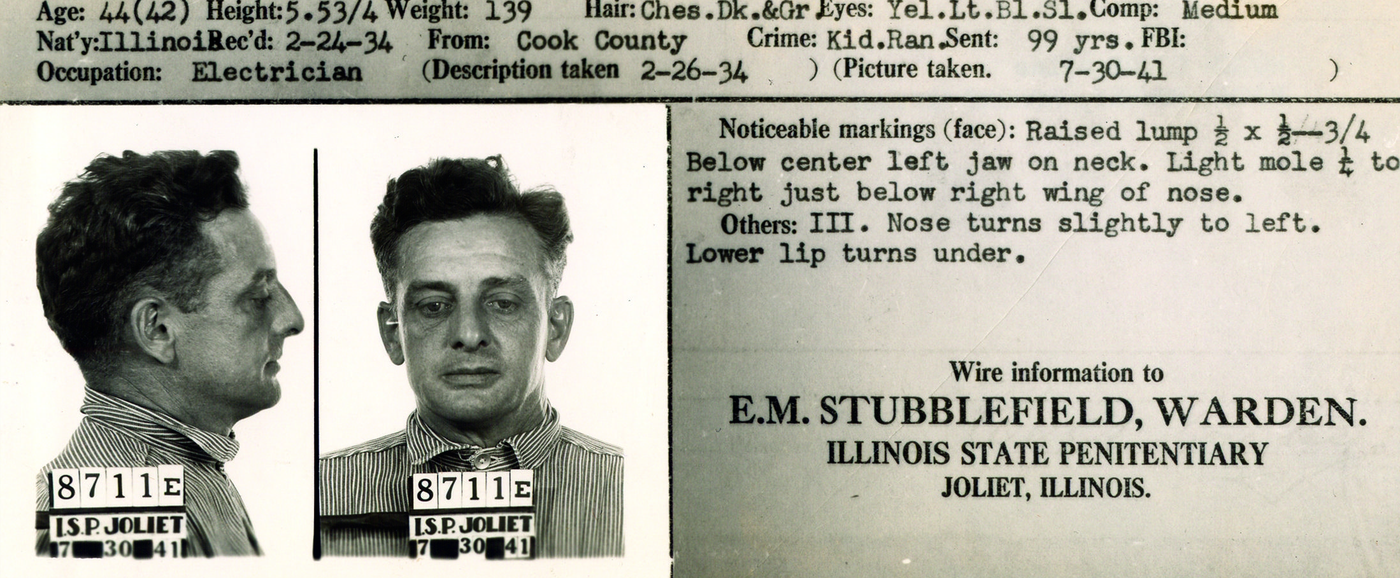

Roger “The Terrible” Touhy

Mug shot and partial criminal record of Roger “The Terrible” Touhy. Touhy and his gang of violent criminals escaped from a penitentiary in Illinois in October 1942.

After the FBI disbanded a dangerous group of criminals in 1934, a prison break in 1942 put Roger Touhy and several of his confederates back on the run.

Here’s how the FBI put the gang out of business for good.

Touhy Goes to Prison

In the latter part of 1933 and the early part of 1934, the Chicago gang of Roger “The Terrible” Touhy was smashed.

Singly and in groups, the Touhy mobsters were accounted for. James Tribble was murdered on September 8, 1933 in Chicago. William Sharkey committed suicide at St. Paul on December 1, 1933. Touhy himself and two of his henchmen were convicted in state court at Chicago on February 23, 1934, and sentenced to serve 99 years in prison for kidnapping John “Jake the Barber” Factor and holding him for ransom. The FBI had investigated the Factor kidnapping, but had stepped out at the conclusion of the investigation and turned over all evidence to state authorities. The federal courts had no jurisdiction because the kidnappers had not taken their victim across a state line.

Charles C. Connors was murdered at Willow Springs, Illinois, on March 13, 1934. On the same date, Basil “The Owl” Banghart, machine gunner and aviator for the mob, was convicted in state court in Chicago and sentenced to serve 99 years for participating in the Factor kidnapping. Two months later, Banghart was also tried in federal court at Asheville, North Carolina, and sentenced to serve 36 years in prison on a charge of robbing United States mail.

Two remaining members of the Touhy gang, Isaac A. Costner and Ludwig Schmidt, were also convicted on the mail robbery charge.

By the end of May 1934, three members of the mob were dead, and 11 were in prison serving long terms.

The Escape Plan

For half a decade, the northwest section of Cook County, Illinois, had been known as Touhy Territory and the infamous mob had made bizarre history throughout the Midwest and along the Atlantic seaboard under the leadership of Roger Touhy, one of six notorious sons of James Touhy, deceased, a former patrolman in the Chicago Police Department.

Touhy “The Terrible” was quickly forgotten after he was received in Stateville Penitentiary at Joliet in 1934. Banghart started serving his long term in the Illinois State Prison at Menard. After a break from Menard in 1935, however, he was transferred to Joliet, where he renewed acquaintance with Touhy.

For seven years, Touhy and Banghart remained in prison, keeping in touch with their old outside contacts through the fantastic medium of the underworld grapevine, watching for any possible chance of escape.

They took no one into their confidence. Banghart already had four previous escapes on his record, and when he went to Joliet, he boasted that no prison in the world could keep him. He observed the activities of prison guards and assimilated every item of information that might be important in a planned escape. He learned the exact location of all prison facilities; the height of the walls; the position of the prison towers and the distance between them; and the number of guards and the kind of weapons they carried. He even claimed to know that the guards carried rifles sighted in at 100 yards, although they manned towers which were 300 yards apart.

Ultimately, a plan of escape matured, a plan which necessitated assistance both inside and out.

First of all, Touhy and Banghart needed guns; so they took Big Ed Darlak into their confidence. Edward Darlak was a 32-year old lifer, received at Joliet on October 14, 1935, under a 199 year sentence for murder.

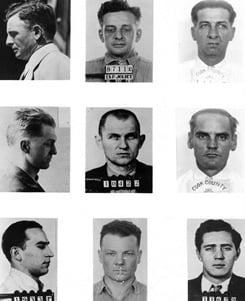

Members of the Touhy Gang who escaped prison in 1942. Top row (from left to right): Roger Touhy (first two pictures) and William Stewart. Middle row (from left to right): Basil Hugh Banghart (first two images) and Martilick Nelson. Bottom row (from left to right): Edward Darlak, Eugene Lanthorn (or James O'Connor), and St. Clair McInerney.

Darlak sent word to a young brother, Casimir, on the outside. Casimir got two .45 caliber revolvers, together with ammunition, and one night in August 1942, tossed them into bushes near the prison. The guns were smuggled into the prison by a trusty who had the duty of lowering the prison flag each evening. He carried the guns in, wrapped in the flag.

With this accomplished, Banghart started negotiations for outside assistance. He needed a getaway car and a hide-out. Tentative arrangements were made but the plans were never consummated. The shabby characters willing to provide such services for a fee were not punctual or reliable. Again, it was “The Owl” who overcame the difficulties. He observed that a prison guard who manned tower number three drove his own car to work and left it parked near the tower gate, outside the prison wall. Banghart felt he could shift for a hide-out once he reached that car, because the entire Chicago area was familiar territory.

Touhy, Banghart, and Darlak passed word to four other Joliet long-termers willing to risk a break:

- William Stewart, 43 years old, under two 20-year sentences as a habitual criminal, parole violator and highway robber;

- Eugene Lanthorn (or James O'Connor), 36 years old, under a sentence of one year to life for assault to commit murder and for two previous escapes from Joliet;

- St. Clair McInerney, 31 years old, under sentence of one year to life for robbery, burglary, and violation of parole; and,

- Martilick Nelson, 40 years old, under sentence of one year to life as a robber, habitual criminal and parole violator.

The Prison Break

Shortly before 1:00 p.m., on October 9, 1942, Touhy began the break from Joliet.

He assaulted the driver of a prison garbage truck, obtained the truck and drove to the mechanical shop where Lanthorn was working, arriving there simultaneously with Banghart, McInerney, Darlak, Stewart, and Nelson.

Working together, the seven convicts overpowered guards on duty in the shop, cut telephone wires, ripped some ladders out of locked racks, piled into the truck and headed for the northwest corner of the prison yard, holding two guards as hostages. Touhy and Banghart were brandishing .45 revolvers. Lanthorn was armed with a “Molotov Cocktail”—a crude incendiary bomb which he had fashioned in the prison shop and which he intended to use to start a panic if necessary. He did not need to use his bomb, however.

When the truck pulled up at the foot of tower number three, one of the convicts fired at the guard in the tower, bringing him under control. Others threw ladders up against the wall.

Touhy led five of the men up into the tower where they disarmed the guard and seized the keys to the tower gate and the keys to the guard’s car. Banghart stayed below to cover them and the guards who had been brought from the shop as hostages. Nelson went down the outside wall by rope, opened the tower door with the guard’s keys, and the gang ran out. They fled in the guard’s automobile taking the cinder road that would bring them out on the highway to Chicago. The convicts were well armed. From tower number three, they had taken two high-powered rifles and a .45 caliber handgun.

Hiding Out

At eight o’clock that evening, the getaway car, traveling at furious speed, broke through a police blockade at Elmhurst. At 11:00 p.m., the car was abandoned at Villa Park, in the middle of town where it could not be missed; the gang’s way of notifying the FBI that they had not taken a stolen car across a state line.

From Villa Park, they fled into the Cook County Forest Reserve on foot and hid out in a shack for four days. Banghart foraged for food at night. On the evening of October 13, he returned to the shack with a stolen automobile and moved the gang to a 13th Street apartment on the West Side.

Posing as long-distance truck-drivers, they all lived in his apartment for almost two months. Banghart was trying to hold them together long enough to plan and execute some big-time hold-ups which would bring in the fabulous sums of money needed in their schemes. They wanted to buy a farm near Chicago for a hide-out; they wanted legitimately purchased automobiles to obviate the danger of traveling in “hot” cars; and they wanted plastic surgery work done to change their appearances and destroy their fingerprints. Touhy was said to have the contacts for the plastic surgery, but the cost was $100,000.

Holding such a collection of desperate men together and keeping them in safe hiding was no easy job. Banghart ruled them with an iron hand. He allowed no drinking, except for an occasional bottle brought into the apartment, and permitted no promiscuous associations with outsiders. Every day when a man went out for food and supplies, Banghart, armed with a sawed-off shotgun wrapped in a newspaper, followed to convoy. The convicts changed clothes with each other frequently, made every effort to disguise themselves and, when on the streets, always walked facing oncoming traffic so that police or FBI cars could not slip up on them from behind.

About December, 1, 1942, the gang, feeling that neighbors had begun to notice them, moved to a nearby apartment, but bedbugs drove them out in two days. Their next residence was in the Doversun Apartments on Sunnyside Avenue.

They had been at Doversun only a few days when the first serious rift occurred; Stewart and Nelson went out alone one night and returned to the apartment drunk. Banghart disarmed them and pistol whipped them both, beating them until they were unconscious. Leaving the two battered and apparently dying, the other five convicts immediately abandoned the apartment and lived for a few days in a garage where they had their stolen car hidden.

Banghart, Darlak, Touhy, McInerney, and Lanthorn ultimately moved into the Norwood Apartments at 1256 Leland Avenue. Stewart and Nelson somehow recovered, got out of the Doversun Apartments before they were discovered, and separated—Nelson to go to Minneapolis and Stewart to seek refuge with a former girlfriend in Chicago.

The FBI Joins the Hunt

Although this crowd escaped from Joliet on October 9, 1942, the FBI did not enter the search for them until October 16, 1942. They were state prisoners, and in escaping they violated no federal law. But after a week had passed and they had failed to present themselves for registration under the Selective Service Law they became draft delinquents. The FBI formally filed on them for failure to register and obtained federal warrants of arrest.

Realizing that this gang of desperadoes constituted a grave threat to the public safety, Director J. Edgar Hoover personally took charge of the Touhy investigation at its inception. From his Washington Headquarters he directed a continent-wide man hunt that had no equal since the days of Dillinger.

Agents at FBI Headquarters dug into the old voluminous files on the Factor kidnapping for every fragment of information about Touhy and Banghart’s past associates, hide-outs, habits, friends and relatives. Agents were sent into Joliet to review prison records for the names of all relatives, visitors, and correspondents of all seven escapees. They interviewed prison guards and convicts who were known to have associated in any way with any of the seven subjects. Convicts who had formerly associated with them but who had already been discharged from prison were located. Old prison records in other institutions where the subjects had served time were examined.

Every known relative, every former friend or character witness, every attorney who was known to have represented the men—every possible contact of all seven subjects was located. Those who were cooperative were interviewed for their assistance, while others were watched night and day. Photographs, descriptions, and brief criminal histories of all the escapees were sent to every law enforcement agency in America, to all leading newspapers and to agencies in Canada and Mexico. Stops were placed along the borders and all patrol stations were given photographs of the convicts.

Every lead, no matter how shadowy, was cautiously and thoroughly run out.

In the initial stages, the investigation was primarily an exhaustive preparation of a nation-wide network of ambushes. Sooner or later a break would come—one of the fugitives would attempt a contact that was covered.

Mere waiting, however, was not enough. To conserve manpower and expenses and to bring these desperadoes into custody at the earliest possible moment, it was necessary to make deductions on which to predicate offensive action.

Director Hoover and his staff deduced that Banghart would try to hold the gang together; that they would hide out in Chicago; and that, by means of pocket picking and petty stick-ups, they would obtain identification papers such as Selective Service cards to avoid an accidental arrest for vagrancy or the like.

Agents carefully reviewed the Chicago police files on unsolved petty stick-up cases in which the victim had lost a wallet containing draft cards and other identification.

Initial Success

The first break came on December 15, 1942, when Nelson attempted to contact a relative in north Minneapolis. Knowing, therefore, that Nelson was in the area and that he was not staying with relatives, agents assumed that he was stopping at some cheap hotel using an alias. A logical alias would be the name of some Chicago citizen who had lost his wallet in a recent stickup.

An FBI agent and an officer of the Minneapolis Police Department checked these possibilities. The next day, December 16, 1942, they found Nelson in a hotel, in bed with a loaded gun under his pillow and his door barricaded with a chair. He was registered under the name of Harold Seeger. Harold Seeger, it should be noted, was a Chicago grocerman who was held up by a masked bandit on December 11, 1942, and robbed of his wallet, identification papers and pocket money.

Nelson would not talk, but the half-healed, grievous wounds on his head were a significant indication that the gang had had trouble. On the same day that Nelson was arrested, agents located Stewart.

Several days before, Stewart had made a telephone call to Milwaukee. The call was traced to a pay station telephone in a drug store on North Broadway in Chicago. Within an hour after this call was made, agents were combing that area of Chicago. Contacts were developed in hotels, barrooms, night spots, rooming houses, and restaurants. Many reliable persons, when shown Stewart’s photograph, believed that they had seen the man recently.

Finally on December 16, 1942, agents observed a known acquaintance of Stewart’s standing near a bank at the intersection of Oak Park and Harrison Streets. He was carrying a newspaper high under his left arm, rather awkwardly. To the trained observer, he had the air of a man waiting to be met by someone he did not know. The newspaper could very well be the tag by which he was to be recognized.

The agents waited. Their assumption was correct. The man did have a rendezvous but agents did not recognize the individual who came to meet him. They followed the unknown man and found that he lived in a hotel on West Harrison Street. A surveillance at the hotel soon located Stewart. He was known at the hotel as James Shea, this being the name of a man robbed of his wallet and identification papers in Chicago on November 22, 1942. He was also known as “The Deacon,” because he dressed in black and wore his clothing like a minister in an effort to disguise himself. When in public, he always carried a Bible, which he frequently opened and read.

Agents did not arrest Stewart immediately. They hoped he would lead them to Touhy and his gang. For four days there were no significant developments.

Then, on December 20, 1942, Stewart had a rendezvous with two men unknown to surveilling agents. The agents surmised that Stewart was not in direct contact with the gang and that these two men were couriers between him and Banghart. Agents quietly took Stewart into custody and followed the two couriers.

The next day, December 21, 1942, agents following one of the couriers recognized Banghart and Darlak whom the courier met in a crowded, downtown area. Agents instinctively realized what was wrapped inside the newspaper that Banghart was carrying. They also realized that it was not time to take Banghart and Darlak. They knew that Banghart, if approached on the street, would start shooting wildly and that the lives of bystanders would be imperiled. They also knew that if they took Banghart and Darlak, the search for the remaining fugitives would become even more difficult. The thing to do was to follow Banghart and Darlak until they led to the hide-out so that all five fugitives could be taken at once without endangering the lives of innocent citizens.

The surveillance on Banghart for the next seven days was most difficult. He carried his shotgun at all times and he knew all of the tricks of shaking off or detecting surveilling officers. The hazardous surveillance, however, paid off. Banghart never realized that he was being followed.

Within five days, agents had learned that the entire gang had been living in apartment number 31 at 1256 Leland Avenue, but that they were splitting into two groups. McInerney and Lanthorn were remaining in apartment number 31; Darlak, Touhy, and Banghart were moving into an apartment at 5116 Kenmore Avenue.

Only one thing remained to be done before arrangements could be made for the arrests. The agents, who had never before seen McInerney and Lanthorn, had to be absolutely certain that these were the right men before attempting the arrest, because they knew there would be gunplay. On Sunday afternoon, December 27, 1942, the two men believed to be McInerney and Lanthorn both left their apartment for a few minutes. While agents were following them on the streets, two other agents slipped into their apartment and obtained some discarded bottles which could be processed for fingerprints. In the Chicago office they developed on these bottles fingerprints identical with those of the two fugitives.

The Final Raid

Director Hoover hurried to Chicago to make final plans for the raid. In both apartment houses, unsuspecting neighbors who might be in the line of fire had to be secretly evacuated. Arrangements had to be made with the police department to block off the streets. Every conceivable means of an exit had to be covered, and the agents deployed so that they would not be caught in their own cross fire.

On Monday evening, December 28, 1942, McInerney and Lanthorn again left their apartment and went to visit the other fugitives. Two agents slipped into their room to await their return. other agents filtered into the building to cover all possible means of escape. At 11:20 p.m. the two fugitives returned. They approached the door of their apartment with their guns drawn. After a tense, listening pause before the door, Lanthorn inserted a key and threw the door open.

One of the agents in the room called for their surrender: “We are federal officers. Put your hands up.”

Both convicts fired in the direction of the voice. The agents opened fire. Both men lurched from the room, stumbled over the banister and fell dead on the second-floor landing.

On the bodies of both men were found large sums of money. In McInerney’s pockets were two strange items: (1) the address of an undertaker, and (2) a fragment of verse:

I wish I now were old enough

To give some sound advice

To make each person weigh his thoughts

And turn over twice.

I wish my eyes had seen enough

So I could make him see

The way impressions in this life

Can fool us easily.

I wish my heart had held enough

So it could not impart

The worthiest philosophy To every human heart.

Apartment building where Roger Touhy and members of his gang were captured by the FBI on December 29, 1942.

McInerney, 31, was the youngest of this group of convicts.

Director Hoover next took his men to 5116 Kenmore Avenue where they surrounded the building and took up their assigned posts in adjoining apartments. They waited until just before dawn.

At 5:00 a.m., on December 29, 1942, powerful searchlights were turned on to illuminate the apartment building and to play on the windows of the fugitives’ first-floor apartment.

As the lights went on, one of Director Hoover’s assistants began speaking into a microphone connected with a loudspeaker outside the apartment door.

“Touhy, Banghart, Darlak, we are the FBI. Surrender and come out with your hands up. There is no hope of escape. You are surrounded. You have ten minutes to decide. We will then start shooting.”

These words were repeated several times, then: “Banghart, you come out first. Come out backwards with your hands in the air. Touhy, you come out next and Darlak, you come last. Come out one at a time. Come out backwards with your hands in the air.” The agents could hear excited and muffled voices in the apartment:

“Let’s fight.”

“No! They’ve got us covered on all sides.”

“What do you say - let’s give up. I know how these guys operate!”

“Listen to that voice. It sure gives me the creeps!”

A few seconds later, Banghart backed out of the apartment, hands held high in the air, talking fast:

“Don’t do anything. Don’t do anything. Don’t worry—I won’t do anything!”

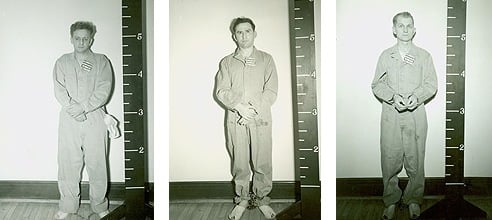

Roger Touhy, Edward Darlak, and Basil Banghart following their arrest on December 29, 1942.

He had no chance to do anything. Director Hoover seized him and he was handcuffed.

Next came Touhy, the very ghost of the once feared “Black Roger.” His curly, black hair had been peroxided to a reddish-blond and was the texture of straw. Clad in flaming red satin pajamas, he was trembling and silent as he backed out of the apartment holding his hands over his head. He stared morosely at the floor while he was being handcuffed. Darlak, as instructed, backed out last.

Banghart was the first to regain his composure. His owl-like eyes had been darting about, taking in everything that happened. He was the first to speak after all the convicts had been taken into custody.

“You’re Mr. Hoover, aren’t you? I pegged you from your picture in the paper. It’s not everybody that has the honor of having the big Chief get him.” Touhy was glum and one of the agents asked him what he was thinking. Banghart chirped a reply: “Well, Boss, he’s thinking as Molly said to Fibber the other night—it ain’t funny anymore.” On the way to the FBI office, Banghart chattered endlessly:

“We picked the wrong time for this break. A fellow has to have a Selective Service card, a Social Security card, and is hindered by too many wartime restrictions.”

After wistfully thinking it over, Banghart added: “If I had broken out two years ago, I could have gotten out of the country, maybe gone to South America and gotten a job flying.”

He even grew expansive and paid the FBI a compliment:

“Mr. Hoover,” he said, “you’ve got a good outfit. That sound chilled us. It was coming through the window, through the front door, through the back door—from all over. At first, I thought some of our enemies were out to get us.”

In connection with this investigation and the searches incidental to the arrests, FBI agents recovered a total of $13,605.84 which the gang had taken in the robbery of an armored car in north Chicago on December 18, 1942. Also recovered were stolen automobiles, guns, expensive clothing and draft and Social Security cards of persons who had been robbed.

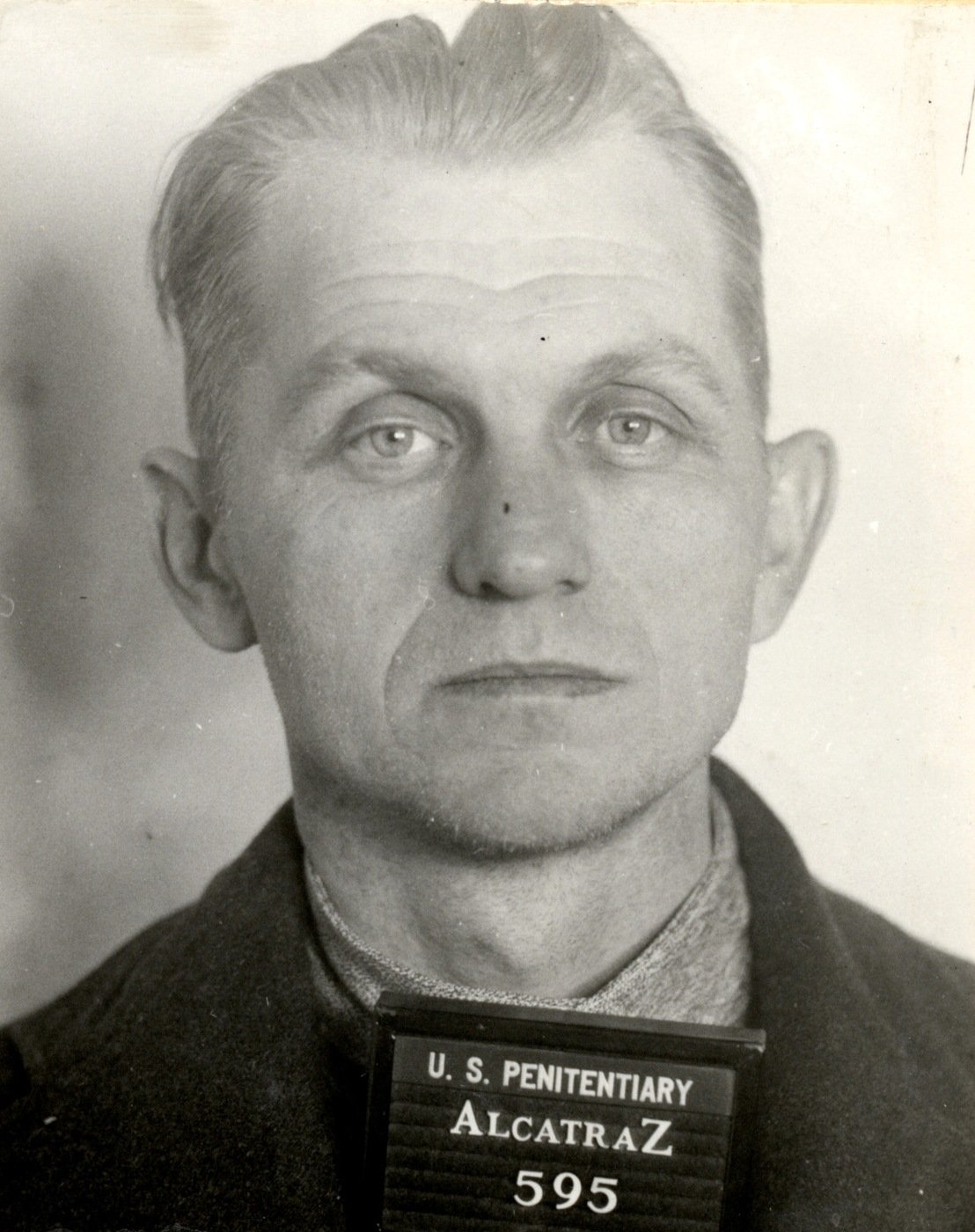

The Selective Service complaints which agents had filed in October were all dismissed. Nelson, Stewart, Darlak, and Touhy were returned to state custody. Banghart was sent to Alcatraz in January 1943.

Basil Banghart

All the way through, Banghart had been the undisputed leader of this mob.

He was born in 1900 at Berville, Michigan. He finished high school and had one year at college before he turned definitely to a career of crime. The record indicates that he stole over one hundred automobiles in and around Detroit before his first arrest and conviction in 1926.

On January 4, 1926, he was arrested in Cincinnati and returned to Detroit to stand trial for car theft. He pleaded guilty and threw himself on the mercy of the court. The judge placed him on probation for one year.

Two months later in April 1926, he was again arrested, this time in Dayton, Ohio and was charged with a violation of the National Motor Vehicle Theft Act.

He was convicted and sentenced to serve two years in the United States Penitentiary at Atlanta, Georgia, where he deliberately made the acquaintance of long-termers, making what was the equivalent of a post-graduate study in crime.

Assigned to the window washing detail, Banghart had good opportunity to saw the steel bars enclosing a window. At dusk on January 25, 1927, together with other convicts, he made his escape through the window, jumped twenty feet to the ground and made a headlong dash across an open field. Outrunning the bloodhounds, he plunged through swamps and marshes to freedom.

He made his way to Montana where he cooled off for a period before going back east to organize a business of stealing automobiles. He established a ring of car thieves which operated in and around New Jersey. Some of the stolen cars were driven south; others were sold in the same city where they had been stolen after Banghart had changed the motor and serial number.

Alcatraz booking photo of Basil Hugh Banghart in January 1943. National Archives photograph.

In October 1928, he was arrested in Pennsylvania and turned over to a United States Marshal at Pittsburgh for arraignment on a National Motor Vehicle Theft Act charge. While in the custody of the marshal in the federal building at Pittsburgh, Banghart asked permission to go to the lavatory. Walking down the corridor, he suddenly shoved the Marshal off balance and dashed out of the building, pointing in front of him and shouting, “Get the police.” Stop that man!” The ruse worked and Banghart made good his escape. Two weeks later, however, he was arrested in Philadelphia. In that two weeks he had dyed his hair, shaved his moustache, and put on glasses.

He was returned to Atlanta and served out his sentence, which expired on February 14, 1930. When he left, however, he did not go free. He was taken into custody on a detainer and removed to Knoxville where he was confined in the Knox County Jail to await prosecution in federal court. He made an unsuccessful attempt to escape from this jail. When he was tried he pleaded guilty and asked for probation, saying that he had never had a chance to go straight. The judge, however, sentenced him to two more years in the penitentiary at Atlanta.

Banghart served this sentence, but in January 1932, less than two months after his release, he was arrested in Detroit as a robbery suspect. He was released to local authorities at South Bend, Indiana, for prosecution on an armed robbery that had occurred in that city in 1927. On his way to South Bend, Banghart boasted that he had belonged to the Purple Gang in Detroit and that the South Bend Jail could not keep him long. He was right. On March 27, 1932, he blinded a turnkey with pepper, took his jail keys, seized a machine gun, and shot his way out of jail.

It was at this point that he fled to Chicago and became a machine gunner and top leader of the Touhy mob, at that time engaged in an underworld war with the Capone interests.

In 1933, accompanied by his paramour and two of the Touhy gangsters, he left Chicago and hid out for a while in Tennessee, ultimately moving to Charlotte, North Carolina. In November of that year, Banghart and his two henchmen robbed a United States mail truck at Charlotte, obtaining $120,000. He was next arrested in a fashionable apartment in Baltimore, Maryland, on February 10, 1934.

After standing trial in Chicago for participating in the Factor kidnapping and standing trial at Asheville, North Carolina, for participating in the mail robbery, he was returned to Illinois and incarcerated in the state prison at Menard to serve the 99 years for the sentence that he had drawn for the Factor kidnapping.

On October 2, 1935, he and other inmates at Menard assaulted prison guards and, in a commandeered truck, crashed through the prison gates. Banghart was soon recaptured and, as previously pointed out, was sent to Joliet to complete his sentence.

Both Banghart and Touhy were eventually released from prison following rulings that challenged the legitimacy of the Factor kidnapping investigation. Touhy was killed just a few weeks after his release in 1959. Banghart died in 1982.