FBI Detroit History

Early 1900s

Even before the FBI’s official founding, a special agent was assigned to conduct investigations in Detroit for the Department of Justice. By 1911, there was an official field office led by Special Agent in Charge J. Herbert Cole, who served at least through 1914.

In the 1920s, Detroit was a bustling city, and Prohibition was the law of the land. Rum runners from Canada frequented Detroit’s shorelines, and Belle Isle was a common destination for these "entrepreneurs." Although most Prohibition violations fell to the Department of Treasury, Bureau agents in Detroit had their hands full with criminal groups such as the "Purple Gang," which controlled much of this illicit activity and acted ruthlessly in enforcing its will.

1930s and 1940s

In May 1938, John S. Bugas was appointed special agent in charge and oversaw the shift in focus from violent crime to national security. As war loomed in Europe, concern about possible espionage and sabotage attacks on vital American industries like Detroit’s automobile manufacturing plants moved to the forefront. For instance, the Ford Manufacturing Company oversaw construction of the Willow Run B-24 Liberty Bomber, churning out 650 planes per month by the end of 1944. This plant accounted for 70 percent of all B-24 production in the nation during 1945, the last year of World War II. Guarding the secrets of American technology and manufacturing were crucial to the war, and the Detroit Division played an important role in protecting these critical assets.

Early Detroit field office

Investigation of possible subversion was a key concern as well, although sometimes controversial in its application. In February 1940, the division arrested 11 communist-affiliated individuals who sought recruits for the “Abraham Lincoln Brigade,” a crew of Americans who volunteered to fight in the Spanish Civil War. Such recruiting was illegal under U.S. law, but the arrests—and the FBI’s arrest procedures in the case—set off a political battle over whether or not to enforce the Neutrality Act provisions. In the end, the charges were dismissed.

In January 1944, R.A. Guerin replaced Bugas as special agent in charge. A total of 130 special agents and other personnel were assigned to the Detroit Division at this time. That month, the office and the city had their day interrupted by a slight earthquake; no serious damage was incurred, and the Bureau’s work continued. Less than three years later, the division helped its Windsor, Canada neighbors deal with the after-effects of a tornado that killed several people when it touched down across the border.

On November 1, 1945, the Bureau’s Grand Rapids Division became a large resident agency when it was consolidated into the Detroit office. The Detroit Division’s top priority at the time was national security, and the threat of Soviet espionage replaced concerns about Nazi plots.

1950s and 1960s

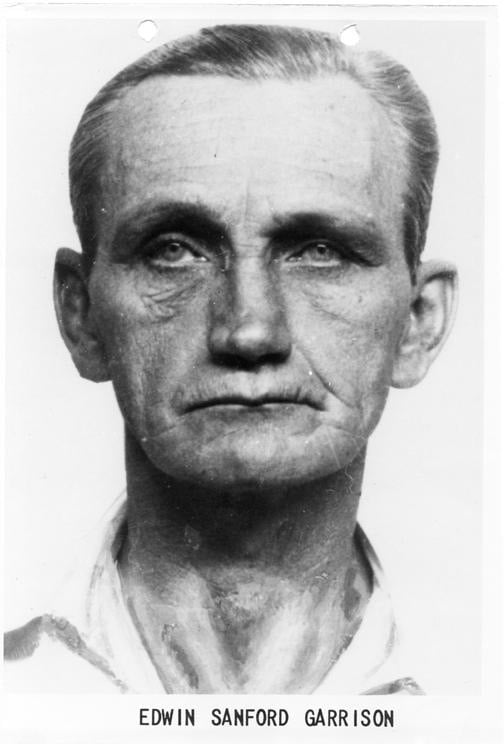

The 1950s brought new challenges, including a growing awareness of the threat from organized crime. Detroit agents tackled their share of dangerous fugitives as well, arresting two Ten Most Wanted Fugitives in 1953. John Raleigh Cook, an armed robber, was captured in October; and Edwin Sanford Garrison, a burglar and prison escapee, was found the next month. The division grew rapidly during this decade. In 1954, it had three resident agencies; within two years, that number had increased to 17.

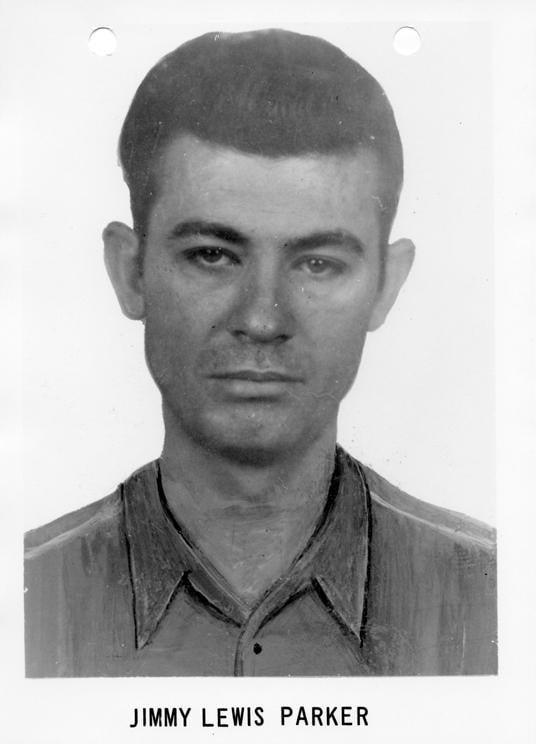

The pursuit of violent fugitives continued in the 1960s. In March 1961, division agents arrested Thomas Viola, a wanted murderer; with the help of a citizen tip. In many cases, the division worked closely with its state and local counterparts in hunting fugitives. On July 24, 1962, for instance, Detroit agents and police officers apprehended Charles Wolfe, Norman Brandt, and Richard Stegeman, three escapees from a Kansas jail. These arrests were made within four hours of the agents learning of the escape—there wasn’t enough time to even consider adding them to the Ten Most Wanted Fugitives list. And later that decade, the division arrested Jimmy Lewis Parker, another Top Tenner.

John Raleigh Cooke

Edwin Sanford Garrison

Thomas Viola

Jimmy Lewis Parker

FBI Detroit also handled a variety of crimes related to Michigan’s manufacturing sector. In 1962, an investigation by the division and the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) led to the conviction of William Frederick Wolff, the president of an Ohio trucking company; and Rolland Boyne, a Teamsters Union official. The two were creating phantom truck rentals to bilk the company.

On January 2, 1964, Detroit agents located and arrested fugitives Robert and Elizabeth Murphy, who were involved in the theft of rare books, coins, and documents from the National Archives in Washington, D.C. Sixteen cartons of stolen items valued in the hundreds of thousands of dollars were recovered as a result of this investigation.

Organized crime was a continuing concern in the 1960s and 1970s. In July 1966, an FBI Detroit investigation enabled Canadian authorities to arrest Anthony Joseph Giacalone and Dominic Peter Corrado, two prominent members of the mob in Detroit, on a variety of racketeering charges. In 1970, the division broke up a major gambling operation run by the mafia. The case targeted an illegal, multi-million-dollar numbers racket. In the end, agents from the Bureau’s offices in Buffalo, Chicago, Cincinnati, Indianapolis, Pittsburgh, and Milwaukee simultaneously raided 58 gambling locations—arresting 66 people and seizing dozens of weapons, tens of thousands of dollars in cash, and gambling records and equipment.

With the increasing radicalization of elements in the anti-war and civil rights movements towards the end of the decade, domestic terrorism became a concern for the division. In 1969, Detroit agents arrested Lawrence Robert Plamondon, John Sinclair, and John Waterhouse Forrest for conspiracy to destroy government property and destruction of government property. Plamondon and Sinclair were members of the White Panther Party; Forrest was a former member of Students for a Democratic Society. The three had bombed a CIA recruiting office in Ann Arbor, Michigan, near the University of Michigan. The division also took a strong interest in the illegal activities of the Black Panther Party, gaining intelligence about a planned attack on Detroit police. The FBI’s quick reporting of this intelligence led to the arrest of eight people and the uncovering of a cache of weapons that were going to be used against the local police.

Jimmy Hoffa in 1965 (Library of Congress)

1970s through 1990s

In 1975, the division’s longest-running organized crime case began when Teamsters President James Hoffa disappeared and was reportedly murdered. Despite a thorough investigation, Hoffa has never been located. In April 1975, Anthony Giardano, head of the St. Louis Syndicate; and two Detroit “captains,” Anthony Zerilli and Michael Pollizzi, were each sentenced to four-year prison terms on gambling charges. A 1970 racketeering law led to even more successes in Michigan and across the United States. The Detroit Division was an important player in many of these cases and a pioneer in developing intelligence about mob activities. In 1980, for instance, FBI Detroit piloted its Organized Crime Information System, an early criminal intelligence database application.

The 1980s saw the division continue to pursue these organized crime investigations even as it dealt with other problems. In 1982, it handled one of the nation’s largest extortion cases involving a threatening letter mailed to the Michigan-based Kellogg Corporation. In Operation Save the Tiger (named for Kellogg’s well-known cereal mascot), Detroit agents quickly identified the extortionists and arrested them before they could carry out their plot to poison Kellogg products unless paid a large ransom. In 1987, the division dealt with another prominent case when it tracked down three people who had robbed a Wolverine Armored Dispatch van of more than $1 million.

Violent drug enterprises were also targeted by the division. In 1988, Detroit agents and Michigan police broke up a major cocaine smuggling operation. That same year, FBI divisions in Detroit and Portland, Oregon joined Michigan State Police, U.S. Customs officers, and IRS personnel in dismantling a major drug and gem smuggling ring.

In the 1990s, the division found itself tackling serious Ponzi schemes, major bank fraud, and various drug-related crimes like money laundering, illegal prescription sales, and health care fraud fraud. In 1990, division agents arrested Gregory Hooper on charges of industrial espionage. Hooper—an employee of General Motors—had stolen company trade secrets that were estimated to be worth $650 million.

During the decade, the division also pursued serious color of law and civil rights violations, as well as organized crime groups. In 1991, a joint FBI/IRS investigation led to the indictment of several active and retired Detroit police officials on charges of embezzlement, obstruction of justice, and income tax violations. The next year, FBI Detroit investigated a serious arson case that targeted an African-American resident of Battle Creek, Michigan. And in 1996, the division’s five-year undercover investigation called GAMTAX culminated in the indictment of 17 members of the Detroit mob—nearly its entire hierarchy—on charges of illegal gambling, loan-sharking, extortion, and acts of violence in support of those crimes. By 1998, Detroit boss Jack Tocco and several of his most important assistants had been convicted.

Post-9/11

Following the events of 9/11, the Detroit Division shifted its focus to countering terrorist threats and strengthening its intelligence capacities. Working closely with the local Muslim communities, it has worked to identify extremist threats and to prevent retaliatory hate crimes against Michigan residents.

With a century of service under its belt, the Detroit Division is committed to using its full range of skills to protect and defend the citizens, businesses, and communities of Michigan in the years ahead.