FBI Indianapolis History

Special Agent in Charge Reed Vetterli

Early 1900s

The Bureau has had a presence in Indianapolis since its earliest years. By 1924, Indianapolis was functioning as a full division, headed by Special Agent in Charge E.L. Osborne and staffed by five special agents. At the time, however, the office was in an “unsettled condition,” and Bureau inspectors expressed concern about the “transience of agents” and other issues.

The Indianapolis Division closed in 1929, but reopened in May 1934 with Special Agent in Charge Reed E. Vetterli at its helm. The hunt for notorious gangster John Dillinger, although centered in Chicago, was a key focus of the new Indianapolis Division during this time. Dillinger was born and raised near Indianapolis, and his family still lived there. He had committed many crimes in the area and had hidden out in Indianapolis’ territory. Although the Bureau sought Dillinger on fugitive and automobile theft charges, Indiana police wanted him on the more serious charge of killing a police officer. For all these reasons, the work of the division was central to the Bureau’s top priority at that time—apprehending Dillinger. Dillinger was ultimately gunned down by Bureau agents in Chicago in July 1934.

On August 16, 1935, the division experienced its first tragedy. Special Agent Nelson B. Klein and another agent were seeking George W. Barrett, who was wanted for transporting stolen vehicles across state lines. The agents located Barrett near his brother’s hometown of College Corner and demanded his surrender. Barrett instead ran behind a garage and opened fire, mortally wounding Klein. Klein’s return gunfire, however, had struck Barrett in both legs, enabling his capture. Barrett was later convicted of Klein’s murder, becoming the first criminal to receive the death penalty under a new law that made killing a federal officer a capital offense.

1940s and 1950s

As America entered World War II, the type of investigations the Indianapolis Division handled changed dramatically. Indianapolis agents monitored “enemy aliens” and handled diverse national security matters—from providing plant security surveys for manufacturers to identifying saboteurs and tracking down Selective Service Act violators and other deserters.

Following the war, national security remained a top priority, with the Bureau investigating communist espionage and subversion and working cases resulting from the 1946 Atomic Energy Act.

The Bureau and its Indianapolis office grew rapidly to address the rising workload. The division’s cases increased from 303 in 1937 to 1,251 in 1947. Despite the emergence of the Cold War, criminal investigations began to rise, with agents working to track down motor vehicle thieves and bank robbers.

Because it had become a center of trade and travel in the Midwest, Indianapolis was often a crossroads for fugitives. This led to many cases for the division. In March 1950, the FBI launched its Ten Most Wanted Fugitives program. Among the charter members of the list was Henry Harland Shelton, who had kidnapped a man and forced the victim to drive him through a number of states. When division agents caught up with Shelton in Indianapolis on June 23, 1950, the fugitive drew a .45 caliber automatic pistol and fired. Agents returned fire, wounding Shelton and capturing him.

In early 1955, Palmer Julius Morset fled before his trial on charges of robbing a finance company and was named to the Top Ten fugitives list. The following year, Indianapolis agents tracked down Morset, who was working in the city as a mason. He was arrested without incident. Two years later, another Top Tenner—Ben McCollum—was captured by agents in his Indianapolis rooming house. McCollum had escaped from the Oklahoma State Penitentiary, where he had also killed a fellow inmate.

1960s and 1970s

FBI Indianapolis pursued more fugitives in the coming decade. In one month in 1965 alone, Indianapolis Special Agents Herbert Bradshaw and William Liston apprehended a remarkable eight fugitives.

Special Agent Nelson B. Klein

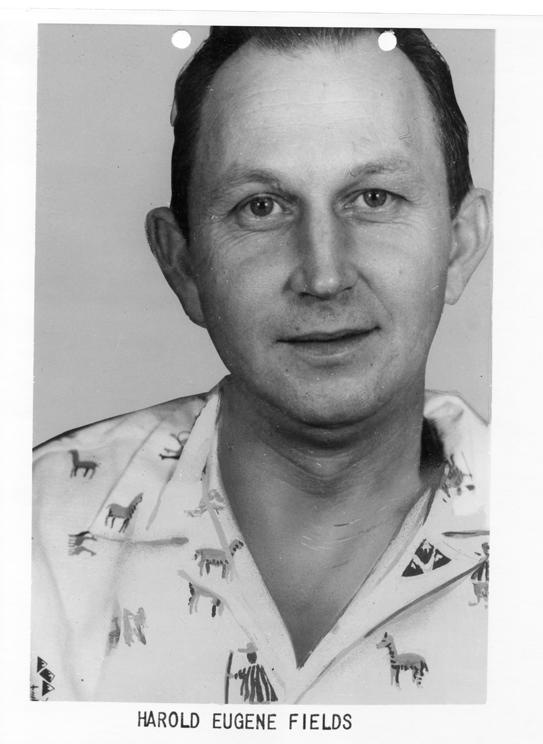

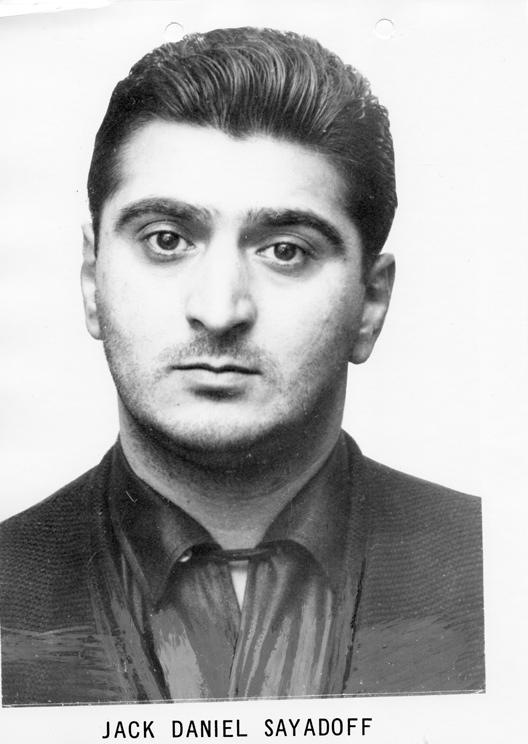

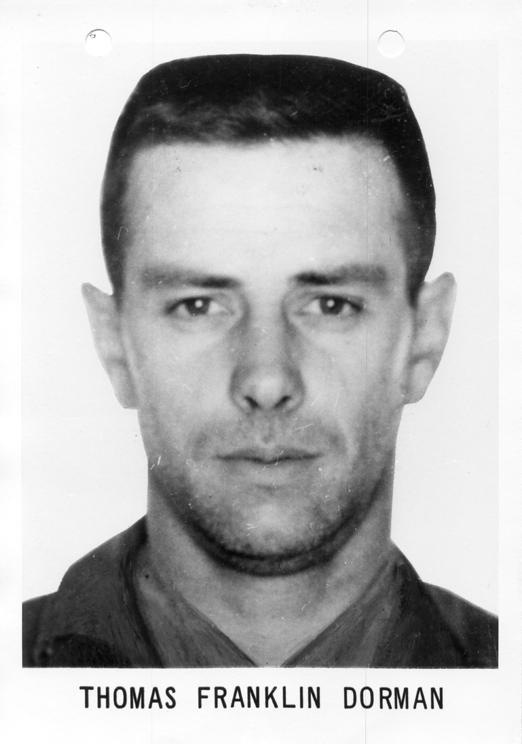

The office also arrested three more Top Ten fugitives. In May 1960, Harold Eugene Fields fled Illinois while appealing a burglary charge. Four months later, agents arrested him at a Schererville truck stop. Fields told them he knew his days of freedom were numbered when he made the list. In 1966, agents apprehended Jack Sayadoff, wanted for robbing a savings and loan in Chicago. The next year, Indianapolis agents and Indiana State Police caught Thomas Franklin Dorman in the woods near his parents’ home in Grantsburg. Dorman and a criminal colleague had robbed a supermarket and fled, with his accomplice shooting a police officer.

Harold Eugene Fields

Jack Sayadoff

Thomas Franklin Dorman

FBI Indianapolis handled various racketeering cases during the 1960s. Because of repeated federal raids in Illinois, several mob gambling enterprises relocated to Lake County, Indiana. In 1966, 60 Indiana and Chicago agents simultaneously raided three gambling joints and arrested dozens of suspects. The division also spent years monitoring Lake County crime syndicate boss Anthony Gruttadauro and Anthony Zizzo, who ran a Gary gambling business. Both were linked to the Chicago Mafia.

In 1968, the Baltimore and Ohio (B&O) Railroad received an anonymous letter threatening sabotage and demanding that $150,000 be dropped from a train at a named location. Indianapolis agents dressed as repairmen at the drop place, while another investigator threw a dummy money bag off the train at the appointed time. When the extortionist went to pick up the money, agents swooped in and caught him. Timothy Lee Allen was convicted of the crime. B&O executives later commented that FBI Indianapolis’ operation was “absolutely fantastic” and that they had “never seen anything so well organized.”

Between 1964 and 1974, the division grew substantially. In 1964, Indianapolis handled 1,355 criminal cases, 254 national security ones, and 368 other investigations. By 1974, a total of 130 agents and 71 support staff were involved in 2,522 criminal, 1,053 national security, and 93 other cases.

In the late 1970s, the FBI significantly revised the way it handled certain cases, drastically reducing the number of domestic security investigations. It began emphasizing undercover criminal work and the targeting and penetration of organized criminal enterprises. These changes led to continued investigative successes for the division.

In 1976, for instance, an Indianapolis agent investigating organized fencing operations in the state developed a relationship with a criminal informant. Using information from this source, the FBI and Indiana police opened a fake storefront and posed as fences in the largest joint law enforcement initiative of the time—Operation South Bend Fence. Undercover operatives made more than 400 buys of nearly a million dollars-worth of goods from thieves at a South Bend warehouse. Some 40 agents and 140 state and local officers closed the case in December 1976, arresting more than 50 subjects and indicting 50 more. Almost 600 local cases were developed on 149 local subjects.

In another sting called Operation Fountain Pen, an Indianapolis agent purchased a $50,000 fraudulent letter of credit from a pair of con men named Phillip Karl Kitzer and Paul Chovanec. Over time, Indianapolis agents ultimately discovered a loosely organized fraternity of swindlers and a Mafia figure involved in offshore banks, advance fee schemes, insurance frauds, and bankruptcy bust-outs. Fifty additional cases in 17 offices and various other countries developed from leads in Operation Fountain Pen. As a result of this investigation and others, the FBI began getting its arms around white-collar crime and built innovative databases to better track this national threat.

1980s and 1990s

Major violent crime—and related civil rights violations—were an important focus of the division in the early 1980s.

For example, on May 29, 1980, civil rights leader and National Urban League chairman Vernon Jordan, Jr., was walking with a white woman when he was wounded by sniper fire in a Fort Wayne parking lot. A few months later, avowed racist and serial killer Joseph Paul Franklin was arrested in Kentucky for armed robbery. A lead suggested that Franklin might be linked to the Jordan shooting. Indianapolis agents studied Franklin’s handwriting and found similar styles in alias signatures from motel registration cards. The FBI Laboratory corroborated the handwriting match; however, Franklin denied involvement and was acquitted of the charges. Nevertheless, 14 years later, Franklin admitted shooting Jordan.

In 1980, a black family residing in a predominantly white Muncie neighborhood was repeatedly harassed, and their home was firebombed to the point of being completely destroyed. A local grand jury was impaneled, but after two years local authorities advised the FBI that insufficient evidence existed to sustain a conviction. Under federal civil rights statutes, the Indianapolis Division went ahead and aggressively investigated. Although the division encountered significant obstacles, including reluctant witnesses, three subjects were convicted on multiple counts. The assistant attorney general for Civil Rights at the Department of Justice later praised FBI Indianapolis for its “tireless, intelligent, and courageous” efforts.

During the 1980s, Indianapolis continued to combat white-collar crime, financial crime, and public corruption. Partnering with the Internal Revenue Service and the Indiana State Police, the division investigated corruption in the Lake County Courts, where employees were fixing tickets of those who drove while intoxicated. This massive case took advantage of improving technical tools and growing skill in undercover operations and led to the conviction of a sitting judge for the first time in state history. Other judges, attorneys, and court representatives were indicted in the course of the investigation.

Recognizing the vulnerability of large events—especially those with international participation—to terrorist attack, the division built on the Bureau’s expertise developed in creating a Hostage Rescue Team in 1983 and heading up security at the 1984 Olympic Games in Los Angeles. When the Pan American Games and World Class Track Meet were held in Indianapolis in 1987, the office devoted significant staff and time to preparing for the security of these events. As groundwork, the FBI, Department of Energy, and Federal Emergency Management Administration conducted a training drill that simulated a terrorist deployment of a nuclear weapon.

In 1996, the U.K. government contacted the FBI for assistance when British Army Major David Nichols went missing while in the U.S. for training. Nichols’ rental car had been located near Terre Haute, sunken in a lake with the steering wheel wired to keep it from turning—foul play was obvious. Indianapolis agents were called in to investigate. They recovered from the automobile Nichols’ passport and a document with an Indiana address. The resident at this address had a relative, Roger Dale Yeadon, who had escaped from an Alabama prison. In the meantime, a suspicious junkyard owner reported two men had sold him a car for scrap metal. The car contained British pound notes and a letter describing Yeadon’s prison escape. Additional searches determined that a childhood friend of Yeadon resided in Indiana. FBI agents, a SWAT team, and Vigo County and Indiana State Police descended on the friend’s home, where they caught Yeadon. He confessed to shooting Nichols and burying him in the desert. The friend identified Yeadon’s partner in the crime as Michael Wayne Thompson, who was also captured. Yeadon and Thompson were returned to Alabama authorities.

Car theft rings ran rampant in Indiana for several decades. By the early 1990s, the state’s auto theft rate was twice the national average. FBI Indianapolis joined forces with the Indiana State Police, the Indianapolis Police Department, and the National Auto Theft Bureau to address this problem in the Mad Salvage case, targeting chop shops and the retagging of stolen motor vehicles. By the conclusion of the investigation in 1995, more than 30 subjects had been prosecuted federally and 20 locally. More than a million dollars of stolen property had also been recovered.

The division also saw increases in health care fraud and illegal drug investigations during the 1990s. In one significant case, Indianapolis agents investigated the Robinson Family, a group of cocaine and marijuana dealers who grew marijuana on a one thousand-acre farm. Other major drug trafficking cases included PENPOT, which focused on illicit drug traffic at the penitentiary at Terre Haute.

Post-9/11

Following the events of 9/11, Indianapolis joined the rest of the FBI in reorganizing its priorities—making preventing terrorist acts its primary mission. FBI Indianapolis strengthened its Joint Terrorism Task Force (JTTF), which had been established in 1999, and formed a Field Intelligence Group to enhance its collection and analysis of criminal and security information.

In one case, the Indianapolis JTTF investigated Frank Ambrose, a member of the Earth Liberation Front (ELF). ELF had claimed responsibility for spiking hundreds of trees with 10-inch nails in Indiana state forests over the years, posing a serious danger to anyone trying to cut down one of the trees. In 2001, the Indiana Department of Natural Resources arrested Ambrose, but the charge was dropped. Ambrose continued his criminal acts until 2009, when the JTTF investigation resulted in him being charged in Michigan for arson and property destruction. He pled guilty and was sentenced to nine years in prison and ordered to pay $4 million dollars in restitution.

In another case, the FBI Evansville Safe Streets Task Force assisted the Indianapolis and Evansville Police Departments, the Drug Enforcement Administration, and the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives in investigating Jarvis Brown. Brown was the ringleader of a group of violent cocaine and marijuana dealers. In 2005, he led his gang on a crime spree between Indianapolis and Evansville, committing a variety of murders, shootings, assaults, and robberies. The Indianapolis police apprehended the gang following a high-speed car chase on January 1, 2006. In March 2009, Brown pled guilty to a variety of charges. He was sentenced to five consecutive life terms, plus 20 years.

In the last few years, the division also investigated a couple who engineered a $23 million mortgage fraud scheme (see "Living the High Life" below) and a group of local police officers who were selling illegal drugs (see "A Few Bad Apples" below).

Post 9/11, FBI Indianapolis continues to investigate a wide range of national security matters and major crimes—from terrorism to espionage…from public corruption to mortgage fraud…from child pornography to organized crime. The Indianapolis Division remains committed to continuing its work to protect and defend its communities and the nation.

Living the High Life

Beverly Ross and Donella Locke liked the finer things in life. They lived in $250,000 homes and drove expensive vehicles. They also supported various family members. However, their lavish lifestyle eventually came crashing down around them.

In 2006, FBI Indianapolis received a tip that Ross was using third-party credit histories to fraudulently purchase high-priced homes in the Indianapolis area. Based on the tip—and working closely with several agencies—the FBI uncovered a fraud scheme involving mortgages valued at more than $23 million.

Ross and Locke, investigators learned, were preying on individuals through their church associations. They talked acquaintances into purchasing homes for other individuals who they described as “cash-rich but credit-poor.” These straw borrowers were led to believe they would hold the homes in their names until the true buyer could qualify for the loan. The straw borrowers were told that they didn't have to make any mortgage payments and that they would receive $10,000 for their trouble. What Ross and Locke were concealing was the fact that they were having the homes appraised at higher purchase prices than their actual value. The two submitted fake invoices for work to be completed from fake companies they controlled to skim the inflated equity from the homes.

Their scam didn't end there. These criminals also purchased several homes in their own names, using false social security numbers and inflated salaries and submitting false documentation on loan applications to obtain mortgages. Their scheme netted them $1.7 million.

FBI Indianapolis was able to put an end to their fraud. Working with multiple agencies, particularly the Indiana Attorney General's Office, agents diligently combed through public records, conducted interviews, and subpoenaed financial documents that clearly showed the extent of their crimes.

In 2008, Ross and Locke were indicted by a grand jury in the Southern District of Indiana on 36 counts of wire fraud and one count of conspiracy. Ross was also indicted for bankruptcy fraud for submitting Chapter 13 petitions in her family members’ names without their knowledge. Ross pled guilty and was sentenced to five years in prison and ordered to pay a restitution of $5.6 million. Locke was tried by a jury, which found her guilty of five counts of wire fraud. She received almost six years in prison and was ordered to make restitution of $2.36 million.

A Few Bad Apples

Americans should be able to trust their public servants to use their positions lawfully. That’s why crimes that breach this trust are our top criminal investigative priority.

While thousands of men and women serve the citizens of Indiana with honesty and integrity every day, their work is sometimes overshadowed by the occasional crooked public official. Three examples are former police officers Robert B. Long, Jason P. Edwards, and James D. Davis, who committed the types of crimes they were sworn to uphold.

Here’s how the Indianapolis Division and its partners brought these three men to justice.

In 2008, FBI Indianapolis received information from the Indianapolis Metropolitan Police Department (IMPD) that some of its narcotics officers might be involved in theft or distribution of illegal drugs. The FBI worked closely with IMPD and the Indiana State Police ( ISP) to verify the allegations and then build a case with corroborating evidence. Agents used a wide array of techniques along the way—records checks, physical surveillance, witness interviews, and court-ordered telephone monitoring.

Then investigators asked themselves: Who else might be involved, and how far would these officers go to betray their community? To find out, they developed an undercover sting, using an abandoned building as a fictitious drug stash house where cash and marijuana were stored. The officers took the bait, robbed the stash house, and split up the money. They didn’t realize, however, that FBI agents and officers form the IMPD and ISP were watching—until they were arrested along with their drug dealer. Long and Edwards were convicted on multiple drug charges and received prison sentences of 25 years and 17 years, respectively. Davis pled guilty and received 10 years in prison.

Solving this case sent a message that crookedness in government won’t be tolerated.