Business E-Mail Compromise

An Emerging Global Threat

The accountant for a U.S. company recently received an e-mail from her chief executive, who was on vacation out of the country, requesting a transfer of funds on a time-sensitive acquisition that required completion by the end of the day. The CEO said a lawyer would contact the accountant to provide further details.

“It was not unusual for me to receive e-mails requesting a transfer of funds,” the accountant later wrote, and when she was contacted by the lawyer via e-mail, she noted the appropriate letter of authorization—including her CEO’s signature over the company’s seal—and followed the instructions to wire more than $737,000 to a bank in China.

The next day, when the CEO happened to call regarding another matter, the accountant mentioned that she had completed the wire transfer the day before. The CEO said he had never sent the e-mail and knew nothing about the alleged acquisition.

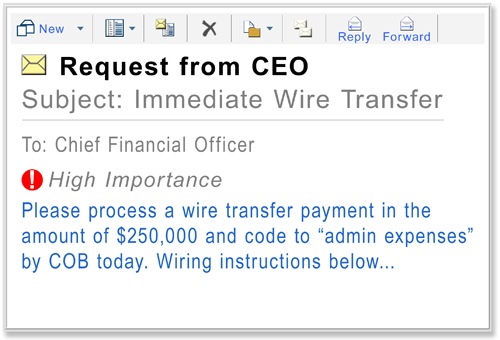

The company was the victim of a business e-mail compromise (BEC), a growing financial fraud that is more sophisticated than any similar scam the FBI has seen before and one—in its various forms—that has resulted in actual and attempted losses of more than a billion dollars to businesses worldwide.

“BEC is a serious threat on a global scale,” said FBI Special Agent Maxwell Marker, who oversees the Bureau’s Transnational Organized Crime–Eastern Hemisphere Section in the Criminal Investigative Division. “It’s a prime example of organized crime groups engaging in large-scale, computer-enabled fraud, and the losses are staggering.”

Since the FBI’s Internet Crime Complaint Center (IC3) began tracking BEC scams in late 2013, it has compiled statistics on more than 7,000 U.S. companies that have been victimized—with total dollar losses exceeding $740 million. That doesn’t include victims outside the U.S. and unreported losses.

The scammers, believed to be members of organized crime groups from Africa, Eastern Europe, and the Middle East, primarily target businesses that work with foreign suppliers or regularly perform wire transfer payments. The scam succeeds by compromising legitimate business e-mail accounts through social engineering or computer intrusion techniques. Businesses of all sizes are targeted, and the fraud is proliferating.

According to IC3, since the beginning of 2015 there has been a 270 percent increase in identified BEC victims. Victim companies have come from all 50 U.S. states and nearly 80 countries abroad. The majority of the fraudulent transfers end up in Chinese banks.

Not long ago, e-mail scams were fairly easy to spot. The Nigerian lottery and other fraud attempts that arrived in personal and business e-mail inboxes were transparent in their amateurism. Now, the scammers’ methods are extremely sophisticated.

“They know how to perpetuate the scam without raising suspicions,” Marker said. “They have excellent tradecraft, and they do their homework. They use language specific to the company they are targeting, along with dollar amounts that lend legitimacy to the fraud. The days of these e-mails having horrible grammar and being easily identified are largely behind us.”

To make matters worse, the criminals often employ malware to infiltrate company networks, gaining access to legitimate e-mail threads about billing and invoices they can use to ensure the suspicions of an accountant or financial officer aren’t raised when a fraudulent wire transfer is requested.

Instead of making a payment to a trusted supplier, the scammers direct payment to their own accounts. Sometimes they succeed at this by switching a trusted bank account number by a single digit. “The criminals have become experts at imitating invoices and accounts,” Marker said. “And when a wire transfer happens,” he added, “the window of time to identify the fraud and recover the funds before they are moved out of reach is extremely short.”

In the case mentioned above—reported to the IC3 in June—after the accountant spoke to her CEO on the phone, she immediately reviewed the e-mail thread. “I noticed the first e-mail I received from the CEO was missing one letter; instead of .com, it read .co.” On closer inspection, the attachment provided by the “lawyer” revealed that the CEO’s signature was forged and the company seal appeared to be cut and pasted from the company’s public website. Further assisting the perpetrators, the website also listed the company’s executive officers and their e-mail addresses and identified specific global media events the CEO would attend during the calendar year.

The FBI’s Criminal, Cyber, and International Operations Divisions are coordinating efforts to identify and dismantle BEC criminal groups. “We are applying all our investigative techniques to the threat,” Marker said, “including forensic accounting, human source and undercover operations, and cyber aspects such as tracking IP addresses and analyzing the malware used to carry out network intrusions. We are working with our foreign partners as well, who are seeing the same issues.” He stressed that companies should make themselves aware of the BEC threat and take measures to avoid becoming victims (see sidebar).

If your company has been victimized by a BEC scam, it is important to act quickly. Contact your financial institution immediately and request that they contact the financial institution where the fraudulent transfer was sent. Next, call the FBI, and also file a complaint—regardless of dollar loss—with the IC3.

“The FBI takes the BEC threat very seriously,” Marker said, “and we are working with our law enforcement partners around the world to identify these criminals and bring them to justice.”

How to Avoid Becoming a Victim of a BEC Scam

In October 2013, the Internet Crime Complaint Center (IC3) began receiving complaints from businesses about about trusted suppliers requesting wire transfers that ended up in banks overseas—and turned out to be bogus requests. Since then, losses from the business e-mail compromise (BEC) scam have been significant.

“For victims reporting a monetary loss to the IC3, the average individual loss is about $6,000,” said Ellen Oliveto, an FBI analyst assigned to the center. “The average loss to BEC victims is $130,000.” IC3 offers the following tips to businesses to avoid being victimized by the scam (a more detailed list of strategies is available at www.ic3.gov):

- Verify changes in vendor payment location and confirm requests for transfer of funds.

- Be wary of free, web-based e-mail accounts, which are more susceptible to being hacked.

- Be careful when posting financial and personnel information to social media and company websites.

- Regarding wire transfer payments, be suspicious of requests for secrecy or pressure to take action quickly.

- Consider financial security procedures that include a two-step verification process for wire transfer payments.

- Create intrusion detection system rules that flag e-mails with extensions that are similar to company e-mail but not exactly the same. For example, .co instead of .com.

- If possible, register all Internet domains that are slightly different than the actual company domain.

- Know the habits of your customers, including the reason, detail, and amount of payments. Beware of any significant changes.

Resources:

- Public service announcement about the business e-mail compromise scam

- More about the IC3

- For more information about reporting or responding to business cyber attacks, read the U.S. Department of Justice publication Best Practices for Victim Response and Reporting of Cyber Incidents.