Medgar Evers

It took more than three decades, but justice was finally served in the 1963 murder of a pioneering civil rights leader in Jackson, Mississippi.

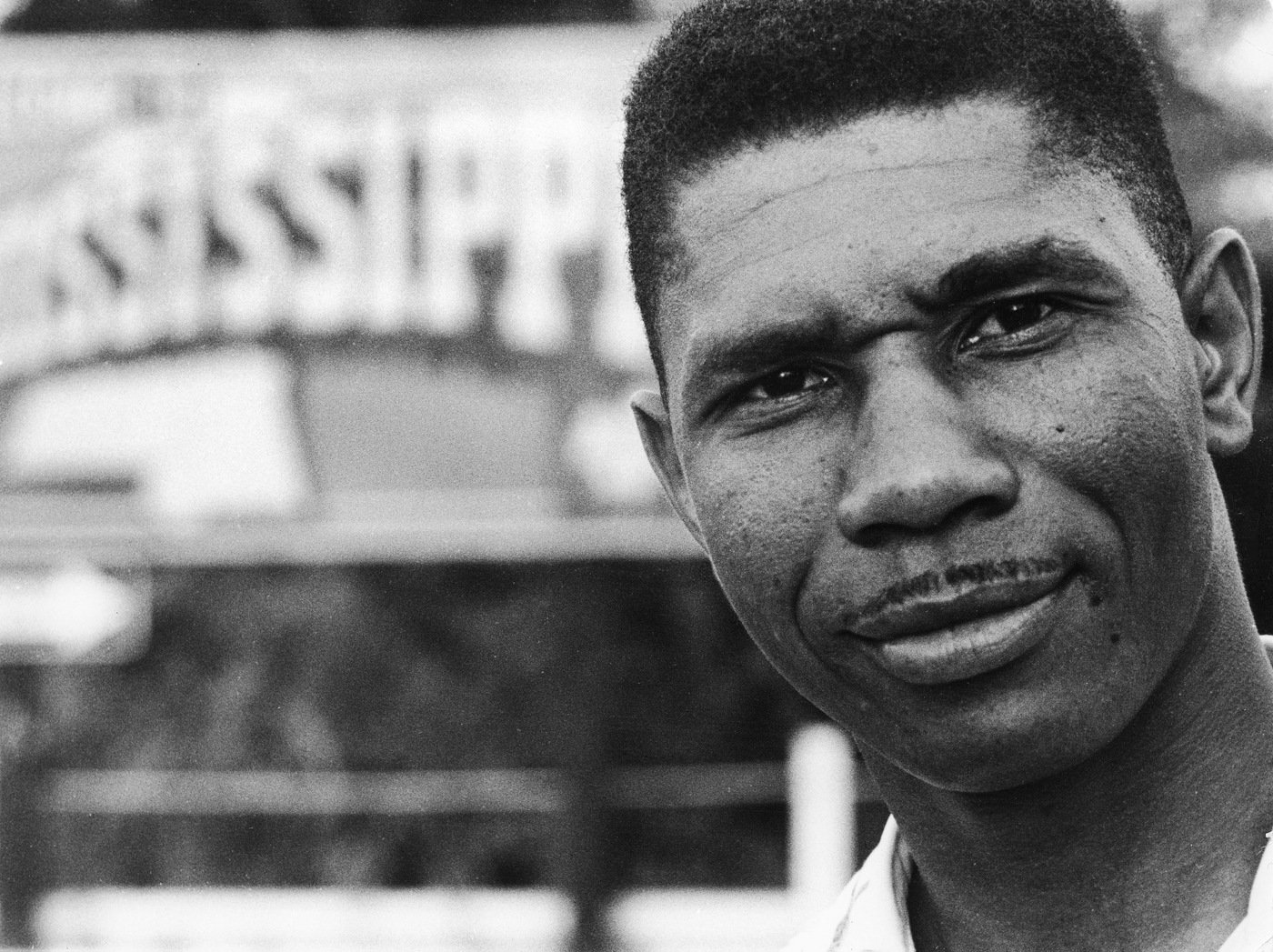

Medgar Evers stands near a sign of the state of Mississippi in 1958. AP Photograph.

About half past midnight, a shot rang out.

It was June 12, 1963, in a suburban neighborhood of Jackson, Mississippi. A 37-year-old civil rights activist named Medgar Evers had just come home after a meeting of the NAACP.

As he began the short walk up to his single-story rambler, the bullet struck Evers in the back. He staggered up to the steps of the house, then collapsed.

Across the street on a lightly wooded hill, another man jumped up in pain. The recoil from the Enfield rifle he had just fired drove the scope into his eye, badly bruising him. He dropped the weapon and fled.

Meanwhile, Evers’ wife and three children—still awake after watching an important civil rights speech by President John F. Kennedy—heard the shot and quickly came outside. They were soon joined by neighbors and police. His wounds severe, Evers died within the hour.

Leading the investigation, the local police immediately found the rifle and determined that it had been recently fired. Back at the station, a fingerprint was recovered from the scope and submitted to the FBI.

The FBI connected it to a man named Byron De La Beckwith based on its similarity to his military service prints. He was arrested several days later.

Beckwith, a known white supremacist and segregationist, had been asking around to find out the location of Evers’ home for some time prior to the shooting.

With the obvious motive, his fingerprint on the weapon, the injury around his eye, his planning, and other factors, Beckwith clearly appeared to be the killer.

In two separate trials, local prosecutors presented a strong case. A number of police, FBI experts, and others testified on different parts of the evidence against Beckwith.

But this was the 1960s, and in both trials, all-white juries did not reach a verdict. Beckwith went free.

By the early 1990s, however, the time was ripe to revisit the case.

Evers’ widow, Myrlie—a formidable civil rights organizer in her own right—asked local prosecutors to reopen the investigation and see if other evidence could be found. The FBI again provided its assistance.

In December 1990, a new grand jury returned an indictment against Beckwith based on witnesses finally willing to tell their stories, including hearing the white supremacist brag how he had killed Medgar Evers.

This time, justice was done. Beckwith was convicted in 1994 and sentenced to life in prison.

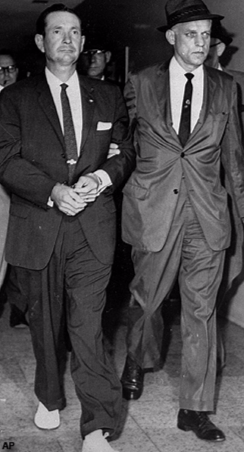

Byron De La Beckwith (left) is escorted to the Jackson police station by FBI agents on June 23, 1963. AP photograph.

The murder of Medgar Ever was a loss to his family, the community, and the nation.

Evers was a devoted husband and father, a distinguished World War II veteran, and a pioneering civil rights leader. He served as the NAACP’s first field secretary in Mississippi—organizing protests and voter registration drives, recruiting new workers into the civil rights movement, and pushing for school integration.

But his death in 1963 was not in vain. The brutal, senseless murder helped galvanize the nation in its steady march towards equality and justice.