The FBI Website at 20

Two Decades of Fighting Crime and Terrorism

The FBI.gov homepage as it appeared in June 1997.

In the spring of 1996, a 14-year-old American living in Guatemala happened to visit the less-than-year-old FBI website, apparently out of curiosity.

To his great surprise, the teen immediately recognized a Top Ten fugitive featured on FBI.gov. It was “Uncle Bill”—a family friend and handyman who, ironically, had helped hook up the boy’s computer a few weeks earlier.

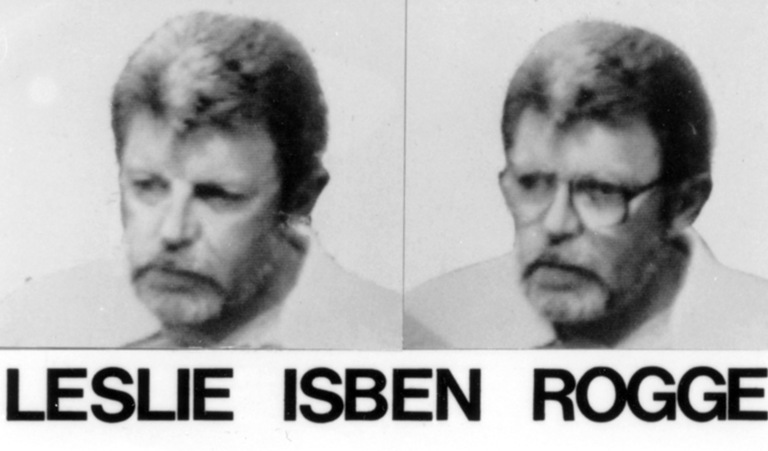

Former Top Ten Fugitive Leslie Ibsen Rogge was the first fugitive captured as a result of appearing on the FBI.gov website, which launched on June 30, 1995.

In reality, Uncle Bill was Leslie Ibsen Rogge, a prolific bank robber who is believed to have pocketed an estimated $2 million from about 30 bank heists across the United States. Rogge landed on the FBI’s Ten Most Wanted Fugitives list in January 1990 and fled to Guatemala about two years later. He had been on the run more than a decade when the teen made his shocking discovery. The ensuing manhunt and media exposure convinced Rogge to surrender to an FBI agent at the U.S. Embassy in Guatemala City on May 18, 1996.

For the Bureau, Rogge’s capture was a milestone. The FBI.gov website was launched on June 30, 1995—20 years ago today—populated with digital versions of the organization’s signature wanted flyers. Less than 11 months later, the site played a direct role in reeling in its first fugitive, a Top Tenner no less. Most likely, the itinerant bank robber represented the first cyberspace capture in the history of U.S. law enforcement.

FBI Web Technology Timeline

- June 30, 1995: FBI.gov website launched

- 1996: First websites for FBI field offices

- May 18, 1996: First fugitive caught as a result of FBI.gov publicity

- January 1998: Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) webpage set up

- September 11, 2001: Electronic tip line established

- February 8, 2002: First Internet-based special agent application

- October 2006: E-mail alerts started

- September 2007: FBI “widgets” launched

- May 2008: First FBI podcasts on iTunes

- November 2008: FBI Twitter site set up

- May 2009: FBI Facebook and YouTube sites established

- October 2010: National Stolen Art File goes online

- April 1, 2011: Electronic FOIA library—The Vault—established

- August 5, 2011: FBI Child ID App announced, Bureau’s first mobile application

- October 15, 2012: FBI Safe Online Surfing website established

- December 2012: Wanted Bank Robbers website launched

- April 2013: Dedicated Boston Marathon tips page set up to accept videos and images

Rogge’s arrest served as something of a proof of concept for the FBI’s use of the Internet as a crime-fighting tool. It has been full steam ahead ever since. FBI.gov now features hundreds of fugitives and missing persons in multiple categories of crime and terrorism. The Bureau dipped its first toe in social media in 2008; today, a steady stream of pictures, podcasts, and videos are broadcast on various channels, including via a specific Most Wanted Twitter feed set up three years ago. In December 2012, the Bureau built the first national electronic repository of its wanted bank robbers on a dedicated website that includes a gallery of nearly 500 searchable suspects and a map that plots robbery locations.

The collective result of all these efforts has been a rising tide of digitally driven captures. Over two decades, a total of 71 fugitives and missing persons have been located as a direct result of the FBI’s web presence, an average of one every three-and-a-half months. Hundreds—if not thousands—more cases involving fugitives and missing persons have been supported by web publicity. There is no longer a need for wanted posters to be tacked to the walls of American post offices when they can be put right at the fingertips of the three billion Internet users around the world.

From its earliest days, the FBI website has sought information from the public on high-profile cases—including the search for the infamous “Unabomber” in the mid-1990s. But it was the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001 that by necessity propelled FBI.gov forward as an operational tool. That day, as the massive investigation got underway, the Bureau quickly stood up an electronic form to gather tips on the attacks from the public. Information came pouring in, and the tip line has been going strong ever since, now expanded to any criminal or national security investigation. This April, it logged its four millionth tip. The submissions have provided vital intelligence in terrorism and espionage cases and prevented a number of shootings and attacks on U.S. soil, including imminent threats to everyone from soldiers to schoolchildren.

Top Ten Tools of FBI.gov

People visit FBI.gov for all kinds of reasons. The following are among the features and tools used most often by the public.

Whether it’s reporting suspicious behavior or providing leads on FBI cases, tips from conscientious citizens help save lives and catch criminals. Learn about the various ways you can submit information, including anonymously (if you wish) through our online form.

Fast Fact: The FBI electronic tip line has received more than four million submissions.

Recognize that face? You can help put wanted fugitives behind bars and reunite missing persons with their families by scrolling through the hundreds of people listed on FBI.gov and contacting us with any information. In some cases, rewards are offered.

Fast Fact: The FBI.gov website has directly aided in the capture of 71 fugitives.

The FBI regularly releases crime statistics of all kinds. From the flagship Crime in the United States to specialized reports on such topics as school violence, you can learn a great deal about the crime challenges facing the country and your communities by studying the data.

Fast Fact: In 2013, an estimated 1.2 million violent crimes were committed in America.

If you’re interested in becoming an FBI special agent, find out what it takes and how to apply. Also check out our many professional support positions. Openings are posted on USA Jobs and published on our FBI Jobs Twitter feed.

Fast Fact: The FBI has more than 35,000 employees, including 13,400 special agents.

Officially called an Identity History Summary Check, for a modest fee the FBI will search its files to see if you have any arrest records and send you the results. There are also several third parties that can request the records on your behalf.

Fast Fact: An Identity History Summary is often referred to as a “rap sheet.”

The FBI investigates thousands of cases every year covering a variety of national security and crime categories. Not all cases are made public, but on FBI.gov you can learn about the types of investigations and read published press releases on active probes.

Fast Fact: The FBI runs 103 multi-agency Joint Terrorism Task Forces nationwide.

There are no X-Files (unless you count the popular “unexplained phenomenon” section), but we’ve posted 6,600 records in our electronic Freedom of Information Act library called “The Vault.” You can browse by topic, search key words, or check the status of your request.

Fast Fact: The Vault received more than 2.5 million visits in 2014.

Scams are everywhere, but these days, they especially seem to fill up our inboxes and lurk in every corner of the Internet. Visit the “Be Crime Smart” webpage to learn about the various kinds of online and offline schemes and how to protect yourself.

Fast Fact: “Swatting” is a scam that involves calling 9-1-1 and faking an emergency.

9. Check Sex Offender Registries

By law, the names and addresses of convicted sex offenders released from prison or off probation are posted online to help keep citizens informed. We have links to all of the searchable systems, including the national database managed by the Department of Justice.

Fast Fact: There are an estimated 800,000 convicted sex offenders in the United States.

The FBI provides many ways to proactively receive its news and information. Our e-mail subscription service—now with 300,000 subscribers—sends updates in 232 categories straight to your inbox. We also have dozens of RSS feeds and 54 social media pages.

Fast Fact: The FBI’s main Twitter page has more than 1.1 million followers.

Increasingly in recent years, FBI.gov also has been integrated into publicity campaigns to reignite cold cases and to aid high profile probes. To support the investigation into the attacks on the U.S. Special Mission in Benghazi in September 2012, for instance, the Bureau set up a special Facebook page in Arabic seeking information from people in Libya and nearby countries.

Along with its investigative value, FBI.gov—as well as the various other specialized Bureau websites that have emerged over the years—supports the needs of many different customers, from the researchers who pore over crime statistics to the police professionals around the world who read the regular FBI Law Enforcement Bulletin. Among other things, these websites enable the public to electronically read Bureau records, explore Bureau careers, and learn about cyber safety.

Over the past 20 years, the FBI’s web presences have become effective crime-fighting and customer service tools, increasingly vital to protecting the public and carrying out the Bureau’s daily work. FBI.gov has been viewed an estimated one billion times since 1995, with traffic to its more than 180,000 pages now averaging around 10 million visits a month. The Bureau’s online presence today also includes 54 social media sites or pages; the agency’s main Facebook and Twitter pages alone have a combined following of 2.2 million people, while its videos on YouTube have nearly 40 million views.

Back in 1996, a single poster on what was then a sparse FBI.gov website forced an international fugitive to turn himself in. Today, thanks to the growing capabilities of the Bureau’s websites, there is less and less room for criminals and terrorists to hide.