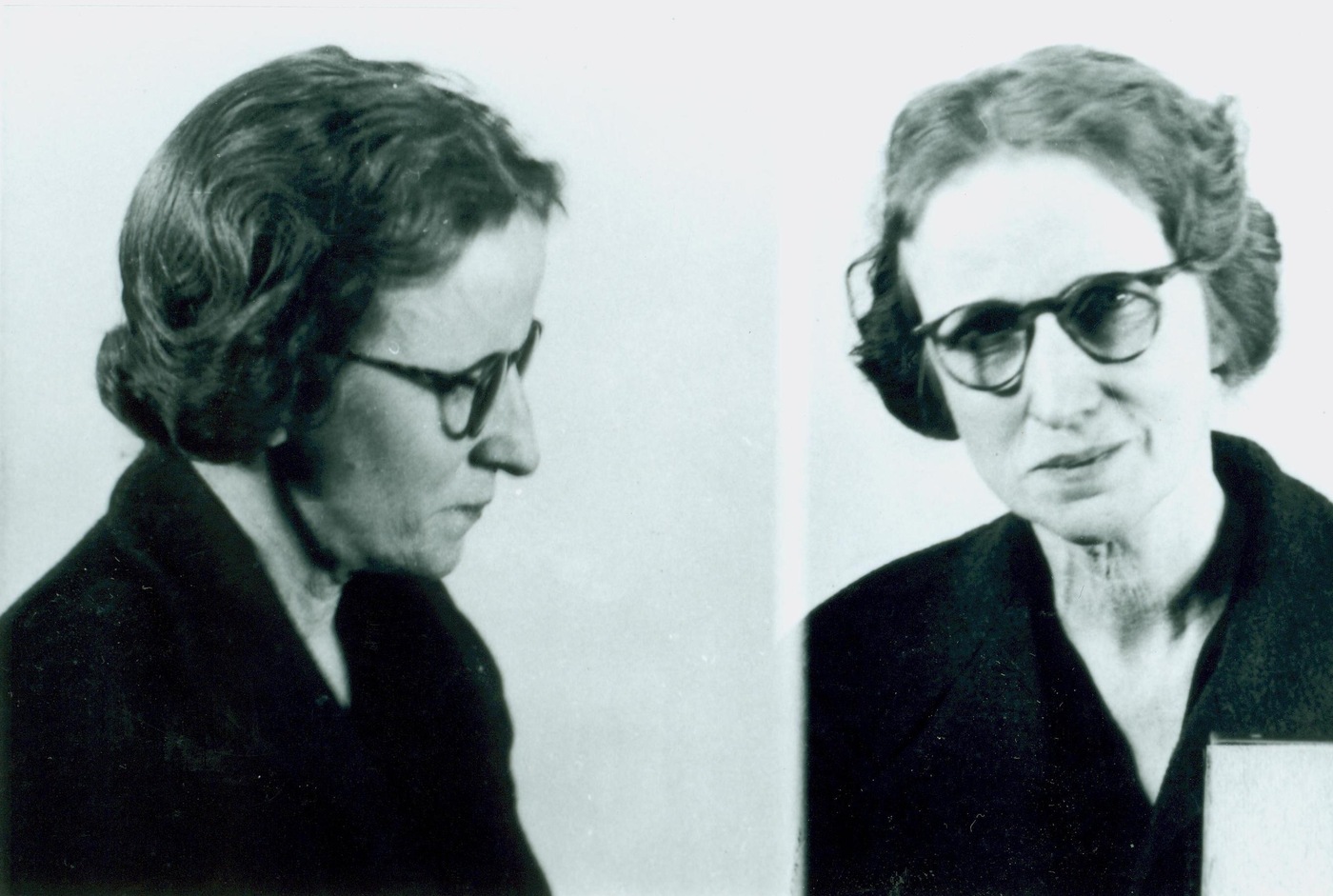

Velvalee Dickinson, the “Doll Woman”

During World War II, a New York doll shop owner used a series of letters to conceal details about U.S. naval forces that she was attempting to convey to Japan.

With the help of FBI Laboratory cryptographers and a citizen in Colorado, the Bureau tracked down and arrested this mysterious doll woman.

Background on Dickinson

Velvalee Malvena Dickinson was born on October 12, 1893 in Sacramento, California, the daughter of Otto and Elizabeth Blucher, also known as Blueher. Her father and mother were both born in the United States.

She graduated from Stanford University in Palo Alto, California in 1918, but did not receive her Bachelor of Arts degree until January 1937, because of an allegation that she had not returned certain books to the university.

In the mid-1920s, Velvalee Dickinson was employed in a San Francisco bank. She then took a position with a brokerage company in San Francisco from 1928-1935; the company was owned by her husband, Lee Terry Dickinson, for at least some of that time. Subsequently, she obtained employment in the social services field in the San Francisco area.

In 1937, Mrs. Dickinson and her husband moved to New York City, where she obtained employment as a doll saleswoman in a department store until December 31, 1937.

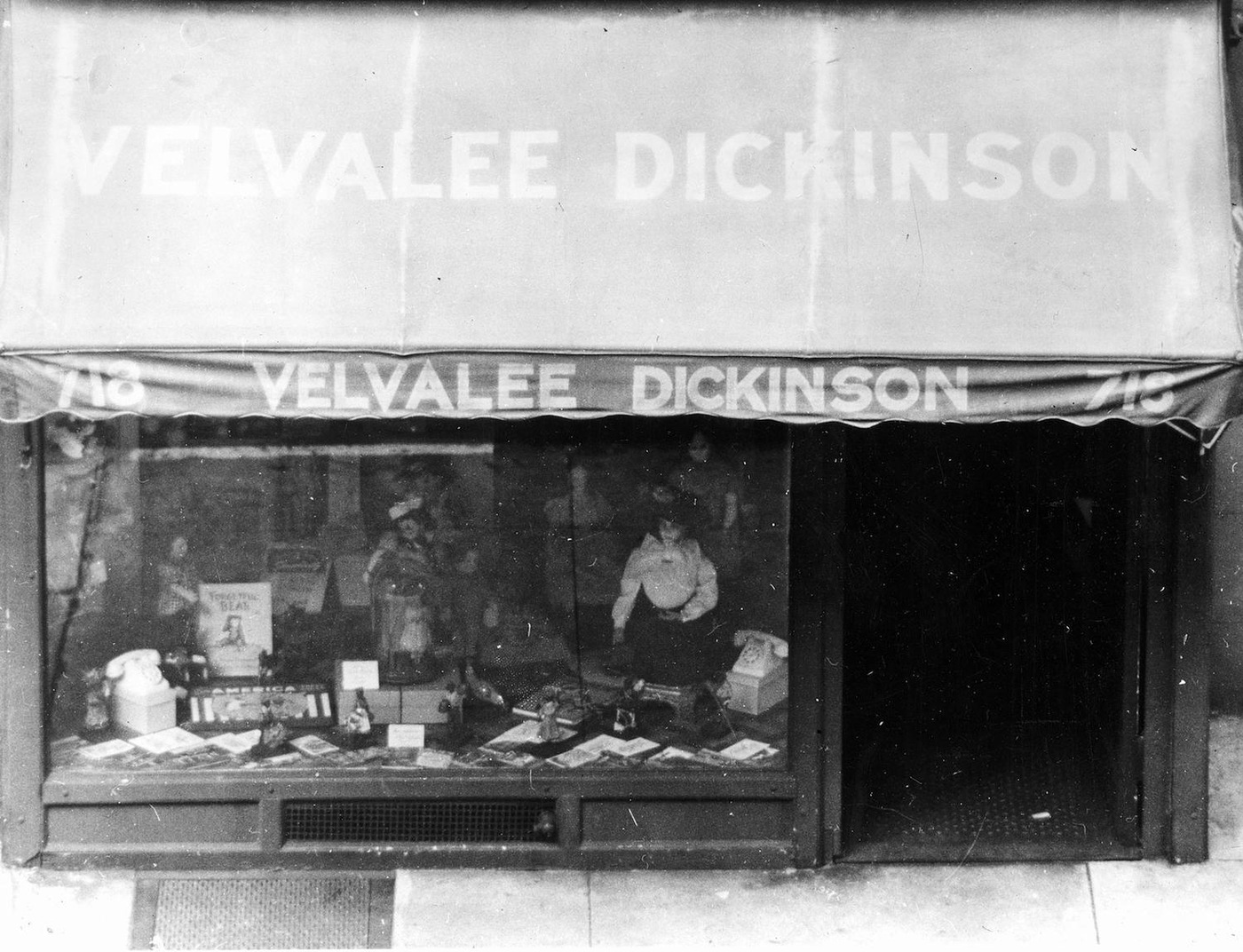

Mrs. Dickinson then began operating her own doll store, first at her residence at 680 Madison Avenue, then at a separate store at 714 Madison Avenue.

In October 1941, she opened her store at 718 Madison Avenue, at which location she catered to wealthy doll collectors and hobbyists interested in obtaining foreign, regional, and antique dolls.

Mrs. Dickinson’s husband assisted his wife in the operation of her doll business by handling the accounting records of transactions, including those involving the sale of dolls to influential individuals throughout the United States.

Mr. Dickinson, who suffered from a heart ailment, died on March 29, 1943.

The Letters

The FBI’s interest in Mrs. Dickinson stemmed from a letter about dolls intercepted by wartime censors because of its unusual contents and brought to the Bureau’s attention in February 1942.

The letter, purportedly from a Portland, Oregon woman to an individual in Buenos Aires, Argentina, dealt with a “wonderful doll hospital” and observed that the writer had left her three “Old English dolls” for repairs. Also mentioned in the letter were “fish nets” and “balloons.”

FBI Laboratory cryptographers examined the letter and concluded that the “three Old English dolls” probably were three warships and the doll hospital was a shipyard where repairs were made. They further concluded that the fishing nets referred to submarine nets protecting ports on the West Coast and that the reference to balloons was intended to convey information about other defense installations on the West Coast.

Based on the examination of the above letter, the FBI began an investigation to determine whether information about U.S. defense matters was being transmitted to the enemy.

In the meantime, four more letters addressed to the same individual in Buenos Aires began arriving at the homes of the ostensible senders with the notation, “Address Unknown.” These letters were turned over to the FBI. The persons whose names had appeared on the envelopes as the senders stated that the signatures on the letters resembled theirs and that the letters contained correct information about their personal lives and interest in dolls. The four emphatically denied, however, that they had sent any of the letters.

One of these letters, purportedly sent by a Springfield, Ohio woman, had been postmarked New York City. The letter, also dealing with dolls, contained the words, “Distroyed YOUR” and in the same sentence made reference to a Mr. Shaw who had been ill but would be back to work soon. Significantly, this letter was written a short time after it became known that the Destroyer Shaw, which had had its bow blown off at Pearl Harbor, was being repaired in a West Coast shipyard and soon would rejoin the fleet.

Another of the letters, furnished to the FBI in August 1942 by a Colorado Springs, Colorado woman, was postmarked Oakland, California. It made reference to seven small dolls which the writer said she would attempt to make look as if they were “seven real Chinese Dolls” making up a family consisting of a father, grandmother, grandfather, mother, and three children. This letter took on particular significance when the FBI learned that several warships had come into San Francisco Bay for repairs just before the time the letter was written and mailed certain details about the ships involved, if known to the enemy, would have been of tremendous value to them.

The Portland, Oregon woman, whose name had appeared as the writer of the letter intercepted by censors in February 1942, submitted to the Bureau a letter returned to her by the Post Office in August 1942. This one was dated in May 1942 and postmarked Portland, Oregon. The letter read in part: “I just secured a lovely Siamese Temple Dancer, it had been damaged, that is tore in the middle. But it is now repaired and I like it very much. I could not get a mate for this Siam dancer, so I am redressing just a small plain ordinary doll into a second Siam doll...”

FBI cryptographers made the following interpretation of the above: “I just secured information of a fine aircraft carrier warship, it had been damaged, that is torpedoed in the middle. But it is now repaired and I like it very much. They could not get a mate for this so a plain ordinary warship is being converted into a second aircraft carrier...”

This letter had been written a few days after the aircraft carrier USS Saratoga left Puget Sound for San Diego.

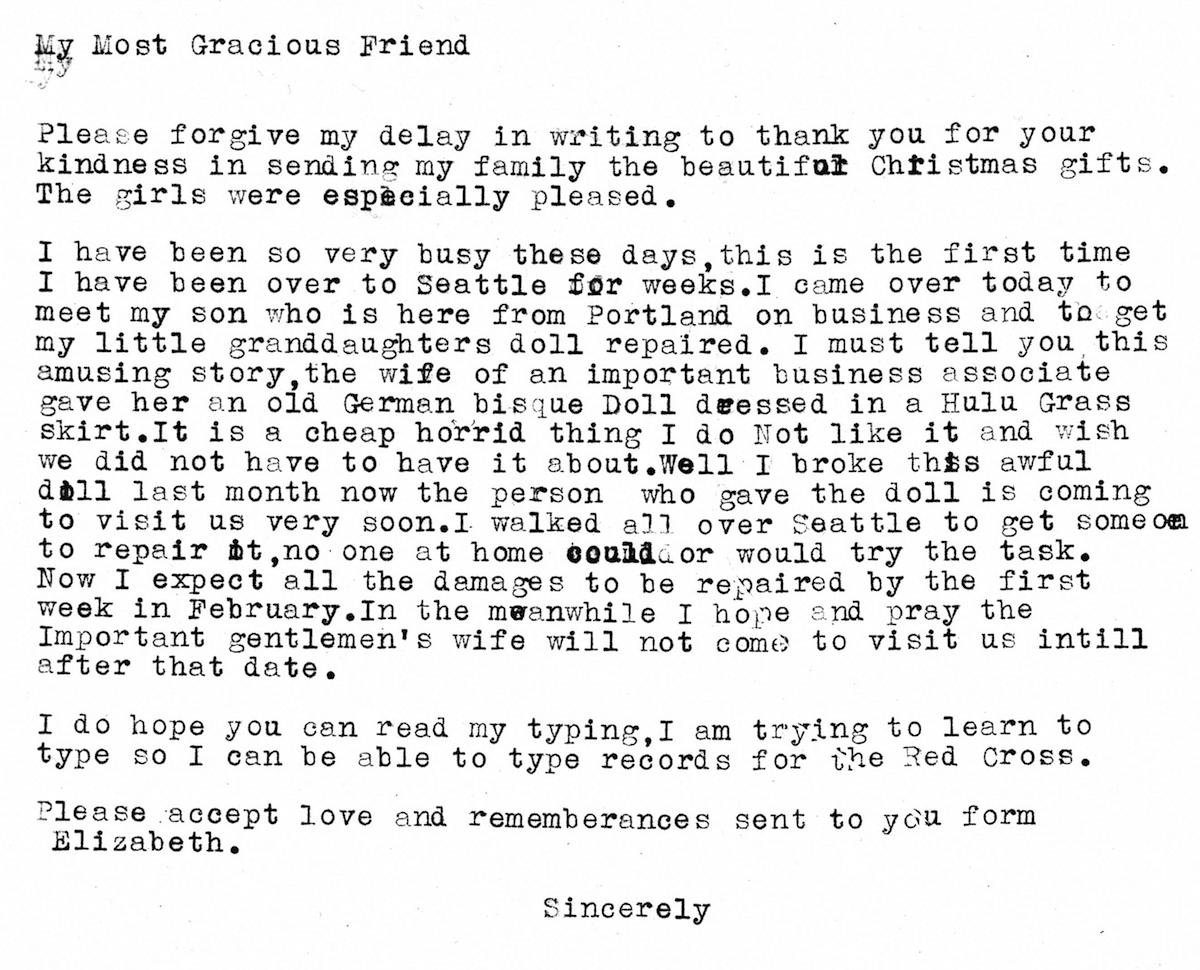

Still another letter (pictured) was turned over to the FBI by a Spokane, Washington woman, this one carrying a Seattle, Washington postmark. The letter referred to a “German bisque doll,” dressed in a hula grass skirt, which was reported to be in Seattle for repairs scheduled for completion by the first week in February.

A check by the FBI with naval authorities verified the conclusion that the doll referred to a warship which had been damaged at Pearl Harbor. The vessel was in Puget Sound Navy Yard for repairs at the time the letter was written.

FBI Laboratory examination of all five letters confirmed that the signatures on the letters were not genuine, but were forgeries which the experts decided were prepared from original signatures in the possession of the forger. The examination also showed that the typewriter used in the preparation of the letters was different in each case, but that the typing characteristics indicated that the letters were prepared by the same person.

The conclusion reached by the FBI cryptographers was that an open code was used in the letters, which attempted to convey information on the U.S. Armed Forces, particularly the ships of the U.S. Navy, their location, condition, and repair, with special emphasis on the damage of such vessels at Pearl Harbor.

The woman from Colorado Springs provided the information that directed the FBI’s attention to Velvalee Dickinson, the doll shop owner from New York City. She expressed the belief that Mrs. Dickinson had used her signature on one of the letters in a spirit of vindictiveness because the woman had purchased some dolls from Mrs. Dickinson and had been unable to pay for them promptly. Others of the women who had received the letters returned from Buenos Aires also voiced their suspicions of Mrs. Dickinson as the sender.

Typewritten letters dealing with dolls received on past occasions by one of these women from Mrs. Dickinson were identified by the FBI with the typewriting on one of the letters that had been addressed to Buenos Aires. Thus it was determined that Mrs. Dickinson’s typewriter had been responsible for at least one of the letters to Buenos Aires. FBI investigation also disclosed that all four of the women whose signatures had been used on the Buenos Aires letters had corresponded in the past with Mrs. Dickinson concerning doll collections.

Further FBI investigation revealed that in the early and mid-1930s, while she was still in the San Francisco area, Mrs. Dickinson had been a member of the Japan-American Society. During one year, her dues to the society were paid by an attaché of the Japanese Consulate in San Francisco. It was also determined that she had made frequent visits to the Japanese Consulate in that city, attended important social gatherings in San Francisco at which Japanese Navy members and other high Japanese government officials were present, and entertained many Japanese in the Dickinson’s home.

The FBI also learned that after moving to New York City, Mrs. Dickinson had visited the Nippon Club and the Japan Institute, had cultivated the friendship of the Japanese Consul General there, and had met Ichiro Yokoyama, the Japanese Naval Attaché from Washington, D.C.

In tracing Mrs. Dickinson’s activities from January 1942 through June 1942 (the time frame in which the five doll letters had been sent), the FBI found that the Dickinson’s had been in the areas from which the letters had been postmarked at the time the letters were sent. The hotels at which the couple had stayed on the West Coast were also located, and FBI examination showed that typewriters owned and available to guests at these hotels were used in the preparation of four of the letters sent to Argentina.

Continuing FBI investigation disclosed that Mrs. Dickinson had consistently borrowed money from banks and business associates in New York City as late as 1941. However, in early 1943, she was known to have had in her possession a large number of $100 bills. Four of the bills which she had used in transactions were traced by the FBI to Japanese official sources, which had received the money before the war.

Arrest and Guilty Plea

Based on the results of the FBI’s investigation, Bureau agents arrested Velvalee Dickinson on January 21, 1944 in the bank vault in which she kept her safe deposit box.

On February 11, 1944, she was indicted by the federal grand jury in the Southern District of New York for violation of the censorship’ statutes, conviction of which could result in a maximum penalty of 10 years in prison and a $10,000 fine. She pleaded not guilty and was held in lieu of $25,000 bail.

FBI examination of the contents of the safe deposit box disclosed some $13,000 which was traceable to Japanese sources. A portion of the money had been in the hands of captain Yuzo Ishikawa of the Japanese Naval Inspector’s Office in New York City before coming into the possession of Mrs. Dickinson.

Mrs. Dickinson had told the arresting agents that the money in the safe deposit box had come from insurance companies, a savings account, and her doll business. Upon interview later, Mrs. Dickinson stated that the money in the box actually had come from her husband. She alleged that she found this money hidden in her husband’s bed at the time of his death. Mrs. Dickinson said that her husband had not told her the source of the money but she believed it might have come from the Japanese Consul in New York City.

Meanwhile, information compiled as a result of the FBI’s continuing investigation resulted in another indictment of Mrs. Dickinson on May 5, 1944, this time on charges of violating the espionage statutes, the Registration Act of 1917, and the censorship statutes. She pleaded not guilty, and her bail of $25,000 was continued.

On July 28, 1944, an agreement was made between the U.S. Attorney and Mrs. Dickinson’s attorney whereby the espionage and Registration Act indictments were dismissed, and Mrs. Dickinson pleaded guilty to the censorship violation and promised to furnish information in her possession concerning Japanese intelligence activities.

Following her guilty plea, Mrs. Dickinson admitted to FBI agents that she had typed and prepared the five letters addressed to the individual in Argentina and that she had used correspondence received by her from her customers to forge their signatures thereon. She claimed that the information incorporated in her letters was obtained through questioning innocent and unwitting citizens in the Seattle area around the Bremerton Navy Yard, the Mare Island Navy Yard in San Francisco, and from personal observation. She stated that the letters transmitted information about aircraft carriers and battleships damaged at Pearl Harbor, and that names of the dolls appearing in the letters referred to these types of vessels.

According to Mrs. Dickinson, the code to be used in the letters, instructions for the use of the code, and $25,000 in $100 bills had been passed to her husband by Japanese Naval Attaché Ichiro Yokoyama on or about November 26, 1941 in her doll store at 718 Madison Avenue for the purpose of supplying information to the Japanese. She repeated her claim that for the most part the money had been hidden in her husband’s bed until his death.

Investigation by the FBI belied her claims. That investigation disclosed that while Mrs. Dickinson knew the Japanese Naval attaché well, her husband did not know him at all. It was also learned that a doctor’s examination of Mr. Dickinson had shown that Dickinson’s mental faculties were impaired at the time of the supposed Japanese payment to him. As for Mrs. Dickinson’s claim that the money had been hidden in her husband’s bed until his death, both the nurse and the maid employed by the Dickinsons at that time emphatically stated that no money was concealed there.

On August 14, 1944, Velvalee Dickinson appeared in court for sentencing. As the sentence was imposed, the court commented, “It is hard to believe that some people do not realize that our country is engaged in a life and death struggle. Any help given to the enemy means the death of American boys who are fighting for our national security. You, as a natural-born citizen, having a University education, and selling out to the Japanese, were certainly engaged in espionage. I think that you have been given every consideration by the Government. The indictment to which you have pleaded guilty is a serious matter. It borders close to treason. I, therefore, sentence you to the maximum penalty provided by the law, which is ten years and $10,000 fine.”

Still maintaining her innocence and contending that her deceased husband, and not she, was the traitor to her country, Mrs. Dickinson was removed to the Federal Correctional Institution for Women at Alderson, West Virginia. She was conditionally released on April 23, 1951, to the supervision of the federal court system.