FBI New Haven History

1940s and 1950s

The Bureau’s first field office in New Haven opened in the spring of 1940, as war in Europe was heating up and the FBI’s responsibilities were increasing. J.J. McGuire served as acting special agent in charge during its first year in operation.

Previously, FBI investigations in Connecticut were handled from Hartford—which operated as a division for two brief periods—or from the New York Field Office.

During its earliest years, the New Haven Division worked both federal crimes and major national security violations. Bank robberies and fugitive searches took up much of its time, but the office also investigated spies and Selective Service violators, conducted inspections of local wartime manufacturing plants’ security, and handled many other matters.

In 1945, Elizabeth Bentley—a courier for two Soviet spy rings in Washington, D.C.—turned herself in to the New Haven Division. Her initial report was convoluted and incomplete, as she tried not to implicate herself in serious national security violations, but she ultimately revealed a wealth of information about Soviet intelligence networks in Canada and America.

By the early 1950s, the division was working an increasing number of Atomic Energy Act cases, alien registration violations, Communist Party investigations, and extortion matters. And its work continued to grow. By 1957, FBI New Haven was handling 330 criminal investigations; 317 security matters; and 213 applicant and other types of cases. The office employed 46 agents and 29 support personnel.

Tragedy struck the New Haven Division that same year, when Special Agent Richard P. Horan was killed in the line of duty by fugitive Francis Kolakowski. Kolakowski had been charged with his wife’s murder and with bank robbery, but fled while awaiting trial. In April, agents tracked him to his sister’s house in Suffield. Horan was murdered by Kolakowski on the basement steps; the fugitive then turned his gun on himself and committed suicide.

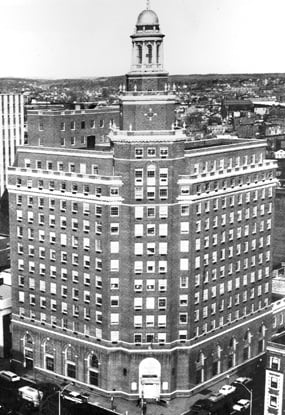

Early New Haven field office

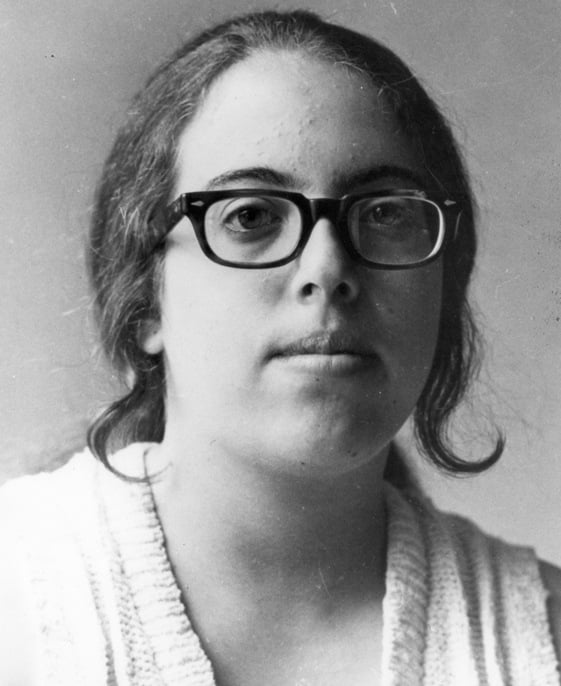

Susan Saxe

1960s and 1970s

In 1970, a body riddled with bullet holes, burns, and puncture marks was found floating in the Coginchaug River in Connecticut. FBI New Haven and local police learned that the victim was Alex Rackley, a member of the Black Panther Party who had been kidnapped, tortured, and murdered by other party members because they suspected he was an FBI informant. The ensuing investigation identified several Black Panther Party leaders as suspects. Two confessed to murder, and a third was convicted of conspiracy. Party founder Bobby Seale was believed to have ordered the killing; however, during his trial the jury deadlocked, and charges against him were dropped. Nevertheless, thousands of Black Panther Party supporters and radicals from other extremist groups descended on New Haven to demonstrate on behalf of the well-known Seale. For several days, these supporters set off bombs and threw rocks, while FBI agents worked with local authorities to quell the violence.

New Haven agents also continued to hunt down and arrest wanted fugitives. In 1969, the division worked with local police to locate Ten Most Wanted Fugitive Francis Hohimer in Cos Cob. Hohimer had ties to organized crime and was sought for the armed robbery of a philanthropist. He had also taken $57,000 in jewelry and cash at gunpoint. When New Haven agents caught up with him, he admitted he was “tired of running.” In 1978, the division joined local authorities in capturing another most wanted fugitive—Michael Thevis—in Bloomfield. Nicknamed the “pornography king,” Thevis had escaped a county jail but was arrested while trying to fraudulently cash a check using false identification. The division also played a significant role in helping the Philadelphia Division capture Top Tenner Susan Saxe—a radical who was wanted for bank robbery. FBI New Haven’s support included gaining crucial intelligence from a source.

By 1974, FBI New Haven’s personnel had grown to 91 agents and 57 support staff. The office was handling 1,534 criminal cases, 632 security matters, and 83 applicant and other investigations.

Some of these investigations involved major property theft, including a large stolen vehicle/chop shop conspiracy. An arson at the Sponge Rubber Company in Shelton also led to a major case. The fire caused more than $15 million in property damage and put hundreds of employees out of work. Before firebombing the place, masked perpetrators had kidnapped the guards (so no lives were lost) and hinted that they were extremists motivated by a political cause. As agents made inquiries, however, they soon uncovered a different motive—greed. Company management had taken out a $37 million “business interruption” insurance policy shortly before the fire. New Haven agents solved the case in record time, averting a huge insurance payoff and developing evidence to convict six culprits. The division did all this despite the massive crime scene—100 yards deep and four blocks long—which was processed by New Haven personnel and FBI Laboratory experts during freezing temperatures.

The division’s organized crime operations also increased in the 1970s. As mobsters based in New York and New England brought their rackets and illegal gambling operations into Connecticut, agents gathered clues and intelligence and made arrests when the evidence supported it.

1980s and 1990s

These early organized crime efforts were just the beginning. Members of several Mafia families continued operating in New Haven’s territory in the 1980s and 1990s. Armed with wiretap authority and stronger racketeering laws enacted in the 1970s, the division scored several major organized crime takedowns during these two decades.

The 1986 BACKLOG investigation, for example, led to the indictment of all Connecticut-based members of the Genovese crime family, including two “bosses.” In the GAMESTER case, the division went after the Gambino crime family. The arrest of 20 Gambino members in 1990 effectively dismantled the enterprise’s hierarchy and disrupted its racketeering activities across the state. At the same time, agents investigated the Patriarca criminal enterprise—penetrating its inner sphere and arresting 10 members across Connecticut in 1990. The attorney general and then-FBI Director William Sessions characterized the indictments as “the most sweeping attack ever launched on a single organized crime family.” Continued investigations over the next few years essentially evicted the Patriarca family from the state.

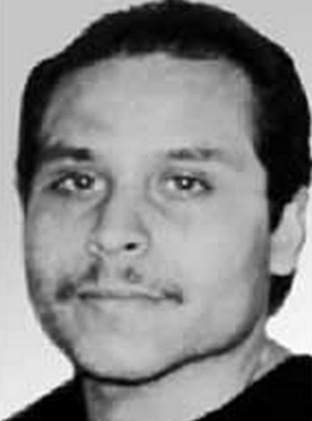

FBI New Haven continued to investigate fugitives and bank robbers and pursue major criminal enterprises. In West Hartford, for example, guard Victor Gerena helped rob a Wells Fargo armored car facility of $7 million in 1983—one of the largest cash heists at that time. The investigation revealed Gerena’s association with Los Macheteros—a Puerto Rican independence group linked to terrorist acts. Gerena was named to the Ten Most Wanted Fugitives list and remains wanted to this day. The investigation has led to the arrest of dozens of Gerena’s collaborators, including in recent years.

Another Top Ten fugitive—Wardell David Ford—was arrested following an episode of the America’s Most Wanted television show that described his crime and solicited tips on his whereabouts. Ford killed a guard while robbing an armored car company at gunpoint, taking $40,000. Agents apprehended him at his General Dynamics job in Groton in 1990.

The FBI’s field offices in New Haven and New York have always worked closely together, as their cases frequently overlap. Between 1980 and 2000, FBI New Haven assisted several major New York investigations, including NYROB—which tracked down extremists who robbed banks and committed violent acts—and cases involving the New Afrikan Freedom Fighters.

During the 1980s and 1990s, FBI New Haven also tackled increases in violent gang and illegal drug activities. Agents worked successful drug cases such as EXPRESSWAY, which probed money launderers linked to the Medellin Cartel; COLOMBAKE, an investigation into Colombian cocaine and heroin distributors and their money launderers; WATERBASE, which revealed a network of Jamaican crack cocaine traffickers in Waterbury; and CLONECANE, involving cocaine and heroin traffickers in New Britain. The division also investigated and arrested members of such as gangs the Hells Angels, the Jungle Boys, Los Solidos, and the Almighty Latin Charter Nation, a Connecticut offshoot of the Latin Kings gang. Top echelon convictions curbed the crime perpetrated by these gangs and sometimes led to the dismantling of the criminal groups.

In one significant case, the division pursued a violent enforcer for the Jamaican street gang called the Rats. O’Neil Vassell—a young member of the gang linked to several shootings and murders—was named to the Ten Most Wanted Fugitives list in 1995. The New Haven Division and the Connecticut Fugitive Task Force ran down all leads looking for this dangerous young man and got a break in 1996 when learning that someone named with his last name had been arrested in New York. Vassell had given his brother’s name as an alias when detained and was later released, but agents tracked down the arrest record, fingerprints, and photograph and finally apprehended O’Neil Vassell as he tried to escape through a Brooklyn apartment window.

Victor Gerena

During the 1990s, the division also investigated health care fraud. One major case—called Operation OVERDRAW—grew into a multi-agency, multi-state initiative. It targeted fraudulent testing practices in area laboratories and durable medical equipment suppliers who took kickbacks and falsely billed insurance carriers. The investigation was one of the most sophisticated and extensive operations of its kind at the time. Nearly 50 individuals were prosecuted, and agents seized 900 pieces of medical equipment valued at $1.3 million and recovered more than $21,000 in kickback money.

Post-9/11

Like the rest of the Bureau, the New Haven Division made significant changes to improve its ability to prevent terrorist attacks following the events of 9/11. It expanded its Joint Terrorism Task Force and re-engineered its intelligence operations, creating a Field Intelligence Group.

Guided-missile destroyer USS Benfold (DDG 65). U.S. Navy photo.

One investigation showcased these evolving capabilities. In 2003, British authorities investigated a man who was raising money online for Al Qaeda through a website hosted on Connecticut servers. They relayed intelligence to the FBI that a U.S.-born convert to Islam had expressed sympathy for Usama bin Laden and might be connected to Al Qaeda. FBI New Haven joined other divisions and Bureau intelligence partners in investigating this man. The suspect was a U.S. Navy signalman named Hassan Abu-Jihaad, who divulged classified military intelligence—including the locations and vulnerabilities of American naval ships—to Al Qaeda. His actions jeopardized the lives of his own shipmates and countless other naval personnel. The investigation uncovered a trail of Abu-Jihaad’s e-mails, showing how he praised the attack on the USS Cole and ordered extremist videos and other propaganda materials. Abu-Jihaad was ultimately convicted of supporting terrorism and revealing classified information about defense security. He was sentenced to 10 years in prison.

FBI New Haven continues to investigate all types of crimes—from cyber attacks to mortgage fraud, from illegal drugs to public corruption. In 2003, the division conducted a sensitive investigation of then-Connecticut Governor John G. Rowland. Rowland was a promising young politician who was being considered for a Bush administration position. During his third term, however, allegations emerged that contractors had worked on the governor’s lakeside cottage for free and that subordinates and businesses looking for deals with the state had given him gifts and discounted vacations. Reports also surfaced that he had bought into businesses just before they were granted state contracts. Rowland initially denied the allegations, but later admitted to the crimes. As the investigation proceeded, he announced his resignation as governor. In 2004, Rowland pled guilty to depriving the public of honest services.

In 2005, New Haven initiated Operation Phony Pharm, which targeted online pharmaceutical sales made without a doctor’s consultation or a prescription. The investigation also looked at underground laboratories producing drugs from raw materials obtained abroad. After launching its probe, FBI New Haven learned that the Drug Enforcement Administration was running a similar case with international dimensions. Sharing intelligence led to numerous arrests and seizures in both agencies’ cases.

In recent years, the division led a multi-agency investigation of the Mafia-controlled waste-hauling industry in Connecticut. For decades, trash haulers had claimed “permanent property rights” to accounts, insisting no other hauler could bid on them. These claims had no legal basis, but mob control meant that other haulers could not compete for the accounts—if they tried to bid on them, their drivers were assaulted and their equipment vandalized. Following New Haven’s investigation, more than 30 individuals and 10 companies pled guilty or were convicted in these schemes. The biggest offender was James Galante—owner of 25 trash companies—who was accused of using violent intimidation tactics, fixing bids, and instructing others to lie to the FBI and the grand jury. In 2008, Galante pled guilty to conspiracy to commit racketeering and to tax and wire fraud. On top of an 87-month prison sentence, Galante received a $100,000 fine and forfeited his ownership in the 25 companies, other personal property, and almost $500,000 in cash.

Heading into the FBI’s second century of service, the New Haven Division continues its work to protect Americans from domestic and international terrorism, espionage, cyber crime, and a range of other major crimes and national security threats.