Hollow Nickel/Rudolf Abel

One of the nation’s most fascinating—and ultimately significant—spy cases began in the summer of 1953, when a Brooklyn newspaper boy dropped a nickel he had just earned.

When he picked it up, almost like magic, the coin split in half. Inside was a tiny photograph, showing a series of numbers too small to read.

Here’s how the investigation unfolded.

The Discovery

On the evening of Monday, June 22, 1953, a delivery boy for the “Brooklyn Eagle” knocked on the door of one of his customers in the apartment building at 3403 Foster Avenue in Brooklyn. It was “collecting time” again. A lady answered the door. She disappeared for a moment, then returned with a purse in her hand.

“Sorry, Jimmy,” she said. “I don’t have any change. Can you break this dollar bill for me?”

The newsboy quickly counted the coins in his pocket. There were not enough. “I’ll ask the people across the hall,” he said.

There were two ladies in the apartment across from the one occupied by Jimmy’s customer. By pooling the coins in their pocketbooks, they were able to give the newsboy change for a dollar.

After he collected for the newspaper, Jimmy left the apartment house jingling several coins in his left hand. One of the coins seemed to have a peculiar ring. The newsboy rested this coin, a nickel, on the middle finger of his hand. It felt lighter than an ordinary nickel.

He dropped this coin to the floor. It fell apart!

Inside was a tiny photograph—apparently a picture of a series of numbers.

Two days later, on June 24, 1953, during a discussion of another investigation, a detective of the New York City Police Department told an FBI agent about the strange hollow nickel which, he had heard, was discovered by a Brooklyn youth. The detective had received his information from another police officer whose daughter was acquainted with the newsboy.

When the New York detective contacted him, Jimmy handed over the hollow nickel and the photograph it contained. The detective, in turn, gave the coin to the FBI.

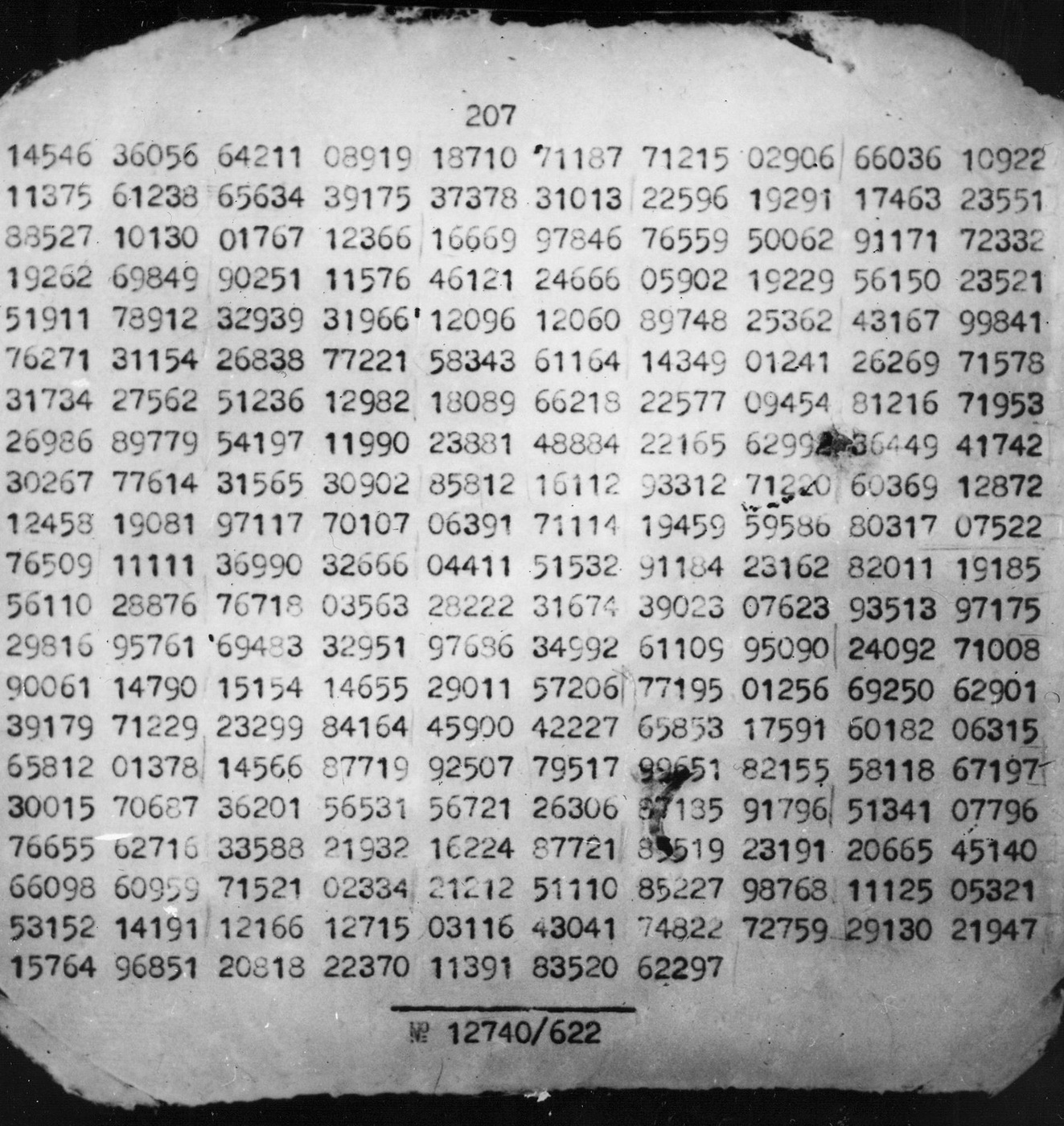

In examining the nickel, agents of the FBI’s New York Office noted that the microphotograph appeared to portray nothing more then ten columns of typewritten numbers. There was five digits in each number and 21 numbers in most columns. The agents immediately suspected that they had found a coded espionage message. They carefully wrapped the nickel and microphotograph for shipment to the FBI Laboratory.

Upon its receipt in Washington on June 26, 1953, the nickel was subjected to the thorough scrutiny of a team of FBI scientific experts. Hollow coins, though rarely seen by the ordinary citizen, are occasionally used in magic acts and come to the attention of federal law enforcement agencies from time to time. This was the first time, however, that the FBI had ever encountered a nickel quite like this one.

The hollow nickel found by the Brooklyn newspaper boy

The coded message contained in the hollow nickel

The face of the coin was a 1948 Jefferson nickel. In the “R” of the word “TRUST”, there was a tiny hole—obviously drilled there so that a fine needle or other small instrument could be inserted to force the nickel open.

The reverse side had been made from another nickel—one minted sometime during the period of 1942 to 1945. It was composed of copper-silver alloy, there being a shortage of nickel during World War II.

Search for the Coin’s Source

While efforts were being made to decode the message on the microphotograph, FBI agents in New York launched an investigation to find the source of the hollow coin.

The two ladies who had changed the newboy’s dollar on the evening of June 22 were located. Yes, they remembered Jimmy; but, if either had given him a hollow nickel, it was entirely unintentional. “Why, we’ve never seen a hollow coin—or, for that matter, even heard of one before.”

The proprietors of novelty stores and related business establishments in the New York vicinity were contacted. Photographs of the hollow coin were shown to them. None could recall seeing a nickel or other coin quite like this one.

“It’s not suitable for a magic trick,” one novelty salesman commented. “The hollowed-out area is too small to hide anything aside from a tiny piece of paper.

In Washington, each effort to decipher the microphotograph met with failure. Additionally, the kind of typewriter which had been used in preparing the coded message could not be identified. Since the FBI Laboratory maintains a reference file concerning typewriters manufactured in the United States, a foreign-made typewriter undoubtedly was involved.

From 1953 to 1957, continuing efforts were made to solve the mystery of the hollow coin. Several former intelligence agents who had defected to the free world from communist-bloc nations were contacted. They could shed no light on the case.

As the search for the source of the hollow nickel expanded across the United States, hollow subway tokens, “trick” coins, and similar objects were submitted to the FBI Laboratory by agents in various parts of the country. From New York came a half dollar which had been ground in such a manner that smaller coins could be concealed under it. From Los Angeles came a peculiar-looking 1953 Lincoln penny. FBI scientists determined that it had been coated with nickel.

Two hollow pennies were found in Washington, D.C. Neither of these pennies, nor the assortment of other coins which the Laboratory examined, was found to have tool markings or other distinguishing features to identify it with the newsboy’s 1948 Jefferson nickel.

In the intelligence and counterintelligence field, patience is more than a virtue. It is an absolute necessity. Months of determined probing by the FBI’s scientists and investigative staff had led merely to one blind alley after another. Yet, the relentless search to identify the person who had brought the hollow nickel to New York, as well as the person for whom the coded message was intended, continued.

Defection of a Russian Spy

The key to this mystery proved to be a 36-year-old Lieutenant Colonel of the Soviet State Security Service (KGB).

Early in May 1957, he telephoned the United States Embassy in Paris and subsequently arrived at the embassy to be interviewed. To an embassy official, the Russian espionage agent explained, “I’m an officer in the Soviet intelligence service. For the past five years, I have been operating in the United States. Now I need your help.”

This spy, Reino Hayhanen, stated that he had just been ordered to return to Moscow. After five years in the United States, he dreaded the thought of going back to his communist-ruled homeland. He wanted to defect—to desert the Soviet camp.

Hayhanen was born near Leningrad on May 14, 1920. His parents were peasants. Despite his modest background, Hayhanen was an honor student and, in 1939, obtained the equivalent of a certificate to teach high school.

In September 1939, Hayhanen was appointed to the primary school faculty in the Village of Lipitzi. Two months later, however, he was conscripted by the Communists’ secret police, the NKVD. Since he had studied the Finnish language and was very proficient in its use, Hayhanen was assigned as an interpreter to an NKVD group and sent to the combat zone to translate captured documents and interrogate prisoners during the Finnish-Soviet war.

With the end of this war in 1940, Hayhanen was assigned to check the loyalty and reliability of Soviet workers in Finland and to develop informants and sources of information in their midst. His primary objective was to identify anti-Soviet elements among the intelligentsia.

Hayhanen became a respected expert in Finnish intelligence matters and in May 1943 was accepted into membership in the Soviet Communist Party. Following World War II, he rose to the rank of senior operative authorized representative of the Segozerski district section of the NKGB and, with headquarters in the Village of Padani, set about the task of identifying dissident elements among the local citizens.

In the summer of 1948, Hayhanen was called to Moscow by the KGB. The Soviet intelligence service had a new assignment for Hayhanen—one which would require him to sever relations with his family, to study the English language, and to receive special training in photographing documents, as well as to encode and decode messages.

While his KGB training continued, Hayhanen worked as a mechanic in the City of Valga, Estonia. Then, in the summer of 1949, he entered Finland as Eugene Nicolai Maki, an American-born laborer.

Background of the Real Maki

The real Eugene Nicolai Maki was born in Enaville, Idaho on May 30, 1919. His mother also was American born, but his father had immigrated to the United States from Finland in 1905. In the mid-1920s, Eugene Maki’s parents became deeply impressed by glowing reports of conditions in “the new” Russia. They sold their belongings and left their Idaho farm for New York to book passage on a ship to Europe.

After leaving the United States, the Maki family settled in Estonia. From the outset, it was obvious that they had found no “Utopia” on the border of the Soviet Union. Letters that they wrote to their former neighbors showed that Mr. and Mrs. Maki were very unhappy and sorely missed America.

As the years passed, memories of the Maki family gradually began to fade, and all but possibly two or three old time residents of Enaville, Idaho, forgot that there has ever been a Maki family in that area. In Moscow, however, plans were being made for a “new” Eugene Maki, one thoroughly grounded in Soviet intelligence techniques, to enter the scene.

Hayhanen Becomes Maki

From July 1949 to October 1952, Hayhanen resided in Finland and established his identity as the American-born Eugene Maki. During this period, he was most cautious to avoid suspicion or attracting attention to himself—his Soviet superiors wanting him to become established as an ordinary, hard-working citizen. This false “build up,” of course, was merely part of Hayhanen’s preparation for a new espionage assignment.

While in Finland, Hayhanen met and married Hanna Kurikka. She was to join him in the United States on February 20, 1953—four months after his arrival here. Even his wife knew him only as Eugene Maki, so carefully did he cover his previous life.

On July 3, 1951, Hayhanen—then living in Turku, Finland—visited the United States Legation in Helsinki. He displayed a birth certificate from the state of Idaho which showed that he was born in Enaville on May 30, 1919, and, in the presence of a Vice Consul, he executed an affidavit in which he explained that his family had left the United States in 1928:

“I accompanied my mother to Estonia when I was eight years of age and resided with her until her death in 1941. I left Estonia for Finland in June 1943, and have resided here for the reason that I have no funds with which to pay my transportation to the United States.”

One year later—July 28, 1952—a passport was issued to Hayhanen as Eugene Maki at Helsinki. Using this passport, he sailed October 16, 1952 from Southhampton, England aboard the Queen Mary and arrived at New York City on October 21, 1952.

Several weeks before he departed for America, Hayhanen was recalled to Moscow and introduced to a Soviet agent, “Mikhail,” who was to serve as his espionage superior in this country. In order to establish contact with “Mikhail” in the United States, Hayhanen was instructed that after arriving in New York he should go to the Tavern on the Green in Central Park. Near the tavern, he was told, he would find a signpost marked “Horse Carts”

“You will let Mikhail know of your arrival by placing a red thumb tack in this signpost,” a Soviet official told him. “If you suspect that you are under surveillance, place a white thumb tack on the board.”

Hayhanen Returns to the United States

The information which Hayhanen furnished to U.S. officials in Paris, France, in May 1957, was immediately checked. There could be no question of its accuracy. Accordingly, passage was secured for Hayhanen on an airliner, and he was permitted to return to the United States.

Following his arrival in New York on May 10, 1957, Hayhanen was given a thorough physical examination, suitable quarters were found for him, and arrangements were made for him to be interviewed by FBI agents.

From the fall of 1952 until early in 1954, he said, “Mikhail” served as his espionage superior in New York. They met only when necessary—the meeting place being the Prospect Park subway station. To exchange messages and intelligence data, they used “dead drops”—inconspicuous hiding places—in the New York area. One of these “dead drops” was an iron picket fence at the end of 7th Avenue near Macombs bridge. Another was the base of a lamp post in Fort Tryon Park.

In one of the “dead drops” mentioned by Hayhanen—a hole in a set of cement steps in Prospect Park—FBI agents found a hollowed-out bolt. The bolt was about two inches long and one-fourth inch in diameter. It contained the following typewritten message:

“Nobody came to meeting either 8 or 9th...as I was advised he should. Why? Should he be inside or outside? Is time wrong? Place seems right. Please check.”

The bolt was found on May 15, 1957. It had been placed in the “dead drop” about two years previously, but, by a trick of fate, a repair crew had filled the hole in the stairs with cement, entombing the bolt and the message it contained.

Questioned about the hollow bolt, Hayhanen said that “trick” containers such as this were often used by the espionage apparatus which he served. Among the items he had been supplied by the Soviets were hollow pens, pencils, screws, batteries, and coins—in some instances magnetized so they would adhere to metal objects.

Hollow 50 Markka Coin

In the modest home of Hayhanen and his wife on Dorislee Drive in Peekskill, New York, FBI agents found such items as a 50 Markka coin from Finland. It had been hollowed out, and there was a small hole in the first “a” of the word “Tasavalta” which appeared on the “tail side” of this coin.

FBI Laboratory experts examined this Finnish coin on May 17, 1957. They immediately noted that it bore a great similarity to the Jefferson nickel which the Brooklyn newsboy had discovered in 1953. Two separate coins obviously had been used in making this “trick” 50 Markka piece. This also was the case with the hollow nickel. And both coins had a small hole in one printed letter so that a sharp-pointed instrument, such as a needle, could be used to open them.

Although the FBI was convinced that it had finally identified the Soviet espionage apparatus which was responsible for the hollow Jefferson nickel, only one half of the mystery posed by this coin since its discovery in June 1953 had been solved. The coded message which the nickel contained still had to be deciphered.

During the FBI’s extensive interviews with him, in May 1957 Hayhanen was carefully questioned regarding the codes and cryptosystems which he had used in the various Soviet intelligence agencies he had served since 1939. The information which he provided was applied by FBI Laboratory experts to the microphotograph from the Jefferson nickel.

With this data, the FBI Laboratory succeeded in breaking through the curtain of mystery which surrounded the coded message. By June 3, 1957, the full text of the microphotograph was known. The message apparently was intended for Hayhanen and had been sent from the Soviet Union shortly after his arrival in the United States. It read:

“1. WE CONGRATULATE YOU ON A SAFE ARRIVAL. WE CONFIRM THE RECEIPT OF YOUR LETTER TO THE ADDRESS `V REPEAT V’ AND THE READING OF LETTER NUMBER 1.”

“2. FOR ORGANIZATION OF COVER, WE GAVE INSTRUCTIONS TO TRANSMIT TO YOU THREE THOUSAND IN LOCAL (CURRENCY). CONSULT WITH US PRIOR TO INVESTING IT IN ANY KIND OF BUSINESS, ADVISING THE CHARACTER OF THIS BUSINESS.”

“3. ACCORDING TO YOUR REQUEST, WE WILL TRANSMIT THE FORMULA FOR THE PREPARATION OF SOFT FILM AND NEWS SEPARATELY, TOGETHER WITH (YOUR) MOTHER’S LETTER.”

“4. IT IS TOO EARLY TO SEND YOU THE GAMMAS. ENCIPHER SHORT LETTERS, BUT THE LONGER ONES MAKE WITH INSERTIONS. ALL THE DATA ABOUT YOURSELF, PLACE OF WORK, ADDRESS, ETC., MUST NOT BE TRANSMITTED IN ONE CIPHER MESSAGE. TRANSMIT INSERTIONS SEPARATELY.”

“5. THE PACKAGE WAS DELIVERED TO YOUR WIFE PERSONALLY. EVERYTHING IS ALL RIGHT WITH THE FAMILY. WE WISH YOU SUCCESS. GREETINGS FROM THE COMRADES. NUMBER 1, 3RD OF DECEMBER.”

Other Soviet Agents

Although Hayhanen assisted the FBI in solving the mystery of the hollow nickel, the information he furnished placed other critical challenges before the agents. “Mikhail,” the Soviet with whom Hayhanen maintained contact from the fall of 1952 until early 1954, was yet to be identified. And, when “Mikhail” dropped from the scene in 1954, Hayhanen was turned over to another Russian spy, one known only as “Mark.” Hayhanen felt that “Mark” undoubtedly was still actively engaged in espionage within the United States! He also must be identified.

Hayhanen obtained the impression that “Mikhail” was a Soviet diplomatic official—possibly attached to the embassy or the United Nations. He described “Mikhail” as probably between 40 and 50 years old; medium build; long, thin nose; dark hair; and about five feet, nine inches tall. This description was matched against the descriptions of Soviet representatives who had been in the United States between 1952 and 1954. From the long list of possible suspects, the most logical “candidate” appeared to be Mikhail Nikolaevich Svirin.

Svirin had been in and out of the United States on several occasions between 1939 and 1956. From the latter part of August 1952 until April 1954, he had served as the first secretary to the Soviet United Nations Delegation in New York.

On May 16, 1957, FBI agents showed a group of photographs to Hayhanen. The moment his eyes fell upon a picture of Mikhail Nikolaevich Svirin, Hayhanen straightened up in his chair and announced, “That’s the one. There is absolutely no doubt about it. That’s Mikhail.”

Svirin was beyond reach of American justice. He had returned to the Soviet Union in October 1956.

The FBI’s next task was to identify “Mark,” the Soviet agent who had succeeded “Mikhail” as Hayhanen’s contact man. Hayhanen did not know where “Mark” was residing or the name which “Mark” was using; however, he was able to furnish many other details concerning him.

According to Hayhanen, “Mark” was a colonel in the KGB and had been engaged in espionage work since approximately 1927. He had come to the United States in 1948 or 1949, entering by illegally crossing the Canadian border.

In keeping with instructions contained in a message he received from Soviet officials, Hayhanen was met by “Mark” at a movie theater in Flushing, Long Island, during the late summer of 1954. As identification symbols, Hayhanen wore a blue and red striped tie and smoked a pipe.

After their “introduction” at this theater, Hayhanen and “Mark” held frequent meetings in Prospect Park, on crowded streets, and in other inconspicuous places in the area of Greater New York. They also made several short trips together to Atlantic City, Philadelphia, Albany, Greenwich, and other communities in the eastern part of the United States.

“Mark” also sent Hayhanen on trips alone. For example, in 1954, “Mark” instructed him to locate an American Army sergeant, one formerly assigned to the United States Embassy in Moscow. At the time he related this information to FBI agents in May 1957, Hayhanen could not remember the Army sergeant’s name. “I do recall, however, that we used the code name `Quebec’ in referring to him and that he was recruited for Soviet intelligence work while in Moscow.”

(An intensive investigation was launched to identify and locate “Quebec.” It quickly produced results when, in examining a hollow piece of steel from Hayhanen’s home, the FBI Laboratory discovered a piece of microfilm less than one-inch square. The microfilm bore a typewritten message which identified “Quebec” as Army sergeant Roy Rhodes and stated the Soviet agents had recruited him in January 1952. Full information concerning Rhodes’ involvement in Russian espionage was disseminated to the Army; and following a court-martial, he was sentenced to serve five years at hard labor.)

Hayhanen described “Mark” as about 50 years old or possibly older; approximately five feet ten inches tall; thin gray hair; and medium build. The unidentified Soviet agent was an accomplished photographer, and Hayhanen recalled that on one occasion in 1955, “Mark” took him to a storage room where he kept photo supplies on the fourth or fifth floor of a building located near Clark and Fulton Streets in Brooklyn.

The search for this storage room led FBI agents to a building at 252 Fulton Street. Among the tenants was one Emil R. Goldfus, a photographer who had operated a studio on the fifth floor since January, 1954—and who also had formerly rented a fifth-floor storage room there.

In April 1957 (the same month Hayhanen boarded a ship for Europe under instructions to return to Moscow), Goldfus had told a few persons in the Fulton Street building that he was going South on a seven-week vacation. “It’s doctor’s orders,” he explained. “I have a sinus condition.”

Goldfus disappeared about April 26, 1957. Less than three weeks later, FBI agents arrived at 252 Fulton Street in pursuit of the mysterious “Mark.” Since Goldfus appeared to answer the description of Hayhanen’s espionage superior, surveillance was established near his photo studio.

On May 28, 1957, agents observed a man resembling “Mark” on a bench in a park directly opposite the entrance to 252 Fulton Street. This man occasionally walked about the park; he appeared to be nervous; and he created the impression that he was looking for someone—possibly attempting to determine any unusual activity in the neighborhood. At 6:50 p.m., this man departed on foot—the agents, certain their presence had not been detected, chose to wait rather than take a chance of trailing the wrong man. “If that’s `Mark,’ he’ll return,” they correctly surmised.

While the surveillance continued at 252 Fulton Street, other FBI agents made daily checks on the “dead drops” that Hayhanen stated he and “Mark” had used. The agents’ long hours of patience were rewarded on the night of June 13, 1957. At 10:00 p.m., they saw the lights go on in Goldfus’ studio, and a man was observed moving in the room.

The lights went out at 11:52 p.m., and a man who appeared to generally fit the description of “Mark” stepped into the darkness outside the building. This man was followed down Fulton Street to a nearby subway station. Moments later, FBI agents saw him take a subway to 28th Street, and they stood by unnoticed as he emerged from the subway and walked to the Hotel Latham on East 28th Street.

On June 15, a photograph of Goldfus which the FBI took with a hidden camera was shown to Hayhanen. “You’ve found him,” the former Soviet Agent exclaimed. “That’s ‘Mark.’”

Goldfus—registered at the Hotel Latham under the name of Martin Collins—was kept under surveillance from the night of June 13 until the morning of June 21, 1957. During this period, FBI agents discreetly tied together the loose ends of the investigation, matters which had to be resolved before this Russian intelligence officer could be taken into custody.

Mark’s Arrest

Arrested by the Immigration and Naturalization Service on an alien warrant based upon his illegal entry into the United States and failure to register as an alien, “Mark” displayed a defiant attitude. He refused to cooperate at all.

Following his arrest, “Mark” was found to possess many false papers, including two American birth certificates. The first showed that he was Emil R. Goldfus, born August 2, 1902 in New York City. According to the second one, he was Martin Collins, born June 2, 1897, also in New York. Investigation was to establish that the Emil Goldfus whose birth certificate “Mark” displayed had died in infancy. The certificate in the name of Collins was a forgery.

During his career as a soviet spy, “Mark” also had used many other nabel in addition to the ones cited above. For example, during the fall of 1948, while en route to the United States from the Soviet Union, he had adopted the identity of Andrew Kayotis. The real Andrew Kayotis, believed to have died in a Lithuanian hospital, was born in Lithuania on October 10, 1895. He had arrived in the United States in October 1916 and became a naturalized American citizen at Grand Rapids, Michigan on December 30, 1930.

On July 15, 1947, Andrew Kayotis, then residing in Detroit, was issued a passport so that he could visit relatives in Europe. Investigation in Detroit disclosed that several persons there considered Kayotis to be in poor physical condition at the time of his departure from the United States. Letters subsequently received from him indicated that he was in a Lithuanian hospital. When Kayotis’ friends in Michigan heard no more from him, they assumed that he had passed away.

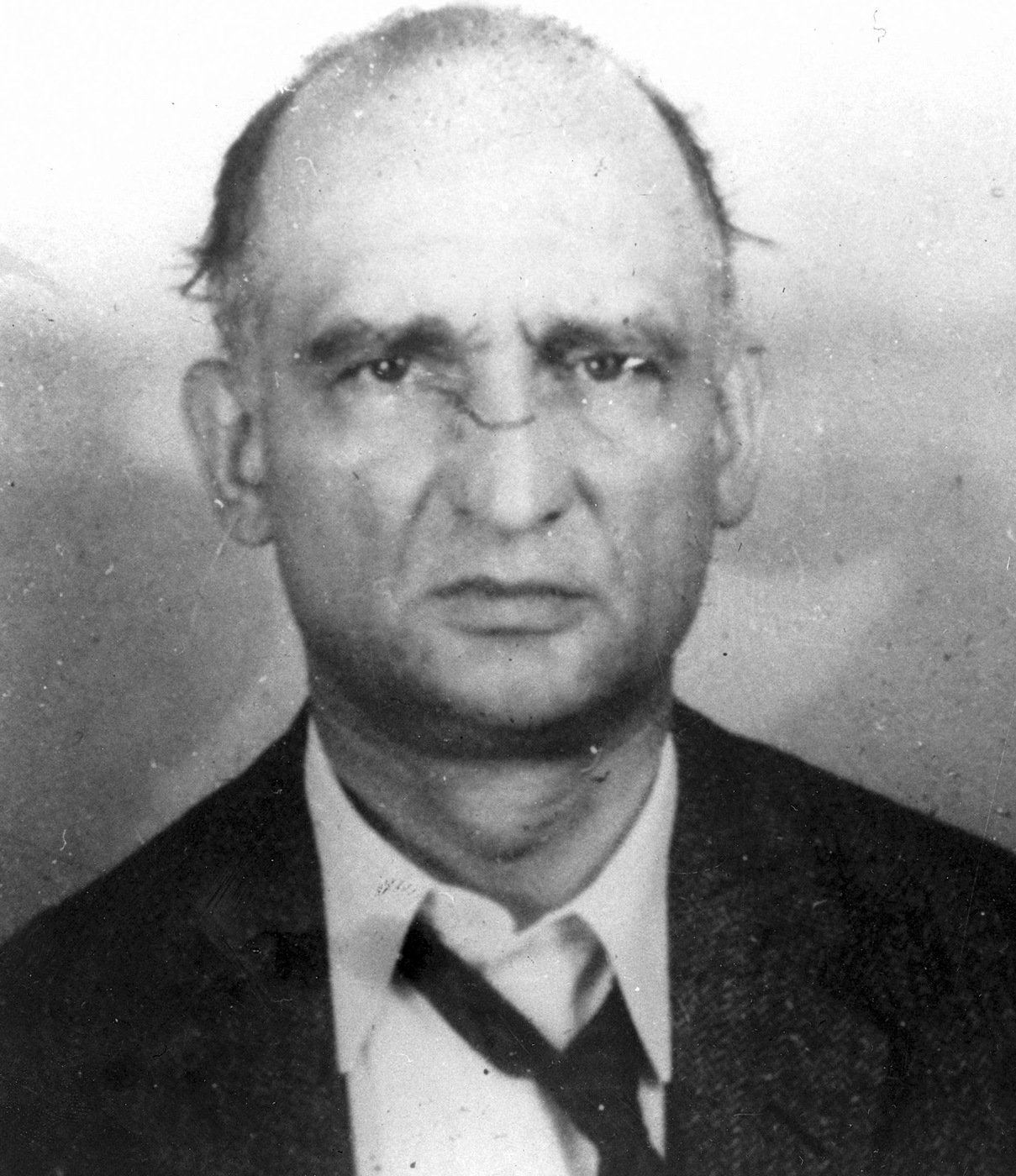

Rudolf Ivanovich Abel

Mark’s Real Identity

Nearly 10 years later, “Mark” was to admit that he had used Kayotis’ passport during the fall of 1948 in booking passage aboard an ocean liner from LeHavre, France, to Canada. On November 14, 1948, he disembarked from the ship at Quebec—and quickly dropped out of sight.

“Mark” made another admission—that he was a Russian citizen, Rudolf Ivanovich Abel, born July 2, 1902 in the Soviet Union.

Although he refused to discuss his intelligence activities, the photo studio and hotel room which he occupied were virtual museums of modern espionage equipment. They contained shortwave radios, cipher pads, cameras and film for producing microdots, a hollow shaving brush, cuff links, and numerous other “trick” containers.

Indicted as a Russian spy, Colonel Abel was tried in federal court at New York City during October 1957. Among the government witnesses to testify against him was his former trusted espionage assistant, Lieutenant Colonel Reino Hayhanen.

The Conclusion

On October 25, 1957, the jury announced its verdict—Abel was guilty of all counts.

He appeared before Judge Mortimer W. Byers on November 15, 1957 and was sentenced as follows (the three sentences to be served concurrently):

- Count One (Conspiracy to transmit defense information to the Soviet Union), 30 years’ imprisonment.

- Count Two (Conspiracy to obtain defense information), 10 years’ imprisonment and $2,000 fine.

- Count Three (Conspiracy to act in the United States as an agent of a foreign government without notification to the Secretary of State), five years’ imprisonment and $1,000 fine.

Colonel Abel appealed his convictions, claiming that rights guaranteed to him under the Constitution and laws of the United States had been violated. By a five-to-four decision which was handed down on March 28, 1960, the Supreme Court upheld the conviction of this Russian spy.

An investigation which had started with a newsboy’s hollow nickel ultimately resulted in the smashing of a Soviet spy ring. On February 10, 1962, Rudolf Invanovich Abel was exchanged for the American U-2 pilot, Francis Gary Powers, who was a prisoner of the Soviet Union.