A Byte Out of History

The Five-Decade Fugitive Chase

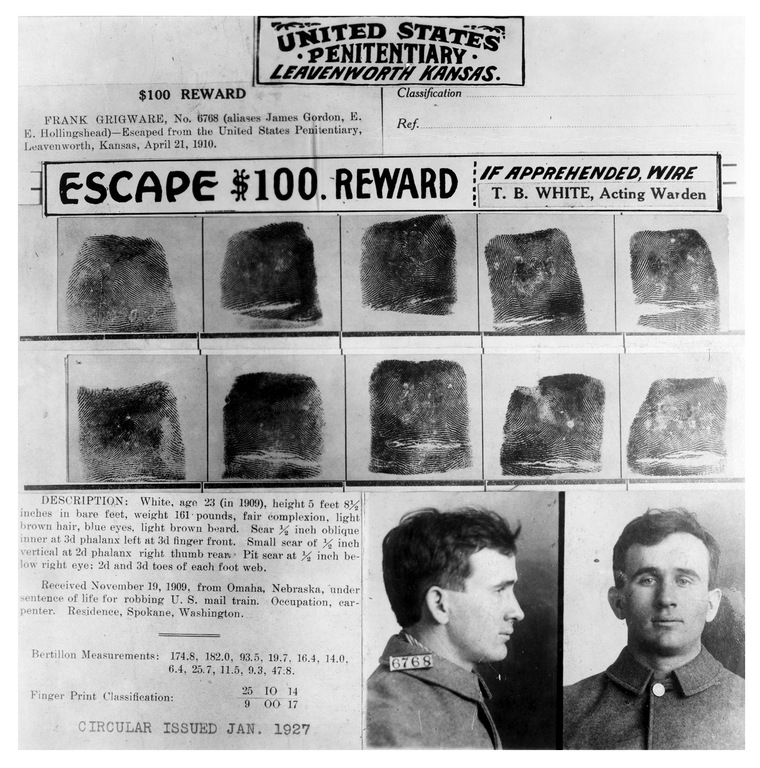

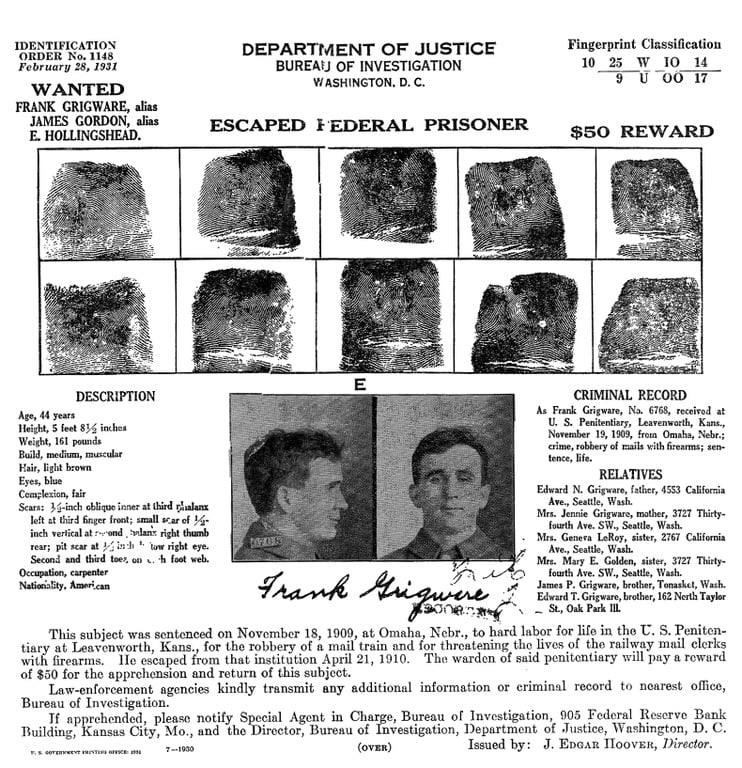

A wanted poster was issued for Frank Grigware after he escaped from federal prison in 1910.

Frank Grigware was serving a life sentence for robbing a mail train in Nebraska when he escaped from the United States Penitentiary in Leavenworth in 1910, and a young Bureau was handed one of its first investigations. It turned out to be one of the longest-running cases in our history.

USP Leavenworth, the nation’s first federal penitentiary, was still under construction in Kansas on that April morning when Grigware and five other convicts made their escape—carving a piece of wood into the shape of a revolver to dupe the guards and busting through the prison gates in a hijacked locomotive used to haul supplies and new inmates into the complex.

Within hours, four of the fugitives were captured. A few days later, the fifth man was found. Only Grigware remained missing. The Bureau of Investigation—the forerunner of today’s FBI—was notified. For years, agents pursued numerous leads across the country and around the world. Grigware was reportedly spotted masquerading as everything from a Catholic priest to a traveling salesman. Catching the now-fabled fugitive became something of a national obsession.

In reality, Grigware had fled to Canada, eventually settling in northern Alberta under the name James Fahey. He began a new life, running a confectionary store, building homes, and becoming active in his church. In 1915, he moved to the small town of Spirit River and was elected mayor the next year. Along the way, he married and had a family.

During those years, the Bureau’s investigation ebbed and flowed as leads dried up and larger events—like World War I—took over. In 1928, the case was reignited, and the following year, the Bureau learned of a credible sighting of Grigware in Edmonton more than a decade earlier. The fugitive’s photo and fingerprints were sent to the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP). By 1933, however, after no success, the Bureau closed its case. Still, a standing wanted notice was kept in place.

Three months later, nearly a quarter century after Grigware’s prison break, the mystery was finally solved. After Grigware was caught poaching in Canada, he was fingerprinted by local authorities. His prints were sent to the RCMP, where an astute clerk matched them to the set sent years before by the Bureau.

The story doesn’t end there, though. The Canadian press suggested that Grigware was innocent of the original charges (which may well have been true) or that he deserved mercy. Many Canadians agreed. They flooded Ottawa and Washington with petitions urging that Grigware be allowed to remain in Canada. In 1934, the U.S. dropped its extradition request.

But could Grigware return to the U.S. to visit his family, his niece asked in 1957? The Department of Justice ruled against this since he had never been officially pardoned, so the FBI kept tabs on Grigware until formally closing the case in 1965. Grigware died in 1977 at the age of 91.

In the end, the pursuit of the former mayor of Spirit River lasted more than a half century. Though Grigware was hardly a dangerous fugitive, the case shows how the keys to the Bureau’s success were already coming into focus in its early years: the tireless quest for justice, the mix of old-fashioned investigative legwork with modern scientific principles like fingerprinting, and the formation of solid partnerships with colleagues across borders. It’s only fitting that one of the FBI’s first cases would end up incorporating so many features of our modern-day investigations.