Osage Murders Case

A deadly conspiracy against the Osage Nation and the agents who searched for answers

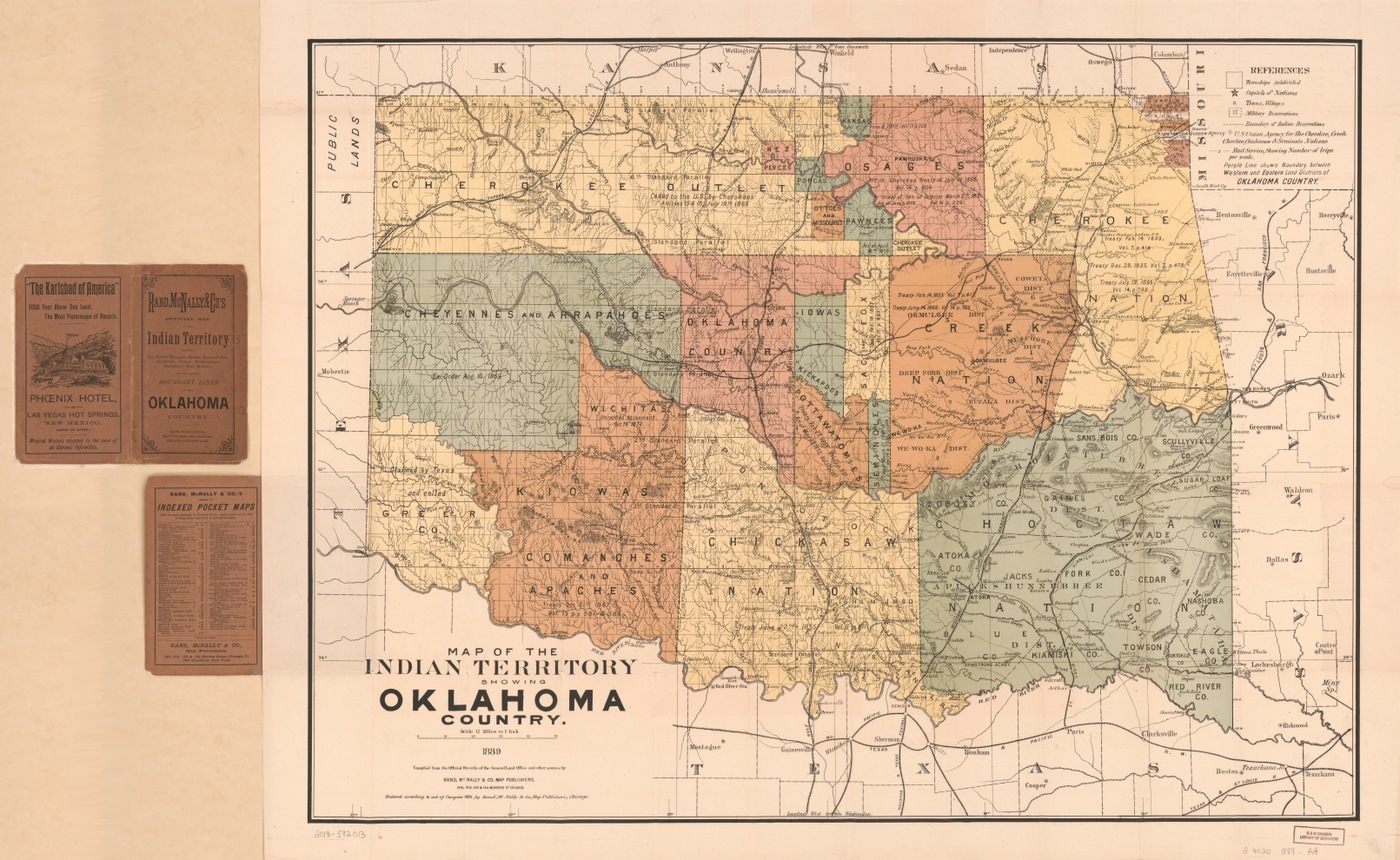

Map of Oklahoma Indian Territory, 1889

Oil in Osage

In the late 1800s, oil was discovered on the Osage Indian Reservation in present-day Osage County, Oklahoma. The members of the Osage Nation earned royalties from oil sales through their federally mandated “head rights,” and, as the oil market expanded, they became incredibly wealthy.

As word spread, opportunists flocked to Osage lands seeking to separate the Osage from their wealth by any means necessary—even murder.

The Reign of Terror

It was May 1921 when the decomposed body of Anna Brown—an Osage Native American—was found in a remote ravine in northern Oklahoma. The undertaker later discovered a bullet hole in the back of her head. Anna had no known enemies, and the case went unsolved.

That might have been the end of it, but, just two months later, Anna's mother Lizzie Q suspiciously died. Two years later, her cousin Henry Roan was shot to death. Then, in March 1923, Anna's sister and brother-in-law, Rita and Bill Smith, were killed when their home was bombed.

Anna Brown

Anna's last living sibling, Mollie Burkhart, was left devastated—and suspiciously afflicted with an ongoing illness.

One by one, at least two dozen people—including Osage Native Americans, a well-known oilman, and others—in the area inexplicably turned up dead.

And anyone who shared suspicions and accompanying evidence about what may be going on was met with death threats—or killed, like attorney W.W. Vaughn, who was thrown from a train.

Newspapers described the murders and fear during this time as the Reign of Terror.

The Investigation

Who was behind all the murders?

Ravine in Osage Hills, Oklahoma, where the murdered body of Anna Brown was found.

That's what the terrorized community wanted to find out. But a slew of private detectives and other investigators turned up nothing, and some were even trying to sidetrack honest efforts.

The Osage Tribal Council asked the federal government to send detectives to investigate. After receiving the petition in April 1923, the newly created Bureau of Investigation (the agency that would become the FBI) assigned agents to the case.

Early on, all fingers pointed at William Hale, the so-called King of the Osage Hills. Hale arrived in Oklahoma as a local cattleman, and he bribed, intimidated, lied, and stole his way to wealth and power. He grew even greedier when oil was discovered on the Osage Indian Reservation.

Hale's connection to Anna Brown's family was clear: His nephew, Ernest Burkhart, was married to Anna’s sister Mollie.

And if Anna, her mother, and two sisters died—in that order—all head rights would pass to Ernest, and Hale could take control. The prize? Half-a-million-dollars a year—or more.

Solving the case was another matter.

William Hale

The locals weren’t talking; Hale had threatened or paid off many of them, and the rest had grown distrustful of outsiders. Hale also planted false leads that sent our agents scurrying across the Southwest.

Tom White led a team of four agents who went undercover as an insurance salesman, cattle buyer, oil prospector, and herbal doctor to turn up evidence. Over time, they gained the trust of the Osage as they built the case.

Finally, Hale's nephew talked. Then others confessed. Agents proved that Hale ordered the murders of Anna and her family to inherit their oil rights, cousin Henry for the insurance, and others who had threatened to expose him. It's alleged they attempted to kill Mollie by poisoning her, but their attempts were unsuccessful.

In January 1929, Hale was convicted and sent to prison. His henchmen—including a hired killer and crooked lawyer—also got time.