Attempted Extortion

Aspiring Actor’s New Role: Inmate

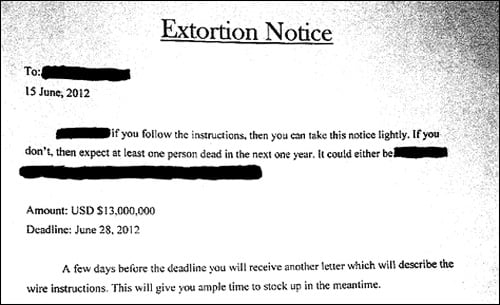

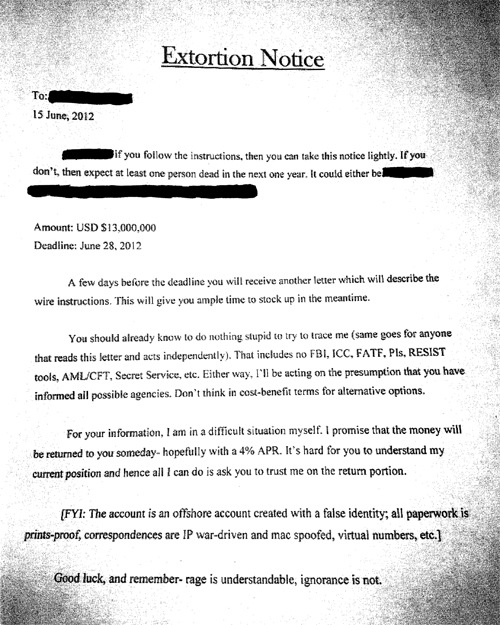

An excerpt of a letter from Vivek Shah, who attempted to extort more than $120 million from seven prominent victims.

It was an outrageous plan worthy of a Hollywood thriller. But an aspiring actor’s real-life attempt to extort tens of millions of dollars from wealthy targets earned him decidedly bad reviews in federal court and a new role for the next seven years—as a prison inmate.

Vivek Shah was pursuing an acting career in Los Angeles in 2012 when he thought of a better way to make money than from the bit parts he had landed in movies. He planned to extort billionaires—a coal tycoon and movie producer among them—by threatening to kill members of their families if they didn’t pay.

“He was very ambitious,” said Special Agent Jim Lafferty, who works out of our Pittsburgh Division and specializes in white-collar crime. Shah, 26, attempted to extort more than $120 million from seven prominent victims, including movie producer Harvey Weinstein ($4 million demanded), Groupon co-founder Eric Lefkofsky ($16 million demanded), coal executive Chris Cline ($13 million demanded), and oil and gas billionaire Terry Pegula ($34 million demanded).

He chose victims after doing online research about the world’s wealthiest people, and his targets were instructed to wire money to offshore bank accounts. To set up those accounts, Shah needed a proof of address, so he established a Post Office Box in Los Angeles using a fake driver’s license bearing the name Ray Amin.

“He had the fake ID created for the sole purpose of opening the PO Box,” Lafferty said. “He purchased it from someone who makes false IDs for underage college students.” Shah used various other means to avoid detection—like conducting online research from public places that provided anonymous Wi-Fi and using prepaid debit cards to purchase postage online for the extortion letters.

But things didn’t turn out as he planned. Shah had been involved in a domestic dispute with his roommate several weeks before he established the PO Box. When police were called to the scene in May 2012, they discovered the fake ID, which they checked against the FBI’s National Crime Information Center (NCIC) database. Shah told the officers he was an actor and that the bogus driver’s license was merely a prop. The NCIC check confirmed that no criminal activity was associated with the name Ray Amin.

Later, when agents discovered that “Ray Amin” had opened the PO Box connected with the extortion scheme, they ran their own NCIC check, and Shah’s name came back associated with Amin.

From there, agents were able to monitor Shah’s real online accounts, which led from California to Chicago, where video surveillance showed him mailing more extortion letters. The FBI Laboratory later matched his DNA with the letters. Shah was arrested in August 2012, pled guilty to the extortion scheme in May 2013, and was sentenced in September. Lafferty credits the U.S. Attorney’s Office for the Southern District of West Virginia with helping to bring the investigation to a quick and successful resolution.

After his arrest, Shah claimed his plan was to draw attention to himself. “He imagined the case going public and him gaining notoriety and somehow benefitting from that,” Lafferty said. “That obviously didn’t happen.”

Although the fake ID quickly led agents to Shah, Lafferty noted that the crime was ill-advised from the start. “The technology and investigative capability the FBI and our partners possess would make it extremely difficult to pull off an extortion scheme like this,” he said. “He really never had a chance.”