new agent trainer for the FBI Academy and an instructor within the evidence response training unit. “Now we are training them for even a higher level of that assessment, but they are relying on those skills they already have.”

Once the team has uncovered pieces of evidence, they can collect it if it is moveable. If it’s not something they can move, they document it through photographs or take samples or swabs for the Lab to test. Packaging a piece of evidence properly is a final and crucial step to ensuring the Lab has the best material to work with. Even the best forensic examiner can’t do anything with a sample that was ruined on its way to Quantico or Huntsville.

“The FBI hires people for their intelligence, their integrity, their ability to think on their feet.”

Supervisory Special Agent Heather Thew

If the evidence is collected and packaged properly, the Lab has a deep forensic toolbox. It can analyze and then compare latent fingerprints to the millions of known prints from both criminal and civil files. Footprints and tire tracks can reveal the type and size of a shoe or tire and then reveal additional details based on wear. The Lab can determine what type of liquid soaked into the floorboards in an arson case or if that powdery substance is harmless or deadly.

As Kari Shorr reflects on the importance of the work they do at the training unit, she notes that while it’s hard to go from good to great, sustaining excellence is even harder. It takes an ongoing commitment to doing things right and understanding why care at a crime scene matters. “Know the importance of what you’re doing,” she said. “And know how important it is to the Bureau, to the victim, and to the nation.”

The Link Between ERT and the FBI Laboratory

Evidence teams close the gap between the crime scene and the FBI Laboratory. The job of the ERT is to find the evidence, document it, and preserve it.

The FBI’s full-service forensic laboratory can conduct:

- Fingerprint examination, comparison, and analysis

- DNA testing and analysis

- Firearms and toolmark forensics, including trajectory analysis for shooting incidents

- Examinations of physical evidence such as hair, fiber, soil, and skeletal remains

- Chemical analysis and toxicology

- Document examination and expertise

- Analysis of bomb components

Inside the FBI Podcast: Evidence Response Teams

On this episode of Inside the FBI, we’ll travel inside the world of Evidence Response Teams to learn why they exist, how they’re trained to approach crime scenes, and how their meticulous efforts on the ground help ensure that justice can be served in the courtroom.