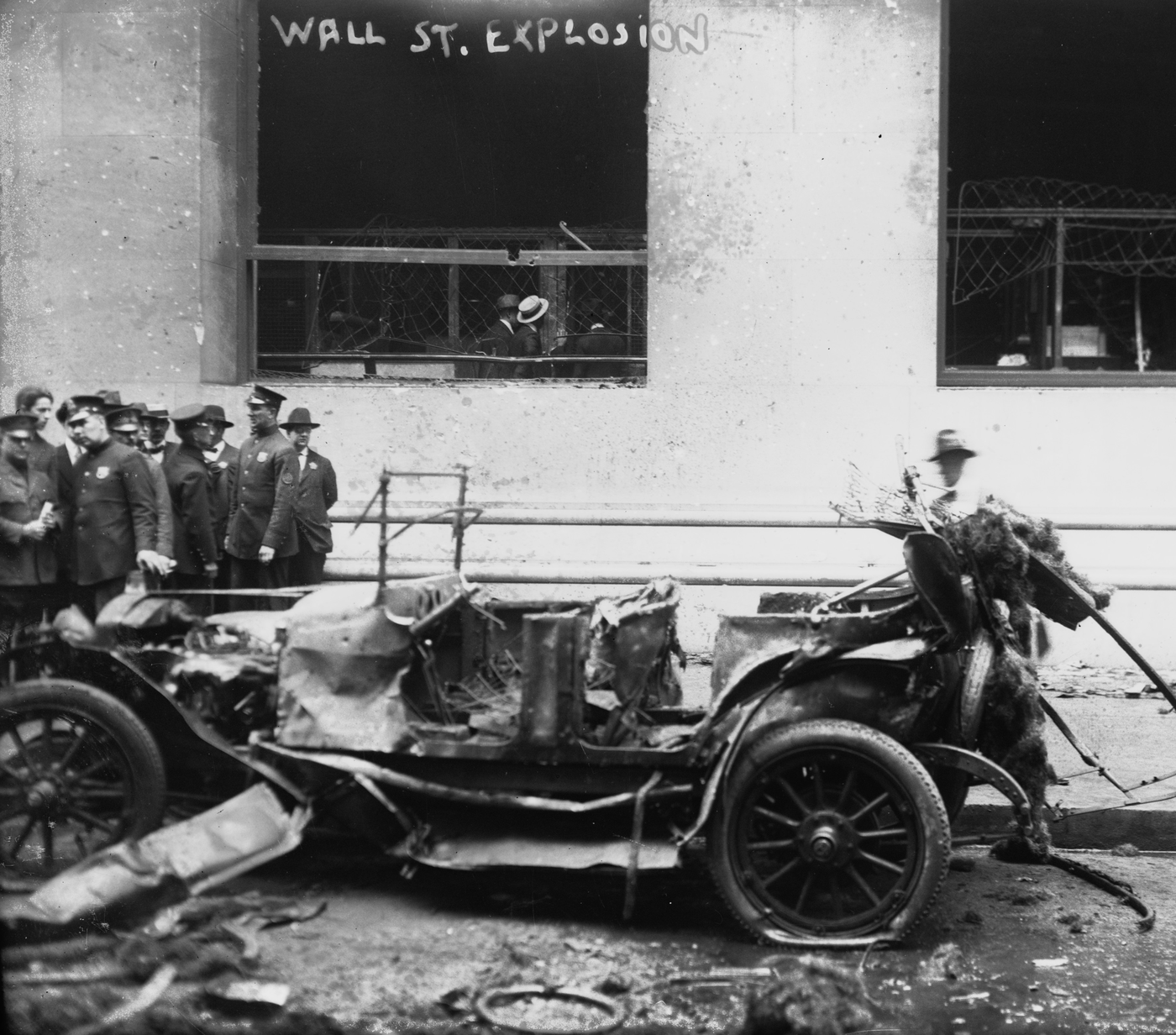

Wall Street Bombing 1920

Photographs showing the aftermath of bombing in the Wall Street financial district in New York on Sept. 16, 1920. Library of Congress photos. Click the images for higher resolution versions.

The lunch rush was just beginning as a non-descript man driving a cart pressed an old horse forward on a mid-September day in 1920.

He stopped the animal and its heavy load in front of the U.S. Assay Office, across from the J. P. Morgan building in the heart of Wall Street. The driver got down and quickly disappeared into the crowd.

Within minutes, the cart exploded into a hail of metal fragments—immediately killing more than 30 people and injuring some 300. The carnage was horrific, and the death toll kept rising as the day wore on and more victims succumbed.

Who was responsible? In the beginning it wasn’t obvious that the explosion was an intentional act of terrorism. Crews cleaned the damage up overnight, including physical evidence that today would be crucial to identifying the perpetrator. By the next morning Wall Street was back in business—broken windows draped in canvass, workers in bandages, but functioning none-the-less.

Conspiracy theories abounded, but the New York Police and Fire Departments, the Bureau of Investigation (our predecessor), and the U.S. Secret Service were on the job. Each avidly pursued leads. The Bureau interviewed hundreds of people who had been around the area before, during, and after the attack, but developed little information of value. The few recollections of the driver and wagon were vague and virtually useless. The NYPD was able to reconstruct the bomb and its fuse mechanism, but there was much debate about the nature of the explosive, and all the potential components were commonly available.

Visit our Multimedia site for more images of the Wall Street bombing of 1920. Library of Congress photos.

The most promising lead had actually come prior to the explosion. A letter carrier had found four crudely spelled and printed flyers in the area, from a group calling itself the “American Anarchist Fighters” that demanded the release of political prisoners. The letters, discovered later, seemed similar to ones used the previous year in two bombing campaigns fomented by Italian Anarchists. The Bureau worked diligently, investigating up and down the East Coast, to trace the printing of these flyers, without success.

Based on bomb attacks over the previous decade, the Bureau initially suspected followers of the Italian Anarchist Luigi Galleani. But the case couldn’t be proved, and the anarchist had fled the country. Over the next three years, hot leads turned cold and promising trails turned into dead ends. In the end, the bombers were not identified. The best evidence and analysis since that fateful day of September 16, 1920, suggests that the Bureau’s initial thought was correct—that a small group of Italian Anarchists were to blame. But the mystery remains.

For the young Bureau, the bombing became one of our earliest terrorism cases—and not the last, unfortunately, to involve the city of New York. As the decades passed, the threat from terrorism would grow and change, with different actors and causes coming and going from the scene.

The book, Hopeless Cases: The Hunt for the Red Scare Terrorist Bombers by Charles H. McCormick, University Press of America: New York, 2005, and the FBI investigative file on the case were used in the development of this article.