Fur Dressers Case

Louis “Lepke” Buchalter and his gang of mobsters were busted thanks to an FBI investigation into a fur dressing racket in the 1930s.

Overview

Jacob “Gurrah” Shapiro surrendered to federal authorities on April 14, 1938 in New York, after being a fugitive from justice for less than a year.

During that time every known associate and contact was investigated to determine if they were in communication with him. Relentlessly, the forces of law and order were seeking to drive him out into the open.

Shapiro stated the FBI was hunting him wherever he went and under the circumstances it was like being in jail, thus he surrendered. On May 5, 1944, Shapiro was sentenced to 15 years to life after being found guilty of conspiracy and extortion.

His associate of many years, Louis “Lepke” Buchalter, was going to see how he made out, Shapiro related to special agents of the FBI, before he decided to surrender. Sixteen months later Buchalter followed suit, bringing to a close a manhunt that covered the continental United States and extended into Mexico, Costa Rica, Cuba, England, Canada, France, Puerto Rico, and Germany.

Over a period of years, the activities of this gang had been the subject of headline after headline in the metropolitan dailies. Industrial racketeers, never hesitant to enforce their mandates with lead pipes, stench bombs, brickbats and bullets, brutality and vandalism equaled that of the Huns of old. Millions of dollars were exacted as tribute by the paid enforcers of Shapiro and Buchalter. Both had a flair for organization, combined with considerable business acumen, rivaling that of big business and industrial executives. Their underworld empire extended from coast to coast. Associates occupied pinnacles of authority in various sections of the country, while others, hiding behind the garb of pseudo-respectability, nurtured their egos with their ill-gotten gains.

The FBI began inquiring into the racketeering tactics of Buchalter and Shapiro in 1932, which led to the indictment of 158 individuals by a federal grand jury in the Southern District of New York on November 6, 1933. The majority of the persons indicted subsequently entered pleas of guilty.

Combating The Rackets

The FBI first began landing blows on far-reaching, well-organized interstate rackets, through the penal provisions of the antitrust laws. Gradually, public resistance to racketeering stiffened as case after case was successfully prosecuted by the federal government, indicating that racketeering eventually could be combated once law enforcing agencies were armed, properly qualified, and divorced from the vagaries of political domination. Experience has demonstrated that no racket can long exist without:

- Political affiliation and protection;

- Terrified witnesses who, although willing to do their duty, are confronted with the fact that duty performed is meaningless and an open invitation to terrorism and brutal retaliation; and

- Lackadaisical, haphazard, inefficient, and apathetic law enforcement.

To invoke the federal antitrust laws the racketeering activity must be of such a character as to interfere with and restrain interstate commerce generally through the following methods:

- (a) Creation of monopolies, through the acquisition or merging of competing entities;

- (b) Maintenance of monopolies over competing entities with:price agreements;

- limitation of production by agreement;

- allocation of territories by agreement;

- maintenance of black lists;

- the establishment of retail prices through agreements with jobbers and dealers;

- furtherance of the above-mentioned items by agreements between trade associations; and

- agreements between labor unions and between labor unions which interfere with interstate commerce.

Each individual violation of the antitrust laws is punishable by a fine not to exceed $5,000 and imprisonment not to exceed one year. Ordinarily the big racketeering cases will involve several separate violations. Two cases are particularly significant as the forerunners to racketeering activities and which were to culminate in the smashing of the underworld empire created by Buchalter and Shapiro.

The Protective Fur Dressers Corporation and Fur Dressers Factor Corporation

The Protective Fur Dressers Corporation consisted of 17 of the largest rabbit skin dressing companies in the country. The membership of the Fur Dressers Factor Corporation was comprised of 46 of the largest dressers of furs other than rabbit skins. Both were created early in 1932.

The purposes and functions of these two combinations were to drive out of existence all non-member dressing firms; to persuade all dealers to deal exclusively with members of their combinations and prevent them from doing business with dealers who were non-members; to eliminate competition; to fix uniform prices by agreement; to set up a quota system whereby each of the different members received a certain percentage of the entire business handled by the members of the combination; to provide a credit system enforcing periodic statements; and effectively blacklisting any dealer who for any reason would not pay on settlement day. The objectives of this combination, naturally, were effected by intimidation and violence of the most vicious character directed toward both the dressers who would not join the combine and the dealers who insisted on doing business with non-members.

The fur dressers openly competed for business prior to the formation of these two corporations. The dealers and manufacturers could choose their own dressers. However, with the organization of the corporations, each of the dealers and manufacturers was notified of this formation and informed in no uncertain terms, by committees or individual members of the Corporation, that they would have to give all their business to a member firm to be designated by the Corporation for each order. They were also notified that, effective immediately, prices would be increased and all accounts would have to be settled in full each Friday. Naturally, some of the dealers and manufacturers continued to give a portion of their business to the independent dressers, some openly and others secretly. Often they would route the skins to one or more intermediate warehouses or have them hauled in private trucks. In nearly all instances, these shipments were detected by spotters for the Corporation. Then these individualistic dealers were the object of stronger solicitation for their business. This solicitation was frequently reiterated and emphasized through the medium of anonymous warnings over the telephone. If the calls did not have the desired effect, then the individualistic dealers were certain to be visited by strong-arm squads, armed with lead pipes and blackjacks. They became the victims of personal assaults or their goods became the targets of corrosive acids or stench bombs which were thrown into their plants. Usually these tactics brought the recalcitrant dealers into line and the Corporation had no further trouble from them.

The independent fur dressing establishments in some instances were ordered to get out of business. The orders were followed by explosive bombs. An investigation conducted by the FBI revealed that Buchalter and Shapiro furnished the strong-arm squads and directed their campaigns of depredation and violence, for both the Protective Fur Dressers Corporation and the Fur Dressers Factor Corporation. Buchalter and Shapiro had little contact with the members of the combine, ordinarily their contacts were limited to one key member in each group.

Buchalter and Shapiro had reached the position in life where they could depend upon hired thugs to do their dirty work for them. In the Fur Dressers Factor Corporation the contact was with its general manager, Abraham Beckerman, who had formerly been the manager of a joint council of the Amalgamated Clothing Workers of America, where he had made the acquaintanceship of Shapiro and Buchalter. Prior to his association with the Fur Dressers Factor Corporation, he had never been in the fur business. Samuel Mittelman was the president of the Protective Fur Dressers Corporation. He was also president of the Queens Fur Dressing Company.

The individual members of the Protective, when it was first organized, standardized the price for dressing the cheapest rabbit skins at five cents each. Later the price was raised until no skin was dressed for less than seven cents, with prices ranging up to 10 cents. It was established by the investigation that the Protective controlled from 80 to 90 percent of the business in 1932 and approximately 50 percent in 1933. It is estimated that 10,103,827 skins were dressed during the last eight months of 1932, and 8,541,255 of the skins were handled by members of the Protective. In 1933, the members of the Protective dressed 10,736,874 of the 22,127,740 skins handled.

Shapiro and Buchalter became active in the fur industry in April 1932 and continued their activities until the summer of 1933.

In April 1932, they were contacted by Abraham Beckerman, who had just become general manager of the Fur Dressers Factor Corporation and the Associated Employers of Fur Workers, Inc. “For about one and one-half years previously,” Beckerman told agents of the FBI, “I had been personally acquainted with Louis Buchalter, alias 'Lepke,' and with Jacob Shapiro, alias 'Gurrah,' and, accordingly, I called one of them on the telephone and went up to see them. I explained that there was a certain amount of organization work, meaning rough stuff, that would have to be done and inquired whether they were in a position to undertake it . . . They told me that they would take care of me.”

Beckerman then informed them that prior to his association with the Fur Dressers Factor Corporation this organization had entered into an arrangement for the employment of muscle men to enforce the mandates of the combination. The arrangement had been made with Jerry Sullivan, a lieutenant of the Owney Madden gang. Subsequently, the organization decided they had made a mistake and accordingly, had asked Beckerman to get him out.

Beckerman then related to FBI agents that in conference with Buchalter and Shapiro, “They said they thought that Jerry Sullivan would probably give a lot of trouble—that they didn't think I could handle him but that they themselves would try to straighten the matter out with Sullivan some other way. A few days later, I met both Buchalter and Shapiro again in a hotel and they told me that they had straightened the matter out with Jerry Sullivan by agreeing to pay him a certain proportion of the first money which was to be paid to them by me. If they had not undertaken to eliminate Sullivan from the picture, I should not have undertaken the job because it would have meant that I myself would have gotten in trouble. So far as the pay which Buchalter and Shapiro were to receive was concerned, they stated that they would start working on a piecework basis but that afterwards they would want to work steady and be paid on an annual basis. When I first talked to them, I explained that there would be different special jobs. At this first meeting, Buchalter and Shapiro suggested that they would expect to receive about $50,000 a year. As a matter of fact, after Buchalter and Shapiro started to work for us, they were not paid on either a piecework basis or on an annual basis, but they were paid in varying amounts from time to time whenever the funds were available. Usually they were paid about $2,000 or $2,500 at a time. The total amount which was paid them for this violence from the Fur Dressers Factor Corporation was approximately $30,000. This money was paid to them in two ways: first, by over-payments which were made by the Fur Dressers Factor Corporation to the National Fur Skin Dressing Company, Inc. and second, by direct payments from the Fur Dressers Factor Corporation.”

Shapiro and Buchalter were informed by the contact men as to which fur dressers, dealers, manufacturers, and union officials were not cooperating with the combination. Then these two saw to it that their men subjected the recalcitrant individuals to the intimidation, coercion, and violence necessary to bringing them in line. In all, there were more than 50 anonymous telephone threats, 12 assaults, four stench bombings, 10 explosive bombings, one kidnapping, three acid throwings, and two cases of arson included in the special service which Buchalter and Shapiro rendered to the two combinations. A similar program, of course, was carried on in behalf of the Protective Fur Dressers Corporation. Shapiro and Buchalter, as previously indicated, did not personally participate in any of these acts but directed their operations like generals behind the scenes. Shapiro, the cruder of the two, who has been likened by some of his associates to a "bull in a china shop," did stumble over the scenery on one occasion when in a discussion with Irving Potash, then secretary of the Needle Trade Workers Industrial Union, fur department, said "Potash, you'll have to deal with me, whether you like it or not."

The Needle Trade Workers Industrial Union was known at the time as the left wing, while the Lamb and Rabbit Workers Union was known as the right wing, the latter union later becoming an amalgamation of the two organizations who employed the services of Buchalter and Shapiro. The Needle Trade Workers Industrial Union had as its objectives (in 1932 and 1933) the complete unionization of shops of fur manufacturers, dressers, and dyers. Naturally, some conflict was bound to arise between the Protective and the Needle Trade Workers. Then too, the Associated Fur Trimmers and Coat Manufacturers, Inc., advocated its members employ only duly signed members of the American Federation of Labor, thus bringing this Association into direct conflict with the Needle Trade Workers. The following statement of one manufacturer reflects the terrorism that was typical of the unrest and strife that existed at that time:

"We are fur manufacturers and employ on the average from six to eight workers. On the fifteenth day of February 1933, at about one o'clock, a man walked into our place and said he was a worker and was sent to us by a man by the name of . . . We asked him what kind of work he wants to do and he said he was an operator. I thought it was very strange that he should come to us at that time. He looked rather suspicious and he looked all round the place and acted strange, but we paid no attention to him and he walked out.

About twenty minutes or a half hour afterwards, ten strange men walked into our place of business. One man walked straight to the telephone; another man stood by the door in the showroom and four men walked into the factory. We had at that time about five workers working. Another man walked to myself and my partner with his hand in his right-hand pocket, pointed at us as if there was a gun in it. Both myself and my partner were at the table standing up cutting and this man said, 'put down your knives and walk into the stock room quietly and don't make any noise' and at that time he was pointing his hand at us, although it was in his pocket, as if he had a gun in it. We couldn't understand, but we did as we were instructed. Then the rest of the men went into the shop to the workers and took from them all the tools and then they started with the tools to cut up all the skins that they were working on. Every skin that they could see and garments that we made were cut up into pieces and then they took some acid and threw it upon the skins. All of this we saw them do. They even left the bottle that contained the acid in the place.

The workers were chased in with us into a stockroom and this man with, presumably, a gun in his pocket, said 'you better stay quiet and not make any noise if you know what's good for you,' and he said 'remember not to say anything about what we did here, for if you should recognize us and point us out at any time, we will come up and finish you.' After they destroyed everything in our place, the leader ordered his fellows to walk towards the stairs and he told us to stay quietly for about five minutes until they got away, for if we did not, they would come up and hammer us to pieces and he said, 'if you say anything, you know what is waiting for you' and then he went away.”

“. . . I got in touch with the Communist leader and I asked him what he meant by sending people to destroy my merchandise. He came up to see me about four days after that and he said he was sorry that it was done but that he was in court and didn't know anything about it. I told him that this is a dastardly thing for him to do and I am not going to keep quiet about it and he said, 'if you do have any of the union people arrested, you will have the union around your neck.' I told him that the union people did not do that but it was a lot of gangsters with guns and knives and that I certainly could not afford to lose the damage that they have done. I asked him what his reason was to send such people up to me. What did I do to have him send such gangsters to my place and all he said was that 'if you are quiet about it, they won't come again and you will be able to work in peace.' He said he was going to make good for the machinery and merchandise but they never did.

I did nothing to justify the workers or any gangsters to come up and destroy my place. The gangsters that visited me, I am sure, are not fur workers. They looked and acted just like a lot of gangsters. Every machine was broken, so that we couldn't work and every piece of merchandise was cut up and acid spilled on it.”

The following incident is also typical of the operations of the Protective. This incident has also been summarized in the press. Mr. Joseph Joseph, of J. Joseph, Inc., New York City, had been doing a million dollars worth of business a year since 1918, by importing rabbit skins from Australia and New Zealand.

He first encountered difficulties in the fur business in the summer of 1932 when the Protective Fur Dressers Corporation was organized. At the time the Protective was formed, Mr. Joseph was giving some of his work to the Waverly Fur Dressing Company, in Newark, New Jersey, which he continued to do until that place was bombed. He had also received several communications from the Protective. On May 14, 1933, while he was at home, sitting on a bench, an unknown individual approached him at about 11 a.m., and without saying anything, tore off a newspaper which he had wrapped around a bottle of acid and threw the acid into Mr. Joseph's face, stating, “Now you've got it.” Mr. Joseph was unable to apprehend his assailant, who was able to make a getaway by jumping into a car driven by a confederate.

Mr. Joseph was considerably burned by the acid and his face was seriously scarred.

On May 17, 1933, Mr. Joseph received a telephone call, during which the following conversation took place:

Man: “Is this Joseph?”

Joseph: “Yes, who is this?”

Man: “A friend of yours. You got burned with acid.”

Joseph: “I know it.”

Man: “That comes from the Protective. The next is . . .”

Joseph: “Who are you?”

Man: “Goodbye.”

With reference to the Waverly Fur Dressing Company, Newark, New Jersey, which plant was bombed in the Spring of 1932, investigation revealed that this concern was experiencing no trouble whatsoever and, at the time, negotiations were pending whereby the Waverly Fur Dressing Company was to join the Protective Fur Dressers Factor Corporation. The Waverly Company did all its operations for one customer, handling approximately 30,000 skins a week. Under the agreement whereby it was to become affiliated with the Protective, it was to be limited to the handling of 15,000 skins a week. Because of this arrangement, the Waverly Company had withheld the actual consummation of the agreement to join. Shortly thereafter, two individuals who were identified as members of the Zwillman gang in Newark, appeared at the office of the Waverly plant and informed the manager that he had better join the Association. Later, they repeated their visit and urged the manager to call Mr. Balk, of the Protective Fur Dressers Corporation, and advise him they would join.

On the afternoon of the day the bombing took place, these individuals had again called at the Waverly plant and informed them in no uncertain terms that they had better call Mr. Balk and join right away. This was not done and that night a bomb was thrown into the window of the Waverly Company, resulting in considerable damage. The Strand Fur Dressing Company, a fancy dressing shop which occupied half of the ground floor and all the second floor of the building occupied by the Waverly Company, was also bombed. The two individuals who had called were immediately arrested and charged with the bombing and the Secretary of the Protective Fur Dressers Corporation was arrested as a material witness.

On April 24, 1933, hirelings of Shapiro and Buchalter staged an armed attack on the headquarters of the Needle Trade Workers Industrial Union. During this attack, two men were killed and many injured. Several of the attackers were so badly injured that they were unable to escape. On November 1, 1933, they were prosecuted and convicted of felonious assault in the state courts. One defendant jumped his bail of $10,000, which was forfeited.

Investigation into this instance of mob violence reflected that a few days before April 24, 1933, a large group of men met at a hotel suite maintained by the gang. They were told to raid the left wing headquarters and break up the meeting. Everyone seemed to know that they were working for Buchalter and Shapiro. These individuals were furnished with iron pipes wrapped in newspapers and some were armed with guns. There were between 20 and 30 in the group.

After leaving the hotel they separated into two groups, one squad proceeded by way of Seventh Avenue and the other by Eighth Avenue, meeting in front of the headquarters of the Needle Trade Workers at 131 West 28th Street. There they rushed the meeting and despite their iron pipes, although they did succeed in breaking up the meeting, the two squads of hoodlums came out second best. This incident revealed that Buchalter and Shapiro's headquarters were maintained in the hotel where the gangsters had met and where they had a credit account, known as the "Solomon" account. It appeared that whenever anyone came to the hotel and said they were with "Solomon" a room would be given them and the clerk would usually sign the register himself.

Morris Langer was in charge of the organizational activities of the fur workers for the Needle Trade Workers Industrial Union. In February 1933, he attended a conference between representatives of the Needle Trade Workers Industrial Union and the Protective Fur Dressers Corporation. At this time a representative of the Protective stated that three shops would have to be put out of business if the Protective was to control prices; that the Needle Trade Workers Industrial Union would have to cooperate. This they refused to do because the three shops were union shops, whereupon a representative of the Protective took representatives of the Needle Trade Workers Union aside and stated they should withdraw the workers from these shops or they would have to close, otherwise they would bomb the place and make the union pay the expense. On this occasion Morris Langer spoke very strongly against the Protective and within a month, on March 23, 1933, Langer was killed , as the result of a bomb having been placed in the hood of his automobile, after having in the meantime received many threats.

At a subsequent meeting, a representative of the Protective referred to one bombing which was unsuccessful and again stated the Needle Trade Workers Union must withdraw its men to put the shops out of business and this time the representative of the Protective insinuated by his statements that Langer had been put out of the way because he was stubborn and then the representative of the Protective gloated over the fact "that 'Lepke' and 'Gurrah' were back of their organization."

Prosecutive Action Against the Protective And Fur Dressers Factor Corporation

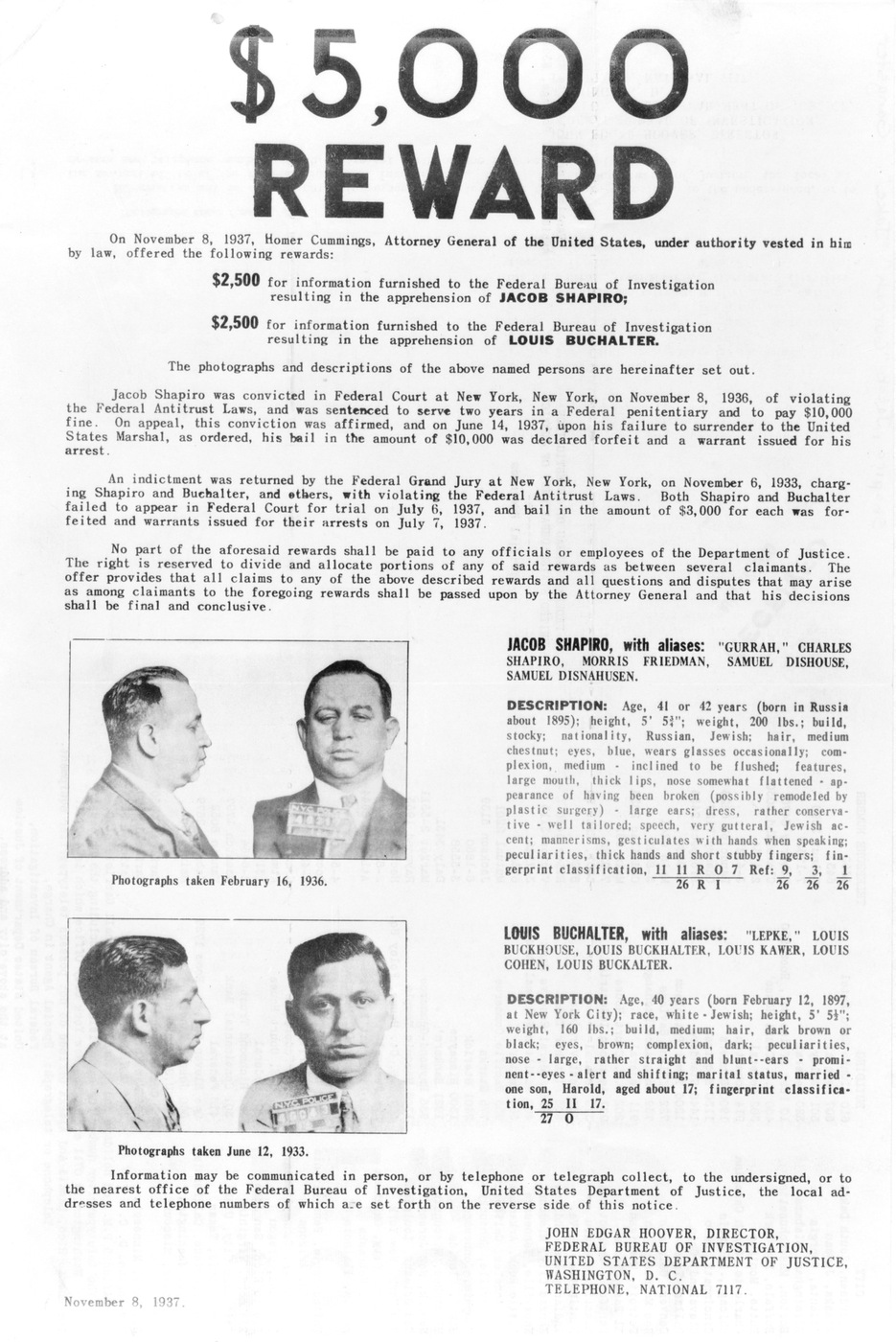

On November 6, 1933, the federal grand jury returned two indictments, each in four counts, one charging the Protective Fur Dressers Corporation and 33 individuals and corporations and the other charging the Fur Dressers Factor Corporation and 94 individuals and corporations with violating the Sherman Antitrust Act. Both Shapiro and Buchalter were named as defendants in these indictments.

On November 8, 1936, following the trial of the Protective Fur Dressers Corporation, Shapiro and Buchalter were convicted on all four counts and on November 12, 1936, each received sentences of two years imprisonment and fines of $10,000. On December 3, 1936, both Buchalter and Shapiro were released upon $10,000 cash bond, pending appeal.

On March 8, 1937, the judgement against Shapiro was affirmed, while Buchalter's conviction was reversed by the Circuit Court of Appeals. On June 5, 1937, the United States Supreme Court denied Shapiro's application for review and on June 14, 1937, he failed to surrender to the United States marshal, whereupon a bench warrant was issued for his arrest and his bail of $10,000 was forfeited on June 15, 1937.

On July 6, 1937, when the case of the Fur Dressers Factor Corporation and others was called for trial, Shapiro and Buchalter failed to appear and their bails, in the amount of $3,000 each, were ordered forfeited. Bench warrants were issued and Buchalter and Shapiro were declared to be fugitives. On September 28, 1936, 17 defendants entered pleas of guilty. On October 16, 1936, six additional defendants entered pleas of guilty, and on October 26, 1936, an indictment against two defendants was dismissed.

In the Fur Dressers Factor Corporation case, 52 defendants entered pleas of guilty on November 8, 1937, and on December 16, 1937, after a trial before United States District Judge John C. Knox, New York City, nine defendants were found guilty.

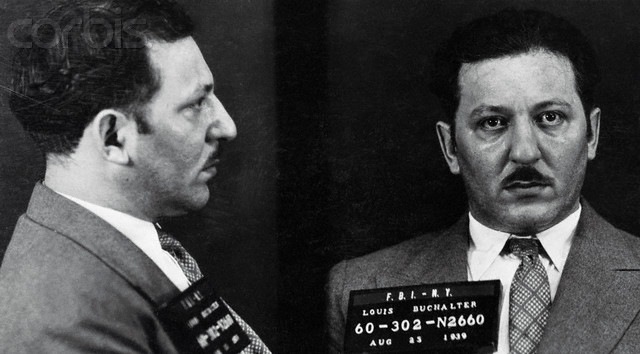

Shortly after he surrendered on August 24, 1939, Louis Buchalter was sentenced to prison on antitrust and narcotics charges. He was later tried and convicted on a state charge of murder. On March 4, 1944, he was executed at Sing Sing Prison.

Mobster Louis "Lepke" Buchalter (center) is escorted from a courthouse in 1940. Library of Congress photograph.