Color of Law

Agent Exposes Civil Rights Crimes in Alabama Prison

A view of the prison yard at the Ventress Correctional Facility in Alabama. The image was part of a display in court to show the perspectives of witnesses to the fatal 2010 assault of an inmate by corrections officers.

There was never any dispute that Rocrast Mack, a 24-year-old serving time on drug charges in a state prison in Alabama, died at the hands of corrections officers in 2010. What wasn’t immediately clear was how and why the inmate sustained a lethal beating.

What was known was this: On August 4, 2010, a female corrections officer confronted Mack in his bunk, accused him of inappropriate behavior, and struck him. Mack retaliated, the officer radioed for help, more officers arrived, and Mack was beaten in three separate prison locations over a 40-minute period. He died the next day from his injuries. Guards claimed Mack was fighting them throughout the ordeal and sustained his fatal injuries in a fall.

An investigator from Alabama’s State Bureau of Investigation thought the stories didn’t add up and called the FBI, which investigates cases of abuse of authority—or color of law—and other civil rights violations. When Special Agent Susan Hanson opened her case at the Ventress Correctional Facility, it was evident her biggest challenge would be getting to the truth.

“The injuries that caused Mack’s death did not match up with the story the corrections officers were telling,” said Hanson, who works in the Dothan Resident Agency, a satellite office of the FBI’s Mobile Division. Meanwhile, witness accounts were suspect, given the questionable reliability of the sources. “You could have 10 different inmates who were in the very same room and they would give you 10 different stories,” she added.

What did emerge was a portrait of a corrupt prison environment led by a heavy-handed guard—Lt. Michael Smith. Smith, the main subject in the investigation, held sway over corrections officers and inmates alike. A few guards privately acknowledged that Smith’s history of intimidation could eventually land him in hot water. For Hanson, who conducted hundreds of interviews over nearly three years, the key to cracking the case was to find a sympathetic guard whose conscience carried more weight than his fear of Smith.

“It really was working with one of the officers, spending a lot of time with him, and telling him that the story just doesn’t make sense. It cannot have happened that way,” Hanson said. The guard implicated Smith but never broke ranks from the original narrative—that their use of force was justified.

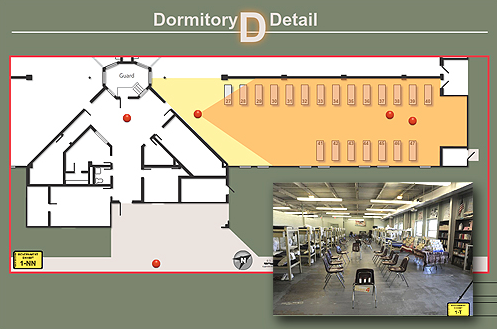

To build her case, Hanson and Special Agent William Beersdorf enlisted Mobile’s Evidence Response Team (ERT) to take extensive photographs from witnesses’ vantage points that could support or refute their claims. “That’s where she was able to start separating fact from fiction,” said Beersdorf. Specialists were brought in from the FBI’s Charlotte office to collect exact measurements and chart graphical representations of where each of the assaults occurred.

A display used during trial shows the layout of the dorm where the initial assault took place. The red dots show the positions of witnesses, and the inset image shows what they would have seen.

“Susan then could eliminate witnesses because of what they could or couldn’t see,” said Bryan Myers, an ERT technician who made six trips to the prison during the course of the investigation. The Special Projects Unit at FBI Headquarters assembled an interactive blueprint of the prison that showed everyone’s precise locations during the beatings. In the end, the evidence revealed how a cadre of guards, led by Smith, struck and kicked Mack so severely he died—and then conspired to cover it up.

“It was very helpful during trial,” said Hanson. Four officers were convicted last year on civil rights, obstruction of justice, and conspiracy charges and received prison terms—including Smith, who was sentenced to 30 years.

Hanson, who was named a finalist for the Service to America Medal by the Partnership for Public Service for bringing the guards to justice and exposing corruption in Alabama’s prisons, said the case is still heartbreaking to her because Mack was in the care of officials who had been bestowed a public trust.

“He was serving his time, he was not a problem child, and he was beaten to death because of conduct that had gotten out of control,” she said.

Resources:

- Civil Rights: Color of Law

- Partnership for Public Service: Susan Hanson profile