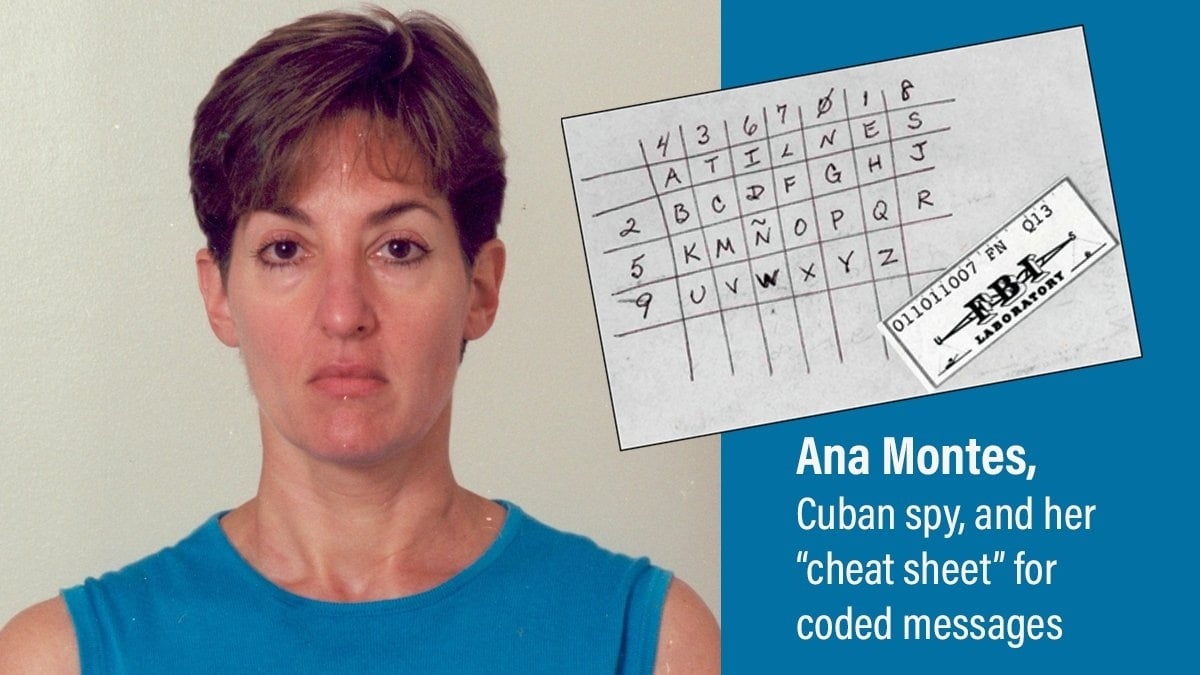

Ana Montes: Cuban Spy

Ana Montes used a "cheat sheet" provided by Cuban intelligence to help her encrypt and decrypt messages to and from her handlers.

Just 10 days after the attacks of 9/11, the FBI arrested a 44-year-old woman named Ana Belen Montes.

She had nothing to do with the terrorist strikes, but her arrest had everything to do with protecting the country at a time when national security was of paramount importance.

Montes, it turned out, was spying for the Cubans from inside the U.S. intelligence community itself—as a senior analyst with the Defense Intelligence Agency, or DIA. And she was soon to have access to classified information about America’s planned invasion of Afghanistan the following month.

Montes was actually the DIA’s top Cuban analyst and was known throughout the U.S. intelligence community for her expertise. Little did anyone know how much of an expert she had become and how much she was leaking classified U.S. military information and deliberately distorting the government’s views on Cuba.

It began as a classic tale of recruitment. In 1984, Montes held a clerical job at the Department of Justice in Washington. She often spoke openly against the U.S. government’s policies towards Central America. Soon, her opinions caught the attention of Cuban “officials” who thought she’d be sympathetic to their cause. She met with them. Soon after, Montes agreed to help Cuba.

She knew she needed a job inside the intelligence community to do that, so she applied at DIA, a key producer of intelligence for the Pentagon. By the time she started work there in 1985, she was a fully recruited spy.

To escape detection, Montes never removed any documents from work, electronically or in hard copy. Instead, she kept the details in her head and went home and typed them up on her laptop. Then, she transferred the information onto encrypted disks. After receiving instructions from the Cubans in code via short-wave radio, she’d meet with her handler and turn over the disks.

During her years at DIA, security officials learned about her foreign policy views and were concerned about her access to sensitive information, but they had no reason to believe she was sharing secrets. And she had passed a polygraph.

Her downfall began in 1996, when an astute DIA colleague—acting on a gut feeling—reported to a security official that he felt Montes might be under the influence of Cuban intelligence. The official interviewed her, but she admitted nothing.

The security officer filed the interview away until four years later, when he learned that the FBI was working to uncover an unidentified Cuban agent operating in Washington. He contacted the Bureau with his suspicions. After a careful review of the facts, the FBI opened an investigation.

Through physical and electronic surveillance and covert searches, the FBI was able to build a case against Montes. Agents also wanted to identify her Cuban handler and were waiting for a face-to-face meeting between the two of them, which is why they held off arresting her for some time. However, outside events overtook the investigation—as a result of the 9/11 attacks, Montes was about to be assigned work related to U.S. war plans. The Bureau and DIA didn’t want that to happen, so she was arrested.

What was Montes’ motivation for spying? Pure ideology—she disagreed with U.S. foreign policy. Montes accepted no money for passing classified information, except for reimbursements for some expenses.

Montes, who acknowledged revealing the identities of four American undercover intelligence officers working in Cuba, pled guilty in 2002 and was sentenced to 25 years in prison.