FBI Atlanta History

The Early 1900s

From its earliest days as an organization, the Bureau has had a presence in Atlanta. Lewis Josiah Baley was the first Special Agent in Charge (and the longest serving to date). A native of Tennessee, Baley entered the Department of Justice as a special agent in the spring of 1908. He was one of the original members of the Bureau of Investigation when it was formed later that summer and was appointed special agent in charge in Atlanta by 1911. He led that office until 1919, when he was named Chief of the Bureau of Investigation—the number two position at that time. The next year, he returned to lead the Atlanta Division as well as to supervise several other offices in one of the nine divisional headquarters set-up in a short-lived administrative experiment. He retired in 1927.

During his tenure, the Atlanta Division played a significant role in the Bureau’s investigative work. In 1911, for instance, the office was tasked by the Attorney General with investigating allegations of corruption by prison officials in the federal penitentiary in Atlanta. The work of the division continued to grow as the Bureau expanded its anti-prostitution work following the passage of new legislation and then its national security responsibilities as World War I began to impact the United States. The division’s war efforts, in particular, were so appreciated by the community that area businessmen presented Baley with a gold watch for his service after the war ended.

National security remained a key consideration following the war as America faced a series of domestic terrorist attacks in 1919. Although Atlanta was not attacked, hearings regarding anarchist Alexander Berkman and whether he should be deported were held in Atlanta, and the division played an important role in that investigation and related matters.

1920s and 1930s

During 1920s, corruption and fraud in the Atlanta penitentiary became a concern once again. Acting Director J. Edgar Hoover ordered the division to investigate allegations that the warden was managing the prison in a lax manner. Agents quickly uncovered a conspiracy, learning that prison officials and even the chaplain were taking bribes from inmates in return for special treatment. The Bureau’s report on the matter in 1925 led to a series of changes in the prison’s management. The division also pursued white-collar crime in the Bankers Trust Company, a local business.

Despite these successes, the Atlanta Division was closed in May 1930 and responsibility over investigations in Georgia was shifted to a newly created division in Birmingham, Alabama. The change was short lived. In April 1935, the Atlanta office was reopened.

World War II through the 1960s

Like other Bureau offices, Atlanta was busy during World War II. Plant security inspections, sabotage cases, and many other war-related matters became regular activities for its agents.

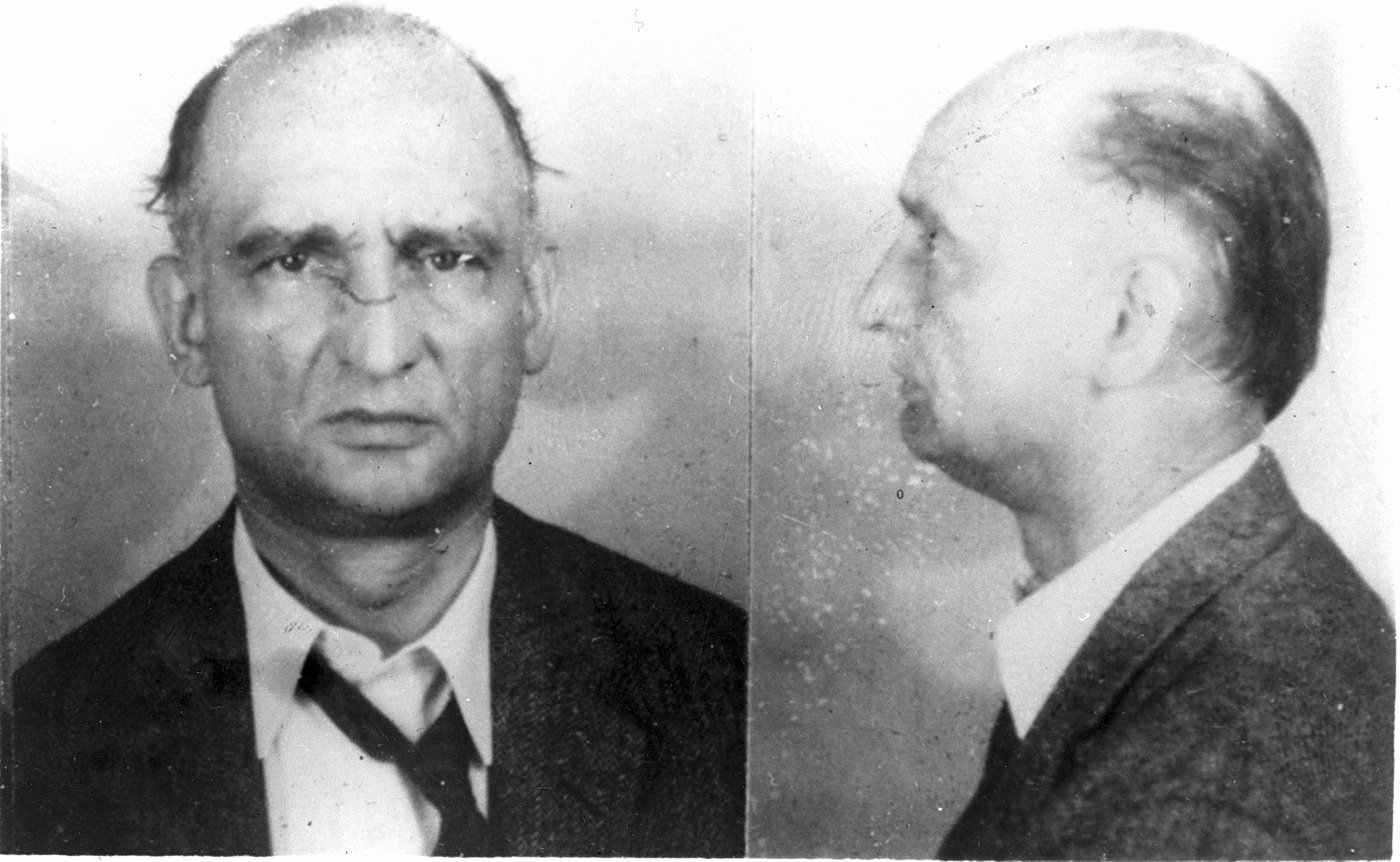

Following the war, America found itself in the midst of a Cold War with the Soviet Union. In one interesting but little known part of a famous case—the so-called Hollow Nickel investigation—the Atlanta Division helped determine that the master spy Rudolf Abel was actually not secretly communicating with the Soviets while in prison. Abel—whose real name was William Fisher—was incarcerated in the Atlanta penitentiary and spent his time pursuing his sketching hobby. Atlanta agents surreptitiously photographed Abel’s artwork and sent it to the FBI Laboratory to ensure that the spy was not using steganography—hiding a message in a graphical image—to communicate with Moscow.

Rudolph Abel

For the Atlanta Division, though, counterintelligence was not always the most pressing issue at the time. It was the violence and hatred directed at African-Americans that led to some of the division’s most important, difficult, and often controversial work.

On July 25, 1946, for instance, two black couples were brutally murdered near the Moore’s Ford Bridge in Monroe, Georgia. Although President Harry Truman immediately dispatched more than two dozen FBI agents to the area, they were met with fear, silence, and cover-up—a situation that appeared all too often in civil rights cases of the day.

In another civil rights case, Ku Klux Klan members shot and killed Lemuel Penn, an African-American WWII veteran and officer in the U.S. Army Reserves, near Athens, Georgia in July 1964. Atlanta agents gathered substantial evidence in the case. Murder charges were filed by state attorneys, but there were no convictions. The crime was also prosecuted in federal court under the new Civil Rights Act of 1964. Of the six men tried, four were acquitted, but two were sent to prison. New laws and strong investigative work were beginning to make a difference. During this time, the division used an extensive network of informers to disrupt Klan activities in Georgia and other southern states. By the early 1970s, the FBI estimated that there were fewer than 2,000 active Klansmen in the nation.

The Atlanta Division also played a major role in the controversial investigation of Dr. Martin Luther King, his advisors, and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference for possible ties to domestic communists and the U.S.S.R. Although predicated on counterintelligence concerns, some subsequent FBI actions during the investigation were criticized. No ties to communists were found.

In December 1968, the Atlanta Division joined agents in Miami in investigating one of the strangest cases in FBI history. A 20-year-old college student named Barbara Jane Mackle, who belonged to a wealthy Florida family, was kidnapped from Decatur, Georgia, where she was recovering from the flu with the help of her mother. Mackle was taken to a wooded area east of Atlanta and essentially buried alive in a sturdy box about 18 inches below ground. The box included vents, food, water, a light, and a fan. The kidnappers—later discovered to be Gary Steven Krist and Ruth Eisemann-Schier—demanded a ransom of $500,000. During the first attempt to hand off the ransom money, police accidentally drove by, and the kidnappers ran off. FBI agents found the kidnappers’ car nearby, complete with their identities and addresses. The second hand off was successful, and the FBI was given general directions to the location of Mackle. Following a massive search, Mackle was found unharmed. Both kidnappers were soon captured and sent to prison.

1970s and 1980s

It was in the wake of the Watergate scandal in the early 1970s that the investigation of Dr. King, the intelligence operation known COINTELPRO, and other actions became public knowledge. The FBI’s domestic security work was radically reformed in light of the ensuing criticism.

In the summer of 1979, the murder of 14-year-old Edward Hope Smith—who lived in a lower income housing project in Southwest Atlanta—marked the start of a string of killings known as the “Atlanta Child Murders.” Soon more children went missing and were found dead. Since all of the victims were African-American, racial tensions in the community began to rise as the death toll mounted; by May 1981, some 29 children, teens, and young adults had been murdered. Meanwhile, the multi-agency task force created to investigate was pursuing every lead; in November 1980, the FBI was asked to assist. A break came when investigators set up a stake-out near a bridge where several bodies had been found; after hearing a splash, authorities followed a car that had slowly sped away and arrested the driver, a man named Wayne Williams. Further investigation—which included meticulous hair and fiber analysis—provided evidence that pointed to Williams as the serial killer. In February 1982, he was convicted of two of the murders. Authorities found enough evidence to suggest that Williams was responsible for at least 22 of the 29 deaths.

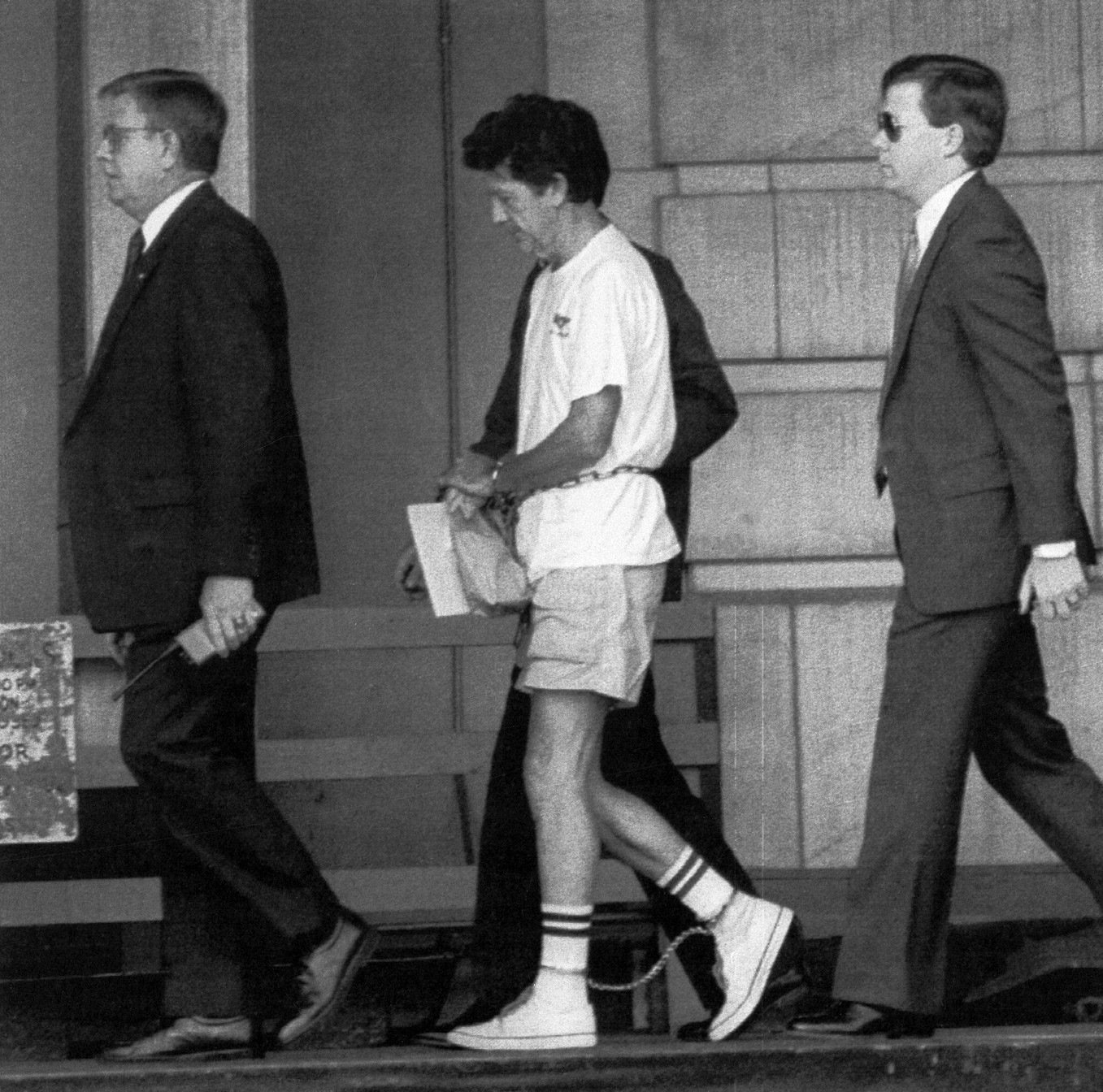

The assassination of a federal appeals judge led to another major Atlanta Division investigation. On December 16, 1989, Judge Robert Vance opened a package, which exploded. He died immediately, and his wife was seriously injured. Other bombs followed. One unexploded bomb was intercepted and examined. The design struck a chord with a colleague in the ATF, who connected it to a man named Walter Leroy Moody. Moody had served time for bomb-making many years earlier and was known to bear a grudge. His ties to the victims suggested that Moody was bent on revenge; an extensive investigation, including a surreptitious recording of Moody talking to himself in jail, provided evidence of his guilt. Moody was later found guilty in both federal and state courts.

Walter Moody (center) is led into a federal courthouse in Macon, Georgia, during a hearing in 1990. Moody was convicted of killing Judge Robert Vance.

1990s

During the summer of 1996, Atlanta hosted the Olympic Games. The Atlanta FBI played a central role in providing security for the event. Despite the precautions, a powerful bomb exploded at Centennial Park in downtown Atlanta. Richard Jewell, a security guard, had noticed a backpack left unattended and had started to move people out of the area. Still, several people were hurt and one died as the bomb exploded. The resulting investigation was swift and exhaustive but failed to identify the person behind the bombing. Jewel—an early suspect—was cleared, but the media frenzy kept his name in the news.

In 1997 and 1998, three more explosions occurred in Atlanta—one at a Georgia woman’s health clinic that provided abortions, another at an Atlanta area nightclub, and a third at another abortion clinic. Secondary explosive devices designed to injure or kill responding law enforcement officials were found at two of the locations (and one police officer was killed). A number of factors linked these bombs to the Centennial Park attack. In 1998, witnesses at the third explosion identified a possible suspect—Eric Robert Rudolph, who was ultimately linked to the four bombings by the FBI and its partners. Rudolph, however, had fled deep into the forests of North Carolina and remained a fugitive until May 2003, when he was spotted by a police officer rummaging through the trash. In 2005, he pled guilty to the bombings and was sentenced to life in prison.

The decade was also characterized by a growing internationalization of crime, a trend that was felt in Atlanta. A 1999 investigation by the FBI and the Immigration and Naturalization Service, for example, identified and busted a smuggling ring operating in Atlanta that exploited hundreds of young Asian immigrants, forcing them into prostitution and domestic slavery. The following year, Atlanta agents joined FBI offices across the globe in investigating a massive cyber attack that shut down several popular Internet websites. The investigation led to Canada, where a juvenile known as “Mafiaboy” was arrested in April 2000. He pled guilty and was sentenced in Canadian court.

Post 9/11

Following the 9/11 attacks, the Atlanta Division—like the rest of the Bureau—made preventing terrorist attacks its top priority. The office ramped up its counterterrorism efforts by expanding its Joint Terrorism Task Force and re-engineering its intelligence collection, analysis, and dissemination by creating a Field Intelligence Group.

Those capabilities were put to good use in investigating one of the FBI’s most extensive terrorism cases since 9/11. Atlanta’s investigation involved two men living in Georgia—Ehsanul Sadequee and Syed Ahmed—who had ties to terrorists around the globe. The pair communicated and conspired with—over the Internet and in person—extremists in the U.S., Canada, the U.K., Pakistan, Bosnia, and elsewhere around the globe. Among their many illegal activities, they traveled to Canada to meet with extremists and discussed potential targets for terrorist attacks in the U.S. and plans to travel to Pakistan to attend a terrorist training camp. They also made videos of the U.S. Capitol and other landmarks in the Washington, D.C. Area and sent them to terrorist recruiters overseas. Both men were indicted in 2006 and convicted at trial in the summer of 2009.

Meanwhile, the division continued handling a full load of criminal cases, including working with the Atlanta Police Department and other partners to investigate an owner of a casting/modeling company who was using his business as a front to force young women into prostitution. The man, who was also abusing the girls physically and mentally, was arrested in 2005 and sentenced to 15 years in prison in early 2008.

In 2005, the division helped respond to a tragedy in Atlanta when an ex-con named Brian Nichols who was awaiting trial overpowered a deputy sheriff at the Fulton County Courthouse and went on a shooting spree. He killed a judge, a court reporter, and a law enforcement officer before fleeing the scene. He later killed a federal agent. The FBI joined in the massive manhunt, which ultimately led to Nichols’ capture 26 hours later. Nichols was charged with more than 50 crimes and found guilty on all counts.

The next year, the office arrested three people in Atlanta for stealing trade secrets in a case that made national news. An executive assistant at Coca Cola stole a sample of a highly confidential new soda product and some detailed plans about it and then passed them off to an accomplice. That individual contacted Pepsi and tried to sell the information. Pepsi called the FBI, and the division set up a sting that nabbed the two individuals and a third accomplice. The executive assistant was convicted at trial and the two others pled guilty.

The office continues to tackle a wide variety of crimes—from health care fraud to violent prison gangs…from child pornography pedaled over the Internet to corruption in the halls of government. As the FBI enters its second century, the Atlanta Division is ready to tackle new security threats with fidelity, bravery, and integrity.