Judge Vance Murder

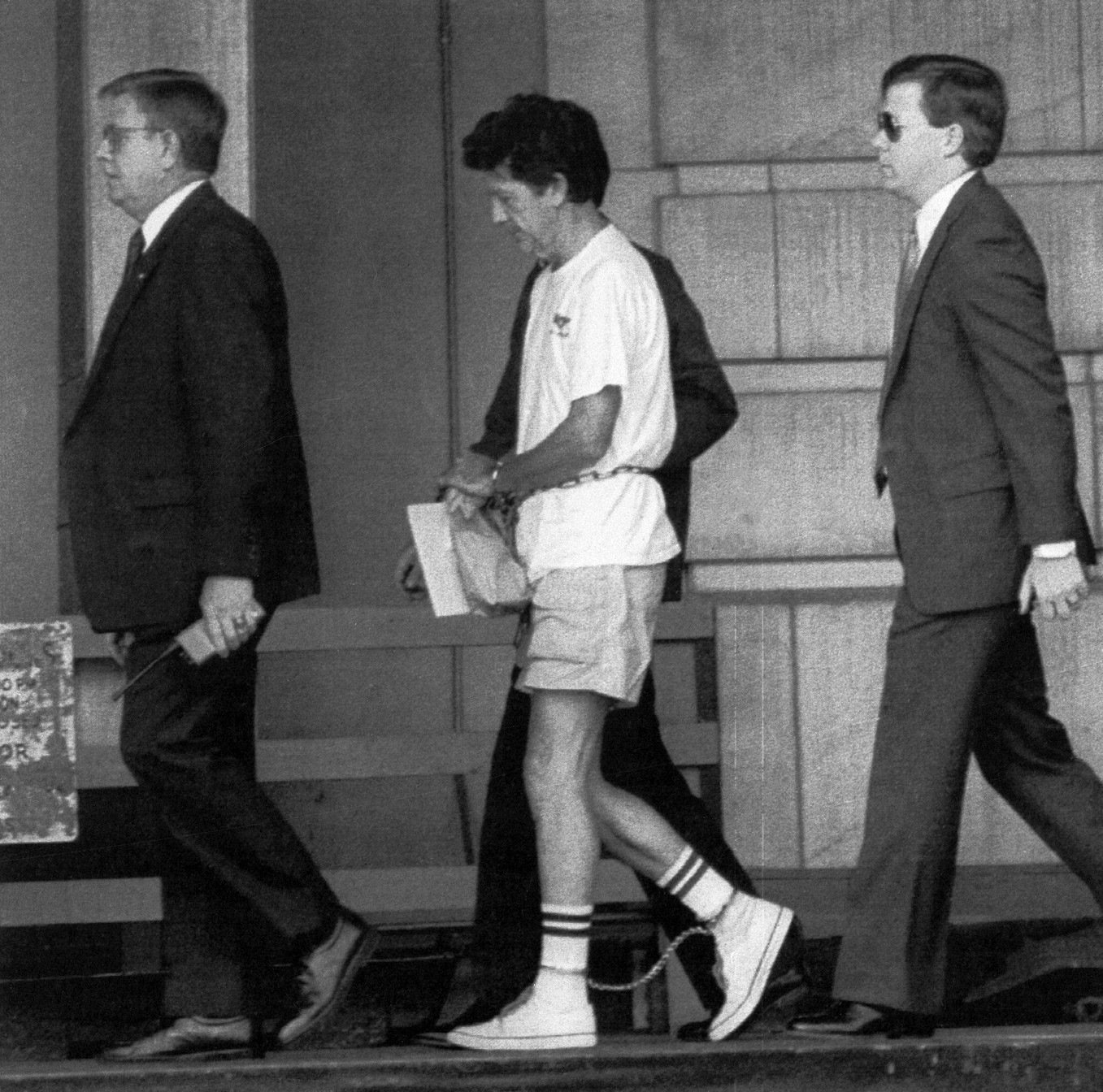

Walter Moody (center) is led into a federal courthouse in Macon, Georgia, during a hearing in 1990. Bettmann/CORBIS photo.

Getting a plainly wrapped package in the mail wasn’t all that surprising. It was the holidays, after all. What was inside was another matter. It was a bomb.

When federal appeals Judge Robert Vance opened the small brown parcel in the kitchen of his suburban Alabama home on December 16, 1989, it exploded, killing him instantly and seriously injuring his wife.

Two days later, virtually the same scenario happened again. This time, the victim was Atlanta Attorney Robert Robertson.

It wasn’t over. Two more bombs mysteriously appeared. The third, sent to the federal courthouse in Atlanta, was intercepted. A fourth was recovered after being mailed to the Jacksonville office of the NAACP. Through brave and careful work, ATF personnel defused the one bomb and Florida police bomb experts the other.

The murders and serial bombings stunned the nation. Who’d be spiteful enough to send mail bombs during the holidays?

That’s what the FBI aimed to find out. We started with the obvious. Both men were known for their work in civil rights. But that turned out to be a red herring.

Meanwhile, with extensive help from U.S. postal inspectors, we’d gathered the remnants of the bombs and packages for our Lab to analyze, learned the path the packages had taken through the postal system, and assembled a long list of suspects.

A break came when an ATF expert was contacted by a colleague who had helped defuse one of the bombs. He thought it resembled one he’d seen 17 years before. And he remembered the name of the person who had built it—Walter Leroy Moody.

With this lead, the Bureau and its partners began an extensive probe of the events—purchases, contacts, phone calls, etc.—and ultimately linked both the exploded and unexploded bombs to each other and to Moody. Court authorized surveillance of Moody at home and in jail (he talked to himself) provided additional evidence. Other leads were followed, suspects eliminated or linked to the crimes, and detailed analysis done on every bit of evidence, information, and trail that we came across.

Over the next year, Moody’s motive became clear. We found a pattern of experimentation with bombs dating back to the early 1970s when Moody was convicted of possessing a bomb that had hurt his wife when it exploded. His conviction and failed appeals in that case had led him to harbor a long-festering resentment of the court system. His contact with Judge Vance in a 1980s case led to even deeper resentment and a personal animus that led to revenge. The other bombs, we determined, were meant to make us suspect that racism was the motive.

By the spring of 1991, with the help of prosecutor (and future FBI Director) Louis Freeh, a solid case had been developed. The trial was difficult. Moody had made every effort to conceal his connection to the bombings.

On June 28, 1991, based on the extensive investigative work of the FBI, the ATF, the IRS, the U.S. Marshals, the Georgia State Police, and many others, the jury found Moody guilty of more than 70 charges and sentenced him to life in prison. He was executed in 2018.

It ended up one of the largest cases in FBI history—and an important one, as protecting our nation’s judges is a responsibility we take very seriously.