John Elgin Johnson

On September 25, 1953, Special Agent John Brady Murphy of the Baltimore office was shot to death while pursuing John Elgin Johnson, a murder suspect and long-time criminal.

The FBI had tracked Johnson to a Baltimore theater, where he opened fire, killing Agent Murphy and wounding another agent. The agents returned fire, killing Johnson.

Johnson’s Early Criminal Career

The circumstances of Johnson’s childhood existence are not fully known. He was born in Linn Grove, Iowa, to a large family, on August 21, 1919, and was reared in the northwestern United States.

After completion of the tenth grade at Cody, Wyoming, however, he made his initial thrust into a claim for recognition. He was arrested and convicted for larceny at Rapid City, South Dakota, on November 23, 1935. At the age of 16, the first step towards his zenith of violence had begun. But society, realizing that youth has but youthful philosophy, granted him probation.

Just three months later, young Johnson was again arrested, this time at Santa Fe, New Mexico, where, for breaking and entering, he was sentenced on February 2, 1936, to serve from eighteen months to two years. After 11 months’ confinement, he was released.

Under the alias of Eric Vernon Jefferson, his fast-rising career was again served when he was arrested for investigation of car prowling at Salt Lake City, Utah, on March 2, 1937. Thus, in 15 months the embryonic murderer was rapidly familiarizing himself with the judicial and penal systems.

With the exactness of a migrant bird, Johnson returned to the dubious warmth of the underworld’s “nest.” On August 16, 1938, he was apprehended by local Los Angeles authorities on charges of burglary which resulted in his removal to Rawlins, Wyoming, where the crime had occurred. With almost monotonous repetition, Johnson, now a worldly 19, was sentenced to serve from two to three years. Twenty-three months later, in August 1940, Johnson returned to society.

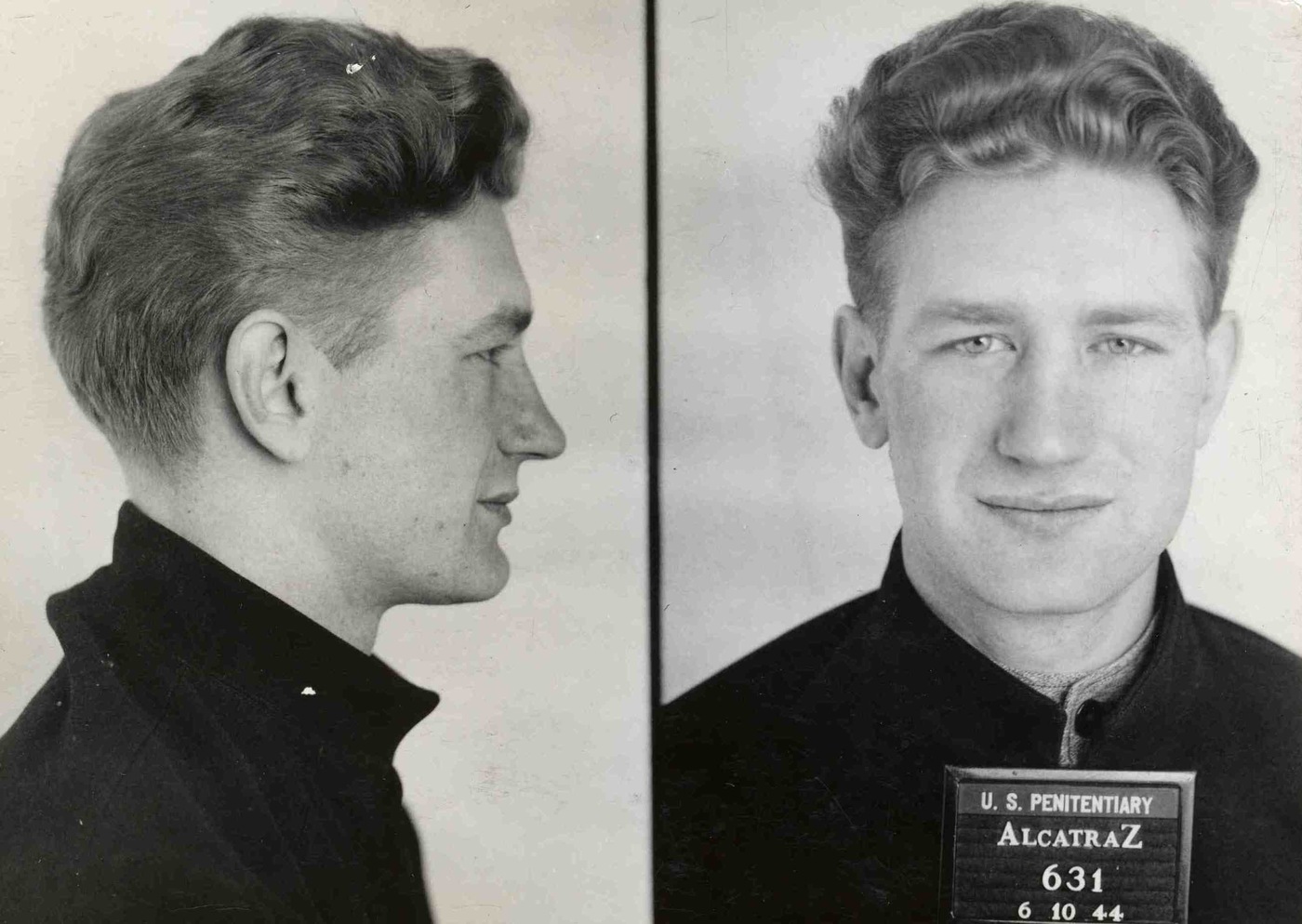

Booking photo of John Elgin Johnson when he arrived at Alcatraz prison on June 10, 1944. National Archives photograph.

On this day the Hollywood Branch of the Citizens National Trust and Savings Bank was conducting its normal daily business. Shortly after the noon hour a young man entered the bank and approached the first teller’s cage. He was directed by the manager to the second teller. At the second teller’s window the young man handed over a number of small bills, stating that it was $80, for which he wanted four $20 bills. As he was being handled the larger bills, he pulled a gun and said, “Give me the rest.” The teller handed over $610 to the young gunman who wheeled and ran from the bank.

FBI agents and the Los Angeles Police Department began an immediate investigation of the robbery. Extensive neighborhood investigations were undertaken. It was on this same day, however, that three other bank robberies took place in Los Angeles. A minor crime wave had befallen the city. In usual investigative fashion, several immediate suspects were developed from among known criminals in the Los Angeles area. John Elgin Johnson was not among them.

On October 28, 1940, information was received by the Los Angeles FBI Office from the Des Moines, Iowa, FBI Office, which revealed that a John Elgin Johnson had been apprehended by the Sioux City, Iowa, Police Department after robbing a department store in that city. Among his effects was located a newspaper account of the bank robberies in Los Angeles on September 17, 1940.

The method of operation used in the Iowa robbery and the similarity of that bandit’s description to the Los Angeles bank bandit were immediately noted by FBI agents handling the case. It was quickly determined that on September 17, 1940, Johnson had purchased a 1939 Mercury Sedan. With it he purchased a new car radio and two new tires. He paid approximately $300 in cash. He was known to have been night-clubbing, picking up more than his share of the checks. Johnson’s picture was obtained and displayed to officials of the four banks which had been robbed.

He was tentatively identified at two banks as being the lone bandit who committed the robberies on September 17, 1940. Again Johnson, who had been free from law enforcement for less than three months, was about to re-enter prison life.

Faced with the evidence against him, Johnson admitted to FBI agents at Des Moines, Iowa, that he had perpetrated the Los Angeles bank robberies, but ironically enough, he confessed to all four committed on September 17, 1940. Later investigation eliminated Johnson from two of the robberies. The criminal mind was quick to claim the “glory” attached to someone else’s share of crime.

Federal justice moved rapidly for Johnson. He was returned to Los Angeles, California, where, on November 27, 1940, he was indicted by a federal grand jury on two counts of bank robbery. Entering a plea of guilty in United States District Court, Los Angeles, he was sentenced on December 23, 1940, to two 15-year sentences to be served concurrently. The United States Penitentiary, McNeil Island, Washington, received Johnson shortly thereafter—his third prison term at 21 years of age.

Within the whispering society constituting a prison life, Johnson was also a misfit. After Johnson was transferred for disciplinary reasons to U.S. Prison, Leavenworth, Kansas to serve the remainder of his time for bank robbery conviction, his twisted thinking once again guided towards disaster. Shortly after his arrival at Leavenworth, Johnson, together with two other inmates, attempted to escape and in so doing assaulted prison guards. Again the man who had repeatedly shown his contempt for the society around him was fighting to re-enter it. This act resulted in Johnson’s being found guilty by a Kansas jury on April 18, 1944, of assault with intent to kill a federal officer. He was given a sentence of four years and recommended for transfer to the U.S. Penitentiary at Alcatraz, San Francisco, California.

After nine years of almost uninterrupted criminal activity, on June 10, 1944, Johnson arrived at Alcatraz. He was placed with America’s toughest criminals—the “select” group who defy rehabilitation to the utmost. John Elgin Johnson was to take his place with the sullen breed who populate “The Rock.”

The unbending discipline must have been torturous to a mind as unregulated and undisciplined as Johnson’s. But his mind yet sought a chink in the structure. Johnson became known as a regular attendant at the church services. He became a devoted visitor to his spiritual advisor and continually sought baptism into religion. The advisor, sympathetic but vigilant against emotional desire for conversion, did not grant Johnson’s request. Johnson began taking instructions for this faith in a correspondence course from a middle western university. The chaplain, in later years, related to FBI agents that Johnson’s ready grasp of the faith’s spiritual qualities was amazing. Johnson became so imbued with the principles, or so it appeared, that he expressed strong desire to entering the religious life as a lay brother. This ambition, as it turned out, never reached full bloom.

It is difficult to imagine what Johnson actually learned at Alcatraz, but, in his own words, he learned to hate. In nine years Johnson must have heard thousands of innocence pleas from “framed” prisoners. His own mind might have been seething with vitriolic condemnation of the forces that kept him in vigilant tow. Perhaps it was here that he heard of “FBI agents’ cruelty,” for he later stated “The FBI stinks—they hold guys out of windows and even sometimes let them drop!”

Johnson’s tutelage was complete. He now hated society, hated law enforcement, probably hated himself. He was now ready for his greatest coup. It eventually came.

A Free Man

It could have been a typically gray San Francisco day when Johnson crossed the choppy bay from Alcatraz.

It was March 20, 1953, and he had been granted a conditional release from Alcatraz. He had undoubtedly shaken hands with several prison officials, received a small cash allowance, and was ordered to report to the Los Angeles Federal Probation Office. He was free. Or was he? Could he forget almost 17 years of detention? He was 34 now. He had a form of trade since he had learned plumbing and machine-shop work in prison. He headed towards Los Angeles, the city of his choosing, to begin again. Begin what? Only Johnson knew.

Johnson’s arrival at Los Angeles, California, was not notably different from other ex-convicts arriving in the area. He registered at the Los Angeles Police Department as an ex-convict on March 21, 1953, as California law demands. He contacted the Federal Probation Office and apparently set out on the road to rehabilitation. He located his former prison chaplain, then assigned to Los Angeles.

He also approached the assistant city editor of the Los Angeles Mirror, Sid Hughes, from whom Johnson requested aid in securing a driver’s license. Johnson related to the newspaperman some tales of hardships at Alcatraz and other details concerning innocent men being held there. Hughes became interested in Johnson’s rehabilitation and secured for him a California driver’s permit, and Hughes allowed him to travel around in a Mirror-owned car while preparing for his test. Because of his interest in Johnson, benevolent Hughes aided him in securing a position with a heater company located in a Los Angeles suburb, Huntington Park.

For approximately the next three months Johnson’s release seemed to vindicate the faith placed in him. He was not reported in any criminal activity. He registered with the Huntington Park Police Department on April 22, 1953, as an ex-convict and apparently had joined the little-heralded group who compose society’s basic core.

Wanted for Murder

On July 19, 1953, information was received by the Robbery Detail of the Los Angeles Sheriff’s Office that an individual had appeared at a Los Angeles County supermarket introducing himself to the manager as “Watkins, Los Angeles Police Department, Chain Store Robbery Detail.” This “police officer” made inquiries concerning the location of store funds, the amounts, and when it was taken to the bank. He also confided to the manager a tip that the market was to be robbed. The “policeman’s” line of questioning finally aroused the suspicion of the manager who noted that the man had entered a red convertible. The grocer jotted down the California license number.

Subsequent investigation by the Los Angeles Sheriff’s Office determined that the red convertible was owned by a resident of Huntington Park, California. The owner had recently purchased the Ford but had not yet secured a driver’s license. Meanwhile, it had been loaned to a few recently befriended men, among them one John Elgin Johnson.

Sheriff’s deputies located Johnson’s police record and displayed his photograph to the supermarket owner. Johnson was identified as “Watkins of the Los Angeles Police Department.” The hater had adopted the guise of the hated in this, his newest venture in crime. Unfortunately, however, Los Angeles law enforcement was destined to hear of something much grimmer in just a few days.

On August 4, 1953, at approximately 5:40 p.m., Lieutenant Kenyon Kendrick of the Huntington Park Police Department was called to a local residence to investigate the discovery of a body. At this address, lying garroted in the bottom of his stall shower, was discovered the body of the owner of the red convertible. He had been strangled with a necktie tied neatly in a square knot. John Elgin Johnson, his former companion, was not to be found for questioning.

The murder victim’s landlord related to police that he had been painting screens on the building on August 1, 1953, when he overheard a conversation between the victim and a “tall, reddish-blond-haired fellow,” who stated: “I feel sorry for you, you’ve done a lot for me.” Johnson’s picture was soon identified by the landlord as being the described individual last seen with the victim.

Further investigation disclosed that the deceased had been seen by a couple on August 2, 1953, in the company of several men in his back yard. One of the men was merely described as being tall. At this point in the investigation, the Huntington Park Police Department believed they had two prime suspects in the murder, one being John Elgin Johnson. The other was arrested five days later but furnished a substantial alibi for his whereabouts at the time of the murder. Johnson became the lone and prime suspect. But he was still not available for interview. His whereabouts was unknown.

On the Run

Eventually, information came to the attention of the Huntington Park Police Department that a letter addressed to one of Johnson’s former residences bore the return address of Arthur Dawson (Fictitious), Box 920, Reg. #66032, Hall B, Jefferson City, Missouri, postmarked July 30, 1953. Swift checking revealed that this same Dawson was one of the two men who had been involved with Johnson in the attempted break from Leavenworth nine years previously. Dawson was incarcerated in the Missouri State Penitentiary, Jefferson City, Missouri, and Johnson was apparently retaining his membership in crime’s lost legion.

On August 31, 1953, information received from the Jefferson City Penitentiary indicated that Dawson had received a letter postmarked at Cincinnati, Ohio, but bearing the return address of Frank Gifford and a residence in Florida. The body of the message stated: “Received letter from our mutual friend, John.” It also contained a $50 money order for Dawson.

The FBI entered the search for John Elgin Johnson when a request was received from the United States Board of Parole, Washington, D.C., stating that on August 10, 1953, John Elgin Johnson, with aliases, had a conditional release violator’s warrant issued against him, charging him with loss of contact, associating with persons having criminal backgrounds, impersonating a police officer, auto theft, and alleged murder. Four months after a last look at the gray gloom of Alcatraz, Johnson chose a return passport.

Coupling their investigation, the Huntington Park Police Department made available to FBI agents at Los Angeles the most recent accounting of Johnson’s activities. Local investigation proved momentarily fruitless as to his location. Acting upon the information concerning the receipt of a letter by Johnson’s convict friend, Dawson, a request was promptly relayed to the Miami FBI Office to determine the identity of Frank Gifford at the Florida address.

This investigation failed to show that a Frank Gifford had ever resided at the given address, but it was revealed that the residence was occupied by a Johnson family, soon discovered to be the parents of John Elgin Johnson.

On September 22, 1953, Johnson’s father was interviewed by FBI agents. He stated that Johnson, for the first time in many years, had visited his parents just four days prior and had left their home on September 21, 1953, saying he was “heading north and then back to Los Angeles.” The alertness of a West Coast police officer, and the rapid teamwork of the FBI, had reached across the United States and placed themselves just one day behind Johnson.

Johnson had related to his parents that he was on parole and was undoubtedly violating it but felt that he “might be railroaded back in California since they found an associate of mine murdered.” He commented, too, on his bitter experiences at Alcatraz and how he was attempting to go straight—just waiting for the chance to clear his name. Exhaustive interviews with the cooperative parents did not furnish any logical lead as to Johnson’s whereabouts. The search continued, but without success.

Meanwhile, reports were being received at the Los Angeles FBI Office which placed Johnson in the midwest during mid-August in 1953. FBI agents from the Milwaukee Office had determined that one John Everhardt had resided in a Chicago hotel on or about August 15, 1953. It was related that Everhardt had bragged to a stranger about his release from Alcatraz several months previous. Everhardt, finally identified as John Elgin Johnson, was living true to form. So true and accurate that he displayed to this stranger a P-38 pistol! Johnson told this individual of his early experiences in crime and during his bragging conversations said, “They will never take me back to prison.” The prophecy of a warped mind was not to go unnoticed.

According to this information an eventful shadow was being cast, for when Johnson heard the elevator stop at his room floor, he would grasp his gun and on two occasions walked into the hallway, gun in hand, to determine who had gotten off the elevator. Johnson, who told his parents several weeks later he wanted to clear his name, was more than ready to greet any opposition in the fashion he knew best.

Call From Baltimore

On September 25, 1953, Sidney Hughes, veteran Los Angeles Mirror reporter, received a telephone call from Baltimore, Maryland. The caller was Johnson.

The newspaperman had earlier tried to help Johnson by assisting him in obtaining a job after Johnson’s release from Alcatraz. Hughes, who received the call at about 2:30 p.m., Los Angeles time notified the FBI Office there as soon as the call was completed. Hughes said that Johnson had told of being in Baltimore with $10,000 which he had received from a friend to set Johnson up in business. Johnson wanted to know if he was wanted or sought in Los Angeles, California, as he desired to return there and enter a business. Hughes, thinking quickly, told Johnson that he would have to check to determine this information. He requested Johnson to call him back at exactly 3:35 p.m. Johnson agreed.

The Los Angeles FBI Office instantly relayed this information to the Baltimore FBI Office. A manhunt was instituted to locate Johnson somewhere in Baltimore. The information at hand: a description, a knowledge that he was using a telephone. A battle of time was declared.

Back in Los Angeles, 3,000 miles away, FBI agents established an open line between their office and the newspaper room. Thus a strange quadrangular relationship began—Hughes, a known factor; Johnson, an unknown factor; and two teams of FBI agents closely allied by knowledge and training, but separated by a continent’s width.

At 3:55 p.m., Pacific Daylight Saving Time, 20 minutes later than scheduled, Sid Hughes received another call from Baltimore, a call which was the end not quite as expected. A pre-arranged plan with the Mirror’s switchboard operator stalled momentarily the salutatory greeting. Finally the conversation began. FBI, Baltimore, was alerted—the call was in progress! Feverish activity began at Baltimore to pinpoint the fugitive.

Hughes, careful to give no indication that he was stalling, began enticing Johnson into a lengthy conversation. They talked at the outset about Johnson’s running away. Johnson would only state that he was waiting for the Huntington Park murder to clear up. They talked about the $10,000 which Johnson had received. He replied, “It was from a legitimate source.” Johnson was pressed for his location. He would only state that he was near Baltimore.

Johnson queried as to Hughes’ reporting the conversation. He pushed the point, saying, “You’ll have to report it.” The criminal intuition was at work, too.

Johnson expressed surprise that the murder had not been cleared. Hughes, as instructed, tried to determine from Johnson who some of the murdered victim’s friends were. Johnson was evasive, only describing some “Johnny” who lived nearby.

The conversation progressed. It was 4:30 p.m., Los Angeles time. In Baltimore, squads of FBI agents continued to comb the downtown area.

Veteran reporter Hughes recounted with Johnson the experiences which Johnson had earlier told him of Alcatraz. Johnson related that he would not spend an hour back in prison as it taught him how to hate. He admitted having a gun. Hughes pleaded with him to throw it away. Hughes requested him to turn himself in to the FBI. Johnson replied, “They stink. They hold guys out of windows and even let them drop.” The years in prison culture were at work.

It was 4:35 p.m., Pacific time. Still talking—still looking.

The conversation at times was jocular, mostly serious. Hughes was subtly endeavoring to determine the fugitive’s exact location. Johnson continued to remain evasive.

“I’m in Washington, D.C., and have visited the Smithsonian Institute and other buildings,” Johnson said, and “I’m going to let the whole thing ride for a month or so, as I am still afraid of the Huntington Park murder.”

Fatal Shoot-Out

At 4:44 p.m., Hughes had still not received from Johnson any hint as to his exact whereabouts, but back in Baltimore the battle of time was nearing decision. Five minutes earlier the FBI had learned that Johnson was in the Towne Theatre, a motion picture house in the heart of downtown Baltimore. A crowd had turned out to see the Mickey Spillane murder mystery, “I, The Jury,” but the mezzanine, where the public telephone was located, was almost deserted.

Upon learning of Johnson’s location, four agents nearby proceeded immediately to the theatre. On their arrival they learned that the mezzanine, which was closed to the evening’s patrons, was accessible by means of two stairways. The agents divided, two of them proceeding cautiously up each stairway.

One of the FBI men was Special Agent J. Brady Murphy. As he and his companion reached the lobby of the mezzanine almost simultaneously with the other two agents, they observed that only one person was on the mezzanine—a man in the telephone booth.

Inside the booth, Johnson, his criminal cunning ever alert, sensed his impending apprehension. Two shots rang out from the booth. One bullet crashed into the abdomen of J. Brady Murphy. Another tore into the hip of Murphy’s fellow agent. All four agents opened fire on the phone booth; though mortally wounded, Agent Murphy emptied his revolver at the figure of the desperate man behind the glass and wood partition. Fifteen times the agents fired, and 15 deadly slugs ripped into the booth. Johnson toppled toward the floor, but his head, crashing through the broken glass of the door, held him partly erect. Before he stopped moving forever he tried vainly once or twice to lift his head.

Back in Los Angeles, Sid Hughes had been talking to Johnson for almost 50 minutes when he heard, as he described it later, “commotion and the sound of coins ringing in the telephone pay slot.” The line went dead. The Baltimore operator said, “I am sorry, sir, your party’s line seems to be out of order.”

Special Agent J. Brady Murphy

At the Towne Theatre, FBI agents had to remove the door of the phone booth in order to extricate Johnson’s body. The receiver still dangled from the telephone, and a P-38 automatic slipped from Johnson’s hand. He had been hit seven times by the agents’ gunfire, in the stomach, head, chest, and shoulder. He was pronounced dead on arrival at a nearby hospital.

Meanwhile, J. Brady Murphy and the other wounded agent were also rushed to a hospital, where the latter eventually recovered fully. But Murphy, just before going on the operating table, sensed that he was about to die. He inquired about Johnson and was told that the criminal was dead. The dying prayer which left the agent’s lips was a measure of the vast difference between the two men: “May God have mercy on his soul,” said J. Brady Murphy of John Elgin Johnson, murderer.