Rumrich Nazi Spy Case

It was the FBI’s first major international spy case: on December 2, 1938—less than a year before World War II broke out in Europe—three Nazi spies were found guilty of espionage in the United States.

And the man who had exposed the ring, Guenther Rumrich, was sentenced to a reduced prison term for his cooperation.

But it was hardly a roaring success for the FBI. Four times as many spies had escaped, including the biggest fishes. The Bureau was roundly criticized in the press, and for good reason, as it was simply unprepared at that point in history to investigate such cases of espionage.

It all began that February when the crafty Rumrich—a naturalized U.S. citizen recruited by German intelligence—was arrested by the New York Police Department for the U.S. Army and the State Department, following a tip by British intelligence. The charge: impersonating the Secretary of State in order to get blank U.S. passports.

Rumrich was willing to talk, confessing that he was acting on behalf of Nazi agents and saying he’d provide the name of 10 to 15 spies working for Germany.

But who would lead the investigation? The Department of State, the FBI, and what was then called the War Department debated the issue.

Director J. Edgar Hoover didn’t want to take it on, believing that the lack of coordination between agencies had already compromised the case. But the War Department insisted, and the case landed squarely in our lap.

An experienced criminal agent named Leon Turrou was placed in charge. Turrou debriefed Rumrich and other agent German agents and interviewed Dr. Igantz Greibl, head of the U.S. German intelligence ring. But after each interview, Turrou told the spies that they’d need to testify before a grand jury, and most fled the country to avoid prosecution. Turrou’s background simply didn’t prepare him for the nuances of an espionage case. Worse yet, he leaked information about the case to the New York press and even agreed to write a series of articles for one paper.

In June 1937, Turrou was fired for breaking the FBI oath. But his damage was far from done. When he took the stand at the trial of the few remaining suspects in October 1938, he was accused being an overzealous government agent motivated by profit and fame, of tampering with witnesses, and even of taking a bribe from Dr. Greibl. Despite the convictions, the FBI looked unprofessional and unprepared to protect the nation from espionage.

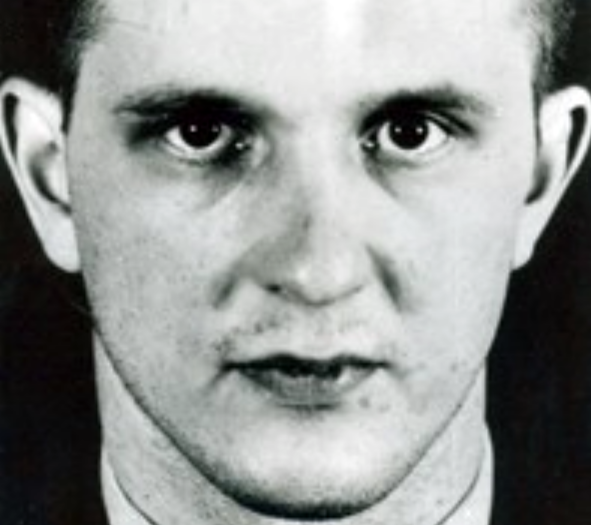

Guenther Rumrich

Special Agent Leon Turrou

In response, the FBI immediately began reforming its counterintelligence operations. The Bureau trained agents on how to conduct espionage investigations and how to the make the U.S. a more difficult operating environment for foreign agents. Since the Rumrich case was based solely on statements by the spies themselves, the FBI also began developing other tools and techniques to corroborate testimony.

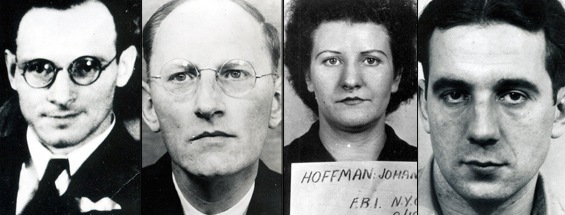

One who got away and three who didn’t: (left to right), Dr. Ignatz Greibl, who fled; and the three convicted spies, Otto Hermann Voss (six years), Johanna Hoffman (four years), and Erich Glaser (two years).

That we learned our lessons quickly is clear in the 1941 Duquesne Spy Ring case, where we took extensive surveillance footage of German agents in carefully staged settings. The case devastated Nazi intelligence in this nation before the U.S. even entered the war.

The Rumrich case, though seriously flawed, ultimately helped the FBI mature into an effective force for protecting national security. Just in time, as a Cold War was looming.