FBI Little Rock History

Early 1900s through 1940s

Early Little Rock Field Office building

Although there was a Bureau office in Little Rock in 1924, it closed for a time, and its territory was handled at various points by Bureau offices in Memphis, Dallas, and Oklahoma City. Rising crime problems in the early 1930s, however, saw the Bureau paying increasingly close attention to the criminal threats in Arkansas. In 1933, for example, two agents and another law enforcement officer found wanted gangster Frank Nash hiding out in Hot Springs, Arkansas, which had a reputation for being a haven for traveling gangsters during this period. The three men arrested Nash and began escorting him back west to prison, but a deadly and now infamous ambush awaited them in Kansas City.

On June 18, 1934, the Bureau reopened the Little Rock Division on the fifth floor of the Rector Office Building at Third and Spring Streets, with Robert L. Shivers serving as the special agent in charge. The new office soon had its hands full with gangster crime throughout the state. The advent of World War II led to a change in Bureau priorities, and the division responded by switching to a focus on national security issues. By 1944, security cases there outnumbered criminal ones by almost two to one.

1950s and 1960s

This trend continued through the early Cold War, but the 1950s brought more challenges. By the mid-1950s, a national movement was growing that challenged segregation. In 1954, the Supreme Court declared segregation in public education illegal. When a number of African-American youth tried to enroll at Little Rock’s Central High School in 1957, a high-stakes confrontation ensued. The Arkansas governor sought to prevent the children from entering the school, but President Eisenhower called out the National Guard to escort and protect them. More than 200 FBI agents were assigned to investigate possible threats against the children, the school, and related targets. The Bureau paid especially close attention to the local Klan members and their plans to see if they crossed the line between protected political activity and criminal violence.

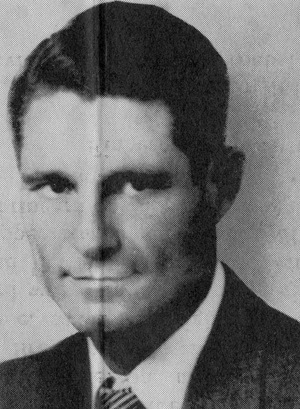

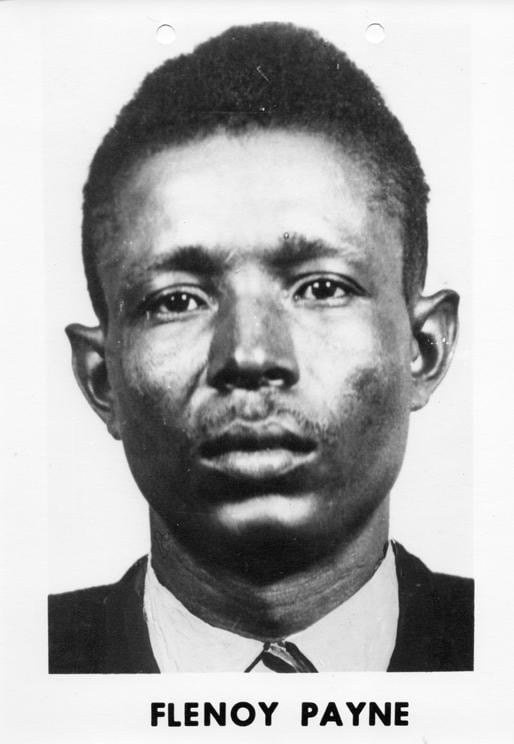

During this tumultuous decade, the division also tracked down criminals like Ten Most Wanted fugitives Charles Edward Ranels, who was captured by Little Rock agents less than three months after he had been named to the list in 1956, and Flenoy Payne.

Charles Edward Ranels

Flenoy Payne

The Klan remained an important focus of the Little Rock Division into the 1960s. Former Special Agent in Charge Herbert Hoxie noted, "We were not interested in legitimate political objectives but if they burned buildings or shot individuals, we’d be on their backs....I think we neutralized the Klan to a great deal in that a lot of people just became inactive, some became informants, and we were just able to keep on top of it."

1970s through 1990s

The division handled kidnappings, bank robberies, and radical bombings through the early 1970s as well.

In the 1980s, organized criminal enterprises like the Bandidos motorcycle gang became targets of FBI operations. The Little Rock Division was a central participant in a nationwide investigation that led to the arrest of more than 80 gang members in 1985. That same year, federal agents surrounded the compound of a white extremist survivalist group known as “The Covenant, The Sword, and the Arm of the Lord.” The group’s leader, James D. Ellison, eventually surrendered to the team—which consisted of Little Rock agents and personnel from several other agencies—on charges of racketeering, arson, and bombing.

In 1988, Little Rock agents broke their biggest spy case, arresting Henry Otto Spade—a former naval radio operator—on charges of espionage and unlawful possession of cryptographic materials.

Post-9/11

Following the events of 9/11, the division joined the entire Bureau in focusing on preventing terrorist attacks. In January 2002, it stood up its first Joint Terrorism Task Force. Three years later, FBI Little Rock was a member of a pilot intelligence effort to improve its awareness of the criminal and security threats in its territory.

In keeping with the FBI’s mission, the Little Rock Division has helped protect local communities and the nation for decades, and it is committed to carrying out this tradition in the years to come.