Pearl Harbor Spy

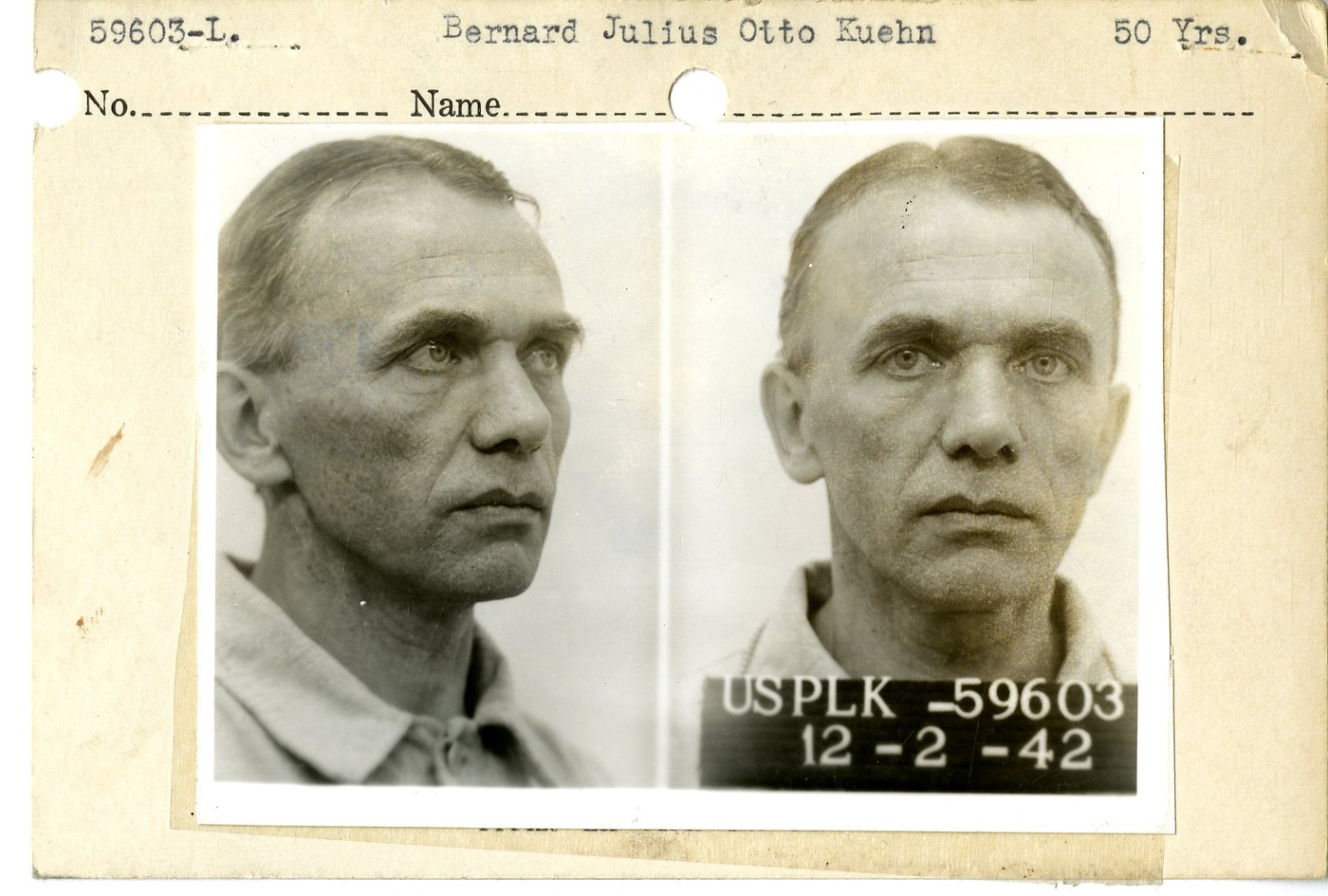

On February 21, 1942, just 76 days after the tragic attack on Pearl Harbor, Bernard Julius Otto Kuehn was found guilty of spying and sentenced to be shot “by musketry” in Honolulu.

What was a German national doing in Hawaii in the days leading up to the attack? What exactly did Kuehn do to warrant such a sentence? Here’s the story.

Bed sheets on clothes lines. Lights in dormer windows. Car headlights. A boat with a star on its sail.

Otto Kuehn had a complex system of signals all worked out. A light shining in the dormer window of his Oahu house from 9 to 10 p.m., for example, meant that U.S. aircraft carriers had sailed. A linen sheet hanging on a clothes line at his home on Lanikai beach between 10 and 11 a.m. meant the battle force had left the harbor. There were eight codes in all, used in varying combinations with the different signals.

In November 1941, Kuehn had offered to sell intelligence on U.S. warships in Hawaiian waters to the Japanese consulate in Hawaii. On December 2, he provided specific—and highly accurate—details on the fleet in writing. That same day, he gave the consulate the set of signals that could be picked up by nearby Japanese subs.

Kuehn—a member of the Nazi party—had arrived in Hawaii in 1935. By 1939, the Bureau was suspicious of him. He had questionable contacts with the Germans and Japanese. He'd lavishly entertained U.S. military officials and expressed interest in their work. He had two houses in Hawaii, lots of dough, but no real job. Investigations by the Bureau and the Army, though, never turned up definite proof of his spying.

Not until the fateful attack of December 7, 1941. Honolulu Special Agent in Charge Robert Shivers immediately began coordinating homeland security in Hawaii and tasked local police with guarding the Japanese consulate. They found its officials trying to burn reams of paper. These documents—once decoded—included a set of signals for U.S. fleet movements.

All fingers pointed at Kuehn. He had the dormer window, the sailboat, and big bank accounts.

Kuehn was arrested the next day and confessed, though he denied ever sending coded signals. His sentence was commuted—50 years of hard labor instead of death “by musketry”—and he was later deported.

Mug shot of Bernard Julius Otto Kuehn in 1942. National Archives photograph.

The attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941. Library of Congress photograph.

Additional Information

- FBI Vault Records on the Case

- National Archives Images and Files on Kuehn