FBI Dallas History

Early 1900s

Agents have been assigned to Dallas since the earliest days of the Bureau. Special Agent Howard P. Wright was one of the first. In August 1914, he was sent to the Dallas-Fort Worth area to conduct an investigation into rising food prices. World War I had just broken out in Europe, and although America was neutral, concerns about possible price gouging and anti-trust violations were growing stronger. Wright remained in Dallas and was listed in a local directory as the Bureau’s representative the following year. He left the city in July 1916 to head up the Seattle Division.

Special Agent F.M. Spencer succeeded Wright, moving to Dallas permanently in December 1916. He had previously been assigned to our office in San Antonio. Spencer’s priorities in Dallas included investigating violations of the Mann Act, the Sherman Anti-Trust Act, and the Harrison Anti-Narcotic Act. With U.S. entry into World War I in 1917, the office’s national security duties greatly increased. Working with city detectives, Spencer executed a plan to round up draft dodgers. He was also responsible for investigating subversion but appears to have been as willing to exonerate those accused through slander and rumor as to pursue those who may have been real threats to American security. In cooperation with the local Secret Service agent, for example, Spencer issued a public denial of interest in a man accused by rumor of being a German agent. Spencer and his counterpart at the Secret Service said, “We will not undertake to repeat the numerous slanders which we have heard upon the streets, but will say that all of them in toto, are without any foundation in fact.”

Following the end of the war the Bureau’s field office organization was overhauled, but Spencer remained in Dallas. In October 1921, Charles E. Breniman replaced him as Special Agent in Charge when Spencer left to practice law.

Interior of an early Dallas Division office

Bonnie Parker and Clyde Barrow

The Reform Years: 1920s and 1930s

In 1923, Attorney General Harry Daugherty was criticized for failing to sufficiently investigate the many political scandals involving President Warren Harding’s administration. Daugherty was forced to resign in March 1924, and President Calvin Coolidge replaced him with Harlan Fiske Stone. At this time, Dallas Special Agent in Charge Breniman was summoned to testify before the Senate committee investigating the Teapot Dome scandal.

In 1924, Bureau Director William Burns was also dismissed and replaced with J. Edgar Hoover. Hoover initiated a series of reforms to remove politics from the Bureau’s investigative and personnel decisions. Although most of Hoover’s reforms had a clear and strong impact on the Bureau and the Dallas Division, one reform did not succeed. On January 1, 1927, the Bureau attempted to reorganize its agents with accounting backgrounds to better tackle white-collar crime. In addition to managing the Dallas Division, Special Agent in Charge J. E. Gevan was put in charge of a separate regional organization of Bureau accountants. Within a few years, it became clear that this reform was not working, and the agent accountants were reassigned to specific field offices.

At this point, the nation’s economy had descended into depression, and a new group of violent gangsters began terrorizing the West and Midwest with their brazen kidnappings, bank robberies, and various other crimes. The Dallas Division played a key role in the investigation of the kidnapping of oil magnate Charles Urschel by Machine Gun Kelly and his gang.

Dallas agents also led the federal pursuit of Bonnie Parker and Clyde Barrow, a pair of vicious criminals who have achieved posthumous fame. While helping several partners escape from jail in 1932, Clyde Barrow stole an automobile and crossed state lines; in May 1933 a federal complaint was file against Barrow and others. Dallas, because of the location of the initial theft, became the primary office in the case and worked to coordinate the federal chase for Bonnie and Clyde across the Southwest. On May 23, 1934, the criminals were killed in a shootout in northwest Louisiana by local law enforcement. Although not involved in this final confrontation, agents of the Dallas Division had conducted important work in helping to tighten the net around the Barrow gang.

World War II and the Early Cold War: 1940s

As the gangster threat diminished, national security concerns became the Bureau’s top priority. Although the Dallas office was not involved in the late 1930s espionage investigations that concentrated on West Coast Japanese agents and New York Nazi spies, it did begin to increase its national security role as war broke out in Europe in 1939 and intensified its role after the U.S. entered the conflict in December 1941.

Like other offices, Dallas was busy during World War II. Plant security inspections, sabotage cases, and many other war-related matters became regular activities. In 1943 and 1944, agents of the Dallas office assisted in a widespread probe into a Japanese intelligence network centered in Brazil. In the so-called “Rule Case,” the office again played a key role, investigating the activities of German agent Ludwig Bishchoff, a Dallas resident.

During the war, the Dallas Division experienced a tragedy. On July 14, 1943, 27-year-old Special Agent Richard Blackstone Brown was killed and another agent seriously injured in an automobile accident. The pair had been involved in an intensive manhunt for wanted fugitive Albert Earl Walker, and they were following up on a reported sighting of Walker when the accident occurred.

Following the war, America found itself confronting the Soviet Union in the Cold War, and the Dallas Division responded even as it continued its criminal investigations. In one 1946 case, for example, the office worked closely with the FBI Legal Attaché in Brazil to apprehend a fugitive named Irving Goodspeed wanted for murder by Dallas police.

Civil Rights and Assassinations: 1950s and 1960s

Throughout the 1950s, the Dallas Division handled a wide range of issues. In 1963, though, it tackled the most significant investigation in its history and one of the most important cases ever for the Bureau.

Special Agent Richard Blackstone Brown

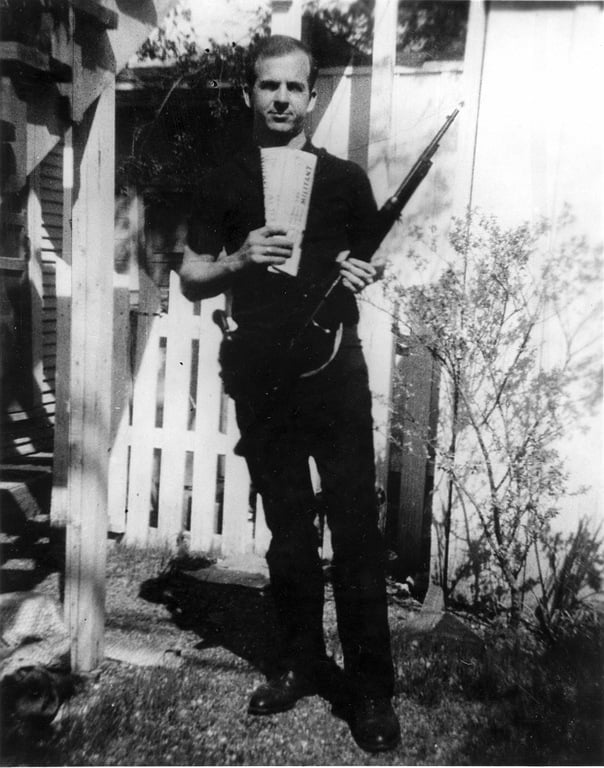

Lee Harvey Oswald

On November 22, Lee Harvey Oswald killed President John F. Kennedy during a parade through the streets of Dallas. At the time there was no federal statute against assassination, but President Johnson ordered the FBI to investigate, and Dallas agents, not surprisingly, played the central role in much of the case. Despite subsequent controversy and the mishandling of a piece of evidence, Dallas did a fine job in recreating Oswald’s activities in Dallas and tracking down available clues related to the assassination.

The 1960s saw the rise of the civil rights movement and the strengthening of laws protecting civil liberties. The Bureau was deeply involved in investigating civil rights cases, and Dallas was no exception. In July 1970, for instance, its agents pursued a white supremacist group that was violently opposed to desegregation and had dynamited several school buses in Longview, Texas. Two people were convicted on civil rights and conspiracy charges.

Watergate and Beyond: 1970s through the 1990s

After Watergate and Bureau counterintelligence abuses came to light, the domestic security work of the FBI as a whole was radically reformed.

Despite more stringent guidelines, the Dallas Division played a key role in several 1970s and 1980s counterterrorism cases. In 1976, for instance, Dallas personnel investigated a series of letter bombs mailed from towns in Texas. And in 1984, the office headed up security preparations for the Republican National Convention held in Dallas.

Counterespionage also remained a priority for the Bureau. In May 1988, Dallas agents arrested Ronald Craig Wolf, a former Air Force pilot, for selling classified information to an FBI undercover officer posing as a Soviet agent. Wolf later pled guilty in federal court and was sentenced to 10 years in prison.

The Savings and Loan crisis of the late 1980s also led to extensive investigative work by the Dallas Division. It opened so many cases into failed Texas banks that three resident agencies received additional agents to help conduct the investigations. In another white-collar crime matter, Dallas personnel teamed up with investigators from the Defense Criminal Services and NASA in 1994 to target NASA contractors suspected of violating laws and regulations governing procurement integrity. Nine individuals and one corporation were eventually charged with federal kickback and bribery offenses.

Domestic terrorism also remained a key concern, and in April 1997, Dallas agents arrested four members of the True Knights of the Ku Klux Klan for conspiracy to commit robbery and to blow up a natural gas processing plant.

Post-9/11

Following the 9/11 attacks, the Dallas Division—like the rest of the Bureau—made preventing terrorist attacks its top priority. The office ramped up its counterterrorism efforts by expanding its Joint Terrorism Task Force and re-engineering its intelligence collection, analysis, and dissemination.

In November 2002, the Dallas Division moved into a new, state-of-the-art facility. Named after J. Gordon Shanklin, the longest serving Dallas Special Agent in Charge, the new building was designed to meet the rigorous security standards needed in a post 9/11 world.

The office continues to tackle a wide variety of crimes—from health care fraud to violent prison gangs…from child pornography pedaled over the Internet to corruption in the halls of government. As the FBI enters its second century, the Dallas Division is ready to tackle new security threats with fidelity, bravery, and integrity.

The Dallas Division Office Locations and Special Agents in Charge, 1914-2008

The Early Years of the Federal Bureau of Investigation1 in Dallas, Texas

The “Old” Dallas Federal Building and Post Office, circa 1930s, from Commerce and S. Ervay looking northeast. The FBI’s first home in Dallas was on the second floor, 1914-1927.

The “Old” Dallas Federal Building and Post Office

In August 1881, the U. S. Treasury Department purchased a parcel of land in downtown Dallas for $11,000. This parcel was roughly the western quarter of the block bounded by Ervay, Main, St. Paul, and Commerce streets, the location today of the old Mercantile Bank building (with the cubical clock tower). There had been previous post offices in Dallas, but this is thought to be the first “federal building” to provide government office space for the United States Post Office and other agencies. In 1914, it would become the first home to the Dallas office of the Department of Justice’s “Bureau of Investigation.”

In 1884, construction began on the central section, the postal facility. The edifice fronted on the east side of Ervay Street and was completed and occupied in 1889. On either side of this first structure, there was vacant land to accommodate coming additions. The Commerce Street addition, with its seven-story clock tower, was completed in 1893, and a matching section was added to the Main Street side in 1904.2

The building served as federal space for 42 years and was vacated in about 1931. It was demolished in 1939 to make way for the Mercantile Bank Building, constructed from 1941 to 1943.3

Later this building would also become a home for the Dallas FBI.

Special Agent Howard P. Wright (1914)

From a review of John F. Worley’s City Directories for Dallas, it appears that H. P. Wright was likely the first Bureau of Investigation special agent assigned to Dallas. He is listed in the 1915 directory under the section on federal officials located in the “ Federal Building, southeast corner Main & Ervay.” Among some 14 other federal offices and officials there appears an entry, “U. S. Department of Justice – Federal Building, H. P. Wright, special agent.”4 Reviews of a number of prior years’ city directories were found to contain no similar entries and no entries for the “Department of Justice.”

The Dallas Morning News archives provide interesting additional information regarding Special Agent Wright. He first appears in an article datelined August 15, 1914 and is further identified as Howard P. Wright from Washington. He was sent to Fort Worth and Dallas to investigate rising food prices after the start of the “European War” (World War I). These inflated prices were possible violations of the Sherman anti-trust law and were an issue of national concern and a priority of Bureau of Investigation agents across the country. The article mentions that Mr. Wright “came to Fort Worth recently and has conducted the investigation of several violations of the Mann Act.”5

A coincidental article, datelined Fort Worth, Texas, August 30, 1914, reported on the weekly meeting of the R. E. Lee Camp, United Confederate Veterans. In the article, recognition is given to Marcus J. Wright of Washington, a collector of Confederate memorabilia and a former Brigadier General of the Confederacy. Marcus Wright is further identified as being the father of Howard P. Wright, Special Agent of the Department of Justice assigned to Fort Worth and Dallas.6

An article datelined Fort Worth, Texas on January 2, 1915, reported that Special Agent Howard P. Wright had just returned from Washington, D.C., where he had spent the holidays at his home. He reported heavy snows in Washington made for “a real White Christmas.” The article also mentioned that Special Agent Wright would be presenting cases to the federal grand jury for the Northern District of Texas the following week.7

On July 29, 1916, The Dallas Morning News reported that Special Agent Howard P. Wright had been transferred and promoted to the agent in charge for the Washington State Division, headquartered in Seattle.8

Special Agent in Charge Will C. Austin

The FBI’s Internet website contains a memorandum prepared on about November 19, 1943, at Los Angeles, California by Special Agent James G. Findlay. This memo was done from Mr. Findlay’s memory, on the occasion of the Bureau’s 35th anniversary, at the request of Assistant Director Louis B. Nichols for the purpose of capturing some of the Bureau’s early history

Agent Findlay had clerked in the U. S. Senate and practiced law in the District of Columbia prior to entering on duty with the Bureau of Investigation in 1911. In his memorandum he provides a brief but interesting history of the genesis of the Bureau of Investigation, as well as identifying many of its early employees. Relevant here is his recollection regarding Dallas. According to Mr. Findlay, in 1911 there were about 16 field offices in operation, with San Antonio being the only one in Texas. These offices had Special Agents in Charge designated to them; however, in many cases they were the only agent assigned to the office.

Mr. Findlay reported that by 1914 five additional offices had been created, Dallas and El Paso among them. Mr. Findlay identifies one Will C. Austin as being the Special Agent in Charge in Dallas in 1914.9

Efforts to further identify and corroborate Mr. Austin as a Dallas agent have been so far unsuccessful by search of The Dallas Morning News archives and the Dallas City directories. It is also noted that in the articles that mention the early Special Agents of Dallas his name does not appear as a predecessor or successor.

Special Agent F. M. Spencer (December 1916)

After Special Agent Wright’s departure to Seattle, Washington, he was followed by Special Agent F. M. Spencer, Department of Justice. The Dallas Morning News reported on December 19, 1916 that Spencer was to move his family from San Antonio, where he had been previously assigned, to his new headquarters in Dallas. From his second floor office in the federal building he was to conduct investigations of all federal matters under the scope of his duties, including violations of the Mann Act, the Sherman anti-trust law, and the Harrison anti-narcotic law.10

The Dallas Morning News archives were found to contain several articles concerning the official duties of Special Agent Spencer that provide a window to the past that bear retelling, if for no other reason than the striking contrast they draw to the present. A few of these excerpted articles are set forth below:

August 17, 1917

“PLAN TO ARREST MEN WHO FAIL TO REPORT

Govt. Special Agent Has List of Thirty ‘Slackers’

Following a day of investigating into the reasons why a number of drafted men failed to appear at the examining boards, the Federal Department of Justice through Special Agent Spencer, in charge of the North Texas District, is ready to institute action in such cases.

Mr. Spencer and the city detective department will round up the alleged slackers. Under the provisions of the United States laws, the slacker automatically becomes a soldier when he fails to appear for examination. When he is arrested for failure to appear he is a soldier and he will be tried on charges of desertion. Under this charge he must appear at courts-martial trial, and the punishment can be fixed at death (emphasis added) for desertion in time of war, if the facts so demand in the minds of those holding the courts-martial trial.

‘I am not of the opinion that such action will be necessary here, said Mr. Spencer, but some drastic action must be taken to convince those registered that Uncle Sam means what he says.’”11

----------------------

October 25, 1917

“RUMORS CONCERNING GEORGE VOLK DENIED

Federal Officers Here Issue Statement Branding Them As Slander

Captain W. H. Forsyth of the United States Secret Service, and F. M. Spencer, Bureau of Investigation Department of Justice, following a conference yesterday morning at the Federal Building, branded as false rumors that have been circulating concerning George A. Volk. They issued a joint statement in which they denied that Mr. Volk had been arrested and jailed or investigated for alleged pro-prussianism.

Their statement follows: ‘We understand that a cruel slander is being circulated generally in Dallas about George A. Volk, to the effect that he is a German spy and has been arrested on that charge.

This is to state that no complaint has ever been made to the Federal Secret Service Office or to the Bureau of Investigation in anywise making any sort of charge against Mr. Volk. In fact, the only mention of the matter that has ever been made to either office has been by curious or interested citizens of Dallas making inquiry as to the report which has uniformly been denied by both departments.

No complaint against Mr. Volk has ever reached either of these offices from any source from Washington or any other source.

There is absolutely no government surveillance over Mr. Volk and never has been and so far as we believe there has never been any cause for any.

We do not know the origin of the slander, nor how it has been so industriously circulated, but we do know that it is absolutely untrue and we take pleasure in publicly stating as much.

Mr. Volk is a native born American citizen, has lived in Dallas ever since he was 19 years of age, during all of which time so far as our acquaintance extends, he has been an industrious, worthy, and useful citizen.

We will not undertake to repeat the numerous slanders which we have heard upon the streets, but will say that all of them in toto, are without any foundation in fact.

We make this statement in justice to a law abiding and loyal citizen of Texas and the United States.’

WILLIAM H. FORSYTH

In Charge U. S. Secret Service

F. M. SPENCER

Bureau of Investigation”12

----------------------

March 24, 1918

“STILL HOLDING “MYSTERY BOOKS”

F. M. Spencer, special investigator for the Department of Justice in Dallas, said yesterday that no disposition had been made of the books entitled, “The Finished Mystery,” which were seized by local agents this week. Mr. Spencer is holding the books in his office, awaiting instructions from Washington as to what shall be done with them.” (“The Finished Mystery” concerns a Jehovah’s Witness prophecy that God will soon destroy the world.)13

----------------------

May 28, 1918

“SPENCER WILL ENFORCE ‘WORK OR FIGHT’ ORDER

F. M. Spencer, Special Investigator for the Department of Justice in Dallas, said yesterday that he had received a copy of the recently enacted “Work or Fight” order by Provost Marshall General Crowder with a letter urging its enforcement in Dallas. He said that he would immediately plan the enforcement of the order and will confer with the chairman of the local exemption boards, the district attorney and officials of the police department.

It is expected that several hundred male clerks, domestic servants, elevator operators, and others engaged in non-essential pursuits will be affected. Already, Mr. Spencer added, his men are picking up many men who failed to return their questionnaires to the exemption boards. These men are being inducted into military service rather than given a term in prison.” 14

Special Agent in Charge Charles E. Breniman (October 1921)

In October 1921, Charles E. Breniman arrived in Dallas as the newly appointed Special Agent in Charge of the Bureau. He replaced F. M. Spencer who had resigned to pursue the practice of law. Mr. Spencer was reported to have been offered a position as a field agent, but declined.

According to an article in The Dallas Morning News, Mr. Breniman, a well-known, 12-year veteran of the Bureau, had previously been the chief of the Bureau’s Pacific Coast Division and had also been in charge of the Southwest Division, headquartered at San Antonio. Mr. Breniman announced that there would be no further personnel changes in the immediate future and field agents J. P. Huddleston, B. C. Baldwin and E. J. Geesan (most likely Geehan)15 of Dallas; John Keith of Fort Worth; and Harry Bishop of Wichita Falls would be retained.16

In July 1922, it was announced that Special Agent Harry Bishop, Wichita Falls, had been placed in temporary charge of the Dallas Division while Charles E. Breniman vacationed in Colorado.17

Special Agent in Charge W. D. Bolling (March 1927)

Dallas National Bank Building

On April 27, 1927, The Dallas Morning News reported:

“Federal Bureau to Move

The United States Department of Justice, Bureau of Investigation will move about May 1 from the second floor of the Federal Building to Rooms 1306-07-08-09-10, Dallas National Bank Building. W. D. Bolling, special agent, is in charge of the office here.” 21

The Beginning of the J. Edgar Hoover Era

During the Warren G. Harding Administration in the early 1920s, Attorney General Harry M. Daugherty fell under suspicion and criticism because of a number of scandals, notably the Teapot Dome naval petroleum reserve debacle and questionable performance as to Prohibition enforcement. Daugherty resigned under pressure in March 1924 and President Calvin Coolidge replaced him with Harlan Fiske Stone. William J. Burns, a friend of Daugherty’s and a former official with the U. S. Secret Service, was appointed in August 1921 to be Director of the Bureau of Investigation. Burns, likewise, submitted his resignation to Stone on May 9, 1924. Interestingly, The Dallas Morning News reported that in early March 1924, Dallas Special Agent in Charge Breniman was summoned to testify before the Senate committee investigating these matters.18

Special Agent in Charge Frank J. Blake (June 1924)

On June 25, 1924, The Dallas Morning News reported:

“New Federal Agent Reaches Dallas

Frank J. Blake of San Antonio reached Dallas Tuesday and will resume his duties within a few days as agent in charge of the Federal Bureau of Investigation of the Department of Justice here. Mr. Blake takes the place vacated some time ago by Charles J. Breniman, who was transferred by request to the Denver district. Mr. Blake formerly was stationed in Fort Worth.”19

The Dallas National Bank Building, 1530 Main Street, was brand new in 1927 when it became the second home for the FBI in Dallas.

Special Agent in Charge Louis De Nette (January 1926)

On January 19, 1926, The Dallas Morning News reported:

“U. S. Department of Justice Now in Charge De Nette

Louis De Nette, formerly of El Paso, has taken charge of the U. S. Department of Justice office here, succeeding Frank Blake, who has been transferred to Kansas City.

E. J. Geehan, special agent of the Department of Justice here has been acting agent in charge for some time while Mr. Blake has been on special duty.

Mr. De Nette had charge of the El Paso office for four years and was in San Antonio before going to El Paso.”

Special Agent in Charge J. A. Gevan (January 1927)

Special Agent Gevan appears as one of Dallas’ Special Agents in Charge in a document titled “Field Office History, DALLAS DIVISION.” This document was compiled by several Dallas employees, notably, former Special Agent Joe A. Pearce.20 Attempts to locate any articles in The Dallas Morning News archives or entries in the Worley City Directories pertaining Mr. Gevan were unsuccessful.

The Dallas National Bank Building, 1530 Main Street, was completed in 1927 and was erected on the site of the old “John Deere” building. In May 2008 it will open as the Joule Hotel after being beautifully restored and refurbished. It is noted that it no longer has a “thirteenth floor.”

United States Post Office & Courthouse. The fourth floor was home for the Dallas FBI during the early 1930s. This view is looking northwest from Bryan Street and St. Paul.

Special Agent in Charge Ralph L. Colvin (August 1929)

On August 9, 1929, Paul E. Reynolds became the second Bureau martyr when he was murdered in El Paso, Texas. A Western Union telegram regarding this killing is an artifact in the Dallas Division museum.22 It is addressed to Special Agent in Charge Colvin at 1308 Dallas National Bank Building, Dallas, Texas.

The 1930 edition of Worley’s Dallas City Directory identifies the federal building as being located at N. Ervay, Bryan, and N. St. Paul streets. Under, “U. S. Department of Justice, Bureau of Investigation,” Ralph H. Colvin is identified as the Special Agent in Charge. In another listing in the Directory, his residence is disclosed as being at 801 W. 10th.23

Special Agent in Charge Frank J. Blake (May 1933)

United States Post Office and Courthouse, 400 N. Ervay

Special Agent in Charge Blake returned to Dallas for a second tour in March 1931.24 Official correspondence dated May 17, 1933, from the historic Bonnie and Clyde file is addressed to him at 420 Post Office Building, Dallas, Texas. These files are on exhibit in the Dallas Division museum.

The United States Post Office and Courthouse, 400 N. Ervay, was completed in 1930 to replace the “Old” Post Office and Federal Building five blocks to the south. It is a five story building in the Italian Renaissance revival style bounded by Ervay, Federal, St. Paul, and Bryan. The building still houses an interesting art deco style post office on the ground floor and the upper floors are currently being converted to residential apartments.25

Special Agent in Charge Edward E. Conroy (May 1938 - Nov. 1940)

The Tower Petroleum Building, 1907 Elm

Frank J. Blake was still Special Agent in Charge in late 1936 or early 1937 when the Bureau moved to its fourth Dallas office. This move took the office to the 12th floor of the new, 22 story, Tower Petroleum Building, 1907 Elm. The building still stands on the northeast corner of Elm and St. Paul, but is vacant and in disrepair.

Edward E. Conroy arrived from New Orleans on May 17, 1938 to relive Special Agent in Charge Blake at this site. Blake, who had been Special Agent in Charge since 1931, was reported to be returning to the Dallas office after a vacation to work under Conroy as a special agent.26 Conroy, described as a decorated World War I Marine Corps captain, left Dallas in November 1940 to head the Newark office of the FBI.27

Special Agent in Charge A. Paul Kitchin (Nov. 1940 – Nov. 1942)

In November 1940, A. Paul Kitchin was transferred from Newark to become the next Special Agent in Charge in Dallas.

Mr. Kitchin served as Special Agent in Charge in Dallas until early November 1942 when he was assigned as Special Agent in Charge in Miami, Florida. He was succeeded by Richard G. Danner. Mr. Danner had been Special Agent in Charge, Miami, so they simply switched places.28 After Special in Charge Danner and his successor, Dean R. Morley, served for about two years each, Mr. Kitchin returned in April 1945 and stayed until his resignation in August 1945.29

Special Agent in Charge Richard G. Danner (Nov. 1942 – Feb. 1944)

Mercantile Bank Building

The Tower Petroleum Building, 1907 Elm, opened in 1931. The FBI was on the 12th floor from 1937 to 1943.

The Mercantile Bank Building, 1704 Main Street. The 13th floor was home to the FBI from July 1943 to June 1953.

The Dallas Morning News articles in early 1943 disclose that the FBI office was relocated to the Mercantile Bank Building located on the southeast corner of S. Ervay and Main Street.30 This was the site of the first federal building in Dallas; the building that first housed the “Bureau of Investigation,” back in 1914. The move was necessary to accommodate a growing federal bureaucracy. After some delay, it appears the office finally moved on about July 1, 1943.

Richard G. Danner reported as the Dallas Special Agent in Charge in early December 1942 and would have supervised the move to the new location. He was 32 years old, a law graduate from Georgetown University, and had been Special Agent in Charge in Atlanta and Miami, before coming to Dallas.31 Mr. Danner was transferred in January 1944 to again be the Special Agent in Charge for Miami.

The Mercantile Bank Building was the only major office building constructed during World War II in the United States. When completed in 1943, it was the tallest building west of the Mississippi, and it remained that way until 1954.

Special Agent in Charge Dean R. Morley (February 1944 – March 1945)

Worley’s 1944-45 Dallas City Directory lists Dean R. Morley as Special Agent in Charge, Federal Bureau of Investigation, U. S. Department of Justice, 1318 Mercantile Bank Building.

The Dallas Morning News reported that Mr. Morley was transferred to Dallas to replace R. G. Danner. Mr. Morley had previously been Special Agent in Charge at Providence, Rhode Island.32 On March 23, 1945, The Dallas Morning News reported that Mr. Morley had been assigned as Special Agent in Charge in Little Rock and that A. Paul Kitchin was returning to again be Special Agent in Charge in Dallas.33

Special Agent in Charge A. Paul Kitchin (April 1945 – August 1945)

Mr. Kitchin returned to Dallas in April 1945, but resigned in August to practice law in North Carolina, his native state. There was also speculation he would pursue political office as others in his family had done. Percy Wylie II, the Special Agent in Charge in Indianapolis, was announced as his replacement.34

Special Agent in Charge Percy Wylie II (August 1945 – September 1947)

The Dallas Morning News noted that Wylie was a 10-year veteran of the Bureau with seven years as a Special Agent in Charge. He was further described as being six feet, three inches tall, weighing 225 pounds, and being part Cherokee Indian. He had attended Vanderbilt University, practiced law, and served in the Oklahoma State Legislature.35

Special Agents in Charge and Bureau Offices in Dallas after World War II

Henry L. McConnell , September 1947

Scott S. Alden , March 1949

Henry O. Hawkins , March 1950

John K. Mumford , September 1951

Santa Fe Federal Building

On June 27, 1953 the Dallas office moved from the 13th floor of the Mercantile Bank Building to the 12th floor of the Santa Fe building, 1114 Commerce. The Santa Fe building, a 20-story structure, was purchased by the federal government in 1948 for needed office space. It was originally built in 1926 to be the headquarters of the Gulf, Colorado, and Santa Fe Railroad.

William A. Murphy , September 1954

Charles E. Weeks , September 1956

Edward L. Boyle , March 1958

Curtis O. Lynum , December 1958

J. Gordon Shanklin , April 1963

The Mercantile Continental Building, 1810 Commerce Street

On April 3, 1964, the Dallas office moved back up Commerce Street to the second floor of the Mercantile Continental Building, 1810 Commerce. The 11-story building had been completed in 1951 and is sometimes referred to as simply the “ Continental Building.” It is readily identified by a large mural in relief above the entrance and the outside terrace set in around the fourth floor. The building is now vacant and in disrepair. Renovation of the building is part of overall plans to restore this central part of downtown Dallas.

Theodore Gunderson , June 1975

James A. Abbott , September 1977

Landmark Center , 1801 N. Lamar

On June 21, 1980, the Dallas office moved to Landmark Center, 1801 N. Lamar in the “West End” of downtown Dallas. This six-story building is one of many red brick structures that are now about 100 years old and comprise a large portion of the West End Historical District. The office initially occupied the 3rd floor, but by 2002 when the FBI moved to its present location, several other floors were leased by the Bureau. This was the headquarters of the Dallas Division for 22 years, longer than any other site to date.

The Santa Fe Building, 1114 Commerce located adjacent to the Earl Cabell Federal Building. The 12th floor was headquarters for FBI Dallas from June 1953 to April 1964.

The Mercantile Continental Bldg., 1810 Commerce. The FBI occupied the second floor from April 1964 to June 1980.

Landmark Center Building, 1801 N. Lamar. The FBI was located in this West End Historic District building for 22 years, from June 1980 to November 2002.

James E. Decker, November 1980

Thomas C. Kelly, October 1981

Bobby R. Gillham, August 1985

Oliver B. “Buck” Revell, May 1991

Danny O. Coulson, September 1991

Danny A. Defenbaugh, January 1998

Guadalupe Gonzalez, May 2002

The J. Gordon Shanklin FBI Building, One Justice Way

On November 4, 2002, the Dallas office moved into its extraordinary and beautiful new facility, built for the FBI and to the rigorous security standards needed for the 21st century. For the first time in Dallas, the FBI had its own complex to handle the myriad of activities underway in a major FBI division headquarters.

The J. Gordon Shanklin Building, One Justice Way, home of the Dallas Office of the FBI since November 2002.

Robert E. Casey, Jr. , June 2006

----------------------

Notes:

1Originally named, “Department of Justice, Bureau of Investigation”

2The Dallas Morning News, “Old Postoffice’s Location Bought for $11,000 in 1881 Said to be Worth Million,” December 2, 1928, page one

3Dallas Historical Society, http://www.dallashistory.org/history/dallas/mercantile_bank.htm.

4Worley’s 1915 City Directory for Dallas, TX, page 892, and other Worley’s City Directories 1912-1917

5The Dallas Morning News, “Investigating Price Advances,” August 16, 1914, Part One, page 2

6The Dallas Morning News, “Veterans Hold Meeting,” August 31, 1914, page 9

7The Dallas Morning News, “Howard P. Wright Returns,” January 3, 1915, Part One, page ten

8The Dallas Morning News, “Federal Official Promoted,” July 29, 1916, page 5

9http://www.fbi.gov/libref/historic/history/historic_doc/findlay.htm

10The Dallas Morning News, “Investigator To Move Here,” December 19, 1916, page 5

11The Dallas Morning News, “The Plan to Arrest Men Who Fail to Report,” August 7, 1917, page14

12The Dallas Morning News, “Rumors Concerning George Volk Denied,” October 25, 1917, page 6

13The Dallas Morning News, “Still Holding ‘Mystery Books’.”, March 24, 1918, Part Four, page 7

14The Dallas Morning News, “Spencer Will Enforce ‘Work or Fight’ Order, May 28, 1918, page 4

15E. J. Geehan became SAC in Dallas for a short time in 1927. The Dallas Morning News published a letter from Mrs. E. J. Geehan in which she defends “Slow Clubs” for young ladies (March 24, 1927) and there are a number of other articles re Geehan from 1922-27.

16The Dallas Morning News, “Federal Agent Is Assuming Duties,” October 21, 1921, page 5

17The Dallas Morning News, “Special Agent Takes Charge,” July 19, 1922, Sec. 2, page22

18The Dallas Morning News, “Daugherty Present At Cabinet Secession,” March 8, 1924, page 1

19The Dallas Morning News, “New Federal Agent Reaches Dallas,” June 25,1924, Sec. 2, page 21

20The Dallas Morning News, “Federal Bureau to Move,” April 27, 1927, Sec. 2, page 13

21Artifact, Federal Bureau of Investigation display, One Justice Way, Dallas, Texas

22Worley’s 1930 City Directory for Dallas TX, pages 31 and 842.

23The Dallas Morning News, “Federal Agent Transferred,” March 19, 1931, Sec. one, page 17

24http://dallaslibrary.org/ctx/photogallery/downtownliving/postoffice.htm

25The Dallas Morning News, “Veteran in Service Takes Over G-Men Headquarters,” May 17, 1938, Sec. two, page one

26The Dallas Morning News, “FBI Chief Here Sent to Newark,” November 16, 1940, Sec one, page 11

27The Dallas Morning News, “FBI Agent Going to Miami,” October 10, 1942, Sec I, page 6

28The Dallas Morning News, “Paul Kitchin, FBI Veteran Resigns Post,” July 14, 1945, Sec II, page one

29The Dallas Morning News, “Income Tax Office Crowds 4 Bureaus Out of Building,” January 10, 1943, Sec II, page 9

30The Dallas Morning News, “FBI Agent Here to Direct Dallas Office,” December 1, 1942, Sec. I, page 3

31The Dallas Morning News, “FBI reassigns Danner to Miami,” Sec. I, page 9

32The Dallas Morning News, “Kitchin Slated to Return Here as G-Man Head,” Sec. I, page 16

33The Dallas Morning News, “Paul Kitchin, FBI Veteran, Resigns Post,” Sec. II, page one

34The Dallas Morning News, “New G-Man Assumes Dallas Office Duties,” Sec. II, page one

Notes:

The photographs of the “Old” Post Office Building, the 1930 Post Office and Courthouse, and the 1927 Dallas National Bank Building were obtained from the Dallas Public Library and printed with permission.

This historical sketch of the nine buildings that housed the Dallas FBI from 1914 to present and the Special Agents in Charge who served in these buildings was compiled by former Special Agent Jesse A. Rogers, 1967 to 1995 (Dallas Division: 1981 to 1995).