Trial By Fire

FBI Training Course Aims to ELEVATE Victim Services

The cellphones started ringing at 6:30 in the morning with a grim message—a mass shooting overnight in the town of Hogan’s Alley. Eleven are confirmed dead, including nine teenagers visiting from a nearby summer camp. More victims are hospitalized. Be at the command post in an hour for a briefing.

So began a harried September morning on the last day of a new, 10-week course the FBI designed to show what it takes to start and operate an effective and sustainable victim services program inside a law enforcement agency. For nine weeks, students from police agencies across the country learned about funding, partnerships, best practices, and case examples in an online class called ELEVATE APB, or Excellence in Law Enforcement-Based Victim Assistance Training and Enrichment Applied Program Building. The 10th week was held at the FBI Training Academy in Quantico, Virginia, where students were paired with experienced mentors and shadowed by FBI Victim Services Division (VSD) personnel as they outlined plans to build or expand their own programs back home.

As the week drew to a close, the busy rhythm of classes, coursework, and networking was shattered by the pre-dawn phone call that a shooting had occurred in the Training Academy’s fictional town. And the students would be evaluated on how well they handled the challenges ahead.

“This is going to be new to a lot of these people,” said Rebecca Elam, a supervisory program manager in the FBI’s VSD, who helped design and implement this first iteration of ELEVATE. “A lot of the students have done operational exercises, but more often than not, those exercises didn't include the victim services response piece.”

By 7:30 a.m., students had crammed into a makeshift command post where they would be briefed by a police commander on what transpired overnight: the number of dead and injured, their locations, the initial emergency response, and the fluid status of the criminal investigation. Afterwards, students and their mentors paired off in turns to face a series of challenges that simulate the very real and unpredictable dynamics victim specialists may face during mass casualty events.

Jimmy Perdue, chief of the North Richland Hills Police Department in Texas, leads an information briefing in the first step of a carefully scripted mass casualty scenario.

The police chief and commanding officers from other police departments attended the final week of ELEVATE APB training to gain a deeper appreciation for the role victim specialists have within law enforcement agencies.

The instructors peppered wide-eyed students with questions that tested their recall from earlier lessons and forced them to put into practice what were just conceptual ideas a few days earlier. “What is your assessment of the situation?” “What is your communication plan?” “What should you be doing next?” In real-life, how well these questions are answered can have lasting impacts on victims and their families.

“If you can assist a victim early on and through the course of an investigation, you can get someone started on a healing path,” said VSD Assistant Director Kathryn Turman.

Only about 15 percent of law enforcement agencies have specialized victim assistance units, according to Department of Justice (DOJ) statistics. More than half of the 3,000 police agencies in a 2013 study have no dedicated personnel at all. Meanwhile, evidence has shown that good victim-oriented programs can result in better witnesses, which can translate into stronger cases and outcomes. Having seen this firsthand, Turman and her VSD team, working with DOJ, spent several years designing ELEVATE to help agencies learn from the victim services template the FBI has developed over nearly two decades.

“The whole idea is to raise that number,” Turman said, referring to police departments with victim services programs.

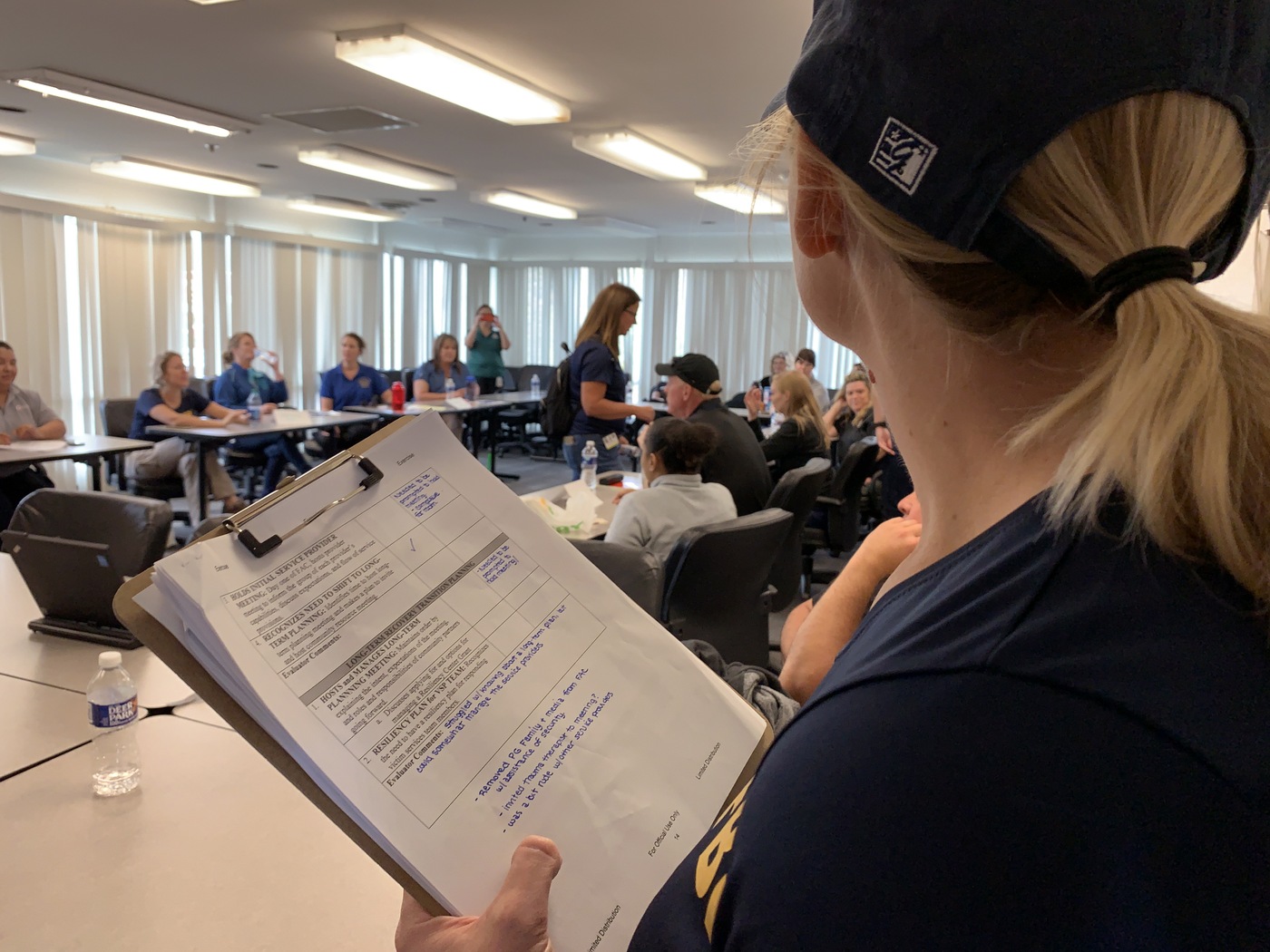

The mass casualty exercise on September 26 was designed to prepare students for the challenges of planning for an incident, providing direct services with partner agencies, and coordinating a long-term plan that meets the needs of victims, their families, and the larger community.

The mass casualty scenario, which included actors playing the roles of victims' family members, capped 10 weeks of training designed to show what it takes to start and operate an effective and sustainable victim services program inside a law enforcement agency.

The first nine weeks of the ELEVATE APB course were conducted online, and the 10th week was held at the FBI Training Academy. In the mock scenario, students responded as victim specialists to a mass shooting, where they had to serve victims and family members, perform death notifications, establish family assistance centers, and generally manage chaotic scenes to support both law enforcement and crime victims.

Having answered their first challenge questions, students advanced to the next hurdle—meeting with victims’ families (played by actors) who don’t know where their loved ones are. Here the students try to calm the unsettled crowd and explain the unfolding process, even as they are assessing how best to serve them. “What is your plan for intake?” an instructor injects, writing notes on a clipboard. “What is the main function of the family resource center?” she asks, referring to the initial gathering place where victims’ families can get official information and assistance.

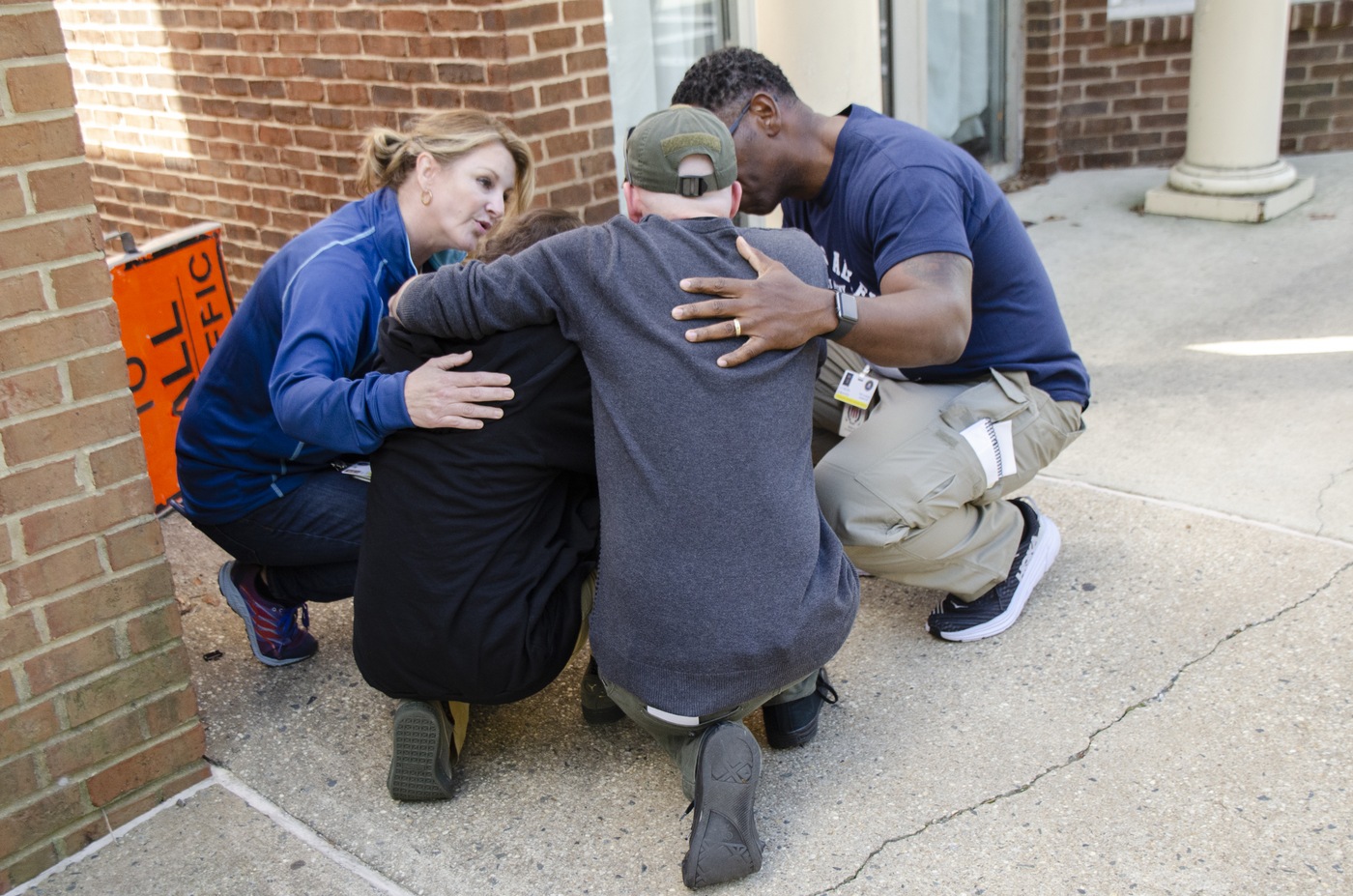

For the rest of the morning, the students (still paired with mentors) faced a growing succession of challenges that tested their intellectual and emotional resolve: consoling devastated families, performing a death notification for a next-of-kin in denial, and establishing and staffing a family assistance center. Along the way, instructors threw wrenches into the mix to see how well students adjusted on the fly.

“That’s what life is like, right? Especially a mass casualty situation,” said Pam Elton, head of VSD’s Victim Program Management Unit, which modeled the ELEVATE course on first-person experiences from more than a dozen VSD deployments to mass casualty incidents. “We wanted to make this as realistic as possible.”

Death notifications are a difficult but necessary role for victim specialists. But done well, a death notification can reduce potential trauma to victims and their families.

"We know too much about how trauma effects a cyclical nature of crime and victimization," said Scott Snow, director of the Crisis Services Division for the Denver Police Department, which has had a victim-services component for more than 30 years. Snow is mentoring an ELEVATE APB student who is trying to establish a victim-centered operation in their department. "If all you do is document, prosecute or attempt to prosecute, and leave," he said, "you’re missing the opportunity to change the familial culture and the dynamics that perpetuate victimization.”

Students and their mentors, as well as visiting police commanders who shadowed their victim service-provider colleagues throughout the week, could not overstate the importance of having a formalized victim assistance program within their departments. The ELEVATE course, they said, reinforced their thinking and provided a time-tested blueprint going forward.

“If you can have someone who’s dedicated, professionally trained, and focused on the victim aspects, that allows investigative priorities to maintain without compromising the ongoing relationship with the victim,” said mentor Scott Snow, director of the Crisis Services Division for the Denver Police Department, which has had a victim services component for more than 30 years. He said it was interesting to hear about the challenges facing his mentee, including how to get a budget for victim services in a department with so many competing law enforcement priorities. That’s one reason command staff were invited to attend—so they can see firsthand the benefits of making victims a top priority in their departments.

“We know too much about how trauma effects a cyclical nature of crime and victimization,” Snow said. “If all you do is document, prosecute or attempt to prosecute, and leave, you’re missing the opportunity to change the familial culture and the dynamics that perpetuate victimization.”

Travis Patten, sheriff of Adams County in Natchez, Mississippi, said bringing victim services under his department a few years ago has significantly impacted the local crime rate and how his community views law enforcement.

“We did a needs assessment based on what the people in the community were telling us they were missing,” said Patten, who wants to grow his department’s program. “We started walking people from point A to point Z of the criminal justice process. We stay in contact with them when it’s not just a service call. We show them that they matter.”

The end of the mass casualty exercise and the 10-week course does not mean the end of the lesson. For the next 12 months, mentors like Snow will continue to offer guidance and feedback for their new partners trying to get their programs off the ground.

“What we’re doing here is what we do every day,” Snow said. “It’s elevated. And it’s larger. But this is what we do. If only 15 percent of law enforcement have dedicated victim services, that leaves millions of crime victims in the country that have no direct or immediate access to victim services. There’s no way around that it’s just the right thing to do—to help people beyond just that original contact.”

The FBI plans to offer the ELEVATE program again in January and then on a regular basis in coming years. The program is funded in part by DOJ’s Crime Victims Fund, which was established through the Victims of Crime Act of 1984, and is financed through penalties paid by convicted federal offenders. ELEVATE is not a big program yet, but it’s a start, VSD Assistant Director Turman said.

“It’s a drop in the bucket,” she said. “But we figured if we start seeding some departments out there with their victim services, then maybe it will grow.”