Atom Spy Case/Rosenbergs

The Los Alamos National Laboratory, located in northern New Mexico, was launched in 1943 to design and build an atomic bomb for the United States. On July 16, 1945, the world's first atomic bomb was detonated 200 miles south of Los Alamos. The nation's bomb-making secrets were later stolen and passed to the Soviets. Photo courtesy of the Los Alamos National Laboratory.

The government of the Soviet Union, as it was then known, publicly announced the detonation of an atomic bomb in 1949.

Past experience taught Americans to treat Moscow pronouncements lightly. However, the White House, in a solemn statement on September 23 of that year, related the disheartening news which startled and shocked the nation.

The Kremlin had finally come to understand the secrets of the atom. Russian ingenuity in the scientific field probably contributed considerably to this discovery.

But what of the part played by American traitors Julius and Ethel Rosenberg? This is their story.

Klaus Fuchs was a member of a British team working with Americans on development of the atom bomb in Los Alamos. Arrested in England in 1950, he was convicted and sentenced to 14 years, the maximum penalty under the British Official Secrets Act.

Investigation Launched

In the summer of 1949, the FBI learned that the secret of the construction of the atom bomb had been stolen and turned over to a foreign power.

An immediate investigation was undertaken which resulted in the identification of Emil Julius Klaus Fuchs, a German-born British atomic scientist. British intelligence authorities were advised, and Fuchs was arrested by British authorities on February 2, 1950. He admitted his involvement in Soviet atomic espionage, but he did not know the identity of his American contact.

This contact was subsequently identified through FBI investigation as Harry Gold, a Philadelphia chemist. On May 22, 1950, Gold confessed his espionage activity to the FBI.

Investigation of Harry Gold’s admissions led to the identification of David Greenglass, a U.S. Army enlisted man and Soviet agent, who had been assigned by the Army to Los Alamos, New Mexico in 1944 and 1945. Gold stated that he had picked up espionage material from Greenglass during June 1945 on instructions of “John,” his Soviet principal. “John” was subsequently identified as Anatoli Yakovlev, former Soviet vice-consul in New York City, who left the United States in December 1946.

Interrogation of Greenglass and his wife, Ruth, resulted in admissions of espionage activity under the instructions of Julius and Ethel Rosenberg, brother-in-law and sister, respectively, of David Greenglass.

Max Elitcher, a naval ordnance engineer and an admitted communist, was interviewed. He disclosed that Morton Sobell, radar engineer and former classmate of Elitcher and Rosenberg at a college in New York City, was also involved in the Rosenberg espionage network.

Background of Principal Subjects

Julius Rosenberg was born on May 12, 1918 in New York City, the son of immigrants, both of whom were born in Russia. He had one brother and three sisters.

Ethel Rosenberg, nee Greenglass, was born September 28, 1915 in New York City, the daughter of immigrants. Her father was born in Russia, and her mother was born in Austria. Other members of her family included David, Bernard, and a half brother.

Ethel and Julius Rosenberg were married June 18, 1939 in New York City and had two sons, Micahel Allen, born March 10, 1943, and Robert Harry, born May 14, 1947.

Julius and Ethel Rosenberg lived in the lower east side of Manhattan most of their lives and both attended the same high school, Ethel graduating in 1931 and Julius graduating in 1934. Julius Rosenberg attended the school of engineering at a New York college from September 1934 until February 1939, when he graduated with a bachelor’s degree in electrical engineering. He also took various courses at other New York universities.

At the time of his apprehension he was operating a machine shop in New York City manufacturing all types of parts for various manufacturing concerns.

Investigation revealed that Julius Rosenberg began associating with Ethel Greenglass around 1932. Julius was disliked by Ethel’s parents and was not allowed to visit her parents’ home from about 1932 until 1935.

During that period Ethel and her two younger brothers, Bernard and David, occupied an apartment on a floor above the home of their parents. Julius Rosenberg would visit Ethel frequently at this upstairs apartment, which was littered with copies of Communist Party literature and The Daily Worker. Julius and Ethel became devoted communists between 1932 and 1935, after which they maintained that nothing was more important than the communist cause.

Information obtained in March 1944 reflected that Julius Rosenberg was a member of the Communist Party. This information was furnished to the Security and Intelligence Division, Second Service Command, Governors Island, New York, in view of Rosenberg’s employment by the War Department at that time. This investigation also established that his wife, Ethel, had signed a Communist Party petition. Rosenberg’s position with the U.S. government was terminated in December 1945.

A search of the Rosenberg apartment at the time of the arrest of Julius Rosenberg disclosed that Ethel and Julius Rosenberg were members of the International Workers Order.

In May 1940, the FBI’s New York Field Office learned, after Ethel Rosenberg received an appointment as an employee of the Census Bureau in Washington, D.C., that she was a devout communist. Further, Ethel Rosenberg and another woman, alleged to have been communist sympathizers, had distributed communist literature and and signed nominating petitions of the Communist Party. Ethel Rosenberg had also signed a Communist Party nominating petition, dated August 13, 1939, in New York City.

Investigation reflected that Julius Rosenberg claimed to have joined the Young Communist League when he was 14 years of age. Also, he was secretary of the Young Communist League while in college.

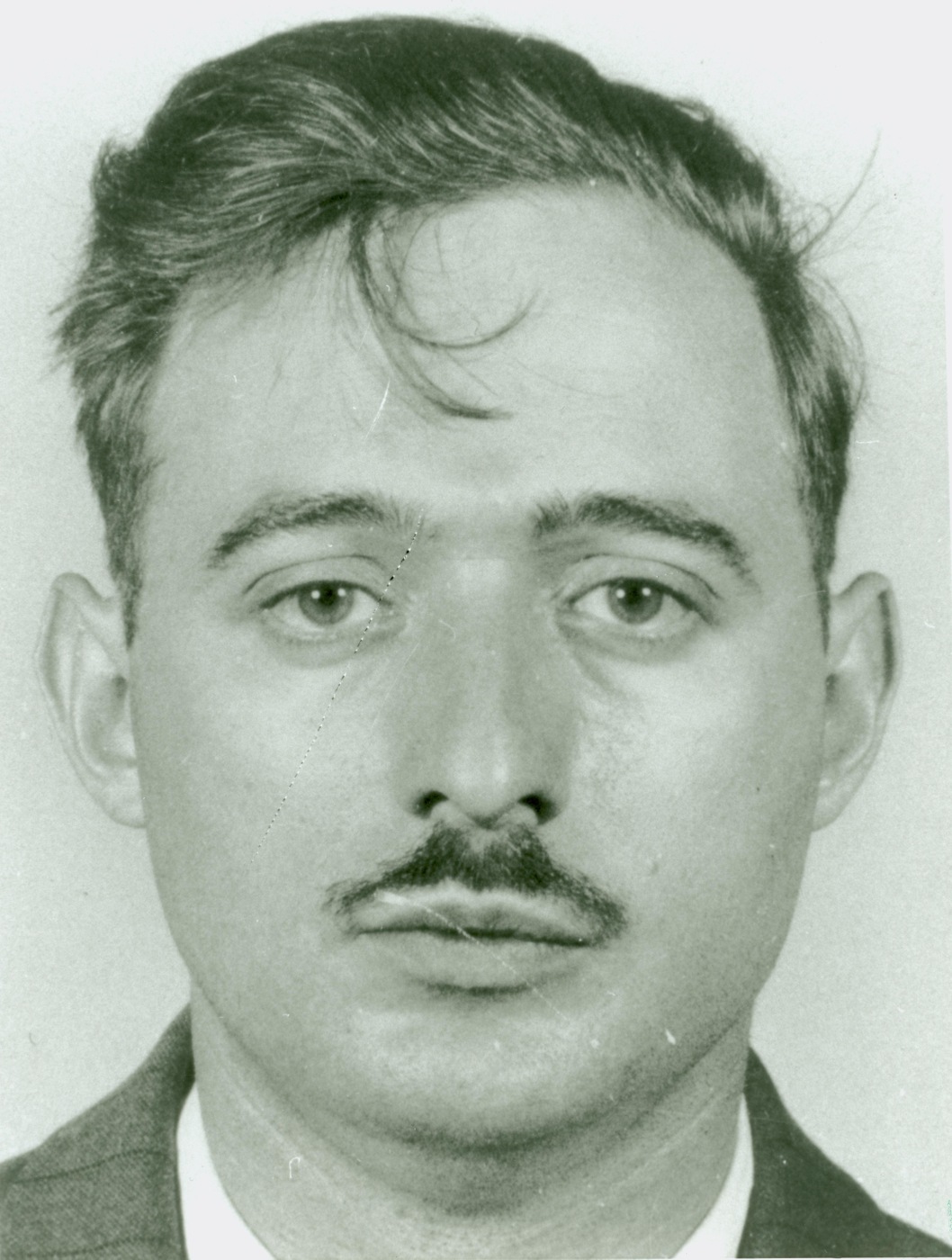

Julius Rosenberg

Ethel Rosenberg

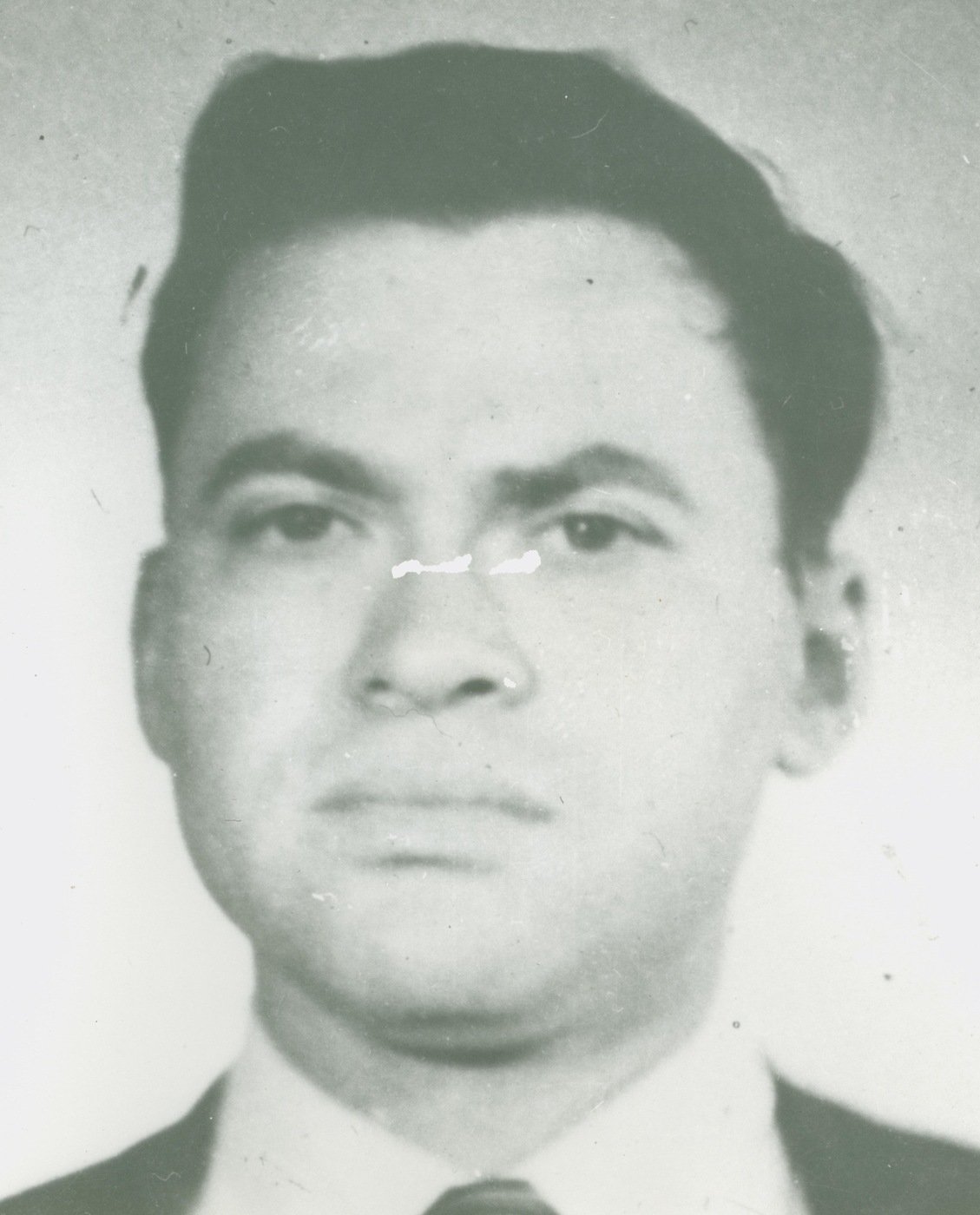

David Greenglass

David Greenglass, younger brother of Ethel Rosenberg, was born on March 3, 1922 in New York, where he attended public schools. After graduating from high school in 1940, he began attending college for a short period, studying mechanical engineering. He attended another school for a short period in 1948, studying mechanical designing. While he was young, he worked in his father’s shop.

David Greenglass

David Greenglass reportedly had come under the influence of his sister when he was about 12 years old and when the 19-year-old Ethel was being courted by Julius Rosenberg. At first, David opposed the efforts of Ethel and Julius to convert him to communism and disliked Julius, but after Julius brought David a chemistry set, the two became very friendly and Julius was able to influence David considerably.

Julius Rosenberg, until he married Ethel in 1939, continued to be a frequent visitor at David and Ethel’s apartment. David became extremely fond of Julius. Having become fully converted to Communist ideals expounded by Ethel and Julius, David joined the Young Communist League at the age of 14.

David Greenglass had admitted that he was indoctrinated with communist principles in his youth by Julius and Ethel Rosenberg and was a member of the Young Communist League in New York from 1936 to 1938. He continued his belief in communism, but never joined the Communist Party.

He claimed to have become disillusioned with communism when Marshal Tito of Yugoslavia was expelled from Cominform, the Communist Information Bureau created to share information among communist parties, for defying Soviet supremacy. This incident, he said, brought home to him that communism was being used as a tool by the Soviet Union for the purpose of world conquest instead of a means of reaching a panacea.

Soon after her marriage to Julius Rosenberg, Ruth Greenglass Rosenberg claimed she was converted to the principles of communism by her husband. A member of a branch of the Young Communist League for about one year in 1943 and president of that branch for about three weeks, she reportedly became disillusioned with communism following World War II, when it became apparent that Russia had embarked on a program of world conquest.

Morton Sobell

Morton Sobell was born the son of Russian-born immigrants on April 11, 1917 in New York City. He married Helen Levitov Gurewitz in Arlington, Virginia on March 10, 1945.

A classmate of Julius Rosenberg and Max Elitcher, Sobell graduated from college in June 1938, with a bachelor’s degree in electrical engineering. In 1941 and 1942 he attended a graduate school at a university in Michigan, from which he received a master’s degree in electrical engineering.

Sobell was employed during the summers of 1934 through 1938 as a maintenance man at Camp Unity, Wingdale, New York, reportedly a communist-controlled camp. On January 27, 1939, he secured the position of junior electrical engineer with the Bureau of Naval Ordnance, Washington, D.C. and was promoted to the position of assistant electrical engineer. He resigned from this position in October 1940 to further his studies.

While employed at an electric company in New York state, he had access to classified material, including that on fire-control radar. After resigning from this company, he secured employment as an electrical engineer with an instrument company in New York City, where he had access to secret data. He remained in this position until June 16, 1950, when he failed to appear at work. On that date, Sobell and his family fled to Mexico. He was subsequently located in Mexico City. On August 18, 1950, after his deportation from Mexico by the Mexican authorities, he was taken into custody by FBI agents in Laredo, Texas.

Max Elitcher, an admitted communist, said that in 1939, when he roomed with Morton Sobell in Washington, D.C., Sobell induced him to join the Communist Party.

Sobell was reported to have been active in the American Peace Mobilization and the American Youth Congress, both of which were cited by the attorney general as coming within the purview of Executive Order 10450. Sobell also appeared on the active indices of the American Peace Mobilization and was listed in the indices of the American Youth Congress as a delegate to that body from the Washington Committee for Democratic Action.

A resident of an apartment building in Washington, D.C., reported that Sobell and Max Elitcher were among those who attended meetings in the apartment of one of the tenants during 1940 and 1941. This individual believed that these were communist meetings.

Morton Sobell

The FBI’s New York Field Office located a Communist Party nominating petition that was filed in the name of Morton Sobell. The signature on this petition was identified by the FBI Laboratory as being in Sobell’s handwriting.

Contact with the instrument company where Sobell was employed showed that he failed to report for work after June 16, 1950. The company received a letter from Sobell on or about July 3, 1950, stating that he needed a rest and was going to take a few weeks off to recuperate. A neighborhood investigation by the FBI revealed that Sobell, his wife, and their two children were last seen at their home on June 22, 1950, and that they had left hurriedly without advising anyone of their intended departure.

Through an airlines company at La Guardia Field, it was determined that Sobell and his family had departed for Mexico City on June 22, 1950. Round-trip excursion tickets for transportation between New York City and Mexico had been purchased on June 21, 1950 in Sobell’s name.

During Sobell’s stay in Mexico, he communicated with relatives through the use of a certain man as a mail drop. This man was interviewed and reluctantly admitted receiving and forwarding letters to Sobell’s relatives. This admission was made after he was advised that the FBI Laboratory had identified his handwriting on the envelopes used in forwarding letters to Sobell’s relatives.

In August 1950, the Mexico authorities took Sobell into custody and deported him as an undesirable alien. On the early morning of August 18, 1950, FBI agents apprehended Sobell at the International Bridge in Laredo, Texas.

Armed with the information supplied by a man named Harry Gold, the FBI moved swiftly to bring to justice those responsible for stealing secrets of the U.S. government.

Authorities File Charges

On June 16, 1950, the Criminal Division of the Justice Department was advised of David Greenglass’s admissions and authorized the filing of a complaint in Albuquerque, New Mexico, charging him with espionage conspiracy to violate Title 50, U.S. Code, Section 34. On the same date, Greenglass was arraigned before a U.S. Commissioner of the Southern District of New York and was remanded to the custody of a U.S. marshal in default of $100,000 bail. On July 6, 1950, Greenglass was indicted by a federal grand jury in Santa Fe, New Mexico and charged with espionage conspiracy.

A complaint charging Julius Rosenberg with espionage conspiracy was filed on July 17, 1950. Rosenberg was arrested at his home in Knickerbocker Village, New York City, the same day and was arraigned that evening before a U.S. District judge, Southern District of New York. Rosenberg was remanded to the custody of the U.S. marshal in default of $100,000 bail for further hearing.

On August 3, 1950, the U.S. Attorney, Southern District of New York, authorized the filing of a sealed complaint against Morton Sobell, charging him with espionage conspiracy.

On August 7, 1950, Ethel Rosenberg appeared before a federal grand jury in the Southern District of New York pursuant to a subpoena. A complaint charging her with espionage conspiracy was filed on August 11, 1950. Ethel Rosenberg was taken into custody on the same day by FBI agents. Later, on the afternoon of August 11, 1950, she was arraigned before the U.S. Commissioner of the Southern District of New York and remanded to the custody of the U.S. marshal, in default of $100,000 bail for further healing.

On August 17, 1950, a federal grand jury in the Southern District of New York returned an indictment alleging 11 overt acts. Julius Rosenberg, Ethel Rosenberg, and Anatoli Yakovlev were charged with violation of Title 50, U.S. Code, section 34.

Following Morton Sobell’s August 18, 1950 arrest by FBI agents in Laredo, Texas, he was arraigned before the U.S. Commissioner, Southern District of Texas, waived removal to New York and was remanded to the custody of the U.S. marshal on August 23, 1950.

The Rosenbergs were arraigned before a U.S. District judge, Southern District of New York, and entered pleas of not guilty on August 23, 1950. Bail in the amount of $100,000 was continued for both of them.

The next day, Morton Sobell was arraigned before the U.S. Commissioner, Southern District of New York, and his hearing was adjourned. Bail of $100,000 was continued. On September 18, 1950, Sobell again appeared for a hearing before the U.S. Commissioner, which was adjourned to enable the government to present its case to a federal grand jury.

Anatoli Yakovlev was the general consul of the Soviet mission in New York City and a senior intelligence agent/Soviet handler of the A-Bomb spies, including Fuchs, Sobell, and the Rosenbergs.

On October 10, 1950, a superseding indictment was returned by a federal grand jury in the Southern District of New York. Morton Sobell, Ethel Rosenberg, Julius Rosenberg, David Greenglass, and Anatoli Yakovlev were charged with conspiracy to violate the espionage statutes.

On October 17, 1950, Julius and Ethel Rosenberg pleaded not guilty. Bail of $100,000 was continued for Julius Rosenberg; Ethel Rosenberg’s bail was reduced to $50,000. They were remanded to the custody of the U.S. marshal in default of bail.

David Greenglass pleaded guilty to the superseding indictment on October 18, 1950. His plea was accepted by the presiding judge, and bail of $100,000 was continued pending sentencing.

Morton Sobell entered a plea of not guilty on December 5, 1950. His plea was accepted by a U.S. District judge, Southern District of New York, and his bail was continued in the sum of $100,000.

On January 31, 1951, a federal grand jury handed down a second superseding indictment charging Julius Rosenberg, Ethel Rosenberg, Anatoli Yakovlev, Mortin Sobell, and David Greenglass with conspiracy to commit espionage between June 6, 1944, and June 16, 1950. This indictment was similar in all respects to the previous superseding indictment, except that it changed the start of the conspiracy from November 1944 to June 1944.

On February 2, 1951, Julius and Ethel Rosenberg and Morton Sobell entered pleas of not guilty before a U.S. District judge, Southern District of New York. David Greenglass entered a guilty plea to the above indictment and withdrew his plea of guilty to the previous superseding indictment. The judge directed that Greenglass’s sentencing be postponed until the end of the trial.

Morton Sobell applied for a writ of habeas corpus on February 5, 1951, claiming the indictment of January 31, 1951, was vague and that his incrimination was a violation of his constitutional rights. The application was denied.

The Trial Begins

On March 6, 1951, the Rosenbergs-Sobell espionage conspiracy trial on the superseding indictment of January 31, 1951, commenced in the Southern Distict of New York. At the outset of the case the U.S. Attorney moved to sever Anatoli A. Yakovlev from the trial, and the motion was granted. The selection of a jury of 12 with two alternates was completed on March 7, 1951. Counsel for the defendants made motions to dismiss the indictment on various grounds, which were denied by the court. A motion was then made and granted to sever David Greenglass from the indictment because he had already pleaded guilty.

Some of the espionage activities of the Rosenbergs with their ramifications were brought out at the trial of the atom spies. Greenglass’s testimony revealed that he entered the U.S. Army in April 1943 and in July 1944 was assigned to the Manhattan Project in Oak Ridge, Tennessee. He did not know at that time what the project was but he received security lectures about his duties and was told it was a secret project. Two weeks later, again being told that his work was secret, he was assigned to Los Alamos, New Mexico and reported there in August 1944.

In November 1944, his wife, Ruth Greenglass, who came to Albuquerque to visit him, told him that Julius Rosenberg advised her that her husband was working on the atom bomb. Greenglass stated that he did not know that he was working on such a project. He stated that he worked in a group at Los Alamos under a professor of a New England university and described to the court the duties of his shop at Los Alamos. He stated that while at Los Alamos, he learned the identity of various noted physicists and their cover names.

Greenglass testified that the Rosenbergs used to speak to him about the merits of the Russian government. He stated that when his wife came to visit him at Los Alamos on November 29, 1944, she told David that Julius Rosenberg had invited her to dinner at the Rosenberg home in New York City. At this dinner Ethel told Ruth that they had not been engaging in Communist activities, buying The Daily Worker any more, or attending club meetings because Julius finally was doing what he always wanted to do, which was giving information to the Soviet Union.

After Ethel told Ruth that David was working on the atom bomb project at Los Alamos, and said that she and Julius wanted him to give information concerning the bomb, Ruth told the Rosenbergs that she did not think it was a good idea and declined to convey their requests to David. Ethel and Julius remarked that she should at least tell David about it and see if he would help. During this conversation, Julius pointed out to Ruth that Russia was an ally and deserved to obtain the information that was not being provided for its use.

At first, David refused to have anything to do with the Rosenbergs’ request, but on the next day he agreed to furnish any available data. Ruth then asked David specific questions about the Manhattan Project and David gave her that information.

In January 1945, David arrived in New York City on furlough, and about two days later Julius Rosenberg came to David’s apartment to ask him for information on the A-bomb. He requested David to write up the information and said he would pick it up the following morning.

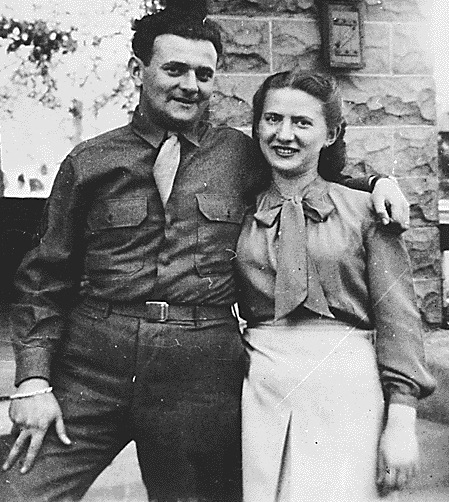

David and Ruth Greenglass. National Archives photograph.

That evening Greenglass wrote up the information he had. The next morning he gave this material to Rosenberg, along with a list of the scientists at Los Alamos and the names of possible recruits working there who might be sympathetic to communism.

Greenglass further stated that at the time he returned this material over to Rosenberg, Ruth Greenglass remarked that David’s handwriting was bad and would need interpretation. Rosenberg answered that it was nothing to worry about because Ethel, his wife, would retype the information.

A day or two later David and his wife went to the Rosenberg apartment for dinner where they were introduced to a woman friend of the Rosenbergs. After she left, Julius told the Greenglasses that he thought this person would come to see David to receive information on the atom bomb. They discussed a tentative plan wherein Ruth Greenglass would move to Albuquerque; this woman would also meet Ruth in a movie theater in Denver, Colorado to exchange purses. Ruth’s purse would contain the information from David concerning Los Alamos.

To identify the person who would come to see Ruth, it was agreed that Ruth would use a side piece of a Jello box. Julius held the matching piece of the Jello box. David suggested that meeting be held in front of a certain grocery store in Albuquerque. The date of the meeting was left to depend upon the time that Ruth would depart for Albuquerque.

During this visit, Julius said that he would like to have David meet a Russian with whom he could discuss the project on which David was working. A few nights later Julius made an appointment for David to meet a Russian on First Avenue between 42nd and 59th streets in New York City. David drove up to the appointed meeting place and parked the car near a saloon in a dark street. Julius came up to the car, looked in, went away, and came back with a man who got into David’s car. Julius stayed on the street, and David drove away with the unknown man. The man asked David about some scientific information, and after driving around for a while, David returned to the original meeting place and let the man out. This man was then joined by Rosenberg, who was standing on the street, and David observed them leaving together.

In the spring of 1945, Ruth Greenglass came to Albuquerque to live, and David visited her apartment on weekends. On the first Sunday of June 1945, a man, subsequently identified by David as Harry Gold, came to visit him and asked if David’s name was Greenglass. David said that it was, and Gold then said, “Julius sent me.” David went to his wife’s wallet and took out the piece of the Jello box and compared it with the piece offered by Gold. They matched.

When Gold asked David if he had any information, Greenglass said that he did but would have to write it up. Gold then left, stating he would be back. David immediately started to work on a report, made sketches of experiments, wrote up descriptive material regarding them, and prepared a list of possible recruits for espionage. Later that day Gold returned and David gave him the reports. In return, Gold gave David an envelope containing $500, which he turned over to Ruth.

The Court accepted copies of the sketches prepared by Greenglass at the time of the trial to describe the information Greenglass had turned over to Gold. These sketches were admitted into evidence.

In September 1945, David Greenglass, who was on furlough, returned to New York City with Ruth. The next morning Julius Rosenberg came to the Greenglass apartment and asked what David had for him. David informed Julius that he had obtained a pretty good description of the atom bomb.

At this point in Greenglass’s testimony the government prosecutor reverted to Rosenberg’s contact with David in January 1945. David reiterated that in January 1945, Rosenberg gave him a description of an atom bomb, which David later learned had been subsequently dropped on Hiroshima, in order that David would know what information to look for.

Greenglass continued to relate what transpired in September 1945. At Julius’ request, he drew up a sketch of the atom bomb, prepared descriptive material on it, drew up a list of scientists and possible recruits for Soviet espionage and thereafter delivered this material to the Rosenberg apartment. He stated that at the time he turned this material over to Rosenberg, Ethel and Ruth.

At the trial, Greenglass prepared a sketch of a cross section of an atom bomb to indicate what he gave to Rosenberg, an this was made government exhibit #8. At this point, Rosenberg’s lawyer asked the court to impound the sketch of the bomb so that no one but the court, jury defendants, and attorneys would be able to see it. Rosenberg’s lawyer stated the he was making this request in the interest of national security. The judge ordered the sketch impounded, pointing out that, inasmuch as the defense requested it, the defense would have no grounds for objection to the impounding in case of an appeal.

Greenglass then continued his testimony as to the composition of the atom bomb, using the sketch for reference. He stated that he told Rosenberg how the bomb was set off by a barometric pressure device. Rosenberg remarked that the information was very good and it should be typed immediately. Ethel then prepared the information on a portable typewriter in the Rosenberg apartment.

While Ethel was typing the report, Julius burned the handwritten notes in a frying pan, flushed them down a drain, and gave David $200. Julius suggested that David stay at Los Alamos after he was discharged from the Army so that he could continue to get information, but David declined.

From 1946 to 1949, David was in business with Julius Rosenberg, and during this period Julius told David that he had people going to school and that he had people in upstate New York and Ohio giving him information for the Russians.

Late in 1947, Julius told David about a sky platform project and mentioned he had received this information from “one of the boys.” Rosenberg described the sky platform as a large vessel which could be suspended at a point in space where the gravity was low, and that the vessel would travel around the earth like a satellite. Rosenberg also advised David that he had a way of communicating with the Russians by putting material or messages in the alcove of a theater and that he had received from one of his contacts the mathematics relating to atomic energy for airplanes.

Julius and Ethel Rosenberg, on trial for espionage, ride with Morton Sobell (far left), a member of their spy ring, in 1951.

Greenglass testified that Rosenberg claimed to have received a citation and a watch from the Russians. Greenglass also testified that Rosenberg claimed to have received a console table from the Russians which he used for photographic purposes.

In February 1950, a few days after the news of the arrest of Dr. Fuchs in England was published, Julius came to David’s home and asked David to go for a walk. During this walk Rosenberg spoke of Fuchs and mentioned that the man who had come to see David in Albuquerque was also a contact of Fuchs. Julius stated that David would have to leave the country. When David answered that he needed money, Rosenberg said that he would get the money from the Russians.

In April 1950, Rosenberg again told David he would have to leave the country, and about May 23, 1950, Rosenberg came to the Greenglass apartment with a newspaper containing a picture of Harry Gold and the story of Gold’s arrest. Rosenberg said, “This is the man who saw you in Albuquerque.” Julius gave David $1,000, and said he would come back later with $6,000 more for him to use in leaving the country and that Greenglass would have to get a Mexican tourist card. Rosenberg said that he went to see a doctor who told him that a doctor’s letter stating David was inoculated for smallpox would also be needed, as well as passport photos. He then gave Greenglass a form letter and instructions to memorize for use in Mexico City.

Upon David’s arrival in Mexico City, he was to send the letter to the Soviet Embassy and sign it “I. Jackson.” Three days later after he sent this letter, David, carrying in his hand a guide to the city with his middle finger between the pages of the guide, was to go to the Plaz De La Colon at 5 p.m. and look at the statue of Columbus there. He would wait until a man came up to him, when David would say, “That is a magnificent statue,” and tell the man that David was from Oklahoma. The man would then answer, “Oh, there are much more beautiful statues in Paris,” and would give Greenglass a passport and additional money. David was to go to Vera Cruz and then go to Sweden or Switzerland. If he went to Sweden, he was to send the same type of letter to the Soviet Ambassador or his secretary and sign the letter “I. Jackson.” Three days later, David was to go to the Statue of Linnaeus in Stockholm at 5 p.m. where a man would approach him. Greenglass would mention that the statue was beautiful and the man would answer, “There are much more beautiful ones in Paris.” The man would then give David the means of transportation to Czechoslovakia, where upon arrival he was to write to the Soviet Ambassador advising him of his presence.

Julius further advised Greenglass that he himself would have to leave the country because he had known Jacob Golos (a member of the communist underground), and that Elizabeth Bentley (also a Communist Party member).

Sometime later, David and his family went to a photography shop and had six sets of passport photos taken. On Memorial Day, Greenglass gave Rosenberg five sets of these photos. Later Rosenberg again visited David, to who he gave $4,000 in $10- and $20-bills wrapped in brown paper, requesting Greenglass to go for a walk with him and repeat the memorized instructions. David gave the $4,000 to his brother-in-law for safekeeping.

On cross-examination, David testified he used the $1,000 he received from Julius to pay household debts and the $4,000 to pay his lawyer for representing him.

Ruth Greenglass also testified at the trial, and, in addition to corroborating her husband’s testimony, gave the following information:

She stated that prior to her departure for New Mexico in November 1944, she had a conversation with Julius and Ethel Rosenberg at the Rosenberg apartment in New York City. Julius told her that he and Ethel had discontinued their open affiliation with the Communist Party because he had always wanted to do more than just be a Communist Party member. After two years, Julius had succeeded in reaching the Russians and was now doing the work he wanted to do. He requested her to enlist David’s help furnishing information to him for the Russians about Los Alamos. Ruth declined at first, but Ethel urged her to approach David. Julius then gave her instructions for David as to the particular type of information he wanted. A few days later, he gave Ruth $150 to defray the expenses of her trip to New Mexico.

On her return to New York in December 1944, after visiting David, Rosenberg visited her apartment, at which time she informed him of David’s decision to cooperate. She furnished Julius oral and written information that David gave her and informed him of David’s impending furlough. Prior to her departure for Albuquerque in February of 1945, Julius visited her and gave Ruth instructions concerning a meeting with an espionage contact in Albuquerque.

Gold Testifies

Harry Gold testified that he was engaged in Soviet espionage from 1935 up to the time of his arrest in May 1950 and that from 1944 to 1946 his espionage superior was a Russian, known to him as “John.” He identified a picture of Anatoli A. Yakovlev, former Soviet Vice-Consul in New York City, as “John.” Yakovlev’s picture was admitted into evidence.

In June 1944, Gold had an espionage meeting with Dr. Klaus Fuchs in Woodside, Queens, New York. As a result of this meeting, Gold wrote a report and turned it over to Yakovlev about a week or so later, when he told Yakovlev that at Gold’s next meeting with Fuchs, the latter would give Gold information relating to the application of nuclear fission to the production of military weapons.

In the latter part of 1944, Gold met Fuchs in the vicinity of Borough Hall, Brooklyn and received a package from Fuchs which Gold later turned over to Yakovlev.

Gold’s next meeting with Fuchs was in July 1944, in the vicinity of 9th Street and Central Park West, New York City. About a week or two later, Gold gave Yakovlev a report he had written concerning this conversation and told Yakovlev that Fuchs had given further information concerning the work of a joint American and British project to produce an atom bomb.

Subsequently, Gold had a regularly scheduled series of meetings with Yakovlev, who instructed Gold how to continue his contacts with Fuchs. Gold stated that this was to obtain information from a number of American espionage sources and give it to Yakovlev. He pointed out he organized his meetings with these sources by using recognition signals, such as an object or a piece of paper and a code phrase in the form of a greeting, always using a pseudonym. He also stated that his sources lived in cities other than Philadelphia (Gold’s home city) and that he paid money to these sources which he had in turn received from Yakovlev.

Early in January 1945, Gold met Fuchs in Cambridge, Massachusetts and received a package of papers which he later turned over to Yakovlev in New York City. He told Yakovlev that Fuchs had mentioned that a lens was being worked on in connection with the atom bomb. His next meeting with Fuchs was to be in Santa Fe on the first Saturday of June 1945.

Harry Gold

In February 1945, Gold met Yakovlev on 23rd Street between 9th and 10th Avenues in New York City. At this meeting, Yakovlev indicated the Russians’ interest in the plans mentioned by Fuchs.

On the last Saturday in May of 1945, Gold met Yakovlev inside a restaurant on 3rd Avenue in New York City, to discuss Gold’s next meeting with Fuchs in Santa Fe. Yakovlev instructed Gold to take on an additional mission in Albuquerque, New Mexico. Gold protested, but Yakovlev said it was vital, pointing out that a woman was supposed to go but was unable to make the trip. Yakovlev gave Gold an onionskin paper, on which was typed the name “Greenglass,” an address on High Street, Albuquerque and the recognition signal, “I am from Julius.” Yakovlev also gave Gold a piece of cardboard cut from a food package. He stated that Greenglass in Albuquerque would have the matching piece and that if Greenglass was not in, Greenglass’s wife would give Gold the information. Yakovlev then gave Gold $500 in an envelope to turn over to Greenglass and instructed Gold to follow an indirect route to Santa Fe and Albuquerque in order to minimize the danger of surveillance.

Gold arrived in Santa Fe on Saturday, June 2, 1945 and met Fuchs, who gave him a package of papers. Gold left Santa Fe in the afternoon on June 2 by bus and arrived in Albuquerque that evening. He went to the High Street address, found that Greenglass and his wife were not in, and stayed at a rooming house overnight. The next day he went to the High Street address and David Greenglass opened the door. Gold said, “Mr. Greenglass.” David answered, “Yes.” Gold then said, “I come from Julius,” and showed Greenglass the piece of cardboard which Yakovlev had given him. Greenglass requested Gold to come into his apartment, then took a piece of cardboard from a woman’s handbag and compared it with the piece Gold had given him. The pieces matched. Gold introduced himself to the Greenglasses as “Dave from Pittsburgh.”

Greenglass told Gold that the visit was a surprise and that it would take several hours to prepare the A-bomb material. He started to tell Gold about possible recruits at Los Alamos, but Gold cut him short and pointed out to David that it was very hazardous and that David should be circumspect in his behavior. Gold left and returned later that afternoon, when David gave him an envelope which he said contained information on the atom bomb. Gold turned over to David the envelope containing the $500. Greenglass mentioned to Gold that he expected to get a furlough sometime around Christmas and gave Gold Julius’s phone number in New York City in the event that Gold wanted to reach Greenglass.

Gold returned to New York City by train on June 5, 1945. While en route, he examined the material David had given him and put it in a manila envelope. He put the material he had received from Fuchs into a different manila envelope. That evening Gold met Yakovlev along Metropolitan Avenue in Brooklyn and gave him both envelopes.

About two weeks later Gold met Yakovlev on Main Street in Flushing, New York. Yakovlev told Gold that the information he had received from him on June 5 had been sent immediately to the Soviet Union and that the information he had received from Greenglass “was extremely excellent and valuable.” At this meeting, Gold related the details of his conversation with Fuchs and Greenglass. Fuchs had stated that tremendous progress had been made on the atom bomb and that the first explosion had been set for July 1945.

In early July 1945, Gold met Yakovlev in a seafood restaurant. Yakovlev said it was necessary to make arrangements for another Soviet agent to get in touch with Gold. At Yakovlev’s instructions, Gold took a sheet of paper from his pocket which had the heading of a company of Philadelphia. Gold tore off the top portion containing the name and on the reverse side of the sheet wrote in diagonal fashion, “Directions to Paul Street.” Yakovlev then tore the paper in an irregular fashion. He kept one portion and Gold kept the other. Yakovlev said that if Gold received two tickets in the mail without a letter, it would mean that on a definite number of days after the date on the ticket Gold was to go to the roadway stop of the Astoria Line for a meeting which would take place in a restaurant-bar. Gold’s Soviet contact would be standing at the bar and approach Gold, asking to be directed to Paul Street. They would then match the torn pieces of paper.

In August 1945, Gold again met Yakovlev in Brooklyn and was told to take a trip in September 1945 to see Fuchs. Gold suggested to Yakovlev that since he was going to see Fuchs, he might as well go to Albuquerque to see David Greenglass. Yakovlev answered that it was inadvisable because it might endanger Gold to have further contact with Greenglass.

In September 1945, Gold met Fuchs in Santa Fe, New Mexico. On his return to New York City on September 22, 1945, Gold went to a prearranged meeting place to see Yakovlev, who failed to appear. About ten days later, Gold met Yakovlev at Main Street, Flushing, and turned over to him a package he had received from Fuchs. He told Yakovlev that Fuchs has said there was no longer the open and free cooperation between the Americans and the British and that many departments were closed to Fuchs. Fuchs also stated that he would have to return to England and that he was worried because the British had gotten to Kiel, Germany, ahead of the Russians and might discover a Gestapo dossier there on Fuchs which would reveal his strong Communist ties and background. Fuchs and Gold also discussed the details of a plan whereby Fuchs could be contacted in England.

In November 1945, Gold had another meeting with Yakovlev at which time Gold mentioned that Greenglass would probably be coming home around Christmas for a furlough. Gold said plans should be made to get in touch with Rosenberg in an effort to obtain more information from Greenglass.

In January 1946, Gold again met with Yakovlev and was told about a man Yakovlev had tried to contact who was under continuous surveillance. Yakovlev used this story to illustrate that it was better to give up the contact than endanger their work.

Early in December 1946, Gold received two tickets to a boxing match in New York City through the mail. The tickets were addressed to Gold’s Philadelphia home incorrectly and too late for Gold to keep the appointment. At 5 p.m. on December 26, 1946, Gold received a telephone call at his place of employment. The voice said, “This is John.” Gold then arranged with John to meet an unidentified man in a certain movie theater that night. The man identified himself by handing Gold the torn piece of paper containing the heading which Gold and Yakovlev had previously prepared. This man asked Gold to proceed to 42nd Street and 3rd Avenue, New York City, to meet Yakovlev.

He met Yakovlev, who asked if Gold had anything further from Fuchs, apologized for his 10 months’ absence and explained that he had to lie low. He stated that he was glad Gold was working in New York and told Gold he should begin to plan for a mission to Paris, France in March 1947, where Gold would meet a physicist. He gave Gold an onionskin paper setting forth information for his proposed meeting in Paris. During the conversation with Yakovlev, Gold mentioned the name of his employer, and, upon hearing this, Yakovlev became very excited. He told Gold that Gold had almost ruined 11 years of work by working for this individual because he had been investigated in 1945. Yakovlev dashed away, stating that Gold would not see him in the United States again.

It is interesting to note that the Soviet intelligence services, in utilizing Gold to contact Greenglass, made a mistake in security that ultimately led to the uncovering of the Rosenberg spy ring, a network independent of the one Gold was involved in. From FBI knowledge of Soviet intelligence activities, it is known that the Soviets with their stress on security will not usually allow a member of one network to know of the existence of another network so that in the event one network is detected, the other will not be compromised. It will be recalled that Gold’s protest to Yakovlev about contacting Greenglass in Albuquerque went unheeded. The Soviets undoubtedly found good reason to regret this error in judgment.

A nuclear chemist testified that from 1944 to 1947 he was associated with the atom bomb project at Los Alamos. He stated that his own work was related to implosion research and classified secret. He further stated that he would go to the machine shop, furnish sketches to the supervisor of the shop and determine what was needed. The nuclear chemist recalled seeing David Greenglass in the machine shop. He identified the sketches prepared by David Greenglass at the trial and entered as exhibits reasonably accurate replicas of the type of sketches he, himself, submitted to the machine shop. These specimens could have been of value to a foreign power, the nuclear chemist stated, and would reveal to any expert what was going on at Los Alamos and indicate to the expert its relation to the atom bomb.

Elitcher Testifies

Max Elitcher testified that he first met Sobell while both were attending a high school in New York City. He further stated that he and Sobell also attended college together in New York from 1934 to 1938. Elitcher graduated with a bachelor’s degree in electrical engineering and pointed out that Julius Rosenberg also studied engineering at the same college during this same period. Elitcher saw Sobell daily at school but saw Rosenberg less frequently. After graduating, Elitcher was employed with the Bureau of Ordnance, Navy Department, Washington, D.C., from November 1938 until October 1948.

Max Elitcher. Library of Congress photograph.

In December 1938, Elitcher resided in Washington, D.C. During December of that year Sobell came to Washington and stayed at a house next to Elitcher’s place of residence. In April or May 1939, Elitcher and Sobell took up residence in a private home, and in May of 1940, they moved into an apartment. During the period they lived together Sobell was also employed at the Bureau of Ordnance. In September 1941, Sobell left his employment to go to a university in Michigan in order to continue his studies.

Elitcher further advised that during the period he lived with Sobell they had conversations concerning the Communist Party and that, at Sobell’s request, Elitcher joined the Young Communist League. About September 1939, Elitcher attended a meeting with Sobell at which there was a discussion about forming a branch of the Communist Party. This branch was formed and Elitcher joined the Communist Party at the end of 1939. Meetings of this group were held at the homes of various members and dues were paid to the chairman of the group. Elitcher stated that Sobell was the first chairman of the group.

At meetings, discussions were conducted of news events based on the The Daily Worker and literature such as The Communist. The group also discussed Marxist and Leninist theory. Suggestions were made to the members to join the American Peace Mobilization and to assist the American Youth Congress convention. Discussions were also held concerning the Hitler-Stalin Pact, and members were instructed to strive to get support of other people for the Russian position. Elitcher continued to go to these meetings until September 1941. In 1942, Communist Party branches were formed which contained groups of employees from particular government agencies, and Elitcher joined the Navy branch of the Communist Party.

Elitcher testified that around June 1944, he received a telephone call from Julius Rosenberg who identified himself as a former college classmate of Elitcher. At Elitcher’s invitation Rosenberg visited the Elitcher home the same evening. Rosenberg told Elitcher what the Soviet Union was doing in the war effort and stated that some war information was being denied that country. Rosenberg pointed out, however, that some people were providing military information to assist the Soviet Union. Rosenberg asked Elitcher to supply him with plans, reports, or books regarding new military equipment and anything Elitcher thought would be of value to the Soviet Union, pointing out that the final choice for the Soviet Union of the value of the information would not be up to Elitcher, but that the information would be evaluated by someone else.

In September 1944, Elitcher went on a one-week vacation in a state park in West Virginia with Morton Sobell and his future wife. During this vacation, Elitcher told Sobell about Rosenberg’s visit and request for information to be given to the Soviet Union. When he remarked that Rosenberg had said Sobell was helping in this, Sobell became angry and said that Rosenberg should not have mentioned his name.

In the summer of 1945, Elitcher was in New York on vacation and stayed at the apartment of Julius Rosenberg. Rosenberg mentioned to Elitcher that Rosenberg had been dismissed from his employment for security reasons and that his membership in the Communist Party seemed to be the basis of the case against him. Rosenberg had been worried about this matter because he thought his dismissal might have had some connection to his espionage activity, but he was relieved when he found out it concerned only his communist activity.

Elitcher also testified that in September 1945, Rosenberg came to Elitcher’s home and told him that even though the war was over, Russia’s need for military information continued. Rosenberg asked Elitcher about the type of work he was doing, and Elitcher told him he was working on sonar and anti-submarine fire-control devices.

In the early part of 1946, Elitcher visited an electric company in connection with official business and stayed at the home of Sobell in Schenectady. At the time, Sobell was working at this electric company. On this occasion Sobell and Elitcher discussed their work.

Later that year Elitcher again saw Sobell, and Sobell asked about an ordnance pamphlet, but Elitcher said it was not yet ready. Sobell suggested that Elitcher see Rosenberg again.

At the end of 1946 or in 1947, Elitcher telephoned Rosenberg and said he would like to see him. At this time Rosenberg advised Elitcher that there had been some changes in the espionage work, that he felt there was a leak, and that Elitcher should not come to see him until further notice. He also advised Elitcher to discontinue his communist activities.

Elitcher testified that in 1947, Sobell had secured employment at an instrument company in New York City doing classified work for the Armed Forces. Elitcher saw Sobell there several times and on one occasion had lunch with him at a restaurant in New York City. Sobell asked Elitcher on this occasion if he knew of any progressive students or graduates and if so, whether he would put Sobell in touch with them. Elitcher said he did not know any.

In October 1948, Elitcher left the Bureau of Ordnance and went to work for the instrument company in New York City where Sobell was employed. He lived in a house in Flushing, New York, and Sobell lived on a street behind him. They went to work together in a car pool. During a trip home from work one evening, Sobell again asked Elitcher about individuals Elitcher might know who would be progressive. Sobell pointed out to Elitcher that because of security measures being taken by the government, it was necessary to find students to provide information whom no one would suspect.

Elitcher further testified that prior to leaving the Bureau of Ordnance, he had discussed with Sobell his desire to secure new employment during a visit Elitcher made to New York City in the summer of 1948. Sobell told Elitcher not to leave the Bureau of Ordnance until Elitcher had talked to Rosenberg.

Thereafter, Sobell made an appointment for Elitcher to meet with Rosenberg. They met on the street in New York, and Rosenberg told Elitcher that it was too bad Elitcher had decided to leave because Rosenberg needed someone to work at the Bureau of Ordnance for espionage purposes. Sobell was present at this meeting and urged Elitcher to stay at the Bureau of Ordnance. Rosenberg and Elitcher then had dinner together at a restaurant in New York City where they continued to talk about Elitcher’s desire to leave his job. Rosenberg wanted to know where important defense work was being done, and Elitcher mentioned laboratories at Whippany, New Jersey. Rosenberg suggested that possibly Elitcher could take courses at college to improve his status.

Elitcher also testified that in July 1948, he took a trip to New York City by car during which he believed he was being followed. He proceeded to Sobell’s home and told him of his suspicion. Later that evening, Sobell mentioned to Elitcher that he had some information for Rosenberg which was too valuable to destroy, and he wanted to get it to Rosenberg that night. He requested Elitcher to accompany him.

Elitcher observed Sobell take a 35-millimeter film container with him and place it in the glove compartment of Sobell’s car. Sobell and he then drove to a building in New York City and parked on Catherine Street. Sobell took the container out of the glove compartment and left. When he returned, Elitcher asked him what Rosenberg thought of Elitcher’s suspicion that he was being followed, and Sobell answered that Rosenberg thought it was nothing to worry about.

Elitcher testified that Sobell possessed a camera, some 35-mm film and an enlarger, and that all of the material Sobell worked on in his various places of employment was classified. He stated he last saw Sobell in June 1950.

On cross-examination, Elitcher recalled that during Rosenberg’s visit to his house in June 1944, which was after D-Day, Rosenberg mentioned that he had a drink with a Russian in celebration of this event. Elitcher testified that Rosenberg contacted him at least nine times from 1944 to 1948 in an attempt to persuade him to obtain information for him, but that he always put Rosenberg off. In 1948, Elitcher told Rosenberg that he definitely would not cooperate with him.

Bentley Testifies

Elizabeth Bentley, a confessed former Communist, testified that she was a member of the Harlem section of the Communist Party from 1935 to 1938. In July 1938, she secured a job in the Italian Library of Information and for the remainder of that year was instructed to go underground and to pretend not to know other communists.

While employed there, she came to know Feruccio Marini, a Communist Party official who handled Italian Communist activity in the United States. She knew Marini under the name of F. Brown. In October 1938, she met Jacob Golos through Marini. Golos was in the communist underground and operated World Tourist, Inc., a travel agency set up in 1927 by the Communist Party. Until his death in November 1943, Golos had been a member of the three-man control commission of the Communist Party in the United States.

According to Bentley, the Communist Party of the United States was part of Communist International. After Golos died, Bentley had other contacts, the last one being Anatole Gromov, First Secretary of the Soviet Embassy in the United States; her final contact with Gromov being in December 1945. She stated that the information which Golos had obtained was passed on to the Soviet Embassy.

After Golos died, Bentley’s duties consisted of collecting information from communists employed in the U.S. government and passing it on through communist superiors to Moscow. She stated that the Communist Party in the United States served the interests of Moscow. She revealed that she transmitted orders to Earl Browder from Moscow which he had to accept. Pointing out the close relationship between the Communist Party in this country and Communist International, Bentley stated that this close relationship was preached at Communist Party meetings. Any member who did not adhere to the Party line, as dictated by Communist International in Moscow, was expelled. She revealed that all of her contacts in her work were obtained from the Communist Party.

In the summer of 1945, Bentley reported to the FBI all her activities and was asked if she would continue her activities under FBI guidance, which she did until the spring of 1947.

Elizabeth Bentley. Library of Congress photograph.

Bentley stated that, during her association with Golos, she became aware of the fact that Golos knew an engineer, named “Julius.” In the fall of 1942, she accompanied Golos to Knickerbocker Village but remained in his automobile. She saw Golos conferring with Julius on the street but at some distance. From conversations with Golos, she learned that Julius lived in Knickerbocker Village. She also stated that she had telephone conversations with Julius from the fall of 1942 until November 1943.

In interviews with FBI agents, Bentley had described Julius as being about 5’10”, slim, and wearing glasses. She had also advised that he was the leader of a Communist cell of engineers which was turned over to Golos for Soviet espionage purposes. Julius was to be the contact between Golos and the group. Golos believed this cell of engineers was capable of development.

Investigation by the FBI disclosed that Julius Rosenberg resided in a development known as Knickerbocker Village, was 5’10” tall, slim, and wore glasses. Bentley, however, was unable to make a positive identification of Julius.

Verdicts Reached

Julius and Ethel Rosenberg testified and denied all espionage allegations against them. They admitted having a console table, but denied it was a gift from the Russians, as claimed by David Greenglass and his wife. They stated that they bought the table at a New York City department store in 1944 or 1945. On cross-examination, they were asked questions as to their communist affiliations but refused to answer on the grounds of self-incrimination.

On March 28, 1951, counsel for each side summed up their respective case to the jury. On March 29, 1951, the jury rendered a verdict of guilty against the three defendants, Julius and Ethel Rosenberg, and Morton Sobell.

On April 5, 1951, the following sentences were imposed: Julius Rosenberg, death, such sentence to be carried out during the week of May 21, 1951; Ethel Rosenberg, death, such sentence to be carried out during the week of May 21, 1951; and Morton Sobell, imprisonment for a term of 30 years.

Communist Party Front Activities and Propaganda on Behalf of the Rosenbergs

The desperate legal struggle waged on behalf of the Rosenbergs was matched in intensity by an extraordinary propaganda drive to “Save the Rosenbergs.” Significantly, the communists’ frenzied effort to rescue the Rosenbergs from what they termed “legal murder” was deferred for more than a year after their arrests and for more than four months after they had been found guilty in a trial which the communists later called a “monstrous frame-up” and “a travesty of justice.”

At first the Rosenberg trial went completely unnoticed in the usually vigilant Communist Party press. Not a word about the alleged Rosenberg “frame-up” appeared in the The Daily Worker until the day after the jury returned a verdict of guilty. Moreover, the Party’s first public recognition of the Rosenberg case gave no hint whatever of the tremendous propaganda storm that the communists would later raise over the Rosenbergs. Buried inconspicuously on page 9 of the March 30, 1951, The Daily Worker, the Rosenberg conviction was reported in routine fashion.

No further notice appeared in the The Daily Worker concerning the Rosenberg case until April 6, 1951, when it was announced under a feature headline as follows: “Rosenbergs Sentenced to Death, Made Scapegoats for Korean War.” The article, noting that the Rosenbergs were parents of two small children, appeared to be aimed chiefly at condemning the severity of the sentence, rather than the verdict itself. The word “frame-up,” later to become virtually synonymous with the Rosenberg trial in communist propaganda, was not yet used. In the same issue of the The Daily Worker, a front-page editorial charging that American “panic mongers” were deliberately trying to create an atmosphere of war made several oblique references to the Rosenberg case without, however, directly questioning the verdict.

It was not until midsummer of 1951 that the propaganda campaign on behalf of the Rosenbergs began in earnest. Even at this late date, the Communist Party did not immediately commit itself to the task of vindicating the Rosenbergs and exposing the “hideous plot” against them. Instead, the campaign was initiated in the form of a series of articles in the National Guardian. This publication was described in 1949 by the California Committee on Un-American Activities as notoriously Stalinist in its staff, writers, management, and content.

It is evident that the clemency drive on behalf of the Rosenbergs was from the beginning a highly artificial affair and was carefully promoted rather than a spontaneous public reaction which the communist press sought to show. This was indicated from the mere fact that the The Daily Worker was about to print the names and addresses of hundreds of clergymen and intellectuals who had written to the President asking for clemency. Unless the National Committee to Secure Justice in the Rosenberg Case (NCSJRC), or the Communist Party, had solicited such letters themselves, the Party press would have had no way of knowing who had written to the White House except in a few isolated incidents. At a number of rallies sponsored by the NCSJRC, individuals in attendance were handed telegrams, post cards, or letters which were completely filled out and addressed to the president and which lacked only a signature. In addition, it was reported that representatives of the NCSJRC conducted intensive house-to-house canvasses in an effort to obtain signatures for clemency petitions.

From December 27, 1952 to January 17, 1953, a continuous round-the-clock picket line was maintained by Rosenberg sympathizers at the White House during the period that former President Truman was presumably studying a plea for executive clemency. This “White House Clemency Vigil” was called off on January 17, 1953, after more than 500 consecutive hours, only when it became evident that President Truman would not rule on the petition for clemency prior to his retirement from office. According to the The Daily Worker, this affair climaxed on January 5, 1953, when more than 2,000 persons from 22 states arrived at the District of Columbia to take part in the “vigil.”

As the final legal moves were being made by the Rosenbergs’ defense attorneys, thousands of pickets formed around the White House in June 1953. The majority of these pickets poured into Washington, D.C. from New York City, where the NCSJRC had arranged for several special “clemency trains” to carry these Rosenberg sympathizers to the Nation’s capital.

The picketing at the White House began at approximately 1:30 p.m. on June 14; at 4:00 p.m. the pickets marched to Ninth Street and Constitution Avenue, Northwest, where the NCSJRC held a “prayer meeting” at which the Rosenbergs were eulogized by officials of the Committee and several clergymen.

An official count of the pickets by the Washington, D.C., Metropolitan Police Department indicated that there were approximately 6,800 persons involved in this attempt to pressure the President of the United States into granting clemency for the convicted atom spies. The NCSJRC’s own estimate of the number of pickets was set at 13,000.

Following this “prayer meeting,” the majority of pickets returned to New York City, leaving a small handful of pickets to continue the “24-hour vigil” at the White House. The picketing of the White House continued until June 17, 1953, when after the U.S. Supreme Court recessed for the summer, one of the Supreme Court justices announced that he had granted a stay of execution in order that new points of law brought before him by defense attorneys could be heard by the lower courts.

Upon receiving the news that the government was successful in petitioning for an extraordinary session of the U.S. Supreme Court, the NCSJRC went into action and again sent pickets to parade before the White House. The picketing continued until the execution of the Rosenbergs was announced at approximately 8:45 p.m. on June 19, 1953, at which time about 500 pickets were on hand at the White House.

This case has been used by Communist Parties throughout the world for propaganda purposes against the United States. American embassies in Canada and Europe were flooded with petitions for clemency by various people and organizations. During the last few days prior to the execution of the Rosenbergs, demonstrations were held in major capitals of Europe, such as Paris, Rome, and London. In a news release on June 20, 1953, foreign reaction to the execution was reported as follows: “ ‘Paris - Communist-led groups swarmed through European streets last night and early today in generally orderly demonstrations protesting the execution of atom spies Julius and Ethel Rosenberg. A French teenager was shot and wounded and 386 persons were arrested in Paris.”

On February 11, 1953, President Dwight D. Eisenhower denied the petition for executive clemency filed by the Rosenbergs. In denying this petition, President Eisenhower stated, “These two individuals have been tried and convicted of a most serious crime against the people of the United States. They have been found guilty of conspiring with intent and reason to believe that it would be to the advantage of a foreign power, to deliver to the agents of that foreign power certain highly secret atomic information relating to the national defense of the United States. The nature of the crime for which they have been found guilty and sentenced far exceeds that of the taking of the life of another citizen; it involves the deliberate betrayal of the entire nation and could very well result in the death of many, many thousands of innocent citizens. By their act these two individuals have, in fact, betrayed the cause of freedom for which free men are fighting and dying at this very hour.”

President Eisenhower continued, “The courts have provided every opportunity for the submission of evidence bearing on this case. In this time-honored tradition of American justice, a freely selected jury of their fellow citizens considered the evidence in this case and rendered its judgement. All rights of appeal were exercised and the conviction of the trial court was upheld after full judicial review, including that of the highest court in the land. I have made a careful examination into this case, and I am satisfied that the two individuals have been accorded their full measure of justice. There has been neither new evidence nor have there been mitigating circumstances which would justify altering this decision and I have determined that it is my duty, in the interest of the people of the United States, not to set aside the verdict of their representatives.

On May 29, 1953, the district judge set the date of execution of the Rosenbergs for the week of June 15, 1953. At the time, the usual execution date at Sing Sing Prison was Thursday night, which meant the Rosenbergs were scheduled to die on June 18, 1953.

Still, additional appeals both to the Circuit Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit and the U.S. Supreme Court followed.

Finally, on June 16, 1953, a Justice of the U.S. Supreme Court requested the Rosenberg defense attorneys to submit their petitions for a stay of execution in writing. On that date, two attorneys appeared at the Supreme Court and attempted to file petitions for a writ of habeas corpus on behalf of the Rosenbergs. Their action in attempting to file these writs was opposed by attorneys for the Rosenbergs. These petitions for a writ of habeas corpus were heard by the Supreme Court Justice in his chambers.

The main issue made in the petition was that, under the 1946 Atomic Energy Act, the death sentence might be imposed only upon the recommendation of the jury and then only when the defendants were charged with intent to injure the United States. It was argued that, inasmuch as the conspiracy for which the Rosenbergs were convicted commenced in 1944 and existed until 1950, the provisions of the Atomic Energy Act applied to the sentencing, rather than the provisions of the Espionage Act of 1917.

On June 17, 1953, a stay of execution was granted by this Justice in order that the question raised could be argued in the District Court and more evidence received in order to determine whether there was merit to the argument.

On June 19, 1953, a special session of the U.S. Supreme Court, which had been called by the Chief Justice, vacated the stay of execution granted two days previously.

On June 19, 1953, the President of the United States refused to grant executive clemency to Julius and Ethel Rosenberg. In this refusal, the President stated, “Since its original review proceedings in the Rosenberg case by the Supreme Court of the United States, the courts have considered numerous further proceedings challenging the Rosenberg convictions and the sentences imposed. Within the last two days, the Supreme Court, convened in a special session, has again reviewed a further point which one of the justices felt the Rosenbergs should have an opportunity to present. This morning the Supreme Court ruled that there was no substance to this point. I am convinced that the only conclusion to be drawn from a history of this case is that the Rosenbergs have received the benefit of every safeguard which American justice can provide. There is no question in my mind that their original trial and the long series of appeals constitute the fullest measure of justice and due process of law. Throughout the innumerable complications and technicalities of this case, no judge has ever expressed any doubt that they committed most serious acts of espionage. Accordingly, only most extraordinary circumstances would warrant executive intervention in this case. I am not unmindful of the fact that this case has aroused grave concern both here and abroad. In this connection, I can only say that by immeasurably increasing the chances of atomic war the Rosenbergs may have condemned to death tens of millions of innocent people all over the world. The execution of two human beings is a grave matter, but even graver is the thought of the millions of dead whose death may be directly attributable to what these spies have done.”

The President continued, “When democracy’s enemies have been judged guilty of a crime as horrible as that of which the Rosenbergs were convicted; when the legal processes of democracy have been marshaled to their maximum strength to protect the lives of convicted spies; when in their most solemn judgment the tribunals of the United States have adjudged them guilty and the sentence just, I will not intervene in this matter.”

At 8:05 p.m. on June 19, 1953, Julius Rosenberg was executed at Sing Sing Prison, Ossining, New York. At 8:15 p.m. on the same date, Ethel Rosenberg was executed at Sing Sing Prison.

David Greenglass, who received a 15-year sentence after a guilty plea, was released from Federal prison on November 16, 1960. He was required to report periodically to a parole officer until November 1965.