Terrorism 2002/2005

Terrorism 2002-2005

U.S. Department of Justice

Federal Bureau of Investigation

Since the mid-1980s, the FBI has published Terrorism in the United States, an unclassified annual report summarizing terrorist activities in this country. While this publication provided an overview of the terrorist threat in the United States and its territories, its limited scope proved inadequate for conveying either the breadth or width of the terrorist threat facing U.S. interests or the scale of the FBI’s response to terrorism worldwide. To better reflect the nature of the threat and the international scope of our response, the FBI expanded the focus of its annual terrorism report in the 2000/2001 edition to include discussion of FBI investigations overseas and renamed the series Terrorism.

This second edition of Terrorism provides an overview of the terrorist incidents and preventions designated by the FBI as having taken place in the United States and its territories during the years 2002 through 2005 and that are matters of public record. This publication does not include those incidents which the Bureau classifies under criminal rather than terrorism investigations. In addition, the report discusses major FBI investigations overseas and identifies significant events—including legislative actions, prosecutorial updates, and program developments—relevant to U.S. counterterrorism efforts. The report concludes with an “In Focus” article summarizing the history of the FBI’s counterterrorism program.

While the discussion of international terrorism provides a more complete overview of FBI terrorism investigations into acts involving U.S. interests around the world, Terrorism is not intended as a comprehensive annual review of worldwide terrorist activity. The chronological incidents, charts, and figures included in Terrorism 2002-2005 reflect only those incidents identified in the Terrorism/Terrorism in the United States series. For more complete listings of worldwide terrorist incidents, see the Worldwide Incidents Tracking System maintained by the National Counterterrorism Center at www.nctc.gov and the Terrorism Knowledge Base compiled by the Memorial Institute for the Prevention of Terrorism at www.tkb.org.

The FBI hopes you will find Terrorism 2002-2005 to be a helpful resource and thanks you for your interest in the FBI’s Counterterrorism Program. A full-text and graphics version of this issue, as well as recent back issues of Terrorism and Terrorism in the United States, are available for on-line reference on the FBI home page at www.fbi.gov.

Federal Bureau of Investigation

Counterterrorism Division

FBI Policy and Guidelines

In accordance with U.S. counterterrorism policy, the FBI considers terrorists to be criminals. FBI efforts in countering terrorist threats are multifaceted. Information obtained through FBI investigations is analyzed and used to prevent terrorist activity and, whenever possible, to effect the arrest and prosecution of potential perpetrators. FBI investigations are initiated in accordance with the following guidelines:

- Domestic terrorism investigations are conducted in accordance with The Attorney General’s Guidelines on General Crimes, Racketeering Enterprise, and Terrorism Enterprise Investigations. These guidelines set forth the predication threshold and limits for investigations of U.S. persons who reside in the United States, who are not acting on behalf of a foreign power, and who may be conducting criminal activities in support of terrorist objectives.

- International terrorism investigations are conducted in accordance with The Attorney General Guidelines for FBI Foreign Intelligence Collection and Foreign Counterintelligence Investigations. These guidelines set forth the predication level and limits for investigating U.S. persons or foreign nationals in the United States who are targeting national security interests on behalf of a foreign power.

Although various Executive Orders, Presidential Decision Directives, and congressional statutes address the issue of terrorism, there is no single federal law specifically making terrorism a crime. Terrorists are arrested and convicted under existing criminal statutes. All suspected terrorists placed under arrest are provided access to legal counsel and normal judicial procedure, including Fifth Amendment guarantees.

Definitions

There is no single, universally accepted, definition of terrorism. Terrorism is defined in the Code of Federal Regulations as “the unlawful use of force and violence against persons or property to intimidate or coerce a government, the civilian population, or any segment thereof, in furtherance of political or social objectives” (28 C.F.R. Section 0.85).

The FBI further describes terrorism as either domestic or international, depending on the origin, base, and objectives of the terrorist organization. For the purpose of this report, the FBI will use the following definitions:

- Domestic terrorism is the unlawful use, or threatened use, of force or violence by a group or individual based and operating entirely within the United States or Puerto Rico without foreign direction committed against persons or property to intimidate or coerce a government, the civilian population, or any segment thereof in furtherance of political or social objectives.

- International terrorism involves violent acts or acts dangerous to human life that are a violation of the criminal laws of the United States or any state, or that would be a criminal violation if committed within the jurisdiction of the United States or any state. These acts appear to be intended to intimidate or coerce a civilian population, influence the policy of a government by intimidation or coercion, or affect the conduct of a government by assassination or kidnapping. International terrorist acts occur outside the United States or transcend national boundaries in terms of the means by which they are accomplished, the persons they appear intended to coerce or intimidate, or the locale in which their perpetrators operate or seek asylum.

The FBI Divides Terrorist-Related Activities into Two Categories:

- A terrorist incident is a violent act or an act dangerous to human life, in violation of the criminal laws of the United States, or of any state, to intimidate or coerce a government, the civilian population, or any segment thereof, in furtherance of political or social objectives.

- A terrorism prevention is a documented instance in which a violent act by a known or suspected terrorist group or individual with the means and a proven propensity for violence is successfully interdicted through investigative activity.

Note: The FBI investigates terrorism-related matters without regard to race, religion, national origin, or gender. Reference to individual members of any political, ethnic, or religious group in this report is not meant to imply that all members of that group are terrorists. Terrorists represent a small criminal minority in any larger social context.

Introduction

This edition of Terrorism highlights significant terrorism-related events in the United States and selected FBI investigative efforts overseas that occurred during the years 2002 through 2005. Additionally, this report provides a wide range of statistical data relating to terrorism in the United States during the past two decades. This material is presented to provide readers with an historical framework for the examination of contemporary terrorism issues.

In keeping with a longstanding trend, domestic extremists carried out the majority of terrorist incidents during this period. Twenty three of the 24 recorded terrorist incidents were perpetrated by domestic terrorists. With the exception of a white supremacist’s firebombing of a synagogue in Oklahoma City, Oklahoma, all of the domestic terrorist incidents were committed by special interest extremists active in the animal rights and environmental movements. The acts committed by these extremists typically targeted materials and facilities rather than persons. The sole international terrorist incident in the United States recorded for this period involved an attack at the El Al ticket counter at Los Angeles International Airport, which claimed the lives of two victims.

The terrorism preventions for 2002 through 2005 present a more diverse threat picture. Eight of the 14 recorded terrorism preventions stemmed from right-wing extremism, and included disruptions to plotting by individuals involved with the militia, white supremacist, constitutionalist and tax protestor, and anti-abortion movements. The remaining preventions included disruptions to plotting by an anarchist in Bellingham, Washington, who sought to bomb a U.S. Coast Guard station; a plot to attack an Islamic center in Pinellis Park, Florida; and a plot by prison-originated, Muslim convert group to attack U.S. military, Jewish, and Israeli targets in the greater Los Angeles area. In addition, three preventions involved individuals who sought to provide material support to foreign terrorist organizations, including al-Qa’ida, for attacks within the United States.

Whereas the violent global jihadist movement manifested itself primarily in terrorism preventions in the United States from 2002 through 2005, internationally the movement claimed major attacks against U.S. and Western targets that resulted in American casualties. Most of these incidents were perpetrated by regional jihadist groups operating in primarily Muslim countries, and included attacks committed by Indonesia-based Jemaah Islamiya and al-Qa’ida in the Arabian Peninsula. The coordinated suicide bombing of London’s mass transit system by homegrown jihadists, however, brought the violent jihadist movement and the tactic of suicide bombing to a major European capital.

In addition to these incidents and preventions, the years 2002 through 2005 saw the resolutions to high-profile prosecutions in the fight against terrorism. These included the October 4, 2002, sentencing of John Walker Lindh to 20-years in prison for conspiring with the Taliban to kill U.S. citizens; the January 30, 2003, sentencing of Richard Colvin Reid to life in prison for attempting to bomb a transcontinental flight using a shoe bomb; the December 2003 sentencings of the Lackawanna Six terror cell members, who received prison terms ranging from seven to 10 years for providing material support or resources to al-Qa’ida; the sentencings in 2003 and 2004 of members of a Portland terrorist cell, who received prison terms ranging from three to 18 years for plotting to provide assistance to the Taliban and al-Qa’ida in fighting against U.S. troops in Afghanistan; the September 29, 2004, sentencing inYemeni court of six individuals for their roles in the USS Cole bombing, two of whom received the death penalty; the April 6, 2005, sentencing of Matthew Hale, leader of the white supremacist Creativity Movement, to 40 years in prison for solicitation of violence and obstruction of justice; the July 18, 2005, sentencing of Eric Robert Rudolph to life in prison for perpetrating several bombings, including the Centennial Olympic Park bombing in Atlanta, Georgia; the April 26, 2005, sentencing of Ali Al-Timimi to life in prison for encouraging others to receive military training from the designated foreign terrorist organization Lashkar-e-Tayyiba to fight U.S. troops in Afghanistan; and the August 30, 2005, sentencing of white supremacist Sean Michael Gillespie to 39 years for the synagogue firebombing in Oklahoma City.

FBI counterterrorism initiatives since the 9/11 terrorist attack have focused on preventing future attacks through the timely gathering, analysis, and dissemination of information; the facilitation of appropriate sharing of terrorism-related information between federal, state, and local partners; and the advancement of intelligence and law enforcement partnerships worldwide. FBI and U.S. counterterrorism organizational changes from 2002 through 2005 include the creation of the National Joint Terrorism Task Force; the establishment of the Foreign Terrorist Tracking Task Force; the consolidation of government terrorist watch lists into the Terrorist Screening Center; the creation of the U.S. Department of Homeland Security; and the restructuring of the U.S. Intelligence Community under the newly created Office of the Director of National Intelligence. These and other federal initiatives are discussed in greater detail in the concluding In Focus retrospective of the FBI’s counterterrorism program.

The FBI recorded seven domestic terrorist incidents, one international terrorist incident, and one terrorism prevention in 2002. The seven domestic terrorism incidents included a string of attacks over a period of several months claimed by special interest movements. These attacks are attributed either solely to the Earth Liberation Front (ELF), an extremist environmental movement active in the United States during the past 20 years, or jointly to the ELF and the Animal Liberation Front, an extremist animal rights movement that has carried out numerous terrorist attacks since 1987. The international terrorist incident involved fatal shootings at the El Al ticket counter at Los Angeles International Airport.

In the one terrorism prevention, law enforcement in Florida exposed a plot to attack Islamic facilities in the United States in response to international events, including the September 11 attacks.

Two deaths resulted from terrorist activity carried out in the United States in 2002.

A major international terrorist incident during 2002 involved the October 12 bombing of the Kuta Beach nightclub area on Bali, Indonesia. The attack, carried out by the Jemaah Islamiya, a terrorist organization active in Southeast Asia, resulted in 202 deaths, including those of seven Americans.

March 2002 – November 2002

Vandalism and Arson

Erie, Harborcreek, and Warren, Pennsylvania

(Six acts of Domestic Terrorism)

Between March 2002 and November 2002, a series of animal rights and ecoterrorism incidents occurred in Erie, Harborcreek, and Warren, Pennsylvania. On March 18, 2002, Pennsylvania State Police discovered heavy equipment used to clear trees at a construction site in Erie, Pennsylvania, spray painted with the statements “ELF, in the protection of mother earth,” and “Stop Deforestation.” On March 24, 2002, police responded to the same construction site, where a large hydraulic crane had been set on fire, causing approximately $500,000 in damage. A facsimile, purportedly from ELF, claimed responsibility for the arson and vandalism. ELF also claimed responsibility for an August 11, 2002, arson on the U.S. Forestry Scientific Laboratory in Warren, Pennsylvania. In separate incidents in May and September 2002, unknown subjects released approximately 250 mink from a fur farm in Harborcreek, Pennsylvania. On November 26, 2002, the barn on the same Harborcreek fur farm was destroyed by arson. On the ELF Web site, ELF and ALF jointly claimed responsibility for these mink releases and the arson. On August 11, 2002, unknown individuals committed arson on the U.S. Forestry Scientific Laboratory in Warren, Pennsylvania.

In separate incidents in May and September 2002, unknown subjects released approximately 250 mink from a fur farm in Harborcreek, Pennsylvania. On November 26, 2002, the barn on the same Harborcreek fur farm was destroyed by arson. On the ELF Web site, ELF and ALF jointly claimed responsibility for these mink releases and the arson. On August 11, 2002, unknown individuals committed arson on the U.S. Forestry Scientific Laboratory in Warren, Pennsylvania.

July 4, 2002

Attack on El Al Ticket Counter in Los Angeles International Airport

Los Angeles, California

(One act of International Terrorism)

On July 4, 2002, Hesham Mohamed Ali Hedayat began shooting randomly while standing in line at the ticket counter of El Al Israeli National Airlines at the Los Angeles International Airport. During the attack, an El Al ticketing agent and a bystander were killed. Hedayat was subsequently killed by an El Al security officer. A worldwide investigation determined that Hadayat’s religious and political beliefs were the primary motivation for the attack, and not personal revenge. Following these investigative findings, this case was officially designated as an act of international terrorism.

August-October 2002

Vandalism and Destruction of Property

Henrico County, Virginia

Goochland County, Virginia

(One act of Domestic Terrorism)

During the period of August–November 2002, Aaron L. Linas, John B. Wade, and Adam V. Blackwell carried out several acts of vandalism and destruction of private property, in apparent acts of environmental terrorism. Many of these acts were attributed to the Earth Liberation Front (ELF).

On several days in August 2002, the individuals damaged 12 construction vehicles at a construction site in Goochland, Virginia, by pouring sugar into the gas tanks. The individuals also vandalized two homes under construction in the area, writing the word “sprawl” on one of the homes.

In September 2002, the individuals vandalized construction vehicles in Henrico County, Virginia, and attempted to burn a backhoe and construction crane. On September 28, 2002, 25 sport utility vehicles (SUVs) were damaged at an Henrico County Ford Dealership, including the etching of the letters “ELF” and “SUV” into some of the vehicles. Also in September, vandalism occurred at two fast food restaurants. A Jeep Liberty was also damaged, and the vandals left a note on the vehicle stating “SUVs are killing the world” and “Earth Liberation Front.”

In October of 2002, vandals claiming to be part of ELF apparently used an axe to damage three SUVs parked in the River Lake Colony subdivision of Henrico County, Virginia. Notes were left on all of the vehicles claiming the attack was an effort to raise environmental and political awareness.

Linas, Wade, and Blackwell pled guilty to conspiracy to commit these acts and were subsequently convicted and sentenced to three years and six months, three years and one month, and 10 months in federal prison, respectively, and ordered to divide the total restitution payment of $204,021.86 between them.

August 22, 2002

Planned Attack against Islamic Center of Pinellas County

Pinellas Park, Florida

(Prevention of one act of Domestic Terrorism)

On August 22, 2002, police in Pinellas County, Florida, responding to a domestic dispute detained Robert J. Goldstein after finding numerous weapons and explosives and a “mission statement” threatening to attack Islamic facilities in the United States. Goldstein was later arrested and charged with weapons violations and an attempt to destroy property. Michael Wallace Hardee, Samuel V. Shannahan III, and Goldstein’s wife, Kristi Goldstein, were also arrested and charged in connection with the plot. An investigation revealed that the intended target of Goldstein’s planned attack was the Islamic Center of Pinellas County, in Pinellas Park, Florida, and that the attack had been planned to coincide with the first anniversary of the September 11, 2001, terrorist attack. Investigators also determined that Goldstein intended to target the Islamic Center in perceived retaliation for Palestinian suicide bombings in Israel. The four pled guilty in the Middle District of Florida to their roles in the plotting, and in 2003 received federal prison sentences ranging from three years to Robert Goldstein’s 12 years and seven months.

January 19, 2002

Kathleen Ann Soliah Sentenced.

On January 19, 2002, Kathleen Ann Soliah was sentenced to two consecutive 10 years to life terms for her role in a 1975 car bombing plot associated with the Symbionese Liberation Army. On October 31, 2001, Soliah pled guilty to two counts related to the car bombing plot. Soliah remained a fugitive for 23 years until her arrest on June 16, 1999, when she was living under the alias Sara Jane Olsen.

March 14, 2002

Appeal Denied in the Pan Am 103 Bombing Case.

On March 14, 2002, an appeal filed by Abdel Basset Ali Al-Megrahi, seeking to overturn his conviction of bombing Pan Am flight 103 over Lockerbie, Scotland, was denied. Al-Megrahi had filed the appeal at the Scottish Court of Appeal in Camp Zeist, The Netherlands. Al-Megrahi was convicted on January 31, 2001, for the 1988 bombing, which killed the 259 passengers of the flight and 11 individuals on the ground. Al-Megrahi was sentenced to life in prison.

June 15, 2002

Donald Rudolph Sentenced for 1999 Propane Plot.

On June 15, 2002, Donald Rudolph was sentenced to five years in prison for his role in a plot to destroy a propane storage facility near Elk Grove, California. Rudolph had pled guilty on January 19, 2001, to withholding knowledge of a conspiracy to use a weapon of mass destruction in connection with the propane plot.

The plot to attack the propane storage facility was disrupted on December 3, 1999, when members of the Sacramento Joint Terrorism Task Force arrested Kevin Ray Patterson and Charles Dennis Kiles. Patterson, Kiles, and Rudolph were associated with an antigovernment group active in the central region of the state. When arrested, Patterson and Kiles were in possession of a detonation cord, blasting caps, grenade hulls, and various chemicals—including ammonium nitrate—and numerous weapons. Patterson and Kiles were convicted in May 2002 for conspiracy to use a weapon of mass destruction and conspiracy to use a destructive device.

October 12, 2002

Nightclub Bombing

Bali, Indonesia

On October 12, 2002, three bombs, including a large vehicle bomb and a possible suicide bomber, devastated a nightclub area at Kuta Beach on the Indonesian island of Bali. The blasts killed 202 people, including seven Americans, and injured as many as 350. Most of those killed and injured were foreign tourists. This bombing has been attributed to members of the Jemaah Islamiya (JI) terrorist organization, a Southeast Asian-based terrorist network with links to al-Qa’ida, which allegedly helped finance the attack. The Bali bombing may have been carried out in response to audiotaped appeals from al-Qa’ida leader Usama Bin Ladin and his senior deputy Ayman al-Zawahiri broadcast on the al-Jazeera network beginning on October 6, 2002, that urged renewed attacks on U.S. and Western interests.

The FBI joined several other international antiterror agencies to assist Indonesia in the investigation of the attack. The investigation has yielded approximately 30 convictions overseas; including three suspects sentenced to death after being convicted of planning and carrying out the bombing. Notable among the convictions is Muslim cleric Abu Bakar Bashir, who is suspected of being the spiritual leader of JI. Bashir was sentenced in March 2003 to 30 months in prison for his part in the criminal conspiracy leading to the attack, although he was cleared of charges of planning a terrorist attack.

Investigators believe JI militants Noordin Mohammad Top and bomb-maker Azahari Husin were the masterminds behind the Bali nightclub attacks and several other Southeast Asian terrorist attacks. Husin was killed by Indonesian police during a shootout on November 9, 2005, in East Java, Indonesia. Top remained a fugitive at the end of 2005.

On October 23, 2002, President George W. Bush designated JI as a Specially Designated Global Terrorist (SDGT) under Executive Order 13224. Investigation into the Bali bombing is ongoing.

June 21, 2002

Two Smugglers Convicted in Terror Financing Case

On June 21, 2002, Mohamad Hammoud and Chawki Hammoud were convicted for their roles in a Charlotte, North Carolina-based, cigarette smuggling ring with ties to terrorism financing. Both men were convicted of cigarette smuggling, money laundering, racketeering, and credit card fraud. Mohamad Hammoud was also convicted of providing financial support to Hizballah, a designated foreign terrorist organization believed to have received financing through Hammoud’s smuggling enterprise. Chawki Hammoud was not found guilty of Hizballah ties.

June 21, 2002

FBI Fly Team Established

On June 21, 2002, FBI Director Mueller announced the creation of the Fly Team in the Counterterrorism Division to enhance the Bureau’s capabilities in the areas of counterterrorism and intelligence collection. The Fly Team deploys rapidly and proactively worldwide on missions to identify and prevent acts of terrorism, respond to crisis incidents, and pursue the arrests and prosecutions of terrorists who have engaged in or aided and abetted those who engaged in acts of terrorism.

July 2002

Creation of National Joint Terrorism Task Force

In July of 2002, the National Joint Terrorism Task Force (NJTTF) was created by order of the Director of the FBI. The NJTTF, staffed by representatives from 40 federal, state, and local agencies, is tasked with coordinating the flow of information between its participating entities and the Joint Terrorism Task Forces (JTTFs) located in FBI field offices and resident agencies across the country.

October 4, 2002

John Walker Lindh Sentenced

On October 4, 2002, U.S. citizen John Walker Lindh was sentenced to 20 years in prison after pleading guilty in July to terrorism charges related to his association with the Taliban in Afghanistan. In February, a grand jury in the Eastern District of Virginia indicted Lindh on 10 counts, charging him as an al-Qa’ida-trained terrorist who conspired with the Taliban to kill U.S. citizens. In addition to criminal charges that had previously been levied against Lindh, the indictment added charges of conspiracy to contribute services to al-Qa’ida, contributing services to al-Qa’ida, conspiracy to supply services to the Taliban, and weapons charges.

November 25, 2002

Signing of the Homeland Security Act of 2002

On November 25, 2002, President Bush signed House Resolution 5005, the Homeland Security Act of 2002, officially establishing the U.S. Department of Homeland Security. The act combined various government agencies dealing with transportation, border, and other security issues from the U.S. Departments of Justice, Defense, Treasury, and Commerce into a single cabinet department, consolidating the U.S. government’s homeland security efforts.

In 2003, the FBI recorded six terrorist incidents and five terrorism preventions. Domestic terrorists, specifically animal rights and environmental extremists, were responsible for each of the six incidents. Three of the incidents were perpetrated by followers of the Earth Liberation Front extremist movement and involved acts of arson or vandalism and destruction of property. The other three incidents were perpetrated by extremists within the animal rights movement, and included and act of vandalism claimed by the Animal Liberation Front, and two bombings at businesses affiliated with Huntingdon Life Sciences, a frequent target of the extreme animal rights movement.

Each of the five preventions involved domestic terrorist organizations or extremists. These included a white supremacist in Pennsylvania, who planned attacks against abortion clinics and minority targets; a constitutionalist and tax protestor in Idaho, who attempted to arrange for the murders of federal persons involved in a tax evasion case against him; an individual in Texas associated with antigovernment militia members, who was found in possession of heavy weaponry, sodium cyanide, and plans to weaponize sodium cyanide; an anarchist, who planned to bomb a U.S. Coast Guard; and an anti-abortion extremist in Florida, who planned to bomb abortion clinics.

No deaths or serious injuries resulted from terrorist activity carried out in the United States in 2003.

Major international terrorist incidents involving U.S. casualties included two attacks stemming from the violent global jihadist movement. In Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, al-Qa’ida operatives conducted coordinated assaults on three residential compounds housing Western workers. Nine of the 35 people killed in the attack were Americans. In addition, Jemaah Islamiya bombed the JW Marriott Hotel in Jakarta, Indonesia. The attack resulted in 11 fatalities and 144 injuries, including injuries to two U.S. citizens.

January 1, 2003

Arson

Girard, Pennsylvania

(One act of Domestic Terrorism)

On January 1, 2003, an unknown individual(s) set two pickup trucks and one sport utility vehicle on fire at a car dealership in Girard, Pennsylvania, causing $96,000 in damages. This arson followed the series of environmental and animal rights extremist incidents in northwest Pennsylvania discussed in the preceding 2002 terrorist incidents section. ELF claimed responsibility for the arson.

March 3, 2003

Vandalism

Chico, California.

(One act of Domestic Terrorism)

On March 3, 2003, an unknown number of individuals placed two one-gallon jugs filled with kerosene near a McDonald’s restaurant in Chico, California, and vandalized the restaurant with graffiti. The graffiti included statements such as “Animal Liberation Front,” “Meat is Murder,” and “Species Equality.” Two communiques were discovered claiming responsibility for the attack. Robert Brooks and Harjit Singh Gill were convicted in the Eastern District of California for making false statements to a grand jury in connection with the attack, and, in June 2005, received sentences of a $500 fine and 36 months probation, respectively.

August 1, 2003

September 19, 2003

Arson

San Diego, California.

(One act of Domestic Terrorism)

On August 1, 2003, the San Diego Fire Department and San Diego Police Department responded to an arson fire at the Garden Condominium, a five-story, 206-unit condominium complex under construction in the University Town Center area of San Diego. The fire caused an estimated $20 million in damages to the building and surrounding construction equipment. Investigators found graffiti at the site implicating Earth Liberation Front (ELF) extremists with the incident, including the message “IF YOU BUILD IT – WE WILL BURN IT. THE ELF’S ARE MAD.

On September 19, 2003, two other new home sites were also set on fire, with similar messages left at the scene. The fires destroyed four homes and damaged two others, causing an estimated loss of $3 million. The August 1 and September 19 arson incidents remain under investigation.

|

May 12, 2003 On the evening of May 12, 2003, al-Qa’ida operatives assaulted three residential compounds in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, that house Western guest workers. At least fifteen assailants in six vehicles, two vehicles at each location participated in the attacks against the Al-Hamra Oasis Village, Jedawal compound, and Vinnell Company compound located in suburban Riyadh. After breaching manned security barriers at two of the three sites, the attackers detonated vehicle-borne improvised explosive devices (VBIEDs) in the compounds, killing 35 people, including nine Americans, and injuring nearly 200 others. This assault followed a string of al-Qa’ida operations, including the August 7, 1998, East African embassy bombings; the October 12, 2000, bombing of the USS Cole in Aden, Yemen; the September 11, 2001, attack in the United States; and attacks on November 28, 2002, carried out against primarily Israeli targets in Mombasa, Kenya, involving simultaneous attacks against multiple targets. The May 12 attack reflected a high degree of planning, pre-operational surveillance, and coordination among teams—traditional hallmarks of al-Qa’ida operations. It also reflected a highly refined approach to suicide bombings that may have incorporated lessons learned from the 1998 U.S. embassy bombings and other attacks. Preliminary investigation indicates that operatives traveling in lead vehicles attacked guards at each of the sites with small arms fire and hand grenades to quickly breach gates and other security measures to gain access to the compounds. Once inside the compounds, assailants may also have fired weapons to draw the attention of residents to window areas to maximize casualties. The FBI and foreign partners have identified approximately 30 individuals thought to be involved in the planning and execution of the attack. Nearly all of these individuals have been killed or arrested by Saudi security forces. |

|

August 5, 2003 On the afternoon of August 5, 2003, a vehicle-borne improvised explosive device (VBIED) exploded in front of the JW Marriott Hotel located in Mega Kuningan, South Jakarta, Indonesia. The blast killed 11 people, not including the suicide bomber, and injured 144 others, including two U.S. citizens. The blast caused extensive damage to the hotel and an adjacent office building. Investigation by the Indonesian National Police, the Australian Federal Police, and the FBI traced responsibility for the bombing to Jemaah Islamiyah (JI), a transnational Southeast Asian terrorist organization based in Indonesia with close links to al-Qa’ida, which helped to finance the bombing. The international investigation has identified over 30 individuals involved in the conspiracy to bomb the JW Marriott Hotel in Jakarta. Witness testimony has identified Noordin Mohammed Top as the leader of the operation and Dr. Azahari Husin as the bombmaker. Approximately 30 of the conspirators have been arrested, tried, and convicted in Indonesian courts and have received prison sentences ranging from three to 14 years. Husin was killed by Indonesian police during a shootout on November 9, 2005, in East Java, Indonesia. Top remained a fugitive at the end of 2005. The investigation into the bombing of the JW Marriott Hotel in Jakarta is ongoing. |

August 22, 2003

Vandalism and Destruction of Property

West Covina, California.

(One act of Domestic Terrorism)

On August 22, 2003, individuals associated with the Earth Liberation Front (ELF) carried out acts of vandalism in the Los Angeles, California, area, damaging roughly 125 vehicles and one commercial building. Much of the damage was caused by spray-painted graffiti, although in two cases, individuals set fire to sport utility vehicles (SUVs). Some of the graffiti associated SUVs with “terrorism.” On April 18, 2005, William Jensen Cottrell was sentenced to eight years and four months in federal prison and fined $3.5 million for the incident. Two other suspects in the attack—Tyler Johnson and Michie Oe—remained at large at the end of 2005.

August 28, 2003

Bombing

Emeryville, California

(One act of Domestic Terrorism)

On August 28, 2003, an improvised explosive device (IED) was detonated near the front door of Chiron Life Science Center in Emeryville, California, causing damage to the building. A second device detonated in another Chiron building shortly after first responders arrived at the scene, also damaging the building and the surrounding area. Chiron had previously received harassing e-mails, telephone calls, and faxes, and some Chiron employees had been harassed at their residences. Chiron, an animal testing laboratory, is associated with Huntingdon Life Sciences (HLS). HLS, and individuals and companies associated with it, have regularly been targeted by animal rights extremists. Daniel Andreas San Diego is suspected of having carried out the bombing and remained a fugitive at the end of 2005.

September 26, 2003

Bombing

Pleasanton, California.

(One act of Domestic Terrorism)

On September 26, 2003, an improvised explosive device was detonated at Shaklee Corporation in Pleasanton, California. Shaklee Corporation is a subsidiary of Yamanouchi Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd., which has been targeted by animal rights extremists in the past. Daniel Andreas San Diego is suspected of having carried out this bombing and the August 28, 2003, bombing at Chiron Life Science Center. San Diego remained a fugitive at the end of 2005.

February 13, 2003

Planned Attacks on Abortion Clinics and Minority Targets

Amwell Township, Pennsylvania.

(Prevention of one act of Domestic Terrorism)

On February 13, 2003, law enforcement officials arrested David Wayne Hull, a long-time member and self-professed leader of the White Knights of the Ku Klux Klan (KKK). Hull had been exploding pipe bombs on his property in Amwell Township, Pennsylvania, had built and detonated improvised explosive devices (IEDs) during KKK events, and was recorded instructing individuals on how to place IEDs to cause maximum damage. Hull had also made threats against minorities and abortion clinics. Hull was indicted in March 2003 for firearms charges, witness tampering, and instructing persons on procedures for creating destructive devices. A jury in the Western District of Pennsylvania convicted Hull on seven counts of the ten-count indictment. On February 25, 2005, Hull was sentenced to 12 years in prison, followed by three years of probation.

April 4, 2003

Planned Murder Plots against Federal Judge, AUSA, and IRS Agent

Grangeville, Idaho

(Prevention of one act of Domestic Terrorism)

On April 4, 2003, the FBI arrested David Roland Hinkson, a constitutionalist and tax protestor, for attempting to arrange the murders of a federal judge, an Assistant U.S. Attorney, and an IRS Agent whom he blamed for his legal problems regarding a tax evasion case against him. Between December 2002 and March 2003, Hinkson offered two individuals $10,000 for committing all three murders. On January 27, 2005, Hinkson was found guilty on three counts of solicitation to commit murder after a three week jury trial in Boise, Idaho. On June 3, 2005, Hinkson was sentenced to 43 years in federal prison.

April 10, 2003

Planned Cyanide Attack

Tyler, Texas

(Prevention of one act of Domestic Terrorism)

On April 10, 2003, the FBI arrested William Joseph Krar for fraud-related charges stemming from his attempt to deliver numerous false identification badges—including a United Nations Observer Badges, Defense Intelligence Agency identification, and a Federal Concealed Weapons Permit—to Edward Feltus, a member of the New Jersey Militia. Krar had also been identified as a potential weapons supplier associated with extremist militia activities. In a search of Krar’s Texas residence at the time of his arrest, FBI investigators found firearms, explosives, blasting caps, machine guns, over 100,000 rounds of ammunition, approximately 800 grams of sodium cyanide, and plans to weaponize the sodium cyanide. Krar and a co-conspirator, Judith Bruey, pled guilty to federal weapons charges, and in May 2004 were sentenced to 135 months and 57 months in federal custody, respectively. Feltus pled guilty to aiding and abetting the transportation of false IDs, and was sentenced in May 2004 to 18 months probation and fined $1,500.

June 9, 2003

Planned Bombing of a U.S. Coast Guard Facility

Bellingham, Washington

(Prevention of one act of Domestic Terrorism)

On June 9, 2003, the FBI arrested Paul Douglas Revak for plotting to bomb a U.S. Coast Guard facility in Bellingham, Washington. Revak, who had previously declared himself to be an anarchist, was reportedly attempting to precipitate a revolution in the United States and had discussed the targeting of several nearby military installations. Revak was arrested when he negotiated with an undercover FBI employee for the purchase of explosive device components. Under a plea agreement, Revak was charged with threatening to use a weapon of mass destruction and sentenced to five years’ probation.

November 11, 2003

Planned Bombings of Abortion Clinics

Miami, Florida

(Prevention of one act of Domestic Terrorism)

On November 11, 2003, Stephen John Jordi was arrested in Miami, Florida, for plotting to attack several abortion clinics. Jordi had openly discussed his intentions to attack abortion clinics, had expressed solidarity with anti-abortion extremists, and had associated with individuals from the anti-abortion extremist group Army of God. Jordi set out potential targets and a specific time frame for the attacks, and had cased and videotaped numerous Miami-area abortion clinics. He had also purchased several items to carry out the attack, including containers of gasoline and propane, flares, starting fluid, and a silencer purchased from an FBI source. Jordi was indicted on November 15, 2003, for attempting to damage and destroy property used in interstate commerce, distribution of information relating to the manufacture or use of explosive or destructive devices, and possession of a firearm that was not registered to him. On July 8, 2004, a federal judge in Miami sentenced Jordi to five years in prison.

January 30, 2003

Richard C. Reid Sentenced

On January 30, 2003, Richard Colvin Reid was sentenced to life in prison for his December 2001 attempt to bomb American Airlines flight 63 with an explosive device concealed in his shoe. Reid had been indicted on January 16, 2002, on nine terrorism-related counts, and pled guilty on October 4, 2002.

February 14, 2003

Kathleen Ann Soliah Sentenced

On February 14, 2003, Kathleen Ann Soliah, a former member of the Symbionese Liberation Army (SLA) serving time for her role in a 1975 car bombing plot, was sentenced for the 1975 murder of Myrna Opsahl. Soliah received six years added to the sentence she was already serving, after pleading guilty on November 7, 2002, for her role in the 1975 SLA bank robbery that killed Opsahl.

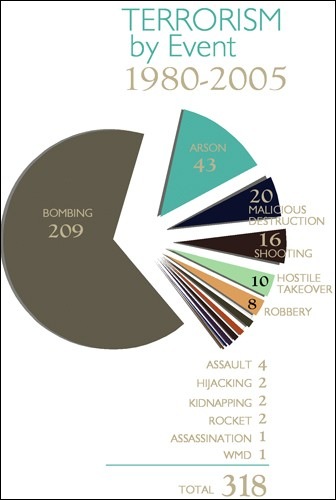

Terrorism by event 1980-2005 pie chart. The graphic of pie chart shows 318 total events broken into categories; 209 bombings, 43 Arsons 20 malicious destructions, 16 shootings 10 hostile takeovers, 8 robberies, 4 assaults, 2 Hijackings, 2 Kidnappings, 2 rockets, 1 assassinanation and 1 WMD.

February 19, 2003

Arrests and Indictments of Palestinian Islamic Jihad Members

On February 19, 2003, four members of the Palestinian Islamic Jihad (PIJ) terrorist organization—Sami Amin al-Arian, Sameeh Hammoudeh, Hatim Naji Fariz, and Ghassan Zayed Ballut—were arrested and charged with operating a racketeering enterprise from 1984 to 2003 in support of violence. The indictment, which was unsealed on February 20, 2003, also charged the individuals with “conspiracy within the United States to kill and maim persons abroad, conspiracy to provide material support and resources to PIJ, conspiracy to violate emergency economic sanctions,” extortion, perjury, obstruction of justice, and immigration fraud. Four other individuals were also charged under the same indictment—Ramadan Abduallah Shallah, Bashir Musa Mohammed Nafi, Mohammed Tasir Hassan Al-Khatib, and Abd Al Aziz Awda—but were overseas and remained fugitives at the end of 2005.

February 28, 2003

Cigarette Smugglers Sentenced in Terror Financing Case

On February 28, 2003, Mohamad and Chawki Hammoud were sentenced to prison terms for their roles in a Charlotte, North Carolina-based, cigarette smuggling ring with ties to terrorist financing. Both men were convicted of cigarette smuggling, money laundering, racketeering, and credit card fraud. Mohamad Hammoud, who was found guilty of providing support to Hizballah in addition to smuggling charges, was given a maximum 155-year prison sentence. Chawki Hammoud, who was convicted in the smuggling case but was not found to have ties to Hizballah, was sentenced to 51 months in prison.

March 1, 2003

Capture of Khalid Shaykh Mohammed

On March 1, 2003, counterterrorism forces in Pakistan captured Khalid Shaykh Mohammed, an al-Qa’ida operational commander and the man believed to have been the mastermind of the September 11, 2001, attack. Shaykh Mohammed is also believed to have played a role in a number of other attacks and planned attacks, including the 2002 bombings in Bali, Indonesia, the 2000 bombing of the USS Cole in Yemen, and a 1995 plot to blow up multiple U.S. commercial airliners.

April 14, 2003

Plea Agreement for Earnest James Ujaama

On April 14, 2003, Earnest James Ujaama pled guilty in Seattle federal court to conspiring to provide goods and services to the Taliban in Afghanistan. As part of the plea agreement, federal prosecutors dropped charges alleging that Ujaama had plotted to establish a terrorist training camp in Bly, Oregon. In return, Ujaama was sentenced to 24 months in prison.

August 18, 2003

Sentencing of Enaam Arnaout

On August 18, 2003, Enaam Arnaout, the director of Benevolence International Foundation, was sentenced to 11 years in federal prison after pleading guilty on February 10, 2003, to terrorism-related racketeering conspiracy charges. Arnaout had been indicted on October 9, 2002, for conspiracy to fraudulently obtain charitable donations in order to provide financial assistance to al-Qa’ida and other organizations engaged in violence and terrorism. The indictment charged Arnaout with conspiracy to engage in racketeering, conspiracy to provide material support to terrorists, money laundering, mail fraud, and wire fraud in his attempt to fraudulently use the charitable contributions of Muslim Americans, U.S. corporations, and other donors to support terrorism overseas. Benevolence International Foundation was registered as a tax-exempt charitable organization; Arnaout allegedly used it as a racketeering enterprise.

August-December 2003

Plea Agreements and Sentencing for Portland Terror Cell Suspects

Between August and December 2003, six of seven members of a Portland, Oregon-based terrorist cell pled guilty to terrorism-related charges. The six were indicted in October 2002 for conspiracy to provide assistance to Taliban and al-Qa’ida forces by planning to travel to fight U.S. troops stationed in Afghanistan. Charges against the seventh defendant, Habis Al Saoub, were dismissed after he was killed in Pakistan by Pakistani troops on October 3, 2003.

On August 6, 2003, Maher Hawash pled guilty to conspiracy to supply services to the Taliban. On September 18, 2003, brothers Ahmed and Muhammad Bilal pled guilty to federal weapons charges and conspiracy to contribute services to the Taliban. On September 26, 2003, October Martinique Lewis, the ex-wife of Jeffrey Leon Battle, pled guilty to money laundering for the purpose of assisting Battle in willfully supplying services to the Taliban. On October 16, 2003, Battle and Patrice Lumumba Ford pled guilty to seditious conspiracy. Prison sentences for cell members taken into custody ranged from three to 18 years.

October 7, 2003

Sentencing of Raymond Anthony Sandoval

On October 7, 2003, a U.S. District judge in New Mexico sentenced Raymond Anthony Sandoval to 84 months incarceration and to make restitution payment of $3 million for having initiated the June 1998 Oso Complex wildfire near Espanola, New Mexico, and attempting to bomb the Santa Fe, New Mexico, offices of the Forest Guardians environmentalist group on March 19, 1999. On June 25, 2003, Sandoval pled guilty to charges of manufacturing a destructive device, possession of an unregistered firearm, arson on federal land, and willfully injuring property of the United States. Law enforcement officers with the FBI, U.S. Forest Service, and Espanola, New Mexico Police arrested Sandoval on February 14, 2003.

October 28, 2003

Iyman Faris Sentenced for Material Support to al-Qa’ida

On October 28, 2003, a federal court in the Eastern District of Virginia sentenced U.S. citizen Iyman Faris (aka Mohammed Rauf) to 20 years in prison. Faris had been charged with conspiracy and providing material support to al-Qa’ida and pled guilty on May 1, 2003. According to the indictment and plea, Faris conducted casing of a New York City bridge and researched and provided information on U.S. targets to al-Qa’ida.

December 2003

Sentencing of Lackawanna Six Terror Cell Members

In December 2003, Faysal Galab, Shafal Mosed, Yahya Goba, Sahim Alwan, Yasein Taher, and Mukhtar Albakri received federal prison sentences ranging from seven to 10 years after pleading guilty to providing material support or resources to al-Qa’ida. The six individuals, who resided in Lackawanna, New York, traveled to Afghanistan in the summer of 2001 to attend the al-Farooq terrorist training camp near Kandahar. Attendees were present at this camp for a period of up to two months and received terrorism training; several of the men were also present for a speech by Usama Bin Ladin. They were arrested in September of 2002 for providing material support or resources to a designated foreign terrorist organization.

The FBI recorded five terrorist incidents and five terrorism preventions in 2004. Domestic extremists were responsible for each incident. Three of the incidents involved possible associates of the Earth Liberation Front environmental extremist movement, who used incendiary devices against car dealerships, construction sites and housing developments. In a fourth incident, associates of the Animal Liberation Front conducted two attacks against an animal science facility on the campus of Brigham Young University, which resulted in more than $75,000 in damages. Another incident involved a white supremacist affiliated with Aryan Nations who firebombed a synagogue in Oklahoma City, Oklahoma.

In the first terrorism prevention, law enforcement officers in Birmingham, Alabama, arrested two men in possession of multiple firearms, bomb-making literature, components of an improvised explosive device, and literature related to the Waco and Ruby Ridge incidents, as well as photographs of serial bomber Eric Rudolph. The second terrorism prevention involved the same white supremacist arrested in 2004 for firebombing an Oklahoma City synagogue, and for whom further investigation uncovered his intention to commit additional attacks against minorities. The third prevention involved a plot by extremist members of the Montana-based Project 7 Militia to kidnap and assassinate local judges, law enforcement officers, and their family members. The fourth prevention involved a Chicago-area man attempting to sell ammonium nitrate to an individual purportedly associated with a foreign terrorist organization. The fifth prevention involved the arrest of a man in Tennessee who wanted to obtain nuclear or chemical materials to blow up a courthouse.

No deaths or serious injuries resulted from terrorist activity carried out in the United States in 2004.

Among the major international terrorist incidents during 2004, al-Qa’ida conducted a series of terrorist attacks in Saudi Arabia against economic and diplomatic targets through kidnapings, murders, and suicide attacks using small groups of operatives. The attacks resulted in 36 deaths, including the deaths of six Americans, and over two dozen injuries, including those to four Americans. Another major incident involved the coordinated bombing of the train system in Madrid, Spain, by terrorists affiliated with the violent global jihadist movement. A total of 10 bombs detonated during the March 11 morning rush hour in Madrid, killing 191 persons and injuring more the 1,400. Although this incident did not result in any American casualties and is not elsewhere summarized in this report, the Madrid bombing is significant in showing the extension of global jihadist violence outside of predominantly Muslim nations.

January 19, 2004

Arson

Henrico County, Virginia

(One act of Domestic Terrorism)

On January 19, 2004, Henrico County Fire Department officials discovered four Molotov cocktails that had been used to commit arson on a Ford car dealership. One Molotov cocktail scorched a vehicle in the dealership. Investigators on the scene also discovered a BMW on which the letters “XXX” were spray-painted. A business neighboring the dealership had the letters “XELFX” spray-painted on it. Christopher Kyle Salmon and Timothy Ryan Kennedy were convicted of attempted arson. Salmon was sentenced to 24 months in prison, two years of probation, and $500 restitution. Kennedy was sentenced to 25 months in prison, two years of probation, and $500 restitution.

April 1, 2004

Arson

Oklahoma City, Oklahoma

(One act of Domestic Terrorism)

On April 1, 2004, Sean Michael Gillespie used a Molotov cocktail to firebomb the Temple B’nai Israel in Oklahoma City, Oklahoma. The attack caused mostly smoke damage to the synagogue. Gillespie committed the arson as a target of opportunity when he could not locate for a similar attack the address of a person he presumed to be Jewish, whose name he had randomly discovered in a phone book. On April 16, 2004, the FBI arrested Gillespie for the firebombing. A search of Gillespie’s residence and truck revealed two videotapes, a baseball bat, brass knuckles, and a stun gun. One of the videotapes clearly implicates Gillespie in the firebombing of the synagogue. Gillespie had claimed association with the Aryan Nations and stated that he was proud of his actions. On April 26, 2005, Gillespie was convicted on charges related to the possession and use of an explosive device and on August 30, 2005, was sentenced to 39 years in prison.

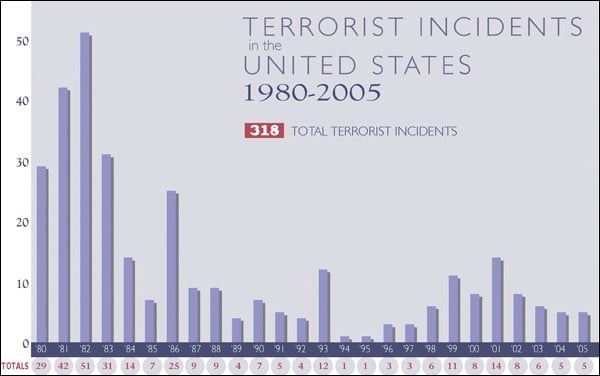

This graphic bar chart showing the terrorist incidents in the United States 1980-2005. 318 incidents showing the number of incidents each year, with 1982 being the highest at 51 incidents and the lowest two years in 1994-1995 each having one incident.

| This table shows the terrorist incidents in the United States 1980-2005 | |

| 1980 | 29 |

| 1981 | 42 |

| 1982 | 51 |

| 1983 | 31 |

| 1984 | 14 |

| 1985 | 7 |

| 1986 | 25 |

| 1987 | 9 |

| 1988 | 9 |

| 1989 | 4 |

| 1990 | 7 |

| 1991 | 5 |

| 1992 | 4 |

| 1993 | 12 |

| 1994 | 1 |

| 1995 | 1 |

| 1996 | 3 |

| 1997 | 3 |

| 1998 | 6 |

| 1999 | 11 |

| 2000 | 8 |

| 2001 | 14 |

| 2002 | 8 |

| 2003 | 6 |

| 2004 | 5 |

| 2005 | 5 |

| Total | 318 terrorist incidents |

April 20, 2004

Vandalism and Arson

Snohomish, Washington

(One act of Domestic Terrorism)

In the early morning of April 20, 2004, two new homes were destroyed and another was damaged by arson, and an improvised incendiary device (IID) was found inside a fourth home at a new housing development in the Lobo Ridge area of Snohomish, Washington. The causes of the arson incidents are believed to be IIDs of the type recovered, consisting of jugs with duct-taped fuses and filled with flammable liquid. Approximately 20 miles away from the arson location, six containers of flammable liquid, duct tape, matches, and fuselike material were found by a contractor. The containers were found at the end of an uninhabited cul-de-sac of another new housing development along with graffiti that read “Consider these 13 as a warning. Walk on the edge. Green equals no burn all others are fair game. Bush is a rapist. ELF.”.

On April 21, 2004, three additional IIDs were found in a new construction subdivision several miles from where the previous day’s incidents had occurred. The devices, which were ignited but failed to completely burn, resulted in no damage to the homes. The devices were similar to those found earlier. No note or claim of responsibility was found at this scene. The discovery of these three devices brought the total number of IIDs to 13, corresponding to the number warned of in the original ELF graffiti.

May-July, 2004

Vandalism and Arson

Provo, Utah

(One act of Domestic Terrorism)

On July 8, 2004, an arson occurred at the Ellsworth Farm animal science facility on the campus of Brigham Young University. The building was also vandalized and the walls spray painted with the phrases “ALF,” “war is on,” “you are the terrorists,” and “this will never end.” Damages from the fire and vandalism were estimated at over $75,000. Two related vandalism incidents attributed to the Animal Liberation Front (ALF) occurred at the same facility in May 2004. Harrison Burrows and Joshua Demmitt confessed to the July arson and May incidents. In January 2005 Burrows and Demmitt were each sentenced to 30 months in federal prison.

December 27, 2004

Attempted Arson

Lincoln, California

(One act of Domestic Terrorism)

On December 27, 2004, four incendiary devices were placed in two homes under construction in Lincoln, California. However, the devices failed to function as intended. The site contained Earth Liberation Front (ELF)-related graffiti on one of the homes as well as the letters “ELF” on the cul-de-sac where the homes were located. Members of the Sacramento Joint Terrorism Task Force arrested Ryan Lewis, Eva Holland, Lili Holland, and Jeremiah Colcleasure in connection with the incident. The four were convicted of arson and Colcleasure, Holland, and Holland were each sentenced to two years in federal prison; Lewis received a six year prison sentence for his role in this incident and for arsons that took place in early 2005.

January 20, 2004

Planned Attacks Using Explosives

Birmingham, Alabama

(Prevention of one act of Domestic Terrorism)

On January 20, 2004, the Birmingham Joint Terrorism Task Force arrested David Nelson Hemphill for possession of pipe bombs and a homemade silencer. Subsequent searches of Hemphill’s person and property revealed a .45-caliber handgun, bomb-making materials, antigovernment and bomb-making literature, and components of an ammonium nitrate fuel oil (ANFO) improvised explosive device. Hemphill admitted that prior to his arrest he had been trying to construct ANFO bombs. Hemphill’s associate, Bruce Stephen Metzler, was also arrested. A search of Metzler’s person and property revealed two .22-caliber handguns, a .233-caliber rifle, a .308-caliber assault rifle, a single- barrel shotgun, a .38-caliber revolver, literature related to the Waco and Ruby Ridge incidents, and photographs of an abortion clinic bombed by serial bomber Eric Rudolph. Also located were two empty 20 mm military ammunition containers, wire end caps, fuses, gunpowder, and a partially constructed silencer. Hemphill and Metzler pled guilty to weapons charges. On January 25, 2005, Hemphill was sentenced in the Southern District of Alabama to 23 months in prison followed by 24 months supervised release. On September 22, 2004, Metzler was sentenced to probation.

|

May-December 2004 Early attacks by al-Qa’ida regional affiliate al-Qa’ida in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP)—such as the May 12, 2003, coordinated bombings of three residential compounds in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia—focused on large mass-casualty events using vehicle-borne improvised explosive devices. After April 2004, AQAP changed tactics to include individual kidnapings, murders, and attacks against economic and diplomatic facilities using small teams of suicide operatives. Attacks by AQAP operatives that used these tactics and involved U.S. citizens or interests during 2004 include:

In response to these incidents, the FBI deployed investigative teams to assist Saudi authorities. Law enforcement actions have resulted in the deaths or capture of many of the perpetrators, including AQAP leader Abd al-Aziz al-Muqrin, who was killed in a shoot-out with Saudi authorities in June 2004.

|

April 16, 2004

Planned Attacks against Minorities

Oklahoma City, Oklahoma

(Prevention of one act of Domestic Terrorism)

As noted in 2004 Terrorist Incidents, the FBI arrested Sean Michael Gillespie on April 16, 2004, for having firebombed the Temple B’nai Israel in Oklahoma City, Oklahoma. The attack against the synagogue in Oklahoma City was likely the first of a series of unspecified attacks Gillespie intended to commit. Following Gillespie’s arrest, a search of his residence revealed a videotape containing surveillance of a Las Vegas synagogue and a statement by Gillespie that he was on a “mission for the white race,” which was to involve a cross-country spree of unspecified terrorist acts. Concern for future attacks was also supported by Gillespie’s admission following his arrest to having previously committed random acts of vandalism and violence against minorities.

May 6, 2004

Convictions of Project 7 Militia Extremists

Flathead County, Montana

(Prevention of one act of Domestic Terrorism)

On May 6, 2004, several extremist members of the Project 7 Militia were arrested following an extensive investigation into the group by FBI, Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, and Firearms, and local police. Investigation had identified leader David Burgert and five other members of the Project 7 Militia as having committed various violations of federal law in furtherance of violent plans targeting law enforcement officers and other government officials. Burgert, along with Tracy Brockway, James Day, John Slater, and Steven Morey, pled guilty to various federal weapons charges, including possession of machine guns and other illegal weapons as well as conspiracy to possess illegal weapons. On November 12, 2004, Burgert received an 87 month prison sentence for his role in the plotting. In early 2005, the four other members who entered guilty pleas received sentences ranging from 18 to 37 months in federal prison. A sixth subject, Larry Chezem, was convicted in a federal trial of conspiracy and was sentenced on September 30, 2005, to 15 months in prison.

August 5, 2004

Planned Attacks against Federal Buildings

Chicago, Illinois

(Prevention of one act of Domestic Terrorism)

On August 5, 2004, the FBI arrested Gale William Nettles in connection with his attempted sale of a half ton of ammonium nitrate to an undercover agent purportedly associated with a foreign terrorist organization. The FBI also had information that Nettles intended to use ammonium nitrate to bomb Chicago’s Dirksen Federal Office Building. Nettles planned to counterfeit U.S. currency in order to earn money to purchase bomb components for his attack. On September 15, 2005, Nettles was found guilty of attempting to bomb the Dirksen Building and awaited sentencing at the end of 2005.

October 25, 2004

Planned Attacks against Federal or State Courthouse

Memphis, Tennessee

(Prevention of one act of Domestic Terrorism)

On October 25, 2004, Demetrius Van Crocker was arrested in Jackson, Tennessee, for attempting to obtain C-4 explosives and Sarin nerve gas from an undercover FBI agent. Van Crocker was planning to use these materials to blow up a federal or state courthouse in furtherance of his hatred toward the U.S. and State of Tennessee governments. Van Crocker’s federal trial on chemical weapons and explosives violations was pending at the end of 2005.

February 9, 2004

Final Sentencings in Portland Terror Cell Case

On February 9, 2004, three men affiliated with a terrorist cell in Portland, Oregon, were given prison sentences. Maher Hawash received a seven-year prison sentence, while two of his co-conspirators, Ahmed and Mohammed Bilal, were sentenced to ten and eight years in prison, respectively. The three men, along with three other suspects, pled guilty in 2003 to conspiracy to provide services to the Taliban and conspiracy to use firearms in a crime of violence. Several of these individuals had planned to travel to Afghanistan to fight alongside the Taliban against U.S. and Coalition forces. Three other Portland cell members were sentenced in 2003.

March Through April 2004

“Virginia Jihad” Members Convicted and Sentenced

On April 9, 2004, Randall T. Royer and Ibrahim Ahmed al-Hamdi were sentenced to 20 years and 15 years in prison, respectively, for their roles in an alleged “Virginia Jihad” terrorist cell, which conducted weapons training in Virginia. On March 4, 2004, Masoud Khan, Seifullah Chapman, and Hammad Abdur-Raheem, three other cell members arrested in the case, were convicted on conspiracy and weapons charges. Two other men, Yong Ki Kwon and Khwarja Mahmood Hasan, pled guilty in the case, and testified that they had attended a training camp associated with the terrorist group Lashkar-e-Tayyiba with the intention of fighting on the side of the Taliban against U.S. forces in Afghanistan. The remaining two members of the group were not convicted. A federal judge acquitted Sabri Benkhala on March 9, 2004, and the case against Caliph Basha Ibn Abdur-Raheem was dismissed.

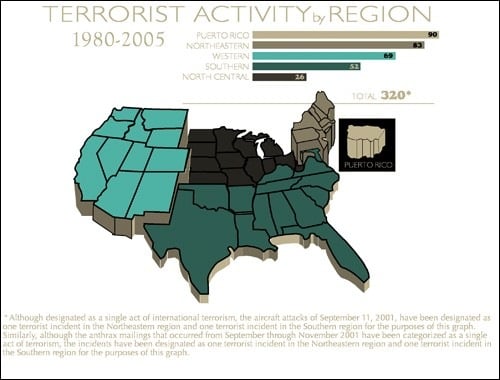

Terrorism Activity by Region 1980 - 2005

Terrorist activity by region 1980-2005. The graphic of map of the USA in 5 regions shows Puerto Rico region with 90 incidents, Northeastern region with 83 incidents. Western regions with 69 incidents. Southern region with 2 incidents. North Central region with 26 incidents. Note: Although designated as a single act of international terrorism, the aircraft attacks of September 11, 2001, have been designated as one terrorist incident in the Northeastern region and one terrorist incident in the southern region for the purposes of this graph. Similarly, although the anthrax mailings that occurred from September through November 2001 have been categorized as a single act of terrorism, the incidents have been designated as one terrorist incident in the Northeastern region and one terrorist incident in the southern region for the purposes of this graph.

April 26, 2004

Sentencing of Symbionese Liberation Army Member

On April 26, 2004, Symbionese Liberation Army (SLA) member James William Kilgore was sentenced to 48 months in prison for several bombings in California in 1975. Kilgore was also sentenced to six months in prison for passport fraud charges. Kilgore was arrested in Cape Town, South Africa, in 2002 and was indicted for multiple murders, possession of an explosives device, and other charges in conjunction with his membership in the SLA, an organization that sought to overthrow the U.S. government in the 1970s.

June 2, 2004

Mohammed Junaid Babar Guilty Plea

On April 10, 2004, the FBI arrested naturalized U.S. citizen Mohammed Junaid Babar in New York City for his suspected role in providing material support to al-Qa’ida that included support for a terrorist plot to blow up pubs, train stations, and restaurants in the United Kingdom. This arrest followed police actions by British authorities, who, in late March 2004, arrested eight British citizens and seized approximately 1,320 pounds of ammonium nitrate from a self-storage warehouse in west London in connection with the same plot. On June 2, 2004, Junaid Babar pled guilty in the Southern District of New York to five counts of conspiring to provide material support to al-Qa’ida. Sentencing for Junaid Babar was pending at the end of 2005.

June 10, 2004

Nuradin M. Abdi Indicted

On June 10, 2004, a federal grand jury indicted Nuradin M. Abdi on terrorism charges. The four-count indictment included charges of conspiracy to provide material support to terrorists; conspiracy to provide material support to al Qa’ida, a designated foreign terrorist organization; fraud and misuse of documents; and fraudulent use of travel documents. Abdi, a Somali national living in the United States, is believed to have misrepresented his reasons for travel on a federal government form, claiming he intended to travel to Germany and Saudi Arabia for religious and family reasons when he actually planned to travel to Ethiopia for terrorism training. Abdi allegedly conspired to blow up a shopping mall in the Columbus, Ohio, area and engaged in explosives instruction in preparation for this plot. Abdi is also accused of obtaining refugee asylum status through false means. The indictment was originally filed under seal and was unsealed on June 14, 2005.

July 26, 2004

The 9/11 Commission Report Published

On July 26, 2004, the National Commission on Terrorist Attacks Upon the United States issued its final report on the September 11, 2001, attack. The report accounted for the circumstances surrounding the attack and provided recommendations for change. The FBI had submitted to the commission the “Report to the National Commission on Terrorist Attacks Upon the United States: The FBI’s Counterterrorism Program Since September 2001” on April 14, 2004. This report covers the FBI’s efforts to improve its counterterrorism capabilities since the attacks of September 11 and supplemented the testimony of several senior FBI officials.

August 19, 2004

Indictment of HAMAS Associates for Criminal Enterprise

On August 19, 2004, the FBI arrested Muhammad Salah, of Chicago, and Abdelhaleem Ashqar, of Washington, D.C., and issued an arrest warrant for Mousa Abu Marzook, a former U.S. resident who currently resides in Damascus, Syria, and is considered to be a fugitive from justice. These arrest actions followed an indictment by a federal grand jury in Chicago that alleged the three participated in a 15-year racketeering conspiracy in the United States and abroad by joining with 20 identified co-conspirators and others in illegally conducting the affairs of the foreign terrorist organization HAMAS. The indictment, which for the first time identifies HAMAS as a criminal enterprise, alleges that Salah, Ashqar, and Marzook provided money and personnel to HAMAS at a time when HAMAS was engaging in terrorist attacks. Although the defendants were not charged with direct participation in violence, these attacks resulted in the deaths of Israeli military personnel and civilians, as well as American and other foreign nationals in Israel and the West Bank. Trial for the defendants was pending at the end of 2005.

September 22, 2004

Nevada Chapter Leader of Aryan Nations Arrested for Sending Threatening Letters

In December 2003, Steven Joseph Holten, the Nevada Chapter leader for Aryan Nations (AN), began a letter-writing campaign announcing the existence of AN in Nevada and condemning the actions of certain federal, media, and Jewish institutions. Many of the letters contained specific threats to the recipients. On September 22, 2004, FBI agents in Reno arrested Holten. On November 29, 2004, Holten pled guilty to mailing threatening communications through interstate commerce. On March 28, 2005, Holten was sentenced to ten months in prison, three years of supervised release, and a mandatory $100 fine.

September 29, 2004

Sentencings in USS Cole Bombing

On September 29, 2004, a Yemeni court sentenced Abd al-Rahim al-Nashiri and Jamal al-Badawi to death for their roles in the October 12, 2000, bombing of the USS Cole in the Port of Aden, Yemen. Four other men were given prison sentences, ranging from five to 10 years, for their roles in the attack. Seventeen American sailors were killed and more than 40 were injured in the October 12, 2000 bombing of the USS Cole, in which two suicide terrorists pulled a small, bomb-laden boat alongside the U.S. destroyer and detonated their explosives. Al-Badawi was also charged with a similar, failed attack against the USS The Sullivans in January 2000.

December 8, 2004

Signing of the Intelligence Reform and Terrorism Prevention Act of 2004

On December 8, 2004, President Bush signed into law the Intelligence Reform and Terrorism Prevention Act of 2004 (IRTPA). In direct response to the recommendations of the 9/11 Commission, IRTPA instituted reforms to the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act and modified material support statutes for prosecuting terrorists. Among its many organizational provisions, IRTPA created the Office of the Director of National Intelligence; established the Director of National Intelligence as the head of the U.S. Intelligence Community; and instituted the joint-agency National Counterterrorism Center as the primary entity for analyzing intelligence pertaining to transnational terrorism.

December 13, 2004

Yemeni Terror Suspects Indicted

On December 13, 2004, a federal grand jury in the Eastern District of New York indicted two Yemeni nationals, Sheik Mohammad Ali Hassan Al-Moayad and Mohammed Mohsen Yahya Zayed, for conspiracy and attempt to provide material support to al-Qa’ida and HAMAS. Al-Moayad allegedly supported mujahideen around the world, and is believed to have provided money and equipment to al-Qa’ida and raised funds through a Brooklyn mosque for terrorism financing.

In 2005, the FBI recorded five terrorist incidents and three terrorism preventions. All of the incidents involved arson or attempted arson. Domestic terrorists associated with the Earth Liberation Front were responsible for three of the incidents, which targeted commercial and residential construction sites. The other two incidents targeted the residences of persons involved with animal research. One of these incidents was claimed by the Animal Liberation Front, and the other is possibly attributable to animal rights extremists as well.

Separate preventions in Houston, Texas, and Pocatello, Idaho, involved individuals who sought to provide material support or resources to al-Qa’ida. A third prevention involved a group that formed in a Los Angeles prison, which adopted a jihadist ideology and was preparing to commit terrorist acts in the United States in furtherance of the violent global jihadist movement.

No deaths or serious injuries resulted from terrorist activity carried out in the United States in 2005.

A major international terrorist incident in 2005 involved the coordinated suicide bombing of the transit system in London, United Kingdom. The attack, carried out by British citizens affiliated with the violent global jihadist movement, resulted in 52 deaths and approximately 700 injuries. One American died in the attack and four others were injured.

January-February 2005

Arson and Attempted Arson

Auburn and Sutter Creek, California

(One act of Domestic Terrorism)

On January 12, 2005, five intact incendiary devices were discovered at a commercial construction site in Auburn, California. On January 21, 2005, a letter was sent to four newspapers claiming responsibility for the attempted arson by the Earth Liberation Front (ELF).

On February 7, 2005, an arson was reported at an apartment complex in Sutter Creek, California. Fire officials discovered seven partially burned incendiary devices placed in five buildings of the apartment complex. Graffiti found at the site included “ELF” and “We Will Win” in red paint. Sprinkler systems installed in the buildings extinguished six of the seven devices and first responders extinguished the seventh. Damage was estimated at $50,000.

Ryan Daniel Lewis was convicted of arson and attempted arson involving these collective incidents as well as a December 27, 2004, incident in Lincoln, California. On March 17, 2005, Lewis was sentenced to a 72-month prison term followed by three years of supervised release.

|

July 7, 2005 On July 7, 2005, a series of coordinated suicide bomb blasts struck London’s transport system during morning rush hour. Beginning at 8:50 a.m. three bombs exploded within 50 seconds of each other on three London Underground trains, and a fourth bomb exploded on a bus nearly an hour later at 9:47 a.m. in London’s Tavistock Square. Fifty-two people were killed and approximately 700 injured in the bombing. Among the casualties were one American killed and four wounded. The four suicide bombers were British citizens; three had been born in the United Kingdom, and the fourth had been born in Jamaica. The British citizenship of the bombers and the lack of strong ties between them and an international terrorist group illustrate the potential threat of “homegrown” terrorists as perpetrators of future attacks. |

April 13, 2005

Arson

Sammamish, Washington

(One act of Domestic Terrorism)

In the early morning of April 13, 2005, arson occurred at a nearly completed residence under construction in Sammamish, Washington, and an intact improvised incendiary device (IID) was discovered in a second residence under construction nearby. The IID in the first residence was located in the garage, which was destroyed by the fire. The second IID—a plastic, two-liter bottle filled with fuel and using an improvised igniter—had been placed under debris in the kitchen nook. The device had been activated but did not fully ignite. In addition a bedsheet with the wording, “Where are all the trees? Burn rapist burn. ELF,” had been placed outside the second residence.

July 7, 2005

Attempted Arson

Los Angeles, California

(One act of Domestic Terrorism)

In the early morning of July 7, 2005, fire officials responded to a vehicle fire in the driveway of a private residence in Los Angeles, California. In extinguishing the fire, authorities recovered a partially melted, plastic gasoline container from behind the vehicle’s left front wheel. The car belonged to a representative for the Ani-mal Care Technicians Union, which represents employees for the Los Angeles Animal Services (LAAS). LAAS and its affiliates have been targeted by local animal rights extremists, and the LAAS union representative had been placed on a “targets” list of individuals profiled by extremists for “direct actions.” The incident remains under investigation.

September 16, 2005

Attempted Arson

Los Angeles, California

(One act of Domestic Terrorism)

On September 16, 2005, fire officials responded to a fire at the high-rise condominium home of the director of Los Angeles Animal Services, after residents observed smoke coming from a recyclables/janitorial closet. First responders recovered an improvised incendiary device consisting of a four-inch-long tube labeled “TOXIC” and using a cigarette as a fuse. The device, which had been placed next to a stack of newspapers in the recycling/janitorial closet, had malfunctioned and only scorched the concrete floor of the closet. The Animal Liberation Front claimed responsibility for this incident.

November 20, 2005

Arson

Hagerstown, Maryland

(One act of Domestic Terrorism)

In the early morning of November 20, 2005, five townhomes under construction were set on fire at the Hagers Crossing Development in Hagerstown, Maryland. Fire officials investigating the scene determined that kerosene was used as the accelerant in the arson. The blaze damaged or destroyed five units in two buildings. The Earth Liberation Front claimed responsibility for the fire.

|