Nazi Saboteurs and George Dasch

Shortly after midnight on the morning of June 13, 1942, four men landed on a beach near Amagansett, Long Island, New York from a German submarine.

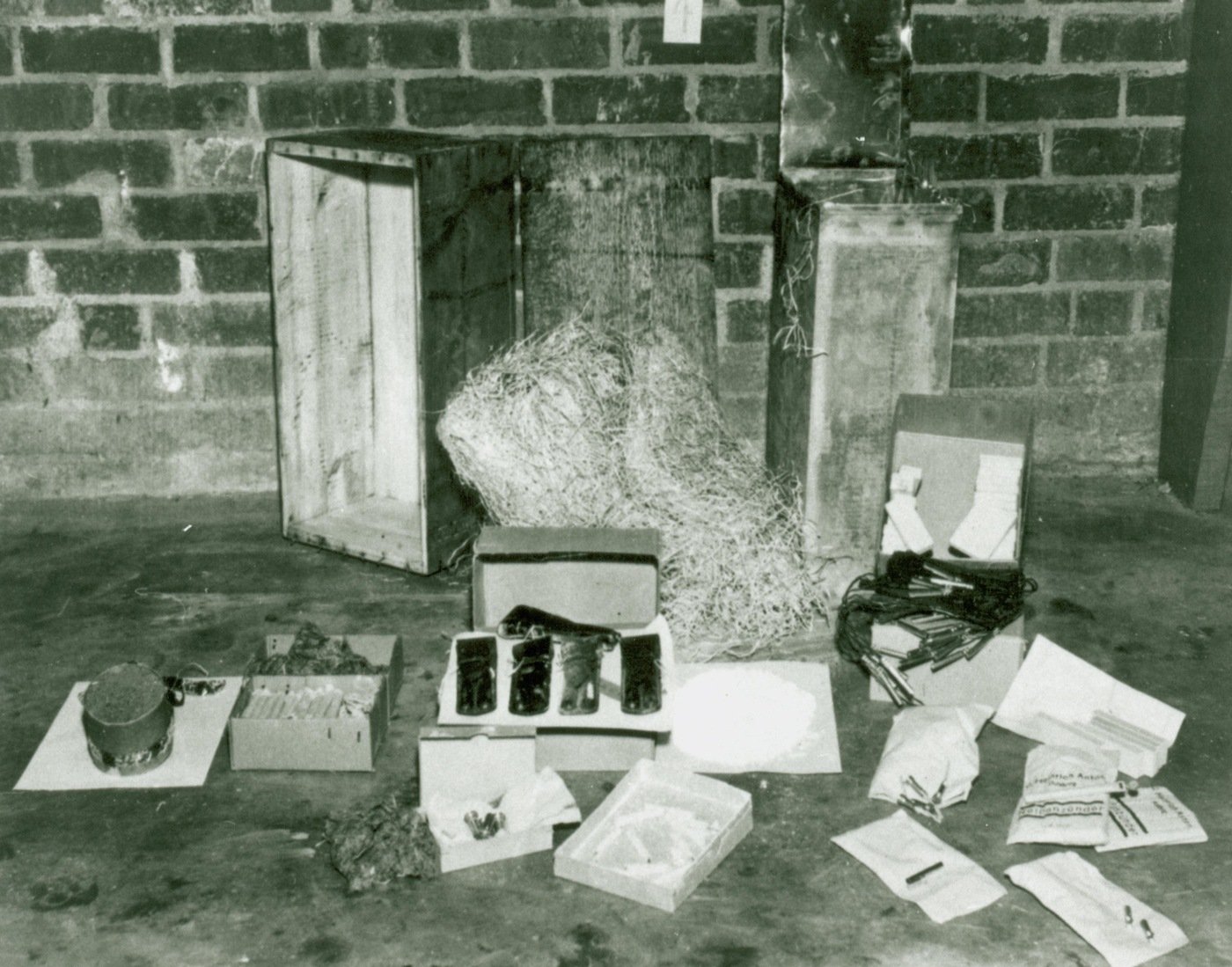

They were clad in German uniforms and bringing ashore enough explosives, primers, and incendiaries to support an expected two-year career in the sabotage of American defense-related production.

On June 17, 1942, a similar group landed on Ponte Vedra Beach, near Jacksonville, Florida, equipped for a similar career in industrial disruption.

The purpose of the invasions was to strike a major blow for Germany by bringing the violence of war to our home ground through destruction of America’s ability to manufacture vital equipment and supplies and transport them to the battlegrounds of Europe; to strike fear into the American civilian population; and to diminish the resolve of the United States to overcome our enemies.

By June 27, 1942, all eight saboteurs had been arrested without having accomplished one act of destruction. Tried before a military commission, they were found guilty. One was sentenced to life imprisonment, another to 30 years, and six received the death penalty, which was carried out within a few days.

The magnitude of the euphoric expectation of the Nazi war machine may be judged by the fact that, in addition to the large amount of material brought ashore by the saboteurs, they were given $175,200 in United States currency to finance their activities. On apprehension, a total of $174,588 was recovered by the FBI—the only positive accomplishment of eight trained saboteurs in those two weeks was the expenditure of $612 for clothing, meals, lodging, and travel, as well as a bribe of $260.

So shaken was the German intelligence service that no similar sabotage attempt was ever again made. The German naval high command did not again allow a valuable submarine to be risked for a sabotage mission.

The Plan

On September 1, 1939, World War II opened in Europe with the invasion of Poland by Nazi Germany. The United States remained neutral until drawn into the world conflict by the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941. War was declared against Japan by the United States on December 8, 1941; and, on the 11th, Germany and Italy declared war against the United States.

During the early months of the war, the major contributions of the United States to oppose the Nazi war machine involved industrial production, equipment, and supplies furnished to those forces actively defending themselves against the German armed forces. That industrial effort was strong enough to generate frustration, perhaps indignation, among the Nazi high command; and the order was given, allegedly by Hitler himself, to mount a serious effort to reduce American production.

German intelligence settled on sabotage as the most effective means of diminishing our input. In active charge of the project was Lieutenant Walter Kappe, attached to Abwehr-2 (Intelligence 2) who had spent some years in the United States prior to the war and had been active in the German-American Bund and other efforts in the United States to propagandize and win adherents for Nazism among German Americans and German immigrants in America. Kappe was also an official of the Ausland Institute, which, prior to the war, organized Germans abroad into the Nationalsozialistiche Deutshe Arbeiterpartei, the NSDAP or Nazi Party, and during the conflict, Ausland kept track of and in touch with persons in Germany who had returned from abroad. Kappe’s responsibility concerned those who had returned from the United States.

Early in 1942, he contacted, among others, those who ultimately undertook the mission to the United States. Each consented to the task, apparently willingly, although unaware of the specific assignment. Most of the potential saboteurs were taken from civilian jobs, but two were in the German army.

The trainees, about 12 in all, were told of their specific mission only when they entered a sabotage school established near Berlin which instructed them in chemistry, incendiaries, explosives, timing devices, secret writing, and concealment of identity by blending into an American background. The intensive training included the practical use of the techniques under realistic conditions.

Subsequently, the saboteurs were taken to aluminum and magnesium plants, railroad shops, canals, locks, and other facilities to familiarize them with the vital points and vulnerabilities of the types of targets they were to attack. Maps were used to locate those American targets, spots where railroads could be most effectively disabled, the principal aluminum and magnesium plants, and important canals, waterways, and locks. All instructions had to be memorized.

The Landing

On May 26, 1942, the first group of four saboteurs left by submarine from the German base at Lorient, France, and on May 28, the next group of four departed the same base. Each was destined to land at points on the Atlantic Coast of the United States familiar to the leader of that group.

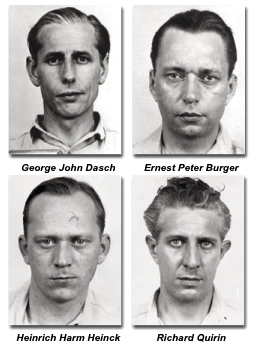

Four men, led by George John Dasch, age 39, landed on a beach near Amagansett, Long Island, New York, about 12:10 a.m., June 13, 1942. Accompanying Dasch were Ernest Peter Burger, 36; Heinrich Harm Heinck, 35; and Richard Quirin, 34.

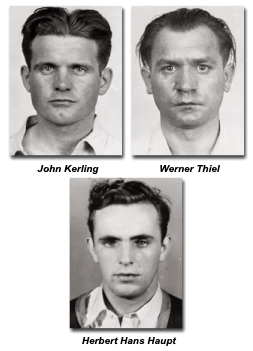

On June 17, 1942, the other group landed at Ponte Vedra Beach, Florida, south of Jacksonville. The leader was Edward John Kerling, age 33; with Werner Thiel, 35; Herman Otto Neubauer, 32; and Herbert Hans Haupt, 22. Both groups landed wearing complete or partial German uniforms to ensure treatment as prisoners of war rather than as spies if they were caught in the act of landing.

Having landed unobserved, the uniforms were quickly discarded, to be buried with the sabotage material (which was intended to be later retrieved), and civilian clothing was donned. The saboteurs quickly dispersed. The Florida group made their way to Jacksonville, then by train to Cincinnati, with two going on to Chicago and the other pair to New York City.

The Arrests

The Long Island group was less fortunate; scarcely had they buried their equipment and uniforms, in fact, one still wore bathing trunks, when a Coast Guardsman patrolling the shore approached. He was unarmed and very suspicious of them, more so when they offered him a bribe to forget they had met. He ostensibly accepted the bribe to lull their fears and promptly reported the incident to his headquarters. However, by the time the search patrol located the spot, the saboteurs had reached a railroad station and had taken a train to New York City.

Dasch’s resolution to be a saboteur for the Fatherland faltered—perhaps he thought the whole project so grandiose as to be impractical and wanted to protect himself before some of his companions took action on similar doubts. He indicated to Burger his desire to confess everything.

On the evening of June 14, 1942, Dasch, giving the name “Pastorius” called the New York Office of the FBI stating he had recently arrived from Germany and would call FBI Headquarters when he was in Washington, D.C., the following week. On the morning of Friday, June 19, a call was received at the FBI Washington from Dasch, then registered at a Washington hotel. He alluded to his prior call as “Pastorius” (of which Headquarters was aware) and furnished his location. He was immediately contacted and taken into custody.

During the next several days he was thoroughly interrogated and he furnished the identities of the other saboteurs, possible locations for some, and data which would enable their more expeditious apprehension.

The three remaining members of the Long Island group were picked up in New York City on June 20. Of the Florida group, Kerling and Thiel were arrested in New York City on June 23, and Neubauer and Haupt were arrested in Chicago on June 27.

The Trial

The eight were tried before a military commission, comprised of seven U.S. Army officers appointed by President Roosevelt, from July 8 to August 4, 1942.

The trial was held in the Department of Justice Building, Washington, D.C. The prosecution was headed by Attorney General Frances Biddle and the Army Judge Advocate General, Major General Myron C. Cramer. Defense counsel included Colonel Kenneth C. Royall (later Secretary of War under President Truman) and Major Lausen H. Stone (son of Harlan Fiske Stone, the Chief Justice of the U.S. Supreme Court).

All eight were found guilty and sentenced to death. Attorney General Biddle and J. Edgar Hoover appealed to President Roosevelt to commute the sentences of Dasch and Burger. Dasch then received a 30-year sentence, and Burger received a life sentence, both to be served in a federal penitentiary. The remaining six were executed at the District of Columbia Jail on August 8, 1942.

The eight men had been born in Germany and each had lived in the United States for substantial periods. Burger had become a naturalized American in 1933. Haupt had entered the United States as a child, gaining citizenship when his father was naturalized in 1930.

Dasch had joined the Germany army at the age of 14 and served about 11 months as a clerk during the conclusion of World War I. He had enlisted in the U.S. Army in 1927 and received an honorable discharge after a little more than a year of service.

Quirin and Heinck had returned to Germany prior to the outbreak of World War II in Europe, and the six others subsequent to September 11, 1939 and before December 7, 1941 apparently feeling their first loyalty was to the country of their birth.

The special seven-man military commission opens the third day of its proceedings in the trial of eight Nazi saboteurs in the fifth floor courtroom of the Department of Justice building in July 1942. Sitting on the commission left to right are: Brigadier General John T. Lewis; Major General Lorenzo D. Casser; Major General Walter S. Grant; Major General Frank R. McCoy, president of the commission; Major General Blanton Winship; Brigadier General Guy V. Henry; and Brigadier General John T. Kennedy. All eight were found guilty. Library of Congress photograph.

Postwar debriefing of German personnel and examination of records confirmed that no other attempt was made to land saboteurs by submarine; though in late 1944, two persons, William Curtis Colepaugh and Erich Gimpel, were landed as spies from a German submarine on the coast of Maine in a rather desperate attempt to secure information. They, too, were quickly apprehended by the FBI before accomplishing any part of their mission.

In April 1948, President Truman granted executive clemency to Dasch and Burger on condition of deportation. They were transported to the American Zone of Germany, the unexecuted portions of their sentences were suspended upon such conditions with respect to travel, employment, political, and other activities as the Theater commander might require, and they were freed.

Although many allegations of sabotage were investigated by the FBI during World War II, not one instance was found of enemy-inspired sabotage. Every suspect act traced to its source was the result of vandalism, pique, resentment, a desire for relief from boredom, the curiosity of children “to see what would happen,” or other personal motive.