Vasilli Zubilin

On August 7, 1943, FBI Headquarters received an anonymous typewritten letter in Russian. Our interest was piqued, and we quickly translated the letter.

Talk about intrigue: the writer accused more than ten Soviet diplomats in the U.S. of being spies, including the Soviet Vice-Consuls in San Francisco and New York and the Second Secretary of the Soviet Embassy in Washington—Vasilli Zubilin.

The charges were hard to believe. The Russians—our country’s allies in World War II—spying on the U.S.?

At the time, we’d only just begun investigating the extent of Soviet operations here. Our resources were heavily dedicated to Axis espionage and sabotage cases.

Vasilli Zubilin in 1943

Now, this letter. What to make of it? Parts of it were strange and unbelievable, but other parts confirmed things we already knew or suspected. It was clear that its author was well versed in Soviet intelligence in the U.S. and credible.

For example, four months earlier, our agents had learned that Zubilin had spoken with—and slipped money to—a Communist Party official named Steve Nelson. Zubilin’s aim? To infiltrate a Berkeley, California, lab doing work for the Manhattan Project, America’s secret atomic bomb program. We passed what we learned about Zubilin’s spying to the War Department, which had primary investigative jurisdiction on the project. After the war ended, we would investigate other, more serious attempts to steal U.S. A-bomb secrets, but that’s another story.

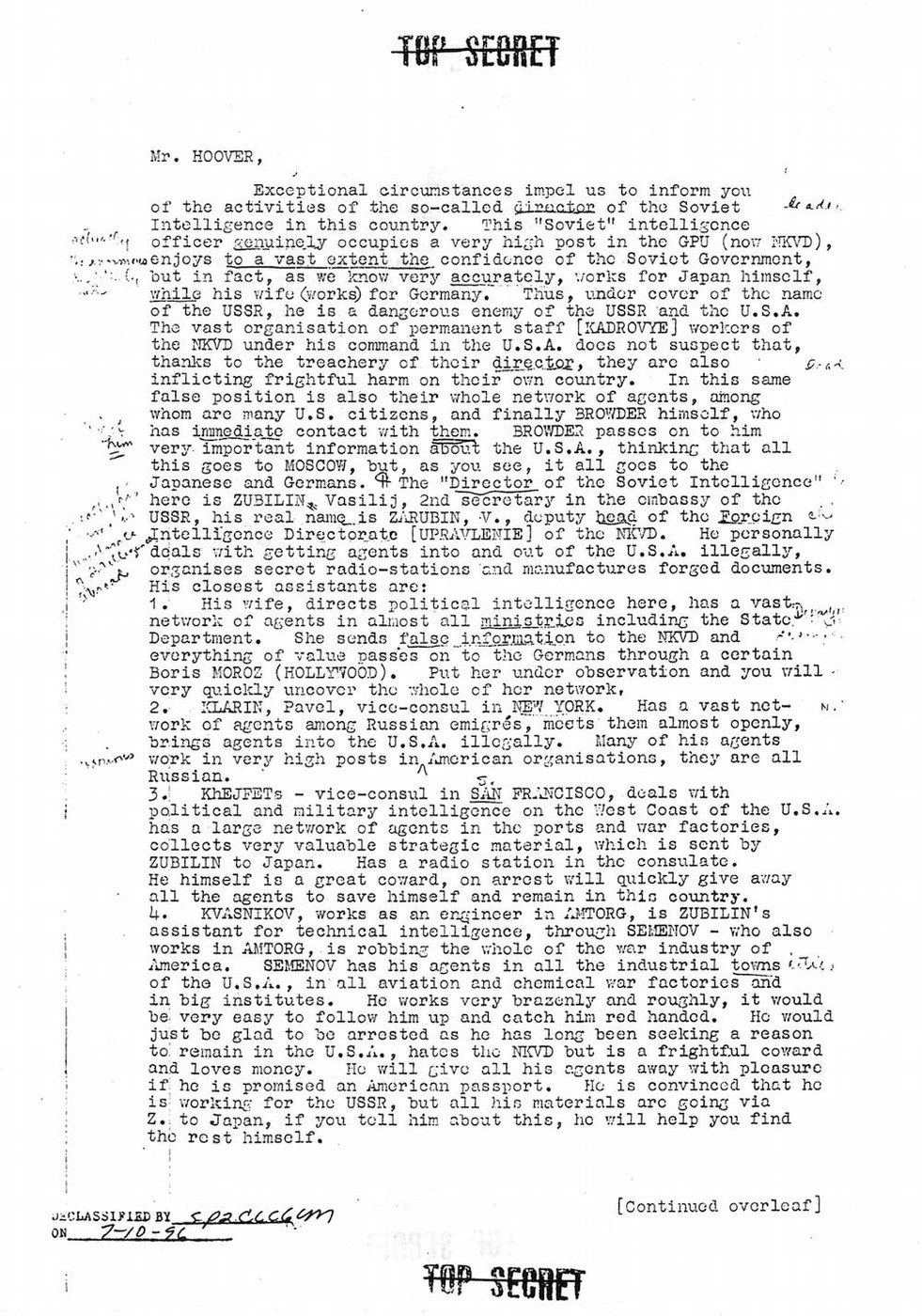

Mysterious letter that mentioned Vasilli Zubilin

In the meantime, we had a predicate to take a closer look at Soviet espionage. We launched a major investigation to discover the potential interrelationships of Soviet diplomats, the Communist Party of the United States, and the Communist International party, also called the “Comintern.” Through the case—called COMRAP, for “Comintern Appartus”—we learned that the extent of Soviet spying was significant.

The upshot? We were more prepared for the Cold War to come. In the next few years and beyond, the FBI and its intelligence partners identified hundreds of Soviet spies and helped protect vital American secrets from coast to coast.