Charles Ross Kidnapping

One evening in late September 1937, Charles S. Ross, the wealthy president of a greeting card company, was driving towards Chicago when he was pulled over and kidnapped at gunpoint by a pair of criminals.

The ensuing investigation quickly became one of the largest for the young FBI.

It did not end well for Ross, who was murdered on October 10 (along with one of the criminals) after a fight broke out between the two kidnappers.

It didn’t end well for the mastermind of the plot, either. John Henry Seadlund, who had a long history of run-ins with the law, crisscrossed the country after obtaining $50,000 in ransom money but was ultimately tracked to Los Angeles using serial numbers from the bills. Agents posed as cashiers at a local racetrack where the ransom money had been used and arrested Ross on January 10, 1938 after he tried to place a bet with one of the bills. Seadlund confessed to the kidnapping and murders.

Seadlund’s Story

John Henry Seadlund, characterized as a cold-blooded and ruthless kidnapper and murderer, as well as a lone bank bandit, counted off the last 24 hours of his life on July 13, 1938, at Chicago, Illinois. On the early morning of July 14, 1938, Seadlund was executed in the electric chair for the abduction and murder of Charles Sherman Ross.

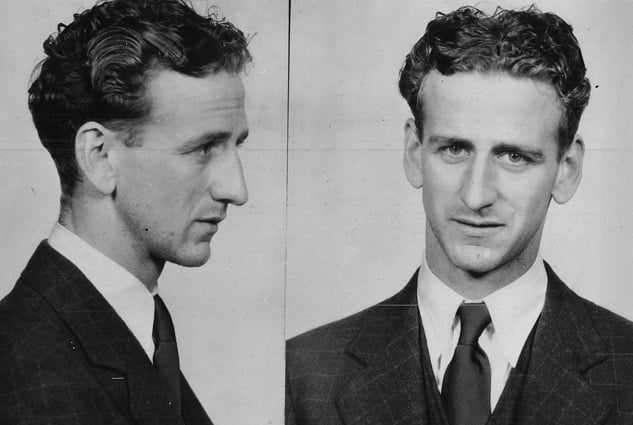

John Henry Seadlund

The date of his death was exactly 13 days prior to the day upon which he would have celebrated his 28th birthday, as John Henry Seadlund was born on July 27, 1910.

On October 19, 1937, when it was evident that the victim of this crime was not to be returned by his abductors, the FBI began to unravel the carefully woven web surrounding the crime committed by Seadlund. Every available resource at the command of the FBI was thrown into action to assist in the solution of the crime, which, according to Seadlund’s own statement, he deemed “a perfect crime.”

For almost four months, each clue was looked at to identify and locate the individual responsible for the crime. The wide ramifications of the investigative activities of the FBI reached beyond the territorial limits of the continental United States. Thus was conducted one of the most widespread and intensive manhunts ever engaged in by the FBI, utilizing the most modern means of scientific crime detection.

The pursuit of the FBI was maintained until Seadlund was located and apprehended as the result of a carefully planned trap set into operation by special agents under the direct personal supervision of Director Hoover at the Santa Anita Race Track near Los Angeles, California on January 14, 1938.

The resolution of this kidnapping revealed that there is no honor among criminals in their associations with their own kind. James Atwood Gray, one of the abductors, was apparently killed to avoid splitting the $50,000 ransom. It appears that Seadlund believed that by destroying the only living witnesses of this crime, he would destroy every link by which his detection might be possible. However, his uncontrollable desire to gamble at the race track resulted in his detection, location, and apprehension.

The Abduction

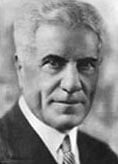

On the evening of Saturday, September 25, 1937, Charles Sherman Ross (right) drove his big sedan down North Avenue towards Chicago, Illinois.

On the evening of Saturday, September 25, 1937, Charles Sherman Ross (right) drove his big sedan down North Avenue towards Chicago, Illinois.

On the seat beside him was his former secretary and lifetime friend, Miss Florence Freihage. The gray-haired, 72-year-old retired president of the George S. Carrington Greeting Card Manufacturing Company of Chicago, Illinois, headed for Grand Avenue just south of the Chicago suburb of Franklin Park. “The car behind has been following us for some time and displaying unusually bright lights,” Ross stated. His voice indicated that he was noticeably alarmed. “I don’t like the looks of this. I’ll cut over to the side and let him pass.” Ross swung his car over to the side of the road, and the other car veered sharply in front, blocking it from going forward.

Seadlund promptly jumped out with a revolver in his hand and, after quickly walking over to the Ross car, he tried to open the door beside the driver’s seat but it was locked. Seadlund tapped the revolver against the glass of the door of the car and threatened to shoot Ross if he did not immediately open the door. Ross complied and, after being quickly searched, was forced into the abductor’s car that was being driven by James Atwood Gray. Seadlund explained in a commanding voice, “This is a kidnapping,” and curtly said, “My boss told me to bring you along.”

Miss Freihage protested, explaining that Ross had a weak heart and other ailments. Miss Freihage observed that Seadlund’s hair was curly and his face pointed and that he seemed youthful and nervous. After Seadlund looked Miss Freihage over suspiciously, he said in a barking voice, “What are you, his daughter or his sweetheart?” She replied, “No, I am just a friend.” Seadlund pressed the gun into Freihage’s shoulder and asked her, “How much can he give us—a half a million—a quarter of a million?” She replied that she did not know and pleaded with Seadlund not to take Ross away and offered him the money she had with her. Seadlund took $85 from her purse and ordered her to lie on the floor of the Ross automobile while he and Gray drove off in the kidnap car with Ross. Before departing, Seadlund warned: “Don’t call the police after we have gone or we’ll kill him.”

Miss Freihage complied with the demands of Seadlund, cringing with fear on the front seat of the Ross automobile, until she heard the kidnapper’s car race away into the darkness of the night. Then, looking up cautiously, she observed the red rear light of the kidnapper’s car moving in the darkness and attempted to follow it. The kidnap car outdistanced her, and she stopped at the first available telephone to call the police. Thus began what for almost four months was the Ross kidnapping mystery.

The Ransom Letters

With Ross carefully guarded and safely out of the reach of any alarm which might have been circulated for them, the kidnappers proceeded into Wisconsin and across into Minnesota, whereby late Sunday they reached the hideout near Emily, Minnesota. There in the woods was a cold, dark dugout that had been skillfully prepared by Seadlund and Gray to further their criminal enterprises.

John Henry Seadlund immediately set into motion the negotiations for the payment of the ransom by dictating a letter for Ross to write. However, Ross refused to ask for more than $5,000 ransom. Seadlund took the letter, studied it, and, seeing where he could change it to $50, 000, did so. He then took the ransom letter south and mailed it, thereafter moving into Chicago, Illinois.

The first ransom extortion letter was received on September 30, 1937. It was transmitted to Harvey S. Brackett, a former business associate of Ross at Green Bay, Wisconsin, through the U.S. mails in violation of the federal extortion statute. The letter read as follows:

Dear Dick

I am held for ransom. I have stated I am worth $100,000.00 including the G.S. Carrington Co. stock held in escrow by First National Bank try and raise $50,000.00

Yours

Charles S. Ross

Contact Harvey S. Brackett. Say nothing to anyone except Harvey. All communications will be addressed to Williams Bay

It is apparent from the above letter that it was intended to be mailed to Mrs. Charles S. Ross as “Dick” was the affectionate term with which Ross greeted his wife. However, to keep the ransom negotiations secret, it was forwarded by Seadlund with the following letter addressed to Harvey S. Brackett.

Dear Harvey S. Brackett

Have payment ready on instant notice, to be delivered by employee of Harley Davidson Co. on motorcycle. road to be designated later Rider to drop bag on highway at signal a shot, or repeated flashes of light. Rider to then continue forward for 300 yards and turn off Road on left side. To continue farther would be fatal. Money to be contained in small leather bag of following denomination.

20%

payment value

in $5.00

50%

$10.00

30%

in $20.00

All money to be non consecutive and unmarked and of authentic origin. When ready insert following add in Chicago Tribune used cars for sale dept.

Dodge. Good cond. No defect. (amount)

(over)

amount ready

(example $500.00 for $50,000.00)

$25.00 for $2,500.00)

Name of Rider

and address

Harvey you are to hire a motorcycle rider from Harley

Davidson Co. and get name and address Say nothing to anyone

except Dick.

Your friend

Charles S. Ross

for Abie

This letter was postmarked September 29, 1937, at Savanna, Illinois and was in the handwriting of Ross. An advertisement was placed in the indicated Chicago newspaper in conformity with the instructions of the kidnapper.

This letter was postmarked September 29, 1937, at Savanna, Illinois and was in the handwriting of Ross. An advertisement was placed in the indicated Chicago newspaper in conformity with the instructions of the kidnapper.

Seadlund, upon being assured of the compliance with his demands for the payment of the ransom, returned to the hideout near Emily, Minnesota, where he took photographs of Ross holding in front of him an October 2, 1937, late edition of a Chicago, Illinois newspaper (see image). He did this to show the well-being of Ross as of that date, thus establishing the authenticity of the ransom negotiations.

Seadlund then returned to Chicago, Illinois, where he purchased a typewriter and set in motion what he believed to be an ingenious scheme for the payment of the ransom demanded. He prepared three additional ransom extortion communications.

The second ransom extortion letter was postmarked at Chicago, Illinois, on October 2, 1937, addressed to Mr. Olden C. Armitage, a lodge associate of Ross, and read as follows:

Mr. Armitage:

Please keep this confidential – YOU – are Chas. s. Ross’ last hope His own choice as middleman. Somehow contact Mrs. Ross using A third person or some other devious means At any cost dont let the feds. suspect your part.

Raise the $50,000 asked without using her name if possible She to sighn notes for that amount her accounts are watched. ALL money to be bank-run, nonconsecutive, unmarked, and of authentic origin. I,ooo-20s 2000 each of Ios and 5s, place in small locked zipper bag.

Call Canel 3542 to obtain man to deliver payment on motorcycle. must dress in white, no sidecar, equipe for 500mi trip no danger if directions followed. hold ready at your office instant notice.

CONCLUSIVE PROOF OF ROSS’ wellbeing will be tendered before payment. locate secrete photodeveloper.

Run this ad. when note received.

-R–- used autos. for sale dept. exam. and tribune Auburn 33-good cond.no defects, (amount raised- thus $500.meaning $50,000 or $250 for $25,000) add only name and address of man hired to ride cycle.

Expect no contact before Wed.This note nullifies all previous attempts at contract if it fails no others will be attempted. Non genuine without this signature ALBIE – not brady”

This note ignored the prior letter and made a similar demand for ransom, the placing of an advertisement in a Chicago paper and a motorcycle rider to deliver the ransom. Canal 3542 was determined to be the telephone number of a motorcycle agency in Chicago, Illinois and thus it designated another motorcycle agency as a place to obtain the rider and indicated proof of Ross’ well-being, apparently to be furnished by a picture. Enclosed with this ransom letter was a small piece of paper apparently cut from the front of an envelope on which appeared the wording, “Mrs. Ross, 2912 Commonwealth Ave., Chicago, Ill.” in the handwriting of Charles S. Ross himself. An advertisement was placed in the designated Chicago newspaper in conformity with the instructions of the kidnapper.

The third ransom extortion letter, postmarked October 6, 1937, from Chicago, Illinois, was again addressed to Elton C. Armitage and read as follows:

ARMITAGE:

PROOF AT 230 SO.WABASH. RECEIPT NO. IO437. LEFT BY ELSON C ARMITAGE 6300 W HUNT. ROSS VERY INCENCED OVER DELAYS CAUSED BY ‘PIED PIPERS’ AND THEIR ‘RAT’ HUNTS. THREATENS REPERCUSIONS. ELABORATE PLAN OF COLLECTION PRAC. COMPLETE. BOUND TO FAIL IF SUSPISION AROUSDED_ONLY_ONE CONTACT WILL BE TRIED. BEND PIC. OF RIVER IF COP IN VIC. RIDER ‘OK’ DRESSWARMLEY? AT SIGNAL, A SHOT, DROP BAG ON RAOD CONTINUE 300yds and SHOVE CYCLE OVER LEFT BANK WALK IN SAM E

DIRECTION UNTIL ACCOSTED DONT HOLD HANDS UP OR TRY GOING THRU. ROSS DELIVERED SOON AS MONEY EXCHANGED.24...48 HRS. MAP OF ROUTE AND TIME OF START SENT SOON AS FULL AMOUNT READY DONT PUT UNDER TIME LOCK AS ‘REVERE’ TO START ½ HR AFTER MESSAGE RECEIVED. ‘ONE BY LAND AND TWO_IN_SEA’ IF DOUBLECROSSED.

ALBIE (NOT BRADY)

This letter indicated that proof of the victim’s well-being could be obtained at 230 South Wabash Street. It was discovered that this was an address of a camera company and that receipt #10437 was for films left in the name of Elton C. Armitage. Ten films were obtained from this company that had been developed and showed eight poses of Ross holding in front of him the October 2, 1937 football edition of a Chicago newspaper apparently taken in the daylight in a thicket containing birch trees.

Ross was dressed in the same clothes that he wore when he was kidnapped. This letter indicated that Ross would be held from 24 to 48 hours in order to exchange the ransom money of $50,000 demanded. Enclosed with this letter was Ross’ membership card for a commercial association dated January 9, 1902 on the back of which appeared the signature of Ross. Also enclosed was the automobile registration card of 1937 for Ross. In compliance with the instructions of the kidnapper, an advertisement was placed in the designated Chicago newspaper.

The fourth ransom extortion letter was received on October 8, 1937, postmarked at Chicago, Illinois, October 7, 1937, addressed to Elton C. Armitage, and read as follows:

EVERYTHING SET. LETS GO.

CONTACT MAN TO LEAVE TOWNS AT TIME FOLLOWING EACH POINT. START OAK PARK ON HIGH. NO. 20 AT 6:00pm FRI.ROCKFORD 8.45)- FREEPORT 9.40)-JUNCTION WITH HIGH. NO.80II.09)-SAVANNA II.59)-FULTON 12.30 am)-CORDOVA I.I0)-EAST MOLINE I.45)- GENESEO 2.I0)-SHEFFEILD 2.59 PRINCETON 3.25)-LA SALLE 4.05- OTTAWA 6.OOam JOLIET 7.05)-TAKE HIGH.66 TO CHI.

TRAVEL 50 mph GAS AS OFTEN AS SCHEDULE PERMITS EAT OTTAWA. TIE BAG SO CAN BE RELEASED INSTANTLY ON SIGNAL FLASHING OF LIGHTS OR SHOT DONT GO FURTHER THAN 300 YDS from SIGNAL WITHOUT DITCHING CYCLE CONTINUE AT WALK IN SAME DIRECTION ON HIGH. WILL HAVE REPORTS ON PROGRESS DONT TAG OTHER VEACLES IF POSSIBLE. KNOW YOU BY WHITE CLOTHING. ROSS WONT SHOW IF THIS CONTACT FAILS ON YOUR END. IF NEW DIRECTIONS GIVEN SOMEWHERE ON ROUTE ??? FOLLOW IF SIGHNED ALBIE.

INABILITY TO RAISE QUITE TOTAL AMOUNT MIGHT BE OVERLOOKED IF ACCOMPAIED BY ADDEQATE EXPLANATIONS. THE RUNAROUND OR A SUSPISCIOUS CAR OR TRUCK WONT.

ALBIE ((((NOT BRADY))))

PS

ROSS OPINES AS HOW THERES TOO MUCH VITAMIN G INTHIS MESS

WE AGREE

DICK: BE HOME SUN MORN HIDE THE SILVERWARE UNTIL ASSOCIATIONS WEAR OFF.

This letter gave detailed information of 14 places covering the distance of approximately 395 miles over which the motorcycle rider should travel leaving Oak Park, Illinois, at 6 p.m., October 8, 1937. “Vitamin G” in this letter, according to Seadlund, referred to special agents of the FBI.

The last three ransom extortion letters received in the Ross kidnapping case were all typewritten by John Henry Seadlund.

The pay-off was arranged by the Ross family in strict accordance with the instructions of the kidnappers. The motorcycle rider left Oak Park, Illinois, at 6 p.m., October 8, 1937 and arrived at a point about six miles east of Rockford, Illinois, on Highway #20, at 7:50 p.m., where he was contacted by Seadlund, who drove in behind him on the highway and flashed the lights of his automobile. This was the designated signal for the motorcycle rider to pay the $50,000 ransom and the kidnappers’ instructions were immediately complied with.

The money was thrown off the side of the road, and then the motorcycle rider ditched the motorcycle about 300 yards from this location, proceeding on foot pursuant to the instructions of the kidnappers. Seadlund picked up the ransom money and thereafter returned over a circuitous route, to the hideout at Emily, Minnesota, arriving there sometime on October 9, 1937. The ransom money at this point was divided, $30,000 being Seadlund’s share, while James Atwood Gray received the remaining $20,000.

The Murders

On the night of October 9, 1937, Seadlund, together with Gray, left in Seadlund’s automobile, together with Charles S. Ross, to the hideout approximately 17 miles northwest of Spooner, Wisconsin. They arrived at the hideout at 7 a.m., October 10, 1937.

At this point Seadlund claims he believed Gray was about to attack him, and they struggled. All three—Seadlund, Gray, and Ross—fell into the pit. In falling, according to Seadlund, he shot Gray while Ross was knocked out by the fall. Believing Gray could not recover, Seadlund emptied his gun into Gray’s body, killing him.

Then not being able to revive Ross, and to make certain he was dead, Seadlund shot him through the head. The body of Gray was already in the pit and Ross’ body was also placed therein. Seadlund closed the trap door and covered the pit over with dirt and brush. This occurred about 3 p.m. on October 10, 1937.

James Atwood Gray

At about 5 p.m., October 10, 1937, Seadlund then proceeded in the automobile, and a short distance north of Walker, Minnesota, to the east of Highway 371, he buried the typewriter box, which had previously contained the typewriter used in writing the last three ransom letters, in which Seadlund had concealed $32,645, all of which he believed was ransom money.

Thereafter, he proceeded to Omaha, Nebraska and other points in the Midwest, then to Spokane, Washington. At Spokane, on November 2, 1937, he disposed of the automobile used in the kidnapping, and he picked up another sedan that was later recovered in his possession at Los Angeles, California, January 14, 1938. He then proceeded east to various points, including Chicago; New York; Philadelphia; Washington, D.C.; Miami; Tropical Park, Miami, Florida; New Orleans; and Fairgrounds Race Track, New Orleans; Denver; Pecos, Texas; and then to Los Angeles, arriving there January 10, 1938.

During these trips he passed various bills of the ransom money in order to exchange this money.

Tracking the Ransom Money

On October 18, 1937, Mrs. Ross released a message to the kidnappers for the return of her husband, warning that if they did not return him, “All law enforcement officers would make vigorous efforts to locate and punish those responsible.” The next day, no word having been received from the kidnappers, the ransom lists prepared by the FBI, containing the serial numbers of the bills comprising the $50,000 ransom were forwarded to all available sources throughout the entire nation with the request that everyone be on the lookout for any of the bills bearing serial numbers contained in the ransom list.

Shortly thereafter the ransom money was identified in scattered sections of the United States. Each identification was carefully and meticulously investigated by the FBI in order to trace the source and to determine the modus operandi employed in changing this ransom money. In this way the trail of the kidnapper was followed step by step as the ransom bills were being turned in by public-spirited citizens to whom the FBI had supplied lists of the serial numbers of the bills in the $50,000 ransom package given to Seadlund on the evening of October 8, 1937.

In the early part of January 1938, upon the disclosure that ransom bills were being identified at the Federal Reserve Bank, the Bank of America at Los Angeles, California, Director Hoover immediately made plans to go to Los Angeles, California, so that he might personally direct the investigation. This ransom money was traced to the Santa Anita race track near Los Angeles, California.

Director Hoover ordered a trap to be set at the Santa Anita race track and, with the cooperation of the track officials, FBI agents were placed behind betting wickets as “change carriers,” ready to check each suspected bill against the ransom list. Other agents waited nearby and watched for the prearranged signal to close in on everyone identified as passing a Ross ransom bill.

The checking of the serial numbers was not an easy task, because of the speed with which bets were being made. The difficulty is best reflected in that at the Santa Anita track there were 500 pari-mutual ticket sellers and five hundred cashiers on the day this surveillance was placed in effect. From $400,000 to a million dollars daily was passing through the pari-mutual windows at this race track. The agents made the best of the situation, keeping a patient watch for the betters who would try to pass a ransom bill on the counter.

Capture and Confession

The vigil proved worthwhile when on January 14, 1938, a man walked up to the betting window, requested a ticket on a certain horse in the third race, and produced in payment a bill which, on quick inspection by an agent, proved to be a part of the ransom money paid in vain for the safe return of Ross. At a prearranged signal, special agents closed in on the man, who was in fact Seadlund, without causing any commotion and rushed him to the Los Angeles Field Office of the FBI.

The sum of $14,512.18 was found in this man’s possession, part of which was on his person, in his automobile, and at his hotel room in Los Angeles, California. Of this money $5,620 was found to be the Ross ransom money. This $14,521.18 recovered included $18.80 obtained on winning tickets held by Seadlund in connection with the races. The individual who gave his name as “Peter Ander,” but whose real name was John Henry Seadlund, a former logger in the Pacific Northwest, was not overcome by the sudden turn of events or by the mass of damaging evidence against him, but coolly and calmly denied his guilt of the Ross abduction to Director Hoover. He claimed he had obtained the money from known bank robber acquaintances, at a large reduction, indicating that he knew the money he had in his possession was the fruits of crime.

He denied any participation whatsoever in the Charles S. Ross kidnapping case until he was questioned at length by Director Hoover, and then John Henry Seadlund made a complete confession that consisted of a 28-page signed statement in which were included details of his life of crime, his admission of his participation in the Charles S. Ross kidnapping , as well as the killing of Ross and his own accomplice, James Atwood Gray.

Subsequent to the complete confession on January 17, 1938, Seadlund was flown to Minnesota where FBI agents planned a trip into the snow-covered lands of north woods. There, Seadlund admitted he had secretly buried the two murdered men, as well as a typewriter case full of ransom money.

The typewriter case and ransom money recovered by FBI agents

This was a hunt, not for the living, as in other manhunts, but for the dead, bullet-ridden bodies hidden in the woods by John Henry Seadlund. In this search, FBI agents dug up a $32,645 ransom cache, found the kidnapper’s underground hideout, and the dugout that contained the bodies of Charles S. Ross and Seadlund’s accomplice, James Atwood Gray.

Seadlund would point to the markers by which they would know the way—a road sign pierced by bullet holes and other trail markers. When the group could continue no farther by car because of snow, they proceeded over the fields and through the woods on foot. In a clump of trees, near a deserted stretch of railroad track, Seadlund pointed to a small pile of snow. When this was brushed away there was found a typewriter case packed with $32,645 of the Ross ransom money. This recovery brought the total obtained from Seadlund to $47,766.18, including a $600 automobile.

The group then moved onward towards Emily, Minnesota, through the woods and snow until Seadlund pointed to a snow-covered pile of brush and said, “the first hide-out.” The agents pulled aside the tree branches and exposed a dugout lined with wood in which Seadlund and Gray had kept Ross for nearly two weeks immediately following his abduction. Seadlund said that he and Gray had transferred Ross to the second dugout near Spooner, Wisconsin, where he had left Ross and Gray with bullets in their bodies. Horses and sleds were hired for the remainder of the expedition, for Seadlund warned that the trail led for miles through heavy snow drifts and through troughs and wooded territory. The party set out early in the morning of January 20, 1938.

In the underground “death chamber” partly concealed by the snow and brush the agents saw proof of Seadlund’s amazing confession. The nude body of Gray lay face downward on the floor of the cave. The body of Ross lay nearby. It was here that Seadlund suddenly made a desperate break for freedom after identifying the bodies. He stepped back toward the agents to whom he was chained and brought his handcuffs down over the agent’s head, and the pair fell in the snow. Seadlund swung his shackles, knocking his captor to the ground. He was quickly subdued and promptly apologized.

On January 20, 1938, Seadlund was returned to St. Paul, Minnesota, and on January 22, 1938, was removed to Chicago, Illinois. On January 24 he was arraigned before a U.S. commissioner at Chicago, Illinois, charged in complaint with having kidnaped Charles S. Ross and then transporting him from Franklin Park, Illinois to the vicinity of Emily, Minnesota. He was also charged with having collected $50,000 ransom six miles east of Rockford, Illinois, on October 8, 1937, and thereafter transporting, on or about October 9 or 10, 1937, the victim Charles S. Ross from the vicinity of Emily, Minnesota, to a point northwest of Spooner, Wisconsin, where, on or about October 10, 1937, he killed Charles S. Ross and his partner, James Atwood Gray. Seadlund stood silent and a plea of not guilty was entered for him. He was held without bail.

On February 1, 1938, an indictment was returned against John Henry Seadlund by the federal grand jury sitting in Chicago, Illinois, for violation of the federal kidnapping statute based upon the complaint mentioned previously. On February 2, 1938, Seadlund was brought before the United States district judge when counsel was appointed to represent Seadlund as an indigent prisoner.

On February 28, 1938, Seadlund entered a plea of guilty in the United States District Court to the above indictment and on March 16, 1938, was found guilty by a jury with recommendation of the death penalty. The United States district judge at Chicago, Illinois, on March 19, 1938, remanded Seadlund to the custody of the United States marshal to be electrocuted on April 19, 1938.

When the sentence was imposed, the defense immediately advised the United States District Court of their intention to appeal the case to the United States Circuit Court. On June 16, 1938, this court confirmed the decision of the United States District Court and pursuant to a mandate of the United States Circuit Court of Appeals, dated July 7, 1938, the trial court set the date of Seadlund’s execution for July 14, 1938, when he was electrocuted at Chicago, Illinois.

Chronicle

The investigation radiated from Chicago, where the kidnapping occurred, and the following chronicle of events reflects the wide geographical ramifications of the case.

- September 25, 1937: Charles Sherman Ross is kidnapped by John Henry Seadlund and James Atwood Gray at Franklin Park, Cook County, Illinois.

- September 26, 1937: The abductors arrive at the first hide-out near Emily, Minnesota.

- September 28, 1937: Seadland returns to Chicago where he begins to negotiate for the payment of $50,000 in ransom. The kidnapper mails four ransom letters in and around Chicago.

- October 8, 1937: A total of $50,000 is paid to Seadlund outside of Rockford, Illinois, according to instructions. Seadlund then returns to the first hide-out where Gray was keeping watch over the victim.

- October 10, 1937: The kidnappers and victim arrive at the second hide-out northwest of Spooner, Wisconsin. At about 3:00 p.m. Seadlund kills his partner Gray and Ross the victim. He then throws both bodies into a pit and covers them over with dirt and brush.

- October 17, 1937: Seadlund arrives near Walker, Minnesota, on highway 371 where he buries a portable typewriter box containing $32,625 of the ransom money.

- October 20, 1937: Seadlund arrives in Denver, Colorado, where he purchases a wire-haired terrier dog that he uses as a companion in his future travels.

- October 30, 1937: Seadlund arrives in Spokane, Washington, where he disposes of the Ford car used in the kidnapping and purchases an Oldsmobile car, returning to Chicago, Illinois.

- December 1, 1937: Seadlund arrives in New York City, where he stated that about $7,000 of the ransom money was stolen from his automobile.

- December 16, 1937: Seadlund arrives in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

- December 24, 1937: Seadlund arrives in Miami, Florida.

- January 2, 1938: Seadlund arrives in New Orleans, Louisiana.

- January 8, 1938: Seadlund arrives in Pecos, Texas, on his way to Los Angeles, California.

- January 10, 1938: Seadlund arrives in Los Angeles, California. He spends the next four days at a local race track where he is apprehended by FBI agents.

- January 17, 1938: Seadlund is transported to St. Paul, Minnesota, and on January 19, 1938, he points out the ransom cache at Walker, Minnesota. The next day he is transported by automobile to Spooner, Wisconsin, where he points out the death chamber.

- March 19, 1938: Seadlund is sentenced to death (Seadlund had pleaded guilty and the jury recommended death by electrocution).

Background on Seadlund

John Henry Seadlund was born on July 27, 1910, at Fenco, Wisconsin, and his family moved to Ironton, Minnesota, when he was an infant. His father, Paul Seadlund, died on March 23, 1933, and prior to his death was a master mechanic in various iron mines in the vicinity of Ironton, Minnesota.

Seadlund was interested in outdoor life and obtained his first gun, a .22 rifle, when he was 10 years of age, and often went into the woods with other boys to hunt. As he grew older he became interested in buying a larger rifle. Seadlund would often go into the Minnesota woods near Ironton and remain for several days on hunting trips. After he turned 14 there was very seldom a season passed that he did not kill at least one deer. He was apparently fond of hunting ducks and on his hunting expeditions would kill as many as 40 ducks, although the law limited the possession of ducks for one hunter to eight. He would never bring more than the legal limit of eight ducks home, but would hide the remainder in the alley and distribute them among the neighbors.

As a boy he was interested in mechanics and spent hours of his time fooling with motors and various mechanical airplanes and reading books and articles on aviation. As a student in high school he made average grades and never appeared to take his high school work seriously, but seemed to be more interested in reading outside literature. He never took a great interest in high school sports, but was known for ice hockey and played this game with a local team. He was good enough at hockey that he was offered an opportunity to play on a professional team and also was invited by the coaches from teachers’ colleges in the vicinity of Ironton, Minnesota to attend school and play on the hockey team of the school.

He graduated from the local grade school in Ironton, Minnesota and graduated from the Crosby-Ironton High School in 1928. Following his graduation, he went to work in the iron mines, working particularly in the blacksmith shops and machine shops under the supervision of his father. He appeared to be content with this type of work and worked regularly until July 1929, when, because of the Depression, he was laid off and the mines were practically closed. In July 1929, he left home and worked various jobs in Chicago, Illinois.

Seadlund remained at home from September 25, 1930 until May 30, 1934 and tried unsuccessfully to secure employment in the iron mines, which at that time were practically shut down. Unable to find employment there, he secured parttime employment at a filling station in Ironton, Minnesota and for a few months prior to May 30, 1934, acted as a delivery boy for a grocery store in Ironton, Minnesota.

John Henry Seadlund’s father died as the result of an accident March 23, 1933. He was found dead of monoxide poisoning in the family car.

Shortly after this, Seadlund came into contact with Tommy Carroll, a gangster, who was a member of the Dillinger gang and was subsequently killed at Waterloo, Iowa on June 7, 1934. Carroll was hiding in the woods and met Seadlund one day while Seadlund was hunting. Carroll convinced Seadlund to help him by bringing him food, and the two struck up an acquaintanceship. What Tommy Carroll told Seadlund is not known, but Seadlund was thrilled by his contact with Carroll, who, to him, was a “big shot” gangster.

On July 18, 1934, Seadlund robbed the Van Restaurant in Brainerd, Minnesota, walking away with $48. He was identified, arrested, and confined in the Crow Wing County jail at Brainerd, Minnesota, but escaped July 28, 1934, before he was brought to trial. He did not return to his home, but traveled to various parts of the country. When questioned by Director Hoover regarding the restaurant robbery, he claimed to have returned to this restaurant and eaten a meal there for the thrill of it, well knowing he was wanted and had been positively identified.

On March 1, 1935, Seadlund stole an automobile in Memphis, Tennessee, and transported it to Tuscaloosa, Alabama in violation of the National Motor Vehicle Theft Act, for which offense he was indicted on June 14, 1935, at Birmingham, Alabama under the name of Clarence Johnson. Thus John Henry Seadlund, like other notorious gangsters such as John Dillinger, was first sought by the FBI for the violation of the National Motor Vehicle Theft Act.

In 1936, Seadlund became more active and daring. On May 22, 1936, he robbed the State Bank of Centuria at Milltown, Wisconsin while armed and obtained $1,039. He said that while he was hitchhiking near Fond du Lac, Wisconsin, he was picked up by a girl, whose name will not be given, and that he traveled as far as Bismarck, North Dakota, with her, but became disgusted as she was engaged in prostitution.

Seadlund left her and stole her car, using it when he robbed the First National Bank at Eagle River, Wisconsin on June 15, 1936, where he obtained $1,737. He wrecked the car in making his getaway and was forced to abandon it and go into the woods on foot. FBI agents recovered valuable identifying evidence as a result of a search of this abandoned car and under scientific analysis by experts of the technical laboratory of the FBI, were able to identify Seadlund as being in possession of this getaway car and from the modus operandi employed in this bank robbery were able to show that he was the perpetrator of other bank robberies.

Seadlund was in the woods for about a week, evading apprehension and suffering greatly from hunger. He advised Director Hoover that he broke into a cabin and stole a .22 rifle with which he killed a rabbit and ate some of it raw since he did not have any matches with which to build a fire to cook it.

After having robbed the two banks, Seadlund then went to Spokane, Washington, bought a truck and went into the timber business. At one time he had as many as 10 men working for him, but he claimed not one of them was his friend. His nature did not draw others to him. Restlessness such seized him, and he left Washington in August 1936 and proceeded back to Wisconsin. On August 25, 1936, Seadlund robbed the Peoples State Bank at Colfax, Wisconsin, obtaining $2,408. Again he returned to the state of Washington and lived and worked near Lake Trout. Seadlund felt he had a reputation there and had established himself under the name of Peter Anders, and it was a long distance from the territory in which he had operated as a bank robber.

He again came east and robbed the First National Bank at Shakoppe, Minnesota and secured $4,700 on January 25, 1937. Again he scurried back to Spokane, Washington with the loot.

In June 1937, Seadlund again started back east with the intention of robbing the bank at Bloomer, Wisconsin. Someplace near Superior, Montana, he picked up a hitchhiker named James Atwood Gray, a young man who was about 20 years old. He asked to ride in the back seat of the car so he could sleep and found a gun between the seat and the upholstery. As Seadlund had done to the girl who befriended him, so Gray attempted to do to Seadlund. He held Seadlund up and took his money and was about to take Seadlund’s car when Seadlund surprised him and knocked him out. Again, Seadlund did the unexpected, and instead of leaving the boy, he forced him to drive the car, and after a few days, the two decided to work together.

Seadlund and Gray, while at Rhinelander, Wisconsin, planning the robbery of a bank at Minocqua, Wisconsin, obtained information concerning six or seven women who were traveling by truck and who were carrying a box that was supposed to contain valuable jewelry. The two held this truck up and obtained a box that they thought held the jewelry, and they took one woman from this truck as a hostage and released her after traveling four or five miles south of Rhinelander. When Seadlund and Gray opened this box, they were surprised it contained candy.

While at Lake Geneva, Wisconsin, on September 2, 1937, a cafe owner was pointed out to them as saving approximately $100,000 worth of “hot” jewelry. Seadlund and Gray followed him and his wife out on the road and held them up with a gun. The woman was seized as a victim. She was held until September 4, 1937 and released after they had failed to collect the ransom from her husband. This kidnapping was an interstate matter, and the FBI had no jurisdiction.

Seadlund and Gray then planned to kidnap a prominent merchant of Decatur, Illinois, and while Gray waited in the car, Seadlund went to his home with the intention of kidnapping him. However, when Seadlund learned that he was absent from the city this plan was given up. Seadlund told Director Hoover that he considered kidnapping Jerome H. “Dizzy” Dean, the baseball player, but abandoned this plan when he realized the ramifications that would be involved in forcing Dean’s ball club to pay a ransom.

John Henry Seadlund’s final criminal act was the kidnapping of Charles Sherman Ross on September 26, 1937 and the subsequent killing of Ross and James Atwood Gray. For these offenses, Seadlund was electrocuted in Chicago, Illinois on July 14, 1938, and he was laid to rest on July 17, 1938, in the Klondike Cemetery, two miles south of Ironton, Minnesota, beside the grave of his father.