Weinberger Kidnapping

At least for residents of Long Island, New York, it was the “crime of the century” when one-month-old Peter Weinberger was kidnapped from his suburban home on July 4, 1956.

Certainly the fallout from the incident reached national proportions. This child was not from a well-to-do family, like the Lindberghs. This child came from a middle class family in suburbia—where people weren’t afraid of being targeted by extortionists. The Weinberger kidnapping struck fear in the hearts of average Americans. People started locking their doors. Almost overnight, an entire country lost its sense of security.

The Weinberger case also resulted in new legislation—signed by President Eisenhower—that reduced the FBI’s waiting period in kidnapping cases from 7 days to 24 hours.*

The Kidnapping and First Ransom Note

On that particular July 4 in 1956, Betty Weinberger wrapped her month-old son Peter in a receiving blanket and placed him in his carriage on the patio of their home in Westbury, New York. She then went inside for a few minutes while he slept.

When Mrs. Weinberger came back to check on her son, all she found was an empty carriage and a ransom note.

In the note, the kidnapper apologized for his actions but said he needed money and asked for $2,000. He promised the baby would be returned “safe and happy” the following day if his demand was met.

Despite the kidnapper’s threat to kill the baby at the “first wrong move,” she called the Nassau County Police Department.

After the kidnapping, Morris Weinberger requested that the newspapers hold off printing the story of his son’s kidnapping. All but one newspaper granted Mr. Weinberger’s request—the kidnapping made the front page of the New York Daily News.

By the following day, news reporters swarmed the drop-off area where the kidnapper requested the money be left. Police left the phony ransom package at the spot, but the kidnapper never showed up.

The Second Attempt to Collect

On July 10, six days after the kidnapping, the kidnapper called the Weinberger home—two separate times—with additional instructions on where to take the money. He didn’t show up at either location.

At the second drop site, police searched a blue cloth bag found alongside a curb. Inside the bag was a handwritten note—apparently from the kidnapper—telling the parents where to find the baby “if everything goes smooth.”

The note was examined by experts who agreed that the original ransom note and the second note were written by the same person.

The FBI Gets to Work

On July 11, after the required seven-day waiting period, the FBI entered the case.

Its first step was to establish a temporary headquarters for its employees from the New York Field Office—agent and support—in Mineola, Long Island. The temporary headquarters—which operated 24 hours a day—was under the personal direction of the special agent in charge of the New York Field Office.

The only evidence officials had—up until then—were the ransom notes. Handwriting experts from the FBI Laboratory in Washington, D.C., traveled to New York and gave special agents a crash course in handwriting analysis. These newly trained investigators began the task of examining the huge volume of handwriting specimens maintained by the New York State Motor Vehicle Bureau, federal and state probation offices, schools, aircraft plants, and various municipalities.

Handwriting Analysis Helped Solve the Case

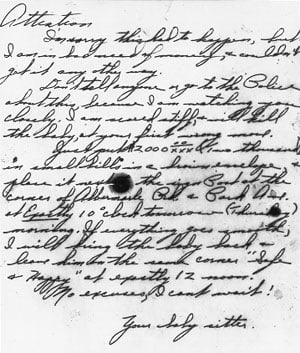

First ransom note in the Weinberger kidnapping case

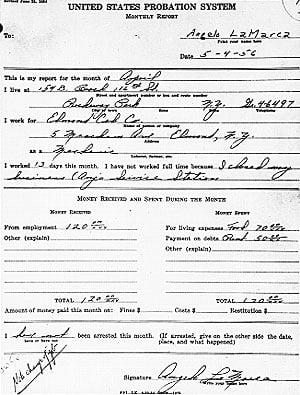

Known handwriting of Angelo La Marca

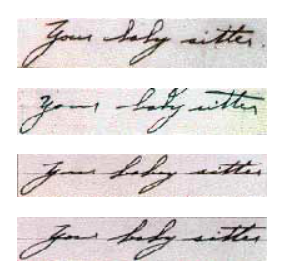

The top two signatures are from the first and second ransom notes; the bottom two signatures were known handwriting of Angelo LaMarca.

After examining and eliminating almost two million samples, the search ended on August 22, 1956. An agent at the U.S. Probation Office in Brooklyn noted a similarity between the ransom notes and writing in the probation file of one Angelo LaMarca. LaMarca had been arrested by the Treasury Department for bootlegging.

As investigators soon learned, LaMarca was a taxi dispatcher and truck driver who lived with his wife and two children in Plainview, New York. He lived in a house he couldn’t afford, had many unpaid bills and was being threatened by a loan shark. On July 4, 1956, he had found himself driving around Westbury, seven miles away, trying to figure out how to get the money he needed.

When he happened on the Weinberger house, Mrs. Weinberger was leaving her son in the baby carriage to go into her house. On impulse, LaMarca scribbled a ransom note in his truck, snatched Peter, and drove off.

The Arrest and a Tragic Discovery

On August 23, 1956, LaMarca was arrested at his home by FBI agents and Nassau County police. Although he first denied any involvement in the kidnapping of Peter Weinberger, he confessed when confronted with the handwriting comparisons.

LaMarca told investigators he went to the first drop site the day after the kidnapping—with the baby in the car—but he was scared away by all of the press and police in the area. He drove away, abandoned the baby alive in some heavy brush just off a highway exit, and went home.

A search of the area by FBI agents and Nassau County Police ensued. An FBI agent spotted a diaper pin—then the decomposed remains of Peter Weinberger. The heart-rending search was over.

In the End

Since LaMarca had crossed no state lines, he had not violated the federal kidnapping statute, and so he was turned over to Nassau County authorities for state prosecution.

In late 1956, he was tried and convicted by a jury on kidnapping and murder charges. The jury returned its verdict without a recommendation of leniency. On December 14, 1956, he was sentenced to death.

After a number of legal appeals—including one to the Supreme Court—Angelo LaMarca was executed at Sing Sing Prison on August 7, 1958.

* The “Protection of Children from Sexual Predators Act of 1998” gave federal officials the authority to enter a kidnapping investigation before the 24-hour waiting period ended.