Brink’s Robbery

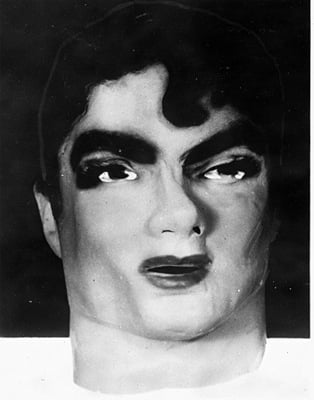

Captain Marvel mask used as a disguise in the robbery

On the evening of January 17, 1950, employees of the security firm Brinks, Inc., in Boston, Massachusetts, were closing for the day, returning sacks of undelivered cash, checks, and other material to the company safe on the second floor.

Shortly before 7:30 p.m., they were surprised by five men—heavily disguised, quiet as mice, wearing gloves to avoid leaving fingerprints and soft shoes to muffle noise. The thieves quickly bound the employees and began hauling away the loot.

Within minutes, they’d stolen more than $1.2 million in cash and another $1.5 million in checks and other securities, making it the largest robbery in the U.S. at the time.

The Investigation

As the robbers sped from the scene, a Brink’s employee telephoned the Boston Police Department. Minutes later, police arrived at the Brink’s building, and special agents of the FBI quickly joined in the investigation.

At the outset, very few facts were available to the investigators. From interviews with the five employees whom the criminals had confronted, it was learned that between five and seven robbers had entered the building. All of them wore Navy-type peacoats, gloves, and chauffeur’s caps. Each robber’s face was completely concealed behind a Halloween-type mask. To muffle their footsteps, one of the gang wore crepe-soled shoes, and the others wore rubbers.

The robbers did little talking. They moved with a studied precision which suggested that the crime had been carefully planned and rehearsed in the preceding months. Somehow the criminals had opened at least three—and possibly four—locked doors to gain entrance to the second floor of Brink’s, where the five employees were engaged in their nightly chore of checking and storing the money collected from Brink’s customers that day.

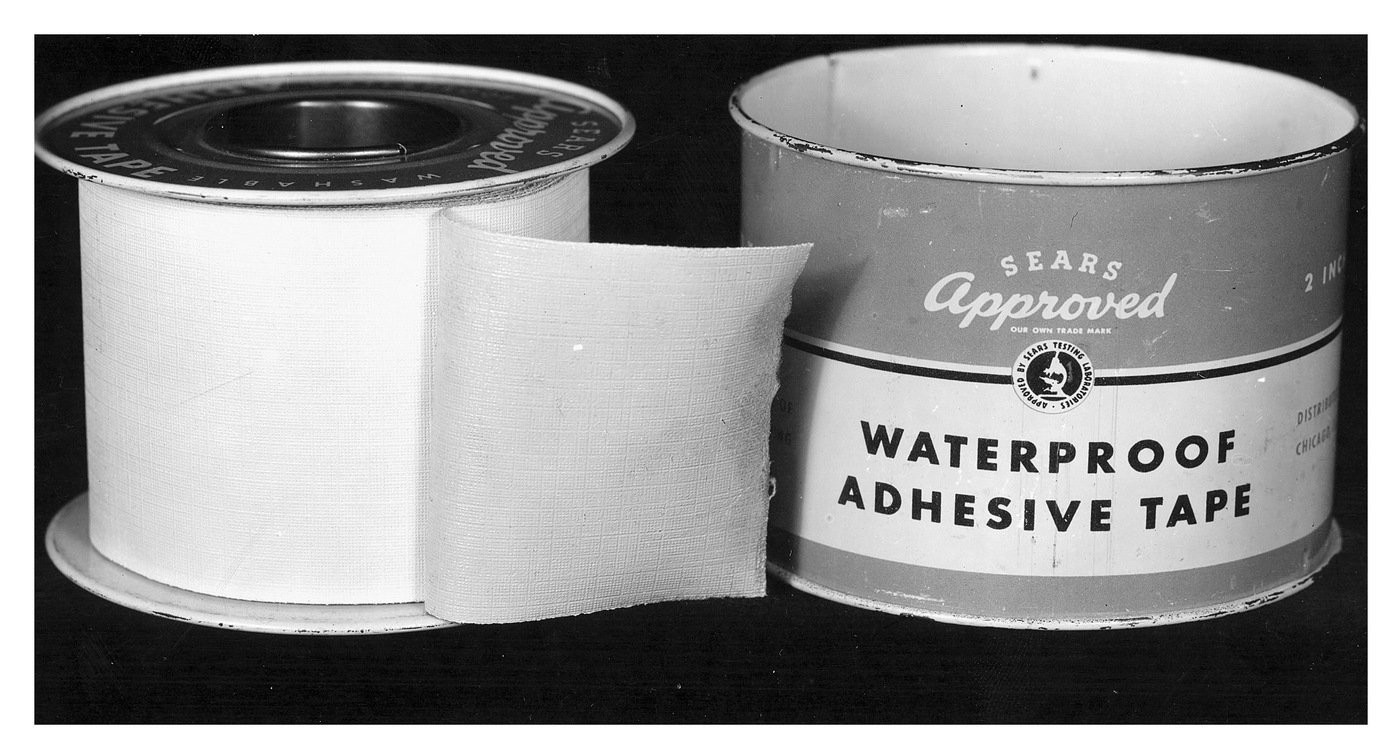

All five employees had been forced at gunpoint to lie face down on the floor. Their hands were tied behind their backs and adhesive tape was placed over their mouths. During this operation, one of the employees had lost his glasses; they later could not be found on the Brink’s premises.

As the loot was being placed in bags and stacked between the second and third doors leading to the Prince Street entrance, a buzzer sounded. The robbers removed the adhesive tape from the mouth of one employee and learned that the buzzer signified that someone wanted to enter the vault area. The person ringing the buzzer was a garage attendant. Two of the gang members moved toward the door to capture him; but, seeing the garage attendant walk away apparently unaware that the robbery was being committed, they did not pursue him.

In addition to the general descriptions received from the Brink’s employees, the investigators obtained several pieces of physical evidence. There were the rope and adhesive tape used to bind and gag the employees and a chauffeur’s cap that one of the robbers had left at the crime scene.

A roll of waterproof adhesive tape used to gag and bind bank employees that was left at the scene of the crime

The FBI further learned that four revolvers had been taken by the gang. The descriptions and serial numbers of these weapons were carefully noted since they might prove a valuable link to the men responsible for the crime.

In the hours immediately following the robbery, the underworld began to feel the heat of the investigation. Well-known Boston hoodlums were picked up and questioned by police. From Boston, the pressure quickly spread to other cities. Veteran criminals throughout the United States found their activities during mid-January the subject of official inquiry.

Since Brink’s was located in a heavily populated tenement section, many hours were consumed in interviews to locate persons in the neighborhood who might possess information of possible value. A systematic check of current and past Brink’s employees was undertaken; personnel of the three-story building housing the Brink’s offices were questioned; inquiries were made concerning salesmen, messengers, and others who had called at Brink’s and might know its physical layout as well as its operational procedures.

An immediate effort also was made to obtain descriptive data concerning the missing cash and securities. Brink’s customers were contacted for information regarding the packaging and shipping materials they used. All identifying marks placed on currency and securities by the customers were noted, and appropriate “stops” were placed at banking institutions across the nation.

Hundreds of Dead Ends

The Brink’s case was “front page” news. Even before Brink’s, Incorporated, offered a $100,000 reward for information leading to the arrest and conviction of the persons responsible, the case had captured the imagination of millions of Americans. Well-meaning persons throughout the country began sending the FBI tips and theories which they hoped would assist in the investigation.

For example, from a citizen in California came the suggestion that the loot might be concealed in the Atlantic Ocean near Boston. (A detailed survey of the Boston waterfront previously had been made by the FBI.) Former inmates of penal institutions reported conversations they had overheard while incarcerated which concerned the robbing of Brink’s. Each of these leads was checked out. None proved fruitful.

Many other types of information were received. A man of modest means in Bayonne, New Jersey, was reported to be spending large sums of money in night clubs, buying new automobiles, and otherwise exhibiting newly found wealth. A thorough investigation was made concerning his whereabouts on the evening of January 17, 1950. He was not involved in the Brink’s robbery.

Rumors from the underworld pointed suspicion at several criminal gangs. Members of the “Purple Gang” of the 1930s found that there was renewed interest in their activities. Another old gang that had specialized in hijacking bootlegged whiskey in the Boston area during Prohibition became the subject of inquiries. Again, the FBI’s investigation resulted merely in the elimination of more possible suspects.

Many “tips” were received from anonymous persons. On the night of January 17, 1952—exactly two years after the crime occurred—the FBI’s Boston Office received an anonymous telephone call from an individual who claimed he was sending a letter identifying the Brink’s robbers. Information received from this individual linked nine well-known hoodlums with the crime. After careful checking, the FBI eliminated eight of the suspects. The ninth man had long been a principal suspect. He later was to be arrested as a member of the robbery gang.

Of the hundreds of New England hoodlums contacted by FBI agents in the weeks immediately following the robbery, few were willing to be interviewed. Occasionally, an offender who was facing a prison term would boast that he had “hot” information. “You get me released, and I’ll solve the case in no time,” these criminals would claim.

One Massachusetts racketeer, a man whose moral code mirrored his long years in the underworld, confided to the agents who were interviewing him, “If I knew who pulled the job, I wouldn’t be talking to you now because I’d be too busy trying to figure a way to lay my hands on some of the loot.”

In its determination to overlook no possibility, the FBI contacted various resorts throughout the United States for information concerning persons known to possess unusually large sums of money following the robbery. Race tracks and gambling establishments also were covered in the hope of finding some of the loot in circulation. This phase of the investigation greatly disturbed many gamblers. A number of them discontinued their operations; others indicated a strong desire that the robbers be identified and apprehended.

The mass of information gathered during the early weeks of the investigation was continuously sifted. All efforts to identify the gang members through the chauffeur’s hat, the rope, and the adhesive tape which had been left in Brink’s proved unsuccessful.

On February 5, 1950, however, a police officer in Somerville, Massachusetts, recovered one of the four revolvers that had been taken by the robbers. Investigation established that this gun, together with another rusty revolver, had been found on February 4, 1950, by a group of boys who were playing on a sand bar at the edge of the Mystic River in Somerville.

Shortly after these two guns were found, one of them was placed in a trash barrel and was taken to the city dump. The other gun was picked up by the officer and identified as having been taken during the Brink’s robbery. A detailed search for additional weapons was made at the Mystic River. The results were negative.

Through the interviews of persons in the vicinity of the Brink’s offices on the evening of January 17, 1950, the FBI learned that a 1949 green Ford stake-body truck with a canvas top had been parked near the Prince Street door of Brink’s at approximately the time of the robbery. From the size of the loot and the number of men involved, it was logical that the gang might have used a truck. This lead was pursued intensively.

On March 4, 1950, pieces of an identical truck were found at a dump in Stoughton, Massachusetts. An acetylene torch had been used to cut up the truck, and it appeared that a sledge hammer also had been used to smash many of the heavy parts, such as the motor. The truck pieces were concealed in fiber bags when found. Had the ground not been frozen, the person or persons who abandoned the bags probably would have attempted to bury them.

The truck found at the dump had been reported stolen by a Ford dealer near Fenway Park in Boston on November 3, 1949. All efforts to identify the persons responsible for the theft and the persons who had cut up the truck were unsuccessful.

Burlap money bags recovered in a Boston junk yard from the robbery

The fiber bags used to conceal the pieces were identified as having been used as containers for beef bones shipped from South America to a gelatin manufacturing company in Massachusetts. Thorough inquiries were made concerning the disposition of the bags after their receipt by the Massachusetts firm. This phase of the investigation was pursued exhaustively. It ultimately proved unproductive.

Nonetheless, the finding of the truck parts at Stoughton, Massachusetts, was to prove a valuable “break” in the investigation. Two of the participants in the Brink’s robbery lived in the Stoughton area. After the truck parts were found, additional suspicion was attached to these men.

Field of Suspects Narrows

As the investigation developed and thousands of leads were followed to dead ends, the broad field of possible suspects gradually began to narrow.

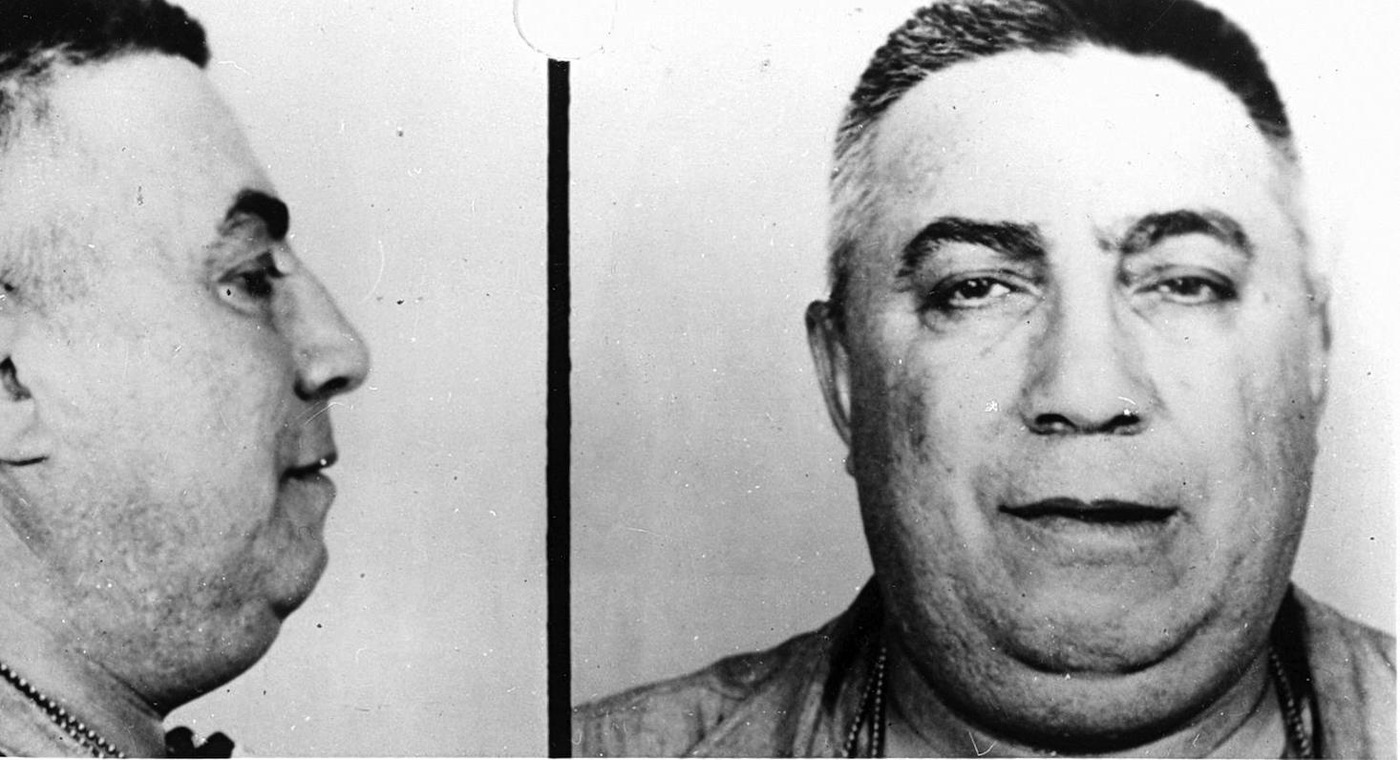

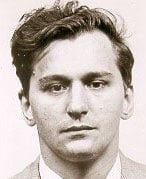

Among the early suspects was Anthony Pino, an alien who had been a principal suspect in numerous major robberies and burglaries in Massachusetts. Pino was known in the underworld as an excellent “case man,” and it was said that the “casing” of the Brink’s offices bore his “trademark.”

Anthony Pino

Pino had been questioned as to his whereabouts on the evening of January 17, 1950, and he provided a good alibi. The alibi, in fact, was almost too good. Pino had been at his home in the Roxbury Section of Boston until approximately 7:00 p.m.; then he walked to the nearby liquor store of Joseph McGinnis. Subsequently, he engaged in a conversation with McGinnis and a Boston police officer. The officer verified the meeting. The alibi was strong, but not conclusive. The police officer said he had been talking to McGinnis first, and Pino arrived later to join them. The trip from the liquor store in Roxbury to the Brink’s offices could be made in about 15 minutes. Pino could have been at McGinnis’ liquor store shortly after 7:30 p.m. on January 17, 1950, and still have participated in the robbery.

And what of McGinnis himself? Commonly regarded as a dominant figure in the Boston underworld, McGinnis previously had been convicted of robbery and narcotics violations. Underworld sources described him as fully capable of planning and executing the Brink’s robbery. He, too, had left his home shortly before 7:00 p.m. on the night of the robbery and met the Boston police officer soon thereafter. If local hoodlums were involved, it was difficult to believe that McGinnis could be as ignorant of the crime as he claimed.

Neither Pino nor McGinnis was known to be the type of hoodlum who would undertake so potentially dangerous a crime without the best “strong-arm” support available. Two of the prime suspects whose nerve and gun-handling experience suited them for the Brink’s robbery were Joseph James O’Keefe and Stanley Albert Gusciora. O’Keefe and Gusciora reportedly had “worked” together on a number of occasions. Both had served prison sentences, and both were well known to underworld figures on the East Coast. O’Keefe’s reputation for nerve was legend. Reports had been received alleging that he had held up several gamblers in the Boston area and had been involved in “shakedowns” of bookies. Like Gusciora, O’Keefe was known to have associated with Pino prior to the Brink’s robbery.

Both of these “strong-arm” suspects had been questioned by Boston authorities following the robbery. Neither had too convincing an alibi. O’Keefe claimed that he left his hotel room in Boston at approximately 7:00 p.m. on January 17, 1950. Following the robbery, authorities attempted unsuccessfully to locate him at the hotel. His explanation: He had been drinking at a bar in Boston. Gusciora also claimed to have been drinking that evening.

The families of O’Keefe and Gusciora resided in the vicinity of Stoughton, Massachusetts. When the pieces of the 1949 green Ford stake-body truck were found at the dump in Stoughton on March 4, 1950, additional emphasis was placed on the investigations concerning them. Local officers searched their homes, but no evidence linking them with the truck or the robbery was found.

In April 1950, the FBI received information indicating that part of the Brink’s loot was hidden in the home of a relative of O’Keefe in Boston. A federal search warrant was obtained, and the home was searched by agents on April 27, 1950. Several hundred dollars were found hidden in the house but could not be identified as part of the loot.

The First Arrests

On June 2, 1950, O’Keefe and Gusciora left Boston by automobile for the alleged purpose of visiting the grave of Gusciora’s brother in Missouri. Apparently, they had planned a leisurely trip with an abundance of “extracurricular activities.”

On June 12, 1950, they were arrested at Towanda, Pennsylvania, and guns and clothing that were the loot from burglaries at Kane and Coudersport, Pennsylvania, were found in their possession.

Following their arrests, a former bondsman in Boston made frequent trips to Towanda in an unsuccessful effort to secure their release on bail. On September 8, 1950, O’Keefe was sentenced to three years in the Bradford County jail at Towanda and fined $3,000 for violation of the Uniform Firearms Act. Although Gusciora was acquitted of the charges against him in Towanda, he was removed to McKean County, Pennsylvania, to stand trial for burglary, larceny, and receiving stolen goods. On October 11, 1950, Gusciora was sentenced to serve from five to 20 years in the Western Pennsylvania Penitentiary at Pittsburgh.

Even after these convictions, O’Keefe and Gusciora continued to seek their release. Between 1950 and 1954, the underworld occasionally rumbled with rumors that pressure was being exerted upon Boston hoodlums to contribute money for these criminals’ legal fight against the charges in Pennsylvania. The names of Pino, McGinnis, Adolph “Jazz” Maffie, and Henry Baker were frequently mentioned in these rumors, and it was said that they had been with O’Keefe on “the Big Job.”

Despite the lack of evidence and witnesses upon which court proceedings could be based, as the investigation progressed there was little doubt that O’Keefe had been one of the central figures in the Brink’s robbery. Pino also was linked with the robbery, and there was every reason to suspect that O’Keefe felt Pino was turning his back on him now that O’Keefe was in jail.

Both O’Keefe and Gusciora had been interviewed on several occasions concerning the Brink’s robbery, but they had claimed complete ignorance. In the hope that a wide breach might have developed between the two criminals who were in jail in Pennsylvania and the gang members who were enjoying the luxuries of a free life in Massachusetts, FBI agents again visited Gusciora and O’Keefe. Even in their jail cells, however, they showed no respect for law enforcement.

In pursuing the underworld rumors concerning the principal suspects in the Brink’s case, the FBI succeeded in identifying more probable members of the gang. There was Adolph “Jazz” Maffie, one of the hoodlums who allegedly was being “pressured” to contribute money for the legal battle of O’Keefe and Gusciora against Pennsylvania authorities. He had been questioned concerning his whereabouts on January 17, 1950, and he was unable to provide any specific account of where he had been.

Henry Baker, another veteran criminal who was rumored to be “kicking in to the Pennsylvania defense fund,” had spent a number of years of his adult life in prison. He had been released on parole from the Norfolk, Massachusetts, Prison Colony on August 22, 1949—only five months before the robbery. At the Prison Colony, Baker was serving two concurrent terms of four to ten years, imposed in 1944 for “breaking and entering and larceny” and for “possession of burglar tools.” At the time of Baker’s release in 1949, Pino was on hand to drive him back to Boston.

Questioned by Boston police on the day following the robbery, Baker claimed that he had eaten dinner with his family on the evening of January 17, 1950, and then left home at about 7:00 p.m. to walk around the neighborhood for about two hours. Since he claimed to have met no one and to have stopped nowhere during his walk, he actually could have been doing anything on the night of the crime.

Prominent among the other strong suspects was Vincent James Costa, brother-in-law of Pino. Costa was associated with Pino in the operation of a motor terminal and a lottery in Boston. He had been convicted of armed robbery in 1940 and served several months in the Massachusetts State Reformatory and the Norfolk, Massachusetts, Prison Colony. Costa claimed that after working at the motor terminal until approximately 5:00 p.m. on January 17, 1950, he had gone home to eat dinner; then, at approximately 7:00 p.m., he left to return to the terminal and worked until about 9:00 p.m.

The FBI’s analysis of the alibis offered by the suspects showed that the hour of 7:00 p.m. on January 17, 1950, was frequently mentioned. O’Keefe had left his hotel at approximately 7:00 p.m. Pino and Baker separately decided to go out at 7:00 p.m. Costa started back to the motor terminal at about 7:00 p.m. Other principal suspects were not able to provide very convincing accounts of their activities that evening. Since the robbery had taken place between approximately 7:10 and 7:27 p.m., it was quite probable that a gang, as well drilled as the Brink’s robbers obviously were, would have arranged to rendezvous at a specific time. By fixing this time as close as possible to the minute at which the robbery was to begin, the robbers would have alibis to cover their activities up to the final moment.

Grand Jury Hearings

Any doubts that the Brink’s gang had that the FBI was on the right track in its investigation were allayed when the federal grand jury began hearings in Boston on November 25, 1952, concerning this crime.

The FBI’s jurisdiction to investigate this robbery was based upon the fact that cash, checks, postal notes, and United States money orders of the Federal Reserve Bank and the Veterans Administration district office in Boston were included in the loot. After nearly three years of investigation, the government hoped that witnesses or participants who had remained mute for so long a period of time might “find their tongues” before the grand jury. Unfortunately, this proved to be an idle hope.

After completing its hearings on January 9, 1953, the grand jury retired to weigh the evidence. In a report which was released on January 16, 1953, the grand jury disclosed that its members did not feel they possessed complete, positive information as to the identify of the participants in the Brink’s robbery because (1) the participants were effectively disguised; (2) there was a lack of eyewitnesses to the crime itself; and (3) certain witnesses refused to give testimony, and the grand jury was unable to compel them to do so.

Ten of the persons who appeared before this grand jury breathed much more easily when they learned that no indictments had been returned. Three years later, almost to the day, these ten men, together with another criminal, were to be indicted by a state grand jury in Boston for the Brink’s robbery.

Following the federal grand jury hearings, the FBI’s intense investigation continued. The Bureau was convinced that it had identified the actual robbers, but evidence and witnesses had to be found.

Pino’s Deportation Troubles

While O’Keefe and Gusciora lingered in jail in Pennsylvania, Pino encountered difficulties of his own.

Born in Italy in 1907, Pino was a young child when he entered the United States, but he never became a naturalized citizen. Due to his criminal record, the Immigration and Naturalization Service instituted proceedings in 1941 to deport him. This occurred while he was in the state prison at Charlestown, Massachusetts, serving sentences for breaking and entering with intent to commit a felony and for having burglar tools in his possession.

That prison term, together with Pino’s conviction in March 1928 for carnal abuse of a girl, provided the basis for the deportation action. Pino was determined to fight against deportation. In the late summer of 1944, he was released from the state prison and was taken into custody by Immigration authorities. During the preceding year, however, he had filed a petition for pardon in the hope of removing one of the criminal convictions from his record.

In September 1949, Pino’s efforts to evade deportation met with success. He was granted a full pardon by the acting governor of Massachusetts. The pardon meant that his record no longer contained the second conviction; thus, the Immigration and Naturalization Service no longer had grounds to deport him.

On January 10, 1953, following his appearance before the federal grand jury in connection with the Brink’s case, Pino was taken into custody again as a deportable alien. The new proceedings were based upon the fact that Pino had been arrested in December 1948 for a larceny involving less than $100. He received a one-year sentence for this offense; however, on January 30, 1950, the sentence was revoked and the case was “placed on file.”

On January 12, 1953, Pino was released on bail pending a deportation hearing. Again, he was determined to fight, using the argument that his conviction for the 1948 larceny offense was not a basis for deportation. After surrendering himself in December 1953 in compliance with an Immigration and Naturalization Service order, he began an additional battle to win release from custody while his case was being argued. Adding to these problems was the constant pressure being exerted upon Pino by O’Keefe from the county jail in Towanda, Pennsylvania.

In the deportation fight that lasted more than two years, Pino won the final victory. His case had gone to the highest court in the land. On April 11, 1955, the Supreme Court ruled that Pino’s conviction in 1948 for larceny (the sentence that was revoked and the case “placed on file”) had not “attained such finality as to support an order of deportation....” Thus, Pino could not be deported.

During the period in which Pino’s deportation troubles were mounting, O’Keefe completed his sentence at Towanda, Pennsylvania. Released to McKean County, Pennsylvania, authorities early in January 1954 to stand trial for burglary, larceny, and receiving stolen goods, O’Keefe also was confronted with a detainer filed by Massachusetts authorities. The detainer involved O’Keefe’s violation of probation in connection with a conviction in 1945 for carrying concealed weapons.

Before his trial in McKean County, he was released on $17,000 bond. While on bond he returned to Boston; on January 23, 1954, he appeared in the Boston Municipal Court on the probation violation charge. When this case was continued until April 1, 1954, O’Keefe was released on $1,500 bond. During his brief stay in Boston, he was observed to contact other members of the robbery gang. He needed money for his defense against the charges in McKean County, and it was obvious that he had developed a bitter attitude toward a number of his close underworld associates.

Returning to Pennsylvania in February 1954 to stand trial, O’Keefe was found guilty of burglary by the state court in McKean County on March 4, 1954. An appeal was promptly noted, and he was released on $15,000 bond.

O’Keefe immediately returned to Boston to await the results of the appeal. Within two months of his return, another member of the gang suffered a legal setback. “Jazz” Maffie was convicted of federal income tax evasion and began serving a nine-month sentence in the Federal Penitentiary at Danbury, Connecticut, in June 1954.

Hatred and Dissension Increase

Underworld rumors alleged that Maffie and Henry Baker were “high on O’Keefe’s list” because they had “beaten him out of” a large amount of money. If Baker heard these rumors, he did not wait around very long to see whether they were true. Soon after O’Keefe’s return in March 1954, Baker and his wife left Boston on a “vacation.”

O’Keefe paid his “respects” to other members of the Brink’s gang in Boston on several occasions in the spring of 1954, and it was obvious to the agents handling the investigation that he was trying to solicit money. He was so cold and persistent in these dealings with his co-conspirators that the agents hoped he might be attempting to obtain a large sum of money—perhaps his share of the Brink’s loot.

During these weeks, O’Keefe renewed his association with a Boston racketeer who had actively solicited funds for the defense of O’Keefe and Gusciora in 1950. Soon the underworld rang with startling news concerning this pair. It was reported that on May 18, 1954, O’Keefe and his racketeer associate took Vincent Costa to a hotel room and held him for several thousand dollars’ ransom. Allegedly, other members of the Brink’s gang arranged for O’Keefe to be paid a small part of the ransom he demanded, and Costa was released on May 20, 1954.

Special agents subsequently interviewed Costa and his wife, Pino and his wife, the racketeer, and O’Keefe. All denied any knowledge of the alleged incident. Nonetheless, several members of the Brink’s gang were visibly shaken and appeared to be abnormally worried during the latter part of May and early in June 1954.

Two weeks of comparative quiet in the gang members’ lives were shattered on June 5, 1954, when an attempt was made on O’Keefe’s life. The Boston underworld rumbled with reports that an automobile had pulled alongside O’Keefe’s car in Dorchester, Massachusetts, during the early morning hours of June 5. Apparently suspicious, O’Keefe crouched low in the front seat of his car as the would-be assassins fired bullets that pierced the windshield.

A second shooting incident occurred on the morning of June 14, 1954, in Dorchester, Massachusetts, when O’Keefe and his racketeer friend paid a visit to Baker. By this time, Baker was suffering from a bad case of nerves. Allegedly, he pulled a gun on O’Keefe; several shots were exchanged by the two men, but none of the bullets found their mark. Baker fled and the brief meeting adjourned.

A third attempt on O’Keefe’s life was made on June 16, 1954. This incident also took place in Dorchester and involved the firing of more than 30 shots. O’Keefe was wounded in the wrist and chest, but again he managed to escape with his life. Police who arrived to investigate found a large amount of blood, a man’s shattered wrist watch, and a .45 caliber pistol at the scene. Five bullets which had missed their mark were found in a building nearby.

On June 17, 1954, the Boston police arrested Elmer “Trigger” Burke and charged him with possession of a machine gun. Subsequently, this machine gun was identified as having been used in the attempt on O’Keefe’s life. Burke, a professional killer, allegedly had been hired by underworld associates of O’Keefe to assassinate him.

After being wounded on June 16, O’Keefe disappeared. On August 1, 1954, he was arrested at Leicester, Massachusetts, and turned over to the Boston police who held him for violating probation on a gun-carrying charge. O’Keefe was sentenced on August 5, 1954, to serve 27 months in prison. As a protective measure, he was incarcerated in the Hampden County jail at Springfield, Massachusetts, rather than the Suffolk County jail in Boston.

O’Keefe’s racketeer associate, who allegedly had assisted him in holding Costa for ransom and was present during the shooting scrape between O’Keefe and Baker, disappeared on August 3, 1954. The missing racketeer’s automobile was found near his home; however, his whereabouts remain a mystery. Underworld figures in Boston have generally speculated that the racketeer was killed because of his association with O’Keefe.

Other members of the robbery gang also were having their troubles. There was James Ignatius Faherty, an armed robbery specialist whose name had been mentioned in underworld conversations in January 1950, concerning a “score” on which the gang members used binoculars to watch their intended victims count large sums of money. Faherty had been questioned on the night of the robbery. He claimed he had been drinking in various taverns from approximately 5:10 p.m. until 7:45 p.m. Some persons claimed to have seen him. Continuous investigation, however, had linked him with the gang.

In 1936 and 1937, Faherty was convicted of armed robbery violations. He was paroled in the fall of 1944 and remained on parole through March 1954 when “misfortune” befell him. Due to unsatisfactory conduct, drunkenness, refusal to seek employment, and association with known criminals, his parole was revoked, and he was returned to the Massachusetts State Prison. Seven months later, however, he was again paroled.

McGinnis had been arrested at the site of a still in New Hampshire in February 1954. Charged with unlawful possession of liquor distillery equipment and violation of Internal Revenue laws, he had many headaches during the period in which O’Keefe was giving so much trouble to the gang. (McGinnis’ trial in March 1955 on the liquor charge resulted in a sentence to 30 days’ imprisonment and a fine of $1,000. In the fall of 1955, an upper court overruled the conviction on the grounds that the search and seizure of the still were illegal.)

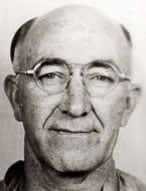

Adolph Maffie, who had been convicted of income tax violation in June 1954, was released from the Federal Corrections Institution at Danbury, Connecticut, on January 30, 1955. Two days before Maffie’s release, another strong suspect died of natural causes. There were recurring rumors that this hoodlum, Joseph Sylvester Banfield (pictured), had been “right down there” on the night of the crime. Banfield had been a close associate of McGinnis for many years. Although he had been known to carry a gun, burglary—rather than armed robbery—was his criminal specialty, and his exceptional driving skill was an invaluable asset during criminal getaways.

Adolph Maffie, who had been convicted of income tax violation in June 1954, was released from the Federal Corrections Institution at Danbury, Connecticut, on January 30, 1955. Two days before Maffie’s release, another strong suspect died of natural causes. There were recurring rumors that this hoodlum, Joseph Sylvester Banfield (pictured), had been “right down there” on the night of the crime. Banfield had been a close associate of McGinnis for many years. Although he had been known to carry a gun, burglary—rather than armed robbery—was his criminal specialty, and his exceptional driving skill was an invaluable asset during criminal getaways.

Like the others, Banfield had been questioned concerning his activities on the night of January 17, 1950. He was not able to provide a specific account, claiming that he became drunk on New Year’s Eve and remained intoxicated through the entire month of January. One of his former girl friends who recalled having seen him on the night of the robbery stated that he definitely was not drunk.

Even Pino, whose deportation troubles then were a heavy burden, was arrested by the Boston police in August 1954. On the afternoon of August 28, 1954, “Trigger” Burke escaped from the Suffolk County jail in Boston, where he was being held on the gun-possession charge arising from the June 16 shooting of O’Keefe. During the regular exercise period, Burke separated himself from the other prisoners and moved toward a heavy steel door leading to the solitary confinement section. As a guard moved to intercept him, Burke started to run. The door opened, and an armed masked man wearing a prison guard-type uniform commanded the guard, “Back up, or I’ll blow your brains out.” Burke and the armed man disappeared through the door and fled in an automobile parked nearby.

An automobile identified as the car used in the escape was located near a Boston hospital, and police officers concealed themselves in the area. On August 29, 1954, the officers’ suspicions were aroused by an automobile that circled the general vicinity of the abandoned car on five occasions. This vehicle was traced through motor vehicle records to Pino. On August 30, he was taken into custody as a suspicious person. Pino admitted having been in the area, claiming that he was looking for a parking place so that he could visit a relative in the hospital. After denying any knowledge of the escape of “Trigger” Burke, Pino was released. (Burke was arrested by FBI agents at Folly Beach, South Carolina, on August 27, 1955, and he returned to New York to face murder charges which were outstanding against him there. He subsequently was convicted and executed.)

O’Keefe Confesses

Despite the fact that substantial amounts of money were being spent by members of the robbery gang during 1954, in defending themselves against legal proceedings alone, the year ended without the location of any bills identifiable as part of the Brink’s loot. In addition, although violent dissension had developed within the gang, there still was no indication that any of the men were ready to “talk.” Based on the available information, however, the FBI felt that O’Keefe’s disgust was reaching the point where it was possible he would turn against his confederates.

During an interview with him in the jail in Springfield, Massachusetts, in October 1954, special agents found that the plight of the missing Boston racketeer was weighing on O’Keefe’s mind. In December 1954, he indicated to the agents that Pino could look for rough treatment if he (O’Keefe) again was released.

From his cell in Springfield, O’Keefe wrote bitter letters to members of the Brink’s gang and persisted in his demands for money. The conviction for burglary in McKean County, Pennsylvania, still hung over his head, and legal fees remained to be paid. During 1955, O’Keefe carefully pondered his position. It appeared to him that he would spend his remaining days in prison while his co-conspirators would have many years to enjoy the luxuries of life. Even if released, he thought, his days were numbered. There had been three attempts on his life in June 1954, and his frustrated assassins undoubtedly were waiting for him to return to Boston.

Evidently resigned to long years in prison or a short life on the outside, O’Keefe grew increasingly bitter toward his old associates. Through long weeks of empty promises of assistance and deliberate stalling by the gang members, he began to realize that his threats were falling on deaf ears. As long as he was in prison, he could do no physical harm to his Boston criminal associates. And the gang felt that the chances of his “talking” were negligible because he would be implicated in the Brink’s robbery along with the others.

Two days after Christmas of 1955, FBI agents paid another visit to O’Keefe. After a period of hostility, he began to display a friendly attitude. Interviewed again on December 28, 1955, he talked somewhat more freely, and it was obvious that the agents were gradually winning his respect and confidence.

At 4:20 p.m. on January 6, 1956, O’Keefe made the final decision. He was through with Pino, Baker, McGinnis, Maffie, and the other Brink’s conspirators who had turned against him. “All right,” he told two FBI agents, “what do you want to know?”

In a series of interviews during the succeeding days, O’Keefe related the full story of the Brink’s robbery. After each interview, FBI agents worked feverishly into the night checking all parts of his story which were subject to verification. Many of the details had previously been obtained during the intense six-year investigation. Other information provided by O’Keefe helped to fill the gaps which still existed.

The following is a brief account of the data which O’Keefe provided the special agents in January 1956:

Although basically the “brain child” of Pino, the Brink’s robbery was the product of the combined thought and criminal experience of men who had known each other for many years. Serious consideration originally had been given to robbing Brink’s in 1947, when Brink’s was located on Federal Street in Boston. At that time, Pino approached O’Keefe and asked if he wanted to be “in on the score.” His close associate, Stanley Gusciora, had previously been recruited, and O’Keefe agreed to take part. The gang at that time included all of the participants in the January 17, 1950, robbery except Henry Baker. Their plan was to enter the Brink’s building and take a truck containing payrolls. Many problems and dangers were involved in such a robbery, and the plans never crystallized.

In December 1948, Brink’s moved from Federal Street to 165 Prince Street in Boston. Almost immediately, the gang began laying new plans. The roofs of buildings on Prince and Snow Hill Streets soon were alive with inconspicuous activity as the gang looked for the most advantageous sites from which to observe what transpired inside Brink’s offices. Binoculars were used in this phase of the “casing” operation.

Before the robbery was carried out, all of the participants were well acquainted with the Brink’s premises. Each of them had surreptitiously entered the premises on several occasions after the employees had left for the day. During their forays inside the building, members of the gang took the lock cylinders from five doors, including the one opening onto Prince Street. While some gang members remained in the building to ensure that no one detected the operation, other members quickly obtained keys to fit the locks. Then the lock cylinders were replaced. (Investigation to substantiate this information resulted in the location of the proprietor of a key shop who recalled making keys for Pino on at least four or five evenings in the fall of 1949. Pino previously had arranged for this man to keep his shop open beyond the normal closing time on nights when Pino requested him to do so. Pino would take the locks to the man’s shop, and keys would be made for them. This man subsequently identified locks from doors which the Brink’s gang had entered as being similar to the locks which Pino had brought him. This man claimed to have no knowledge of Pino’s involvement in the Brink’s robbery.)

Each of the five lock cylinders was taken on a separate occasion. The removal of the lock cylinder from the outside door involved the greatest risk of detection. A passerby might notice that it was missing. Accordingly, another lock cylinder was installed until the original one was returned.

Inside the building, the gang members carefully studied all available information concerning Brink’s schedules and shipments. The “casing” operation was so thorough that the criminals could determine the type of activity taking place in the Brink’s offices by observing the lights inside the building, and they knew the number of personnel on duty at various hours of the day.

A few months prior to the robbery, O’Keefe and Gusciora surreptitiously entered the premises of a protective alarm company in Boston and obtained a copy of the protective plans for the Brink’s building. After these plans were reviewed and found to be unhelpful, O’Keefe and Gusciora returned them in the same manner. McGinnis previously had discussed sending a man to the United States Patent Office in Washington, D.C., to inspect the patents on the protective alarms used in the Brink’s building.

Considerable thought was given to every detail. When the robbers decided that they needed a truck, it was resolved that a new one must be stolen because a used truck might have distinguishing marks and possibly would not be in perfect running condition. Shortly thereafter—during the first week of November—a 1949 green Ford stake-body truck was reported missing by a car dealer in Boston.

During November and December 1949, the approach to the Brink’s building and the flight over the “getaway” route were practiced to perfection. The month preceding January 17, 1950, witnessed approximately a half-dozen approaches to Brink’s. None of these materialized because the gang did not consider the conditions to be favorable.

During these approaches, Costa—equipped with a flashlight for signaling the other men— was stationed on the roof of a tenement building on Prince Street overlooking Brink’s. From this “lookout” post, Costa was in a position to determine better than the men below whether conditions inside the building were favorable to the robbers.

The last “false” approach took place on January 16, 1950—the night before the robbery.

At approximately 7:00 p.m. on January 17, 1950, members of the gang met in the Roxbury section of Boston and entered the rear of the Ford stake-body truck. Banfield, the driver, was alone in the front. In the back were Pino, O’Keefe, Baker, Faherty, Maffie, Gusciora, Michael Vincent Geagan (pictured), and Thomas Francis Richardson.

(Geagan and Richardson, known associates of other members of the gang, were among the early suspects. At the time of the Brink’s robbery, Geagan was on parole, having been released from prison in July 1943, after serving eight years of a lengthy sentence for armed robbery and assault. Richardson had participated with Faherty in an armed robbery in February 1934. Sentenced to serve from five to seven years for this offense, he was released from prison in September 1941. When questioned concerning his activities on the night of January 17, 1950, Richardson claimed that after unsuccessfully looking for work he had several drinks and then returned home. Geagan claimed that he spent the evening at home and did not learn of the Brink’s robbery until the following day. Investigation revealed that Geagan, a laborer, had not gone to work on January 17 or 18, 1950.)

(Geagan and Richardson, known associates of other members of the gang, were among the early suspects. At the time of the Brink’s robbery, Geagan was on parole, having been released from prison in July 1943, after serving eight years of a lengthy sentence for armed robbery and assault. Richardson had participated with Faherty in an armed robbery in February 1934. Sentenced to serve from five to seven years for this offense, he was released from prison in September 1941. When questioned concerning his activities on the night of January 17, 1950, Richardson claimed that after unsuccessfully looking for work he had several drinks and then returned home. Geagan claimed that he spent the evening at home and did not learn of the Brink’s robbery until the following day. Investigation revealed that Geagan, a laborer, had not gone to work on January 17 or 18, 1950.)

During the trip from Roxbury, Pino distributed Navy-type peacoats and chauffeur’s caps to the other seven men in the rear of the truck. Each man also was given a pistol and a Halloween-type mask. Each carried a pair of gloves. O’Keefe wore crepe-soled shoes to muffle his footsteps; the others wore rubbers.

As the truck drove past the Brink’s offices, the robbers noted that the lights were out on the Prince Street side of the building. This was in their favor. After continuing up the street to the end of the playground which adjoined the Brink’s building, the truck stopped. All but Pino and Banfield stepped out and proceeded into the playground to await Costa’s signal. (Costa, who was at his “lookout” post, previously had arrived in a Ford sedan which the gang had stolen from behind the Boston Symphony Hall two days earlier.)

After receiving the “go ahead” signal from Costa, the seven armed men walked to the Prince Street entrance of Brink’s. Using the outside door key they had previously obtained, the men quickly entered and donned their masks. The other keys in their possession enabled them to proceed to the second floor where they took the five Brink’s employees by surprise.

When the employees were securely bound and gagged, the robbers began looting the premises. During this operation, a pair of glasses belonging to one of the employees was unconsciously scooped up with other items and stuffed into a bag of loot. As this bag was being emptied later that evening, the glasses were discovered and destroyed by the gang.

The robbers’ carefully planned routine inside Brink’s was interrupted only when the attendant in the adjoining Brink’s garage sounded the buzzer. Before the robbers could take him prisoner, the garage attendant walked away. Although the attendant did not suspect that the robbery was taking place, this incident caused the criminals to move more swiftly.

Before fleeing with the bags of loot, the seven armed men attempted to open a metal box containing the payroll of the General Electric Company. They had brought no tools with them, however, and they were unsuccessful.

Immediately upon leaving, the gang loaded the loot into the truck that was parked on Prince Street near the door. As the truck sped away with nine members of the gang—and Costa departed in the stolen Ford sedan—the Brink’s employees worked themselves free and reported the crime.

Banfield drove the truck to the house of Maffie’s parents in Roxbury. The loot was quickly unloaded, and Banfield sped away to hide the truck. (Geagan, who was on parole at the time, left the truck before it arrived at the home in Roxbury where the loot was unloaded. He was certain he would be considered a strong suspect and wanted to begin establishing an alibi immediately.) While the others stayed at the house to make a quick count of the loot, Pino and Faherty departed.

Approximately one and one-half hours later, Banfield returned with McGinnis. Prior to this time, McGinnis had been at his liquor store. He was not with the gang when the robbery took place.

The gang members who remained at the house of Maffie’s parents soon dispersed to establish alibis for themselves. Before they left, however, approximately $380,000 was placed in a coal hamper and removed by Baker for security reasons. Pino, Richardson, and Costa each took $20,000, and this was noted on a score sheet.

Before removing the remainder of the loot from the house on January 18, 1950, the gang members attempted to identify incriminating items. Extensive efforts were made to detect pencil markings and other notations on the currency that the criminals thought might be traceable to Brink’s. Even fearing the new bills might be linked with the crime, McGinnis suggested a process for “aging” the new money “in a hurry.”

On the night of January 18, 1950, O’Keefe and Gusciora received $100,000 each from the robbery loot. They put the entire $200,000 in the trunk of O’Keefe’s automobile. Subsequently, O’Keefe left his car—and the $200,000—in a garage on Blue Hill Avenue in Boston.

During the period immediately following the Brink’s robbery, “the heat” was on O’Keefe and Gusciora. Thus, when he and Gusciora were taken into custody by state authorities during the latter part of January 1950, O’Keefe got word to McGinnis to recover his car and the $200,000 that it contained.

A few weeks later, O’Keefe retrieved his share of the loot. It was given to him in a suitcase that was transferred to his car from an automobile occupied by McGinnis and Banfield. Later, when he counted the money, he found that the suitcase contained $98,000. He had been “short changed” $2,000.

O’Keefe had no place to keep so large a sum of money. He told the interviewing agents that he trusted Maffie so implicitly that he gave the money to him for safe keeping. Except for $5,000 that he took before placing the loot in Maffie’s care, O’Keefe angrily stated, he was never to see his share of the Brink’s money again. While Maffie claimed that part of the money had been stolen from its hiding place and that the remainder had been spent in financing O’Keefe’s legal defense in Pennsylvania, other gang members accused Maffie of “blowing” the money O’Keefe had entrusted to his care.

O’Keefe was bitter about a number of matters. First, there was the money. Then, there was the fact that so much “dead wood” was included—McGinnis, Banfield, Costa, and Pino were not in the building when the robbery took place. O’Keefe was enraged that the pieces of the stolen Ford truck had been placed on the dump near his home, and he generally regretted having become associated at all with several members of the gang.

Before the robbery was committed, the participants had agreed that if anyone “muffed,” he would be “taken care of.” O’Keefe felt that most of the gang members had “muffed.” Talking to the FBI was his way of “taking care of” them all.

Arrests and Indictments

On January 11, 1956, the United States Attorney at Boston authorized special agents of the FBI to file complaints charging the 11 criminals with (1) conspiracy to commit theft of government property, robbery of government property, and bank robbery by force and violence and by intimidation, (2) committing bank robbery on January 17, 1950, and committing an assault on Brink’s employees during the taking of the money, and (3) conspiracy to receive and conceal money in violation of the Bank Robbery and Theft of Government Property Statutes. In addition, McGinnis was named in two other complaints involving the receiving and concealing of the loot.

Six members of the gang—Baker, Costa, Geagan, Maffie, McGinnis, and Pino—were arrested by FBI agents on January 12, 1956. They were held in lieu of bail which, for each man, amounted to more then $100,000.

Three of the remaining five gang members were previously accounted for, O’Keefe and Gusciora being in prison on other charges and Banfield being dead. Faherty and Richardson fled to avoid apprehension and subsequently were placed on the list of the FBI’s Ten Most Wanted Fugitives list. Their success in evading arrest ended abruptly on May 16, 1956, when FBI agents raided the apartment in which they were hiding in Dorchester, Massachusetts. At the time of their arrest, Faherty and Richardson were rushing for three loaded revolvers that they had left on a chair in the bathroom of the apartment. The hideout also was found to contain more than $5,000 in coins. (The arrests of Faherty and Richardson also resulted in the indictment of another Boston hoodlum as an accessory after the fact).

As a cooperative measure, the information gathered by the FBI in the Brink’s investigation was made available to the District Attorney of Suffolk County, Massachusetts. On January 13, 1956, the Suffolk County grand jury returned indictments against the 11 members of the Brink’s gang. O’Keefe was the principal witness to appear before the state grand jurors.

Part of the Loot Recovered

Despite the arrests and indictments in January 1956, more than $2,775,000, including $1,218,211.29 in cash, was still missing. O’Keefe did not know where the gang members had hidden their shares of the loot—or where they had disposed of the money if, in fact, they had disposed of their shares. The other gang members would not talk.

Early in June 1956, however, an unexpected “break” developed. At approximately 7:30 p.m. on June 3, 1956, an officer of the Baltimore, Maryland, Police Department was approached by the operator of an amusement arcade. “I think a fellow just passed a counterfeit $10.00 bill on me,” he told the officer.

In examining the bill, a Federal Reserve note, the officer observed that it was in musty condition. The amusement arcade operator told the officer that he had followed the man who passed this $10.00 bill to a nearby tavern. This man, subsequently identified as a small-time Boston underworld figure, was located and questioned. While the officer and amusement arcade operator were talking to him, the hoodlum reached into his pocket, quickly withdrew his hand again and covered his hand with a raincoat he was carrying. Two other Baltimore police officers who were walking along the street nearby noted this maneuver. One of these officers quickly grabbed the criminal’s hand, and a large roll of money fell from it.

The hoodlum was taken to police headquarters where a search of his person disclosed he was carrying more than $1,000, including $860 in musty, worn bills. A Secret Service agent, who had been summoned by the Baltimore officers, arrived while the criminal was being questioned at the police headquarters, and after examining the money found in the bill changer’s possession, he certified that it was not counterfeit.

This underworld character told the officers that he had found this money. He claimed there was a large roll of bills in his hotel room—and that he had found that money, too. The criminal explained that he was in the contracting business in Boston and that in late March or early April 1956, he stumbled upon a plastic bag containing this money while he was working on the foundation of a house.

A search of the hoodlum’s room in a Baltimore hotel (registered to him under an assumed name) resulted in the location of $3,780 that the officers took to police headquarters. At approximately 9:50 p.m., the details of this incident were furnished to the Baltimore Field Office of the FBI. Much of the money taken from the money changer appeared to have been stored a long time. The serial numbers of several of these bills were furnished to the FBI Office in Baltimore. They were checked against serial numbers of bills known to have been included in the Brink’s loot, and it was determined that the Boston criminal possessed part of the money that had been dragged away by the seven masked gunmen on January 17, 1950.

Of the $4,822 found in the small-time criminal’s possession, FBI agents identified $4,635 as money taken by the Brink’s robbers. Interviews with him on June 3 and 4, 1956, disclosed that this 31-year-old hoodlum had a record of arrests and convictions dating back to his teens and that he had been conditionally released from a federal prison camp less than a year before—having served slightly more than two years of a three-year sentence for transporting a falsely made security interstate. At the time of his arrest, there also was a charge of armed robbery outstanding against him in Massachusetts.

During questioning by the FBI, the money changer stated that he was in business as a mason contractor with another man on Tremont Street in Boston. He advised that he and his associate shared office space with an individual known to him only as “Fat John.” According to the Boston hoodlum, on the night of June 1, 1956, “Fat John” asked him to rip a panel from a section of the wall in the office, and when the panel was removed, “Fat John” reached into the opening and removed the cover from a metal container. Inside this container were packages of bills that had been wrapped in plastic and newspapers. “Fat John” announced that each of the packages contained $5,000. “This is good money,” he said, “but you can’t pass it around here in Boston.”

According to the criminal who was arrested in Baltimore, “Fat John” subsequently told him that the money was part of the Brink’s loot and offered him $5,000 if he would “pass” $30,000 of the bills.

The Boston hoodlum told FBI agents in Baltimore that he accepted six of the packages of money from “Fat John.” The following day (June 2, 1956), he left Massachusetts with $4,750 of these bills and began passing them. He arrived in Baltimore on the morning of June 3 and was picked up by the Baltimore Police Department that evening.

The full details of this important development were immediately furnished to the FBI Office in Boston. “Fat John” and the business associate of the man arrested in Baltimore were located and interviewed on the morning of June 4, 1956. Both denied knowledge of the loot that had been recovered. That same afternoon (following the admission that “Fat John” had produced the money and had described it as proceeds from the Brink’s robbery), a search warrant was executed in Boston covering the Tremont Street offices occupied by the three men. The wall partition described by the Boston criminal was located in “Fat John’s” office, and when the partition was removed, a picnic-type cooler was found. This cooler contained more than $57,700, including $51,906 which was identifiable as part of the Brink’s loot.

The discovery of this money in the Tremont Street offices resulted in the arrests of both “Fat John” and the business associate of the criminal who had been arrested in Baltimore. Both men remained mute following their arrests. On June 5 and June 7, the Suffolk County grand jury returned indictments against the three men—charging them with several state offenses involving their possessing money obtained in the Brink’s robbery. (Following pleas of guilty in November 1956, “Fat John” received a two-year sentence, and the other two men were sentenced to serve one year’s imprisonment.)

(After serving his sentence, “Fat John” resumed a life of crime. On June 19, 1958, while out on appeal in connection with a five-year narcotics sentence, he was found shot to death in an automobile that had crashed into a truck in Boston.)

The money inside the cooler which was concealed in the wall of the Tremont Street office was wrapped in plastic and newspaper. Three of the newspapers used to wrap the bills were identified. All had been published in Boston between December 4, 1955, and February 21, 1956. The FBI also succeeded in locating the carpenter who had remodeled the offices where the loot was hidden. His records showed that he had worked on the offices early in April 1956 under instructions of “Fat John.” The loot could not have been hidden behind the wall panel prior to that time.

Because the money in the cooler was in various stages of decomposition, an accurate count proved most difficult to make. Some of the bills were in pieces. Others fell apart as they were handled. Examination by the FBI Laboratory subsequently disclosed that the decomposition, discoloration, and matting together of the bills were due, at least in part, to the fact that all of the bills had been wet. It was positively concluded that the packages of currency had been damaged prior to the time they were wrapped in the pieces of newspaper; and there were indications that the bills previously had been in a canvas container which was buried in ground consisting of sand and ashes. In addition to mold, insect remains also were found on the loot.

Even with the recovery of this money in Baltimore and Boston, more than $1,150,000 of currency taken in the Brink’s robbery remained unaccounted for.

Death of Gusciora

The recovery of part of the loot was a severe blow to the gang members who still awaited trial in Boston. Had any particles of evidence been found in the loot which might directly show that they had handled it? This was a question which preyed heavily upon their minds.

The recovery of part of the loot was a severe blow to the gang members who still awaited trial in Boston. Had any particles of evidence been found in the loot which might directly show that they had handled it? This was a question which preyed heavily upon their minds.

In July 1956, another significant turn of events took place. Stanley Gusciora (pictured left), who had been transferred to Massachusetts from Pennsylvania to stand trial, was placed under medical care due to weakness, dizziness, and vomiting. On the afternoon of July 9, he was visited by a clergyman. During this visit, Gusciora got up from his bed, and, in full view of the clergyman, slipped to the floor, striking his head. Two hours later he was dead. Examination revealed the cause of his death to be a brain tumor and acute cerebral edema.

O’Keefe and Gusciora had been close friends for many years. When O’Keefe admitted his part in the Brink’s robbery to FBI agents in January 1956, he told of his high regard for Gusciora. As a government witness, he reluctantly would have testified against him. Gusciora now had passed beyond the reach of all human authority, and O’Keefe was all the more determined to see that justice would be done.

Trial of Remaining Defendants

With the death of Gusciora, only eight members of the Brink’s gang remained to be tried. (On January 18, 1956, O’Keefe had pleaded guilty to the armed robbery of Brink’s.) The trial of these eight men began on the morning of August 6, 1956, before Judge Feliz Forte in the Suffolk County Courthouse in Boston. The defense immediately filed motions which would delay or prevent the trial. All were denied, and the impaneling of the jury was begun on August 7.

In the succeeding two weeks, nearly 1,200 prospective jurors were eliminated as the defense counsel used their 262 peremptory challenges. Another week passed—and approximately 500 more citizens were considered—before the 14-member jury was assembled.

More than 100 persons took the stand as witnesses for the prosecution and the defense during September 1956. The most important of these, “Specs” O’Keefe, carefully recited the details of the crime, clearly spelling out the role played by each of the eight defendants.

At 10:25 p.m. on October 5, 1956, the jury retired to weigh the evidence. Three and one-half hours later, the verdict had been reached. All were guilty.

The eight men were sentenced by Judge Forte on October 9, 1956. Pino, Costa, Maffie, Geagan, Faherty, Richardson, and Baker received life sentences for robbery, two-year sentences for conspiracy to steal, and sentences of eight years to ten years for breaking and entering at night. McGinnis, who had not been at the scene on the night of the robbery, received a life sentence on each of eight indictments that charged him with being an accessory before the fact in connection with the Brink’s robbery. In addition, McGinnis received other sentences of two years, two and one-half to three years, and eight to ten years.

While action to appeal the convictions was being taken on their behalf, the eight men were removed to the State prison at Walpole, Massachusetts. From their prison cells, they carefully followed the legal maneuvers aimed at gaining them freedom.

The record of the state trial covered more than 5,300 pages. It was used by the defense counsel in preparing a 294-page brief that was presented to the Massachusetts State Supreme Court. After weighing the arguments presented by the attorneys for the eight convicted criminals, the State Supreme Court turned down the appeals on July 1, 1959, in a 35-page decision written by the Chief Justice.

On November 16, 1959, the United States Supreme Court denied a request of the defense counsel for a writ of certiorari.

In the end, the “perfect crime” had a perfect ending—for everyone but the robbers.