FBI New Orleans History

Early 1900s

The FBI has had an office in New Orleans since its first days as an organization. One early Bureau history lists Billups Harris as special agent in charge in 1911 and F.C. Pendleton as special agent in charge in 1914.

There were few agents in New Orleans at the time, but their responsibilities were broad. As a seaport, New Orleans handled its share of federal crimes, including not only crimes on the high seas but also Mann Act (anti-prostitution) cases, Neutrality Act violations, immigrant smuggling, and other matters.

America’s involvement in World War I brought new responsibilities—from national security concerns like sabotage to more mundane violations like impersonation of soldiers. In one case, a Bureau report noted, “Our agents made an extensive investigation of the operations of Captain George Hann, with several aliases, who posed as an army officer to cash worthless checks.”

1920s and 1930s

Like other Bureau offices, the New Orleans Division was investigating civil rights issues from its earliest years. One of the first cases came in 1922, when Louisiana Governor John Parker made a formal complaint to the Bureau about the Ku Klux Klan’s power in the state and its illegal activities. Although much of the Klan’s actions were outside of federal jurisdiction, the Bureau was able to secure the arrest of one of its key leaders, Edward Young Clarke, on a federal prostitution charge.

By 1924, the New Orleans Division was an important office in the Bureau. An inspector traveling through its territory noted that it could be expected to handle a wide variety of crimes, including cases arising from “vessels in and out of that place,” Mexican investigations, automobile thefts, and work around Mobile, “from which place the Mississippi territory can be covered and that part of Florida coming under the New Orleans office.”

Special Agent in Charge Eugene B. Sisk

In May 1924, the Bureau came under the leadership of a young J. Edgar Hoover, who quickly began a systematic reform of the organization. Between 1924 and 1930, New Orleans saw six special agents in charge come and go. Such turnover was not uncommon for the Bureau at the time, which developed leaders by introducing them to a wide variety of challenges and locations.

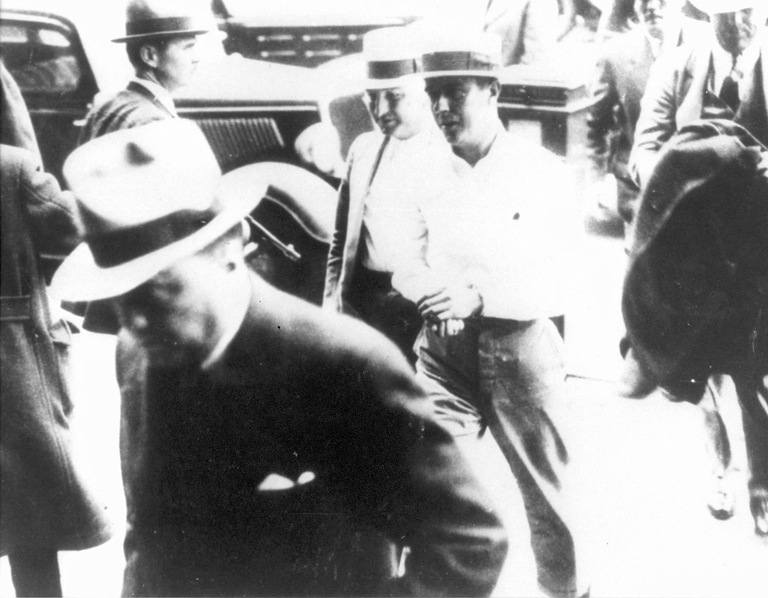

In the 1930s, the New Orleans Division played an important part in helping the nation grapple with the rise of gangsterism. Special Agent Lester Kindell, for example, played a key role in the federal pursuit of Bonnie and Clyde on automobile theft charges. New Orleans agents also located the notorious kidnapper and bank robber Alvin “Creepy” Karpis and backed up Director Hoover when he flew to New Orleans to help with Karpis’ capture.

1940s

FBI Director Hoover (front left) after the arrest of Alvin Karpis

The onset of World War II brought added responsibilities to the office, as homeland security and counterintelligence became the Bureau’s top priorities.

A few months before war even broke out in 1939, the division assigned one agent exclusively to espionage and sabotage cases because of the many military and naval facilities in the New Orleans area. In the coming months, the number of agents working such investigations grew rapidly. Throughout the war, New Orleans agents worked hundreds of sabotage investigations and provided extensive support to armed services facilities and military production companies to help them deter spies and protect their assets.

Throughout the post-war period, the division continued to pursue a wide variety of criminal investigations. In 1946, for instance, six white men kidnapped two African-Americans from a Louisiana jail, beating them severely. One young man was killed; the other, thought to be dead, was left unconscious. The FBI identified all of the killers and developed strong proof of their guilt, but the jury acquitted them based on their defense against “Federal intervention” and “Northern meddling.” It would be many years before stronger federal laws and changing national sentiments began to turn back the tide of such injustices.

1950s and 1960s

The division continued to work a variety of criminal and national security cases in the coming decades. New Orleans agents, for example, took part in the investigating the thieves who stole the Krupp diamond and tracked down a number of army deserters.

On April 28, 1964, New Orleans investigators captured Joseph Francis Bryan, Jr., who had been added to the FBI’s Ten Most Wanted Fugitives list just two weeks earlier. Bryan was wanted for kidnapping and murder when off-duty agents identified his car while he was driving around the city. Bryan was followed and soon arrested. He later pled guilty and was sentenced to life in prison. Two years later, the division arrested another Ten Most Wanted Fugitive, Charles Lorin Gove, who was sought for holding four people hostage during a robbery. Grove was taken without incident in front of a steak house on Bourbon Street in the French Quarter. All told, New Orleans agents have arrested eight Top Ten Fugitives since 1953.

During this time, the FBI lacked the legal tools to go after top mobsters like Carlos Marcello, who had served as the boss of the New Orleans crime family since the late 1940s. The Bureau did investigate Marcello following the assassination of President Kennedy in 1963, and the New Orleans Division managed to get him sent to prison in the late 1960s when he assaulted one of its special agents.

1970s, 1980s, and 1990s

Early New Orleans field office

The FBI’s pressure on Marcello intensified in the coming years, thanks to new racketeering laws that gave the Bureau the ability to take down crime families from the top down. The division’s undercover organized crime investigation known as BRILAB (short for the bribery of labor investigation) led to his conviction on racketeering charges in 1980 and to a wider ranging political corruption investigation that touched the office of Governor Edwin Edwards.

In 1984, New Orleans spearheaded counterterrorism preparations for the World’s Fair that was held in the city. The next year, it joined FBI offices in New York, Newark, and Birmingham in helping to break up a plot to assassinate visiting Indian Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi.

In 1990, the division worked with seven other FBI offices in targeting members of a black separatist cult called the Yahweh Nation, whose members were wanted for a number of serious crimes. The investigation was begun in Miami, where the cult’s headquarters was located and most of the crimes had been committed. In November, New Orleans agents arrested cult leader Hulon Mitchell Jr., who called himself “Yahweh Ben Yahweh.” Immediately after Mitchell was captured, 17 other members of his cult—most of whom were in Miami—were also arrested and charged with numerous murders and with a bombing.

The division launched a major public corruption investigation in 1993 after learning that officers of the New Orleans Police Department were extorting city drug dealers and were engaged in other corrupt activities. Called “Shattered Shield,” the case used an undercover FBI agent pretending to be a drug dealer to gather evidence against the corrupt cops. The end result was the arrest and prosecution of a dozen officers involved in a protection racket and of another officer who had murdered a local citizen. In 1995, New Orleans Police Department Chief Richard Pennington worked with the Department of Justice, the FBI, the U.S. Marine Corps, and the Louisiana State Police to improve ethics education for department leaders.

Another serious criminal case brought to successful conclusion by New Orleans began in Michigan in 1995. In October, Boyd Dean Weekley stole a car in Michigan and then kidnapped and molested two young brothers. He fled across the country, avoiding capture for 10 days before New Orleans agents tracked down the car, arrested him, and quickly found the kidnap victims. Weekley was convicted the next year.

In the late 1990s, the New Orleans Division continued to play a major role in providing security for high visibility special events. In 1997, the office joined with the ATF, the New Orleans Police Department, and other state and local police in working to ensure security at the 1997 Superbowl and the 1997 Bayou Classic held at the New Orleans Superdome. In July 2000, the growing number of counterterrorism cases led the division to create a Joint Terrorism Task Force with other federal, state, and local partner agencies.

Post-9/11

An FBI SWAT Team helps local law enforcement on the streets of New Orleans in the wake of Hurricane Katrina. AP Photo.

Following the events of 9/11, preventing terrorist attacks became the top investigative priority of all Bureau field offices. As a result, the New Orleans Division increased the number of resources devoted to national security matters and worked to integrate intelligence into all of its cases and operations. The division, for instance, created one of the four first Field Intelligence Groups as part of a pilot project, which was later deemed a success and adopted Bureau-wide.

Much changed, however, in the summer of 2005. On August 29, New Orleans and the Gulf Coast were hit by the devastating Hurricane Katrina. The roof of the FBI’s main office in the city was ripped off by the hurricane’s high winds, and the division found itself without a home and access to its records. Even as it scrambled to get back up to speed and make sure its own personnel were safe (thankfully no agents or support staff were harmed, though many lost their homes), the men and women of the New Orleans FBI worked tirelessly to support rescue and security operations throughout the region. Bureau personnel from around the nation were sent to help as well. The division recovered quickly and soon found itself incredibly busy investigating the fraud, corruption, violence, and other crimes that followed in the wake of the storm.

The division, however, continued to keep its eye on national security issues. In February 2008, New Orleans agents arrested a U.S. citizen named Tai Shen Kuo for espionage. Later that year, he pled guilty to spying for the Chinese government, providing classified information about military relations between the U.S. and Taiwan. Several others were also arrested in the course of the investigation and also pled guilty to their role in passing defense information to the Chinese.

After a century of service to the region and the nation, the New Orleans Division looks forward to continuing its national security and criminal responsibilities.