FBI Richmond History

1930s and 1940s

The FBI established a field office in Richmond in April 1937, led by Special Agent in Charge A. G. Berens. The first office was located in the Richmond Trust, Inc., building (now known as the Southern States building) at 7th and Main Streets. The original staff was comprised of a special agent in charge, a number of agents, a chief clerk, two stenographers, and one night clerk.

The new Richmond Division handled a wide range of criminal cases in its earliest years, from motor vehicle theft to kidnapping. With America’s entry into World War II in 1941, the division also began to tackle a greater number of national security matters. Even war-related criminal matters, though, could be deadly—and tragic. Working with local police in March 1942, Richmond Special Agents Hubert J. Treacy, Jr. and Charles L. Tignor identified and located two military deserters—Charles Joseph Lovett and James Edward Testerman. The two fugitives fired on the agents, seriously wounding Tignor and killing Treacy. Both deserters were quickly captured and later sentenced to life in prison.

Richmond agents soon faced another dangerous investigation as they pursued fugitive William “Two Gun Kinnie” Wagner, a famed trick-shot carnival worker who was reputed to have killed three law enforcement officers and two other men. Richmond agents located Wagner with the help of local police and arrested him on unlawful flight to avoid prosecution and kidnapping charges.

In May 1941, the Richmond Division received approval to open its first resident agency, or satellite office, in Roanoke. In December of that year, the Norfolk Division was established with investigative jurisdiction over eight counties in eastern Virginia and numerous military installations concentrated in the Tidewater area, all of which had previously been under Richmond’s jurisdiction.

Special Agent in Charge A. G. Berens

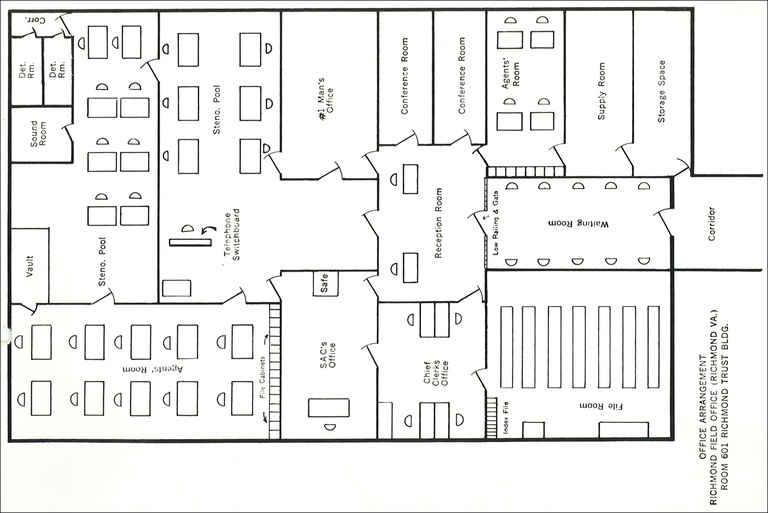

Floor plan of the Richmond field office in 1942.

1950s and 1960s

During the 1950s, a growing awareness of civil rights across the nation led to increasing investigative work for the Richmond Division. In late 1952, for example, the division began to probe the misuse of mail-in ballots in Russell County. Despite making progress in the face of local opposition, the FBI had its ballot evidence stolen from the Russell County Clerk’s Office, where it was held under court order, on the night of November 20, 1953. The Bureau stepped up its investigation, pursuing it for another year and ultimately developing enough evidence to indict several individuals.

In the 1960s, the division’s caseload continued to increase as it pursued more bank robberies and fugitive cases. New laws against racketeering and the interstate transportation of gambling equipment also helped the office tackle organized crime.

In 1962, the division rescued two young girls who were feared kidnapped. Missing for more than a day, Richmond agents re-canvassed the area where the girls had disappeared and found them simply locked in the bathroom of a vacant, neighboring apartment that management and others had supposedly searched. Tired and dehydrated, the girls were quickly united with their worried families.

The Richmond Division, which had jurisdiction over Northern Virginia at the time, pursued a number of espionage investigations during this period. In 1960, for example, agents arrested Arthur Roddey for attempting to compromise U.S. secrets. He pled guilty to the unauthorized possession of classified documents that could be used to the advantage of a foreign power. A year later, agents from the Alexandria resident agency learned that a naval contractor was trying to sell classified contract details to another man, who intended to peddle them to private entities hoping to have an inside track on acquiring those contracts. That led to the arrest of two people for theft of government property and misuse of classified information.

The division’s civil rights work continued in the 1960s. In 1965, under the newly-passed federal Voting Rights Act, Richmond investigators developed evidence to show that the poll tax of Virginia was unconstitutional. Agents interviewed hundreds of state election officials to help the U.S. Attorney build his eventually successful case. In 1966, division investigations led to the arrest of more than a dozen members of the United Klans of America, Inc. and the Knights of the Ku Klux Klan, significantly weakening those organizations. In 1970, agents investigated members of the Washington, D.C. chapter of the Black Panthers and an affiliate of the national party known as the Richmond Information Center for plotting to illegally transport weapons from Richmond to the nation’s capital. Division agents uncovered the scheme, leading to the conviction of four members of the two groups.

In December 1967, the Richmond office moved to the Farm Bureau Building, located at 200 West Grace Street. To address investigative matters in the six rapidly-growing counties of Northern Virginia previously covered by Richmond, the FBI established a field office in Alexandria, Virginia in May 1969.

Switchboard operator, 1967

Early Richmond division building

1970s and 1980s

In the 1970s and 1980s, the Richmond Division continued to handle a wide variety of investigations.

Between June and October 1974, 13 bank robberies took place around the city of Richmond. Bringing in help from the other offices, the division quickly solved 10 of the robberies.

Like other FBI field offices around the nation, Richmond also began expanding its undercover work during this time. In 1977, for example, its Bristol Resident Agency launched a short-term undercover operation targeting the distribution of illegal recordings. A special agent pretended to be an interested buyer, resulting in the arrest of nine people and the seizure of illegal bootlegs.

During the late 1970s, Richmond agents arrested a Pittsylvania County official involved in an interstate prostitution ring and identified two workers at the Surry Nuclear Power Plant who were sabotaging fuel rods stored there. The division also became the pilot office for the development of a new Bureau automation program called the Field Office Information Management System, or FOIMS—an early attempt to leverage computer databases to track FBI investigative work and draw intelligence from it.

In 1980, a Bristol agent looked into the theft of heavy construction equipment from local coal mining operations as part of a regional effort called the Leviticus Project that teamed up state and local law enforcement with the FBI to tackle coaling industry crime. The agent’s successful work led to deeper cooperation in a project named Genesis—a joint task force consisting of the FBI, the Virginia State Police, the ATF, and the IRS—which pursued leads from the earlier equipment theft investigations.

In January 1981, a Roanoke agent learned that two men were selling large quantities of frozen shrimp at prices well below wholesale. The agent quickly identified the salesmen. With the help of his colleagues in the division, he tracked their activities and learned of a stash of 356 cases of stolen shrimp and the trailer from which the shrimp had been taken. The trailer, it turned out, was linked to a stolen truck investigation in Washington, D.C. Its cab had been found abandoned in Montgomery County, Maryland, minus its trailer and contents. Leads had gone cold until the Roanoke discovery.

In March 1986, the Richmond Division set-up a toll-free hotline for Virginia citizens to call with tips about local and state political corruption.

On April 11, 1988, an FBI helicopter pilot was able to knock down Charles Leaf, II—a fugitive who was holding his wife and child hostage in Sperryville—with a gust of wind from the copter’s rotor. An FBI sharpshooter then fatally shot Leaf while he was separated from his hostages.

The division also had success in locating national fugitives. In 1981, through strong detective work, an agent located Richard Smause, a Richmond attorney who had fled prosecution for extortion eight years earlier. Based on the agent’s investigation, Chicago agents were able to immediately identify and arrest the fugitive. On June 1, 1989, agents arrested John Emil List in a Richmond suburb. List, wanted for the murder of his wife and children, had been a fugitive since 1971. The identification of List was aided by a tip generated from an episode of America’s Most Wanted that detailed the case.

In December 1989, the division moved a third time, relocating to 111 Greencourt Road. From this new space, the office pursued a wide variety of cases, including major drug operations. Within a few months of the opening of the new facility, for example, Richmond agents and city and state police arrested seven people, most from a single family, for operating a major heroin distribution ring. A year later, local police and special agents arrested Michael O. Munday, who had been sought by Florida authorities since 1986 on a variety of drug charges arising from his role as a distributor for a major Colombian drug cartel.

1990s

In the 1990s, cases continued to span a variety of offenses. In 1993, Richmond agents arrested Michael W. Welsh for peddling bootleg versions of Boy Scout activity patches at the Boy Scout National Jamboree in Fort A.P. Hill. In 1997, the Richmond Division joined its partners in using the FBI’s public website to ask that workers from three major cigarette plants consider reporting wrongdoing by their employers. The announcement read: “The FBI is seeking assistance from past or present tobacco company researchers, scientists, product development personnel, or manufacturing officials knowledgeable about the cigarette development and manufacturing process.” The effort was part of a wide-ranging investigation to determine if leaders in those companies were culpable in ignoring and downplaying safety concerns about the dangers of tobacco products.

Throughout the 1990s, the Richmond Division was also active in tracking down stolen historical memorabilia. In one major case, agents at a Civil War show in Richmond picked up the trail of two Pennsylvania men who had stolen $3 million worth of artifacts from the Historical Society of Pennsylvania. Over the course of the investigation, agents arrested Society officials who had been stealing objects from a museum storeroom for 10 years. More than 200 artifacts were recovered, including a lock of George Washington’s hair and the flintlock rifle that abolitionist John Brown used at the siege of Harper’s Ferry.

On February, 26, 2001, the Richmond Field Division officially commenced operations at 1970 East Parham Road.

Post-9/11

Following the events of 9/11 , the Richmond Division’s top priority—like other FBI field offices—became the prevention of terrorist attacks. It quickly stood up a Joint Terrorism Task Force to combine the skills and resources of local, state, and federal agencies. In 2003, the office also created a Field Intelligence Group to oversee the collection, analysis, production, and dissemination of intelligence on criminal and national security threats.

The division’s growing counterterrorism capabilities paid off in the investigation and successful conclusion of a domestic terrorism case. Between December 8, 2003 and January 12, 2004, three members of a cell of the radical environmental terrorism group known as the Earth Liberation Front (ELF) pled guilty to federal arson and conspiracy charges following their arrests by the Richmond Division and local authorities. The cell’s members were responsible for a series of arson and property destruction attacks in 2002 and 2003 against sport utility vehicles (SUVs), fast food restaurants, construction vehicles, and construction sites in the Richmond area. In addition, FBI Richmond—working in concert with the Henrico County Police Department—successfully prevented another arson plot targeting SUVs by a second, independent ELF cell in February 2004.

Meanwhile, the Richmond Division continued to address violent crime and other criminal threats. In August 2001, for example, agents arrested fugitive Dwight Bowen, who was accused of firebombing a North Philadelphia house, resulting in the deaths of two young boys and the injury of two adults. State and federal authorities had sought him for more than three months before he was captured. In April 2002, following a Richmond investigation, hate crime charges were filed in the 1996 murder of two female hikers in the Shenandoah National Forest. The murders of Julianne Marie Williams and Laura S. Winans had attracted national attention because the motive for the murders appeared to be the sexual orientation of the women. Darrell David Rice was charged with the murders under hate crime statutes.

With new intelligence capabilities, new and deepened cooperation with a variety of law enforcement and intelligence partners, and new post-9/11 legal authorities and resources, the Richmond Division is committed to continuing its work to protect local communities and the country from a range of national security and criminal threats.